Đại Việt

This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (April 2023) |

Đại Cồ Việt (968–1054) Đại Việt (1054–1804) Đại Cồ Việt Quốc (大瞿越國) Đại Việt Quốc (大越國) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 968–1400 1428–1804 | |||||||||

| Religion | Buddhism (State religion from 968 to 1400) Confucianism Taoism Đạo Lương Hinduism Islam Catholicism | ||||||||

| Government | Absolute monarchy (968–1533, 1788–1804) feudal military dictatorship (1533–1788) | ||||||||

| Emperor | |||||||||

• 968–980 (first) | Đinh Bộ Lĩnh | ||||||||

• 1802–1804 (last) | Gia Long | ||||||||

| Military dictators | |||||||||

• 1533–1545 (first) | Nguyễn Huệ | ||||||||

| Historical era | Việt Nam | 1804 | |||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• 1200 | 1,200,000[4] | ||||||||

• 1400 | 1,600,000[5] | ||||||||

• 1539 | 5,625,000[5] | ||||||||

| Currency | Vietnamese văn, banknote | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

Đại Việt (大越, IPA: [ɗâjˀ vìət]; literally Great Việt), often known as Annam (Vietnamese: An Nam, chữ Hán: 安南), was a monarchy in eastern Mainland Southeast Asia from the 10th century AD to the early 19th century, centered around the region of present-day Hanoi, Northern Vietnam. Its early name, Đại Cồ Việt,[note 1] was established in 968 by Vietnamese ruler Đinh Bộ Lĩnh after he ended the Anarchy of the 12 Warlords, until the beginning of the reign of Lý Thánh Tông (r. 1054–1072), the third emperor of the Lý dynasty. Đại Việt lasted until the reign of Gia Long (r. 1802–1820), the first emperor of the Nguyễn dynasty, when the name was changed to Việt Nam.[6][7]

Đại Việt's history is divided into the rule of eight dynasties:

Early Đại Việt emerged in the 960s as a hereditary monarchy with

Etymology

Việt

The term "

From the 3rd century BC on, the term was used for the non-

When the word Yue (

Đại Cồ Việt

Đại Cồ Việt was the name chosen by Đinh Bộ Lĩnh for his realm when he declared himself emperor in 966.[20] It is probably derived from the vernacular Cự Việt ("Great Việt") or Kẻ Việt ("Việt Region") with the Sino-Vietnamese Đại ("Great") added as a prefix. The name appeared in the 15th century text Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư but not the earlier 13th or 14th century text Đại Việt sử lược. According to Momoki Shiro, Đại Cồ Việt may have been the result of a mistake in the records or invented while compiling old records.[21]

Đại Việt

When

History

Origins

For a thousand years, the area of what is now

Ancient Northern Vietnam and particularly the

Official Vietnamese history textbooks usually assume that the people of Northern Vietnam during Chinese rules were Việt/Yue.

The Li Lao culture flourished from approximately 200 to 750 AD in present-day

The important effects of ten centuries of Chinese rules over Northern Vietnam arguably in terms of complex cultural and linguistics are still clear observable. Some native languages of the regions for a long time had employed Sinitic script and Sinitic-derived writing systems to represent their languages, such as

James Chamberlain believes that the traditional

However, archaeogenetics demonstrate that before the

National historiography

Study of Northern Vietnam and the

No evidence of "ethnic Vietnamese" resembling what would be considered the modern Vietnamese exists during the Han-Tang period.

Beside anachronisms, Vietnamese nationalist scholarship also inserted a Vietnamese resistance myth into history by labeling any rebellious local group in Northern Vietnam during the Han-Tang period as collectively "Vietnamese" who 'were in constant struggles against the Chinese yokes,'[54] in contrast to "corrupt invading Chinese colonizers", generic modern nationalities and ethnicities.[53] The context was heavily entangled with modern perceptions about Vietnam during decolonization and the Cold War.[50][55] Historians such as Catherine Churchman have criticized attempts of characterizing the past through the lens of modern national boundaries and projecting a "wish for the restoration of long-lost national independence" onto localized dynasties.[26]

Founding

Prior to independence in the late 9th century, the area that became Đại Việt in northern Vietnam was ruled by the

A regional regime led by the Khuc family formed on the Red River Delta in the early 10th century. From 907 to 917,

After defeating the Southern Han invasion, Ngô Quyền proclaimed proclaimed himself king over the Principality in 939 and established a new dynasty centered in the old

Đại Cồ Việt (968-1054)

A new leader of prowess named

Queen

After Lê Hoàn died in 1005, civil war broke out between crown princes

Flourishing period: Đại Việt under the Lý and Trần (1054-1400)

Lý dynasty

Emperor

Lý Thái Tổ's son and grandson Lý Thái Tông (r. 1028–1053) and Lý Thánh Tông (r. 1054–1071) continued to strengthen the Viet state. Starting during the reign of Lê Hoàn, the Việt expansion extended Việt territories from the Red River Delta in all directions. The Vietnamese destroyed the Cham northern capital Inprapura in 982, raided and plundered Southern Chinese port cities in 995, 1028, 1036, 1059, and 1060;[77] subdued the Nùng people in 1039; raided Laos in 1045; invaded Champa and pillaged Cham cities in 1044 and 1069,[78] and subjugated three northern Cham provinces of Địa Lý, Ma Linh, and Bố Chính.[79] Contact between the Song dynasty of China and the Việt state increased through raids and tributary mission, which resulted in Chinese cultural influences on Vietnamese culture,[80] the first civil examination based on the Chinese model was staged in 1075, Chinese script was declared the official script of the court in 1174,[1] and the emergence of Vietnamese demotic script (Chữ Nôm) occurred in the 12th century.[81]

In 1054 Lý Thánh Tông changed his kingdom's name to Đại Việt and declared himself an emperor.

Lý Thần Tông was crowned under the supervision of

By the 1190s, more outsider clans were able to penetrate and infiltrate the royal family, weakening further the Lý authority. Three powerful aristocratic families–Đoàn, Nguyễn, and Trần (descendants of Trần Emperors, a Chinese emigre from

Rise of Trần dynasty and Mongol invasions

The young Trần Thái Tông centralized the monarchy, organized the civil examination on the Chinese model, built Royal Academy and Confucian Temple, constructed and repaired the delta dikes during his reign.

Trần Thái Tông's successors Trần Thánh Tông (r. 1258–1278) and Trần Nhân Tông (r. 1278–1293) continued to send tribute to the new Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. In 1283, Yuan emperor Kublai Khan launched the invasion of Champa. In early 1285 he commissioned prince Toghon to led the second invasion of Đại Việt to punish the Vietnamese Emperor Trần Nhân Tông for not helping the Yuan campaign in Champa and refusing to send tribute. Kublai also appointed Trần Ích Tắc, a Trần prince dissent as the puppet Emperor of Đại Việt.[101] Yuan forces though initially captured Thăng Long, however, were defeated by Cham–Vietnamese alliance in June.[102] In 1288 they decided to launch the third and also the largest invasion of Đại Việt but were repelled. Prince Trần Hưng Đạo ended the Mongol yokes through a decisive naval victory in the battle of Bạch Đằng River in April 1288.[103][104] Đại Việt continued to flourish under the reigns of Trẩn Nhân Tông and Trần Anh Tông (r. 1293–1314).[105]

Crisis and Champa invasions

By the 14th century, Đại Việt kingdom began experiencing a long decline. The transitional decade (1326–36) from the end of the

Took advantage, Champa Empire under Po Binasuor (Chế Bồng Nga) invaded Đại Việt and ransacked Thăng Long in 1371. Six years later, the Đại Việt army suffered a great defeat at Battle of Vijaya, and Trần Duệ Tông (r. 1373–1377) was killed. The Chams then continued to advance north, besieging, pillaging, and looting Hanoi four times, from 1378 to 1383.[111] War with Champa ended in 1390 after the Cham king Che Bong Nga was killed during his northward offensive by Vietnamese forces led by prince Trần Khát Chân, who used firearms in battle.[112]

Hồ dynasty (1400-1407)

Hồ Quý Ly (1336–1407)-the minister of the Trần court who has desperately fought off the Cham invasions, now became the most powerful figure in the kingdom. He conducted a series of reforms, including replacing copper coins with banknotes, despite the kingdom still recovering after the devastating war.[113] Time by time, he slowly eliminated the Trần dynasty and aristocracy.[114] In 1400 he deposed the last Trần Emperor and became ruler of Đại Việt.[115] Hồ Quý Ly became emperor, moved the capital to Tây Đô and briefly changed the kingdom's name to Đại Ngu (Great Joy/Peace) (大虞).[116] In 1401 he stepped down and established his second son Hồ Hán Thương (r. 1401–1407) who had Trần blood as king.[115]

Ming invasion and occupation (1407-1427)

In 1406,

The short-lived Ming colonial rule had traumatic impacts on the kingdom and the Vietnamese. In pursuit of their mission civilisatrice (

Revival of Đại Việt: the Primal Lê dynasty (1428-1527)

Lam Sơn uprising

Through his proclamation, Lê Lợi called upon educated men of ability to come forward to serve the new monarchy.[123] The old Buddhist aristocrats were stripped during the Ming occupation and gave rise to the new emerging literati class. For the first time, a centralized authority based on proper laws was instituted. Literary examination now became crucial for the Việt state, scholars like Nguyễn Trãi played a large role in the court.

Lê Lợi shifted his main affair focus to the Tai people and the Laotian Lan Xang kingdom in the west, due to their betrayal and becoming allies with the Ming during his rebellion in the 1420s. In 1431 and 1433, the Việt launched several campaigns on various Tai polities, subdued them, and incorporated the northwest region into Đại Việt.

Rule of Lê Lợi

Lê Lợi died in 1433. He chose the younger prince Lê Nguyên Long (Lê Thái Tông, r. 1433–1442) as heir instead of the eldest Lê Tư Tề. Later Lê Tư Tề was expelled from the royal family and degraded status to a commoner.[124] Lê Thái Tông was only ten years old when he was crowned in 1433. Lê Lợi's former comrades now fought politically with each other to control the court. Lê Sát used his power as the young emperor's regent to purge opposition factions. When Lê Thái Tông found out about Le Sat's abuses of power, he allied with Lê Sát's rival, Trịnh Khả. In 1437, Lê Sát was arrested and given a death sentence.[125]

In 1439 Lê Thái Tông launched a campaign against rebelling Tai vassals in the west and Chinese settlers in Đại Việt. He ordered the Chinese to cut their hair short and wear clothes of the Kinh people.[126] One of his sisters raised in China was forced to commit suicide, being accused of endless conspiracies. Later he had four princes: The eldest son Lê Nghi Dân, the second Lê Khắc Xương, the third Lê Bang Cơ, and the youngest Lê Hạo. In 1442 the emperor died in suspicion after a visit to Nguyễn Trãi's family. Nguyễn Trãi and his clan, relatives were innocently condemned to death.

One-year-old Lê Bang Cơ (Lê Nhân Tông, r. 1442–1459) assumed the throne a few days after his father's death. The emperor was too young and most political power of the court fell Lê Lợi's former comrades Trịnh Khả and Lê Thụ, who allied with the queen mother Nguyễn Thị Anh. During the dry season of 1445–1446, Trịnh Khả, Lê Thụ, and Trịnh Khắc Phục attacked Champa and took Vijaya, where the king of Champa Maha Vijaya (r. 1441–1446) was captured. Trịnh Khả installed Maha Kali (r. 1446–1449) as a puppet king, however, three years later Kali's elder brother murdered him and became king. Relations between the two kingdoms downfall into hostility.[127] In 1451, amidst chaotic political struggles, Queen Nguyễn Thị Anh ordered Trịnh Khả to be executed for an accusation of conspiracy against the royal throne. Only two of Lê Lợi's former comrades, Nguyễn Xí and Đinh Liệt were still alive.[128]

During a night in late 1459, Prince Lê Nghi Dân and followers stormed into the palace, stabbed his half-brother and the mother. Four days later he was proclaimed as emperor. Nghi Dân ruled the kingdom for 8 months, then the two former-Nguyễn Xí and Đinh Liệt carried a coup against him. Two days after Nghi Dân's death, the youngest prince Lê Hạo was crowned, known as Emperor Lê Thánh Tông the Overflowing Virtue[129] (r. 1460–1479).[130]

Lê Thánh Tông's reforms and expansions

In the 1460s, Lê Thánh Tông carried out a series of reforms, from centralizing government, built the first extensive bureaucracy and strong fiscal system, institutionalizing education, trade, and laws. He greatly reduced the power of the traditional Buddhist aristocracy with a scholar-literati class, ushered a brief golden age. Classical scholarly, literature (in nom script), science, music, and culture flourished. Hanoi emerged as the centre of learning of Southeast Asia in the 15th century. Lê Thánh Tông's reforms helped heightened the power of the king and the bureaucratic system, allowing him to mobilize a more massive army and resources that overawed the local nobility and capable to expand the Việt territories.[131]

To expand the kingdom, Lê Thánh Tông launched

Decline and civil war

In the next few decades after Lê Thánh Tông's death in 1497, Đại Việt once again fell to civil unrest. Agricultural failures, rapid population growth, corruption, and factionalism all compounded to stress the kingdom, leading to a rapid decline. Eight weak Lê kings briefly held power. During the reign Lê Uy Mục–known as the "devil king" (r. 1505–1509), bloody fighting ignited between the two rival Thanh Hoá families in the cadet branch, the Trịnh and the Nguyễn on behalf of the ruling dynasty.[135] Lê Tương Dực (r. 1509–1514) tried to restore stability, but chaotic political struggles and rebellions returned years later. In 1516 a Buddhist-peasant rebellion led by Trần Cảo stormed the capital, killed the emperor, plundered, and destroyed the royal palace along with its library.[136] The Trịnh and Nguyễn clans briefly ceased hostility for a short time, suppressed Trần Cảo, and installed a young prince as Lê Chiêu Tông (r. 1517–1522), then they quickly turned against each other and forced the king to flee.[137]

Mạc dynasty (1527-1593)

The chaos prompted

The Lê (assisted by Nguyễn Kim) and the Mạc loyalists fought on behalf of reclaiming the legitimate Vietnamese crown. When Nguyễn Kim died in 1545, the power of the Lê dynasty swiftly fell into the dictate of the lord Trịnh Kiểm of the Trịnh family. One of Nguyễn Kim's sons, Nguyễn Hoàng, was appointed as ruler of the southern part of the kingdom, thus began the Nguyễn family rule over Đàng Trong.[140]

Revival Lê dynasty: Trịnh control and Trịnh-Nguyễn contention (1593-1789)

The Lê-Trịnh loyalists expelled the Mạc from Hanoi in 1592, forcing them to flee into the mountainous hinterland, where their reign lasted until 1677.[141]

The Trịnh-controlled northern Đại Việt was known as Đàng Ngoài (Outer Realm), while the Nguyễn-controlled south became Đàng Trong (Inner Realm). They fought a fifty-year civil war (1627–1673), which ended inconclusively and the two lords signed a peace treaty. This stable division would last until 1771 when three Tây Sơn brothers Nguyễn Nhạc, Nguyễn Huệ and Nguyễn Lữ led a peasant revolution that would overrun and topple the Nguyễn, the Trịnh lords, and the Le dynasty. In 1789, the Tây Sơn defeated a Qing intervention that sought to restore the Lê dynasty.

Tây Sơn wars and Nguyễn dynasty (1789-1804)

Nguyễn Nhạc established a monarchy in 1778 (Thái Đức), followed by his brother Nguyễn Huệ (Emperor Quang Trung, r. 1789–1792) and nephew

Political structure

Pre-1200s

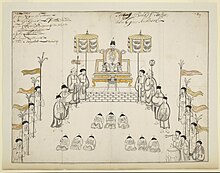

In the early Đại Việt period (pre-1200), the Viet monarchy existed as a form of what historians describe as a "charter state"

Trần-Hồ period

During the 13th and 14th century as the Trần dynasty ruled the kingdom, the Trần first move was preventing matrilineality clans to take over the royal family, by adopting the king–retired king relation, which the emperor usually abdicated in favor of his eldest son while retaining power behind the scenes, and practicing consanguine marriage. To prevent maternal families’ influences, Trần kings took only queens from their dynastic lineage. The state had been more centralized, taxes and bureaucracy appeared, chronicles were written down. Most power is concentrated in the hands of the emperor and the royal families. In the lowland, the Trần removed all non-Trần, autonomous aristocratic clans from the power, appointed Trần princes to rule these lands, tightened up relations between the state and locals. Working in Trần princely lands were serfs-poor peasants that own no land and slaves. Large hydraulic projects that mobilized more labors such as Red River Delta’s dyke system were constructed-one that maintained and increased its particularly wet-rice-based agricultural economy and its population by diverting rivers to aid in irrigation.[149] Confucianism was ensured by the Trần monarchs as the second belief, gave rise to the literati class, which later became rivals to the established Buddhist clergies.

The Việt monarchy during this period faced a series of massive Yuan and Cham invasions, political unrest, famines, disasters, and diseases, and was led to a nearly collapse in the late 1300s. Hồ Quý Ly as the minister had tried to fix the troubles by eliminating the Trần aristocrats, limiting monks, and promote Chinese classic learning, however, resulted in political catastrophe.[150]

Early modern period

From Lê Thánh Tông's 1463 reforms onward, the Vietnamese state's structure was modeled after the Ming dynasty of China. He established six Ministries and six Courts. The government had been centralized. By 1471, Đại Việt was divided into 12 provinces and one capital city (Thăng Long), each governed by a provincial government consisted of military commanders, civil administrators, and judicial officers.[151] Lê Thánh Tông employed 5,300 officials into the bureaucracy. A new legal code called the Lê Code was published in 1462 and was practiced until 1803.[152]

As a Confucian king, Le Thanh Tong generally disliked cosmopolitanism and foreign trade. He banned slavery, which had been popular during previous centuries, limited trade and commercial. During his reign, power was based on institutional obligations that enforced loyalty to court and merits, rather a religious relationship between aristocracy and the royal court. Self-sufficient agriculture and state-monopolized crafting were encouraged.[153]

The social hierarchy of 15th century Đại Việt comprised:[154]

Non-royal nobility:

After the death of Le Thanh Tong in 1497, the social-political orders he had built gradually fell apart as Đại Việt was entering its chaotic disintegration period under the reigns of his weak successors.[155] Social upheavals, ecological crisis, corruption, irreparable failing system, political rivalry, rebellions pushed the kingdom to a climatic burst of civil war between rival clans.[156] The last Le king was overthrown by general Mạc Đăng Dung in 1527, who promised to restore "Le Thanh Tong's golden era and stability." For the next six decades, from 1533 to 1592, the raging civil war between the Le loyalists and the Mạc had ruined much of the polity. The Trịnh and Nguyễn clans both assisted the Le loyalists in their struggle against the Mạc.

After the Le-Mac war ended in 1592 with the Mạc ousted from the Red River Delta, the two clans of Trịnh and Nguyễn who revived the Le dynasty emerged as the strongest powers, and resumed their own infighting, from 1627 to 1672. The northern Trịnh clan had installed themselves as regency for the Le dynasty by 1545, but in reality, they hold most power of the royal court and de facto rulers of the northern half of Đại Việt, and began using the title Chúa (lord), which is outside of the classical hierarchy of nobility.[157] The Le king was reduced to a figurehead, he ruled in earnest, while the Trịnh lord had total power to select and enthrone or remove any king the lord favors. The southern Nguyễn leader also began to proclaim as Chúa lord in 1558. Initially, they were considered subjects of the Le court, which was controlled by the Trịnh lord. But later, by the early 1600s, they ruled southern Đại Việt like an independent kingdom and became the main rival to the Trịnh domain. Le Thanh Tong's legacy such as his 1463 Code and bureaucratic institutions, was revived in the north and somehow continued to persist and lasted until French Indochina period.[158]

Before and after the war, the two Thanh Hoá clans divided the kingdom into two simultaneously coexist but rival regimes: the northern Đàng Ngoài or Tonkin ruled by the Trịnh family while the southern Đàng Trong or Cochinchina ruled by the Nguyễn family; their natural border is the city of Đồng Hới (18th parallel north).[159] Each polity had its own independent court, however, the Nguyễn lord still sought to subordinate himself with the Lê dynasty, which also stayed under Trịnh supervision,[160] trying to pretend an imaginary unity. Paying homage and respect to the Le king remained a source of both lords' legitimacy and of adherence to the idea of a unified Vietnamese state, even if such a thing no longer existed or was loosely emptied.

The Tay Son rebellion of the late 18th century Đại Việt was an extraordinary movement of Đại Việt's chaotic period when the three Tay Son brothers divided the kingdom into three subordinating but independently realms ruled by them who all declared kings: Nguyen Hue controlled the north, Nguyen Nhac controlled the central, and Nguyen Lu controlled the Mekong Delta.

Economy

Fan Chengda (1126–1193), a Chinese statesman and geographer, wrote an account in 1176 that described the medieval Vietnamese economy:

...Local [Annamite] products include such things as gold and silver, bronze, cinnabar, pearls, cowry [shells], rhinoceros [horn], elephant, kingfisher feathers, giant clams, and various aromatics, as well as salt, lacquer, and kapok...[161]

...Travelers to the Southern Counties [Southern China] entice people there to serve [in Annam] as female slaves and male bearers. But when they reach the [Man] counties and settlements, they are tied up and sold off. One slave can fetch two taels of gold. The counties and settlements then turn around and sell them in Jiaozhi [Hanoi], where they fetch three taels of gold. Each year no fewer than 100,000 people [are sold off as slaves]. For those with skills, the price in gold doubles...[162]

Unlike southern neighbor

Đại Việt's only single port located at the mouth of the Red River–a town called Van Don

Compared to a more well-known Champa, Đại Việt was little known to the faraway world until the 16th century with the arrival of Spanish and Portuguese explorers. Medieval sources such as Ibn al-Nadim's The Book Catalogue (c. 988 AD) mention that the king of Luqin or Lukin (Đại Việt) invaded the state of Sanf (Champa) in 982.[166] Đại Việt was included in the Arab geographer Muhammad al-Idrisi's world atlas–the Tabula Rogeriana. In the early 1300s, Đại Việt was briefly chronicled by Persian historian Rashid al-Din in his Ilkhanid annals as Kafje-Guh, which was the rendition of a Mongol/Chinese toponym for Đại Việt, Jiaozhiquo.[167]

Art and religion

Vietnamese Buddhism gained an apex during the medieval period. The king, the court, and society were deeply Buddhist. According to

The Buddhist sangha sponsored by the royals, owned the majority of farmlands and the kingdom's wealth. A stele erected in 1209 records that the royal family had donated 126 acres of land to a pagoda.[178] A Vietnamese Buddhist temple often consists of a temple built by timber, and pagoda/stupas made of bricks or granite rocks. Việt Buddhist art notably shares similarities with Cham art, especially at sculptures.[179] The dragon bodhi leaf sculpture symbolizes the emperor, while the phoenix bodhi leaf stands for the queen.[180] Buddhism shaped the society and the laws during the Ly dynasty Đại Việt. Princes and royals were raised in Buddhist monasteries and monkhood. A Buddhist Arhat Assembly was instituted to legislate monastic and temple affairs generated relatively tolerant laws.[181]

Vietnamese Buddhism declined in the 15th century due to the Ming Chinese Neo-Confucianism anti-Buddhist agenda and later Le monarchs downplaying of Buddhism, but was revived in the 16th–18th century when the royal family's efforts to restore Buddhism's role in society, which resulted in today Vietnam's majority Buddhist country.

- Vietnamese Buddhist temples

-

Vĩnh Phúc, built around the year 1200.

-

Phổ Minh Temple, built in ca. 1262.[185]

-

-

A 14th-century pagoda in the jungles of Quảng Ninh.

-

Bảo Nghiêm Pagoda, in Bút Tháp Temple, built c. 1647.[187]

-

The pagoda of Trấn Quốc Pagoda, c. 1615.[188]

-

Thiên Mụ Temple, c. 1590.

-

Dâu Temple, c. 1647.[189]

Maps

-

Đại Việt during Đinh dynasty (blue, top right)

-

Đại Việt during Lý dynasty in 1100

-

Đại Việt during Trần dynasty (1225–1400) and Hồ dynasty (1400–1407)

-

Đại Việt during the reign of Lê Thánh Tông c. 1480

-

Đại Việt c. 1540

-

Đại Việt (Annam) with Mạc (green) and Lê-Nguyễn-Trịnh (blue) c. 1570

-

Đại Việt c. 1650

-

Đại Việt during Tây Sơn dynasty

Timeline (dynasties)

Started in 968 and ended in 1804.

Ming domination |

French Indochina | |||||||||||||||||||

Chinese domination |

Ngô | Đinh | Early Lê | Lý | Trần | Hồ | Later Trần | Lê | Mạc | Revival Lê | Tây Sơn | Nguyễn | Modern time | |||||||

| Trịnh lords | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Nguyễn lords | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 939 | 1009 | 1225 | 1400 | 1427 | 1527 | 1592 | 1788 | 1858 | 1945 | |||||||||||

| History of Vietnam (by names of Vietnam) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

See also

- Champa

- List of monarchs of Việt Nam

References

Citations

- ^ a b Li (2020), p. 102.

- ^ Hall (1981), p. 203.

- ^ Lieberman (2003), pp. 2, 398–399, 455.

- ^ Kiernan (2019), p. 168.

- ^ a b Li (2018), p. 171.

- ^ Lieberman (2003), p. 345.

- ^ Hall (1981), p. 456.

- ISBN 978-0-295-80022-6.

- ^ .

- ^ doi:10.7152/bippa.v15i0.11537 (inactive 2024-03-16). Archived from the original on 2014-02-28.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of March 2024 (link - ^ Theobald, Ulrich (2018) "Shang Dynasty - Political History" Archived 2022-05-20 at the Wayback Machine in ChinaKnowledge.de - An Encyclopaedia on Chinese History, Literature and Art. quote: "Enemies of the Shang state were called fang 方 "regions", like the Tufang 土方, which roamed the northern region of Shanxi, the Guifang 鬼方 and Gongfang 𢀛方 in the northwest, the Qiangfang 羌方, Suifang 繐方, Yuefang 戉方, Xuanfang 亘方 and Zhoufang 周方 in the west, as well as the Yifang 夷方 and Renfang 人方 in the southeast."

- ^ Wan, Xiang (2013) "A Reevaluation of Early Chinese Script: The Case of Yuè 戉 and Its Cultural Connotations: Speech at The First Annual Conference of Society for the Study of Early China" Archived 2022-07-19 at the Wayback Machine Slide 36 of 70

- ISBN 978-0-8047-3354-0. "For the most part, there are no rulers to the south of the Yang and Han Rivers, in the confederation of the Hundred Yue tribes."

- ^ a b c Churchman (2010), p. 28.

- ^ Churchman (2010), p. 29.

- ^ Churchman (2010), p. 30.

- ^ Golzio, Karl-Heinz (2004), Inscriptions of Campā based on the editions and translations of Abel Bergaigne, Étienne Aymonier, Louis Finot, Édouard Huber and other French scholars and of the work of R. C. Majumdar. Newly presented, with minor corrections of texts and translations, together with calculations of given dates, Shaker Verlag, pp. 163–164

- from the original on 2021-12-10. Retrieved 2022-04-04.

- ^ Churchman (2010), p. 33.

- ^ Taylor 1983, p. 222.

- ^ a b Momoki Shiro, The Vietnamese empire and its expansion circa 980–1840 in Asian Expansions: The historical experiences of polity expansion in Asia, edited by Geoff Wade, p. 158

- ^ Taylor 2013, p. 73.

- ^ Kiernan 2019, p. 4.

- ^ a b Churchman (2010), p. 26.

- ^ Churchman (2010), pp. 25–27.

- ^ a b Churchman (2016), p. 26.

- ^ Churchman (2010), p. 31.

- ^ Churchman (2016), p. 103.

- ^ Churchman (2016), p. 72.

- ^ Churchman (2016), p. 69.

- ^ Churchman (2016), p. 204.

- ^ Churchman (2016), pp. 133–137.

- ^ Churchman (2016), pp. 174–183.

- ISBN 978-3-11055-814-2.

- ^ Chamberlain (2000), p. 122.

- ^ Jiu Tangshu, vol. 8 "Xuanzong A" Archived 2021-08-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Jiu Tangshu vol. 188 Archived 2021-08-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Chamberlain (2000), p. 119.

- PMID 29773666.

- ^ Corny, Julien, et al. 2017. "Dental phenotypic shape variation supports a multiple dispersal model for anatomically modern humans in Southeast Asia." Journal of Human Evolution 112 (2017):41-56. cited in Alves, Mark (2019-05-10). "Data from Multiple Disciplines Connecting Vietic with the Dong Son Culture". Conference: "Contact Zones and Colonialism in Southeast Asia and China's South (~221 BCE - 1700 CE)"At: Pennsylvania State University

- ^ McColl et al. 2018. "Ancient Genomics Reveals Four Prehistoric Migration Waves into Southeast Asia". Preprint. Published in Science. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/278374v1 Archived 2023-03-26 at the Wayback Machine cited in Alves, Mark (2019-05-10). "Data from Multiple Disciplines Connecting Vietic with the Dong Son Culture". Conference: "Contact Zones and Colonialism in Southeast Asia and China's South (~221 BCE - 1700 CE)"At: Pennsylvania State University

- ^ Alves, Mark (2019-05-10). "Data from Multiple Disciplines Connecting Vietic with the Dong Son Culture" Archived 2022-01-29 at the Wayback Machine. Conference: "Contact Zones and Colonialism in Southeast Asia and China's South (~221 BCE - 1700 CE)"At: Pennsylvania State University

- ^ Churchman, (2010). "Before Chinese and Vietnamese in the Red River Plain: The Han–Tang Period" Archived 2021-03-09 at the Wayback Machine. Chinese Southern Diaspora Studies. 4. p. 36

- ^ Kiernan (2019), p. 110.

- ^ Kiernan (2019), pp. 124–125.

- ^ Phan, John. 2013. Lacquered Words: the Evolution of Vietnamese under Sinitic Influences from the 1st Century BCE to the 17th Century CE. Ph.D. dissertation: Cornell University. p. 430-434

- ^ Churchman (2016), p. 23.

- ^ Churchman (2016), p. 27.

- ^ Churchman (2016), pp. 27–28.

- ^ a b c Churchman (2016), p. 25.

- ^ Churchman (2016), p. 46.

- ^ Kiernan (2019), p. 133.

- ^ a b Churchman (2016), p. 28.

- ^ Churchman (2016), p. 68.

- ^ Churchman (2016), p. 29.

- ^ Kiernan (2019), pp. 120–124; Schafer (1967).

- ^ Taylor (2013), pp. 43–44.

- ^ Taylor (2013), p. 45.

- ^ Taylor (2013), p. 46.

- ^ Kiernan (2019), p. 127.

- ^ Kiernan (2019), p. 139.

- ^ Kiernan (2019), p. 140.

- ^ Taylor (2013), p. 47.

- ^ Trần, Trọng Dương. (2009) "Investigation on 'Đại Cồ Việt' (Việt nation - Buddhist nation)" originally published in Hán Nôm, 2 (93) p. 53–75. online version Archived 2021-08-02 at the Wayback Machine (in Vietnamese)

- ^ Pozner P.V. (1994) История Вьетнама эпохи древности и раннего средневековья до Х века н.э. Издательство Наука, Москва. p. 98, cited in Polyakov, A.B. Archived 2021-07-23 at the Wayback Machine (2016) "On the Existence of the Dai Co Viet State in Vietnam in the 10th - the Beginning of 11th Centuries" Vietnam National University, Hanoi's Journal of Science Vol 32. Issue 1S. p. 53 (in Vietnamese)

- ^ Kiernan (2019), p. 141.

- ^ Kiernan (2019), p. 137.

- ^ Taylor (2013), p. 53.

- ^ Kiernan (2019), p. 144.

- ^ Taylor (2013), p. 54.

- ^ Kiernan (2019), p. 146.

- ^ Hall (2019), p. 180.

- ^ Taylor (2013), pp. 58–60.

- ^ Taylor (2013), p. 60.

- ^ Taylor (2013), p. 62.

- ^ Taylor (2013), p. 63.

- ^ Bielenstein (2005), p. 50.

- ^ Taylor (2013), pp. 70, 74.

- ^ Coedes (2015), p. 84.

- ^ Bielenstein (2005), p. 685.

- ^ Kiernan (2019), p. 136.

- ^ Taylor (2013), pp. 72–73.

- ^ Taylor (2013), p. 79.

- ^ Kiernan (2019), pp. 158, 520.

- ^ Miksic & Yian (2016), p. 435.

- ^ Kiernan (2019), pp. 158, 521.

- ^ Taylor (2013), p. 89.

- ^ Schweyer & Piemmettawat (2011), p. 324.

- ^ Schweyer & Piemmettawat (2011), p. 350.

- ^ Coedes (2015), p. 85.

- ^ Taylor (2013), p. 92.

- ^ Kiernan (2019), p. 163.

- ^ Taylor (2013), p. 94.

- ^ Taylor (2013), p. 95.

- ^ Taylor (2013), p. 96.

- ^ Taylor (2013), p. 98.

- ^ Taylor (2013), pp. 108–109.

- ^ Taylor (2013), pp. 116, 122.

- ^ Coedes (2015), p. 126.

- ^ Taylor (2013), pp. 123–124.

- ^ Baldanza (2016), p. 24.

- ^ Coedes (2015), p. 128.

- ^ Taylor (2013), p. 136.

- ^ Kiernan (2019), p. 170.

- ^ Miksic & Yian (2016), p. 489.

- ^ Kiernan (2019), p. 177.

- ^ Lieberman (2003), p. 368–369.

- ^ Lieberman (2003), p. 368.

- ^ Taylor (2013), p. 144.

- ^ Kiernan 2019, pp. 182–183.

- ^ Kiernan (2019), p. 183.

- ^ Kiernan (2019), p. 190.

- ^ Taylor (2013), pp. 166–167.

- ^ Taylor (2013), p. 168.

- ^ a b c Taylor (2013), p. 169.

- ^ Kiernan (2019), p. 193.

- ^ Lieberman (2003), pp. 373–374.

- ^ Wade (2014), pp. 69–70.

- ^ Kiernan (2019), p. 194.

- ^ Lieberman (2003), p. 375.

- ^ Miksic & Yian (2016), p. 524.

- ^ Taylor (2013), pp. 182–186.

- ^ Taylor (2013), p. 187.

- ^ Taylor (2013), p. 191.

- ^ Taylor (2013), pp. 192–195.

- ^ Taylor (2013), p. 196.

- ^ Taylor (2013), pp. 198–200.

- ^ Taylor (2013), pp. 202–203.

- ^ Dutton, Werner & Whitmore (2012), p. 109.

- ^ Taylor (2013), p. 204.

- ^ Hubert & Noppe (2018), p. 9.

- ^ Lieberman (2003), p. 380.

- ^ Taylor (2013), p. 221.

- ^ Beaujard (2019), pp. 393, 512.

- ^ Kiernan (2019), p. 213.

- ^ Kiernan (2019), p. 214.

- ^ Baldanza (2016), p. 87.

- ^ Baldanza (2016), p. 89.

- ^ Kiernan (2019), p. 217.

- ^ Kiernan (2019), p. 218.

- ^ Kiernan (2019), p. 225.

- ^ Lieberman (2003), p. 35.

- ^ Reid&Tran (2006), p. 10.

- ^ Rush (2018), p. 35.

- ^ Lockhart (2018), p. 198.

- ^ Lieberman (2003), p. 355.

- ^ Whitmore (2009), p. 8.

- ^ Anderson & Whitmore (2014), p. 108.

- ^ Lieberman (2003), pp. 358–360.

- ^ Lieberman (2003), p. 373.

- ^ Taylor (2013), pp. 212–213.

- ^ Kiernan (2019), p. 205.

- ^ Hall 2019, pp. 251–252.

- ^ Taylor (2013), p. 213.

- ^ Taylor (2013), pp. 224–231.

- ^ Taylor (2013), p. 232.

- ^ Lieberman (2003), p. 400.

- ^ Dutton, Werner & Whitmore 2012, p. 92.

- ^ Lieberman (2003), p. 397.

- ^ Kiernan (2019), p. 241.

- ^ Fan (2011), p. 202.

- ^ Fan (2011), p. 203.

- ^ Hall 2019, p. 250.

- ^ Hall 2019, pp. 247–248.

- ^ Hall 2019, p. 36.

- ^ Doge, Bayard (1970). The Fihrist of al-Nadim: A Tenth-Century Survey of Muslim Culture. Columbia University Press. pp. 830–831.

- ^ Baron et al. 2018, p. 17, note: Introduction, edited by Benedict R. O'G. Anderson, Tamara Laos, Stanley J. O'Connor, Keith W. Taylor, and Andrew C. Willford.

- ^ Schweyer & Piemmettawat (2011), p. 221.

- ^ Kiernan (2019), p. 107.

- ^ Kiernan (2019), p. 151.

- ^ Kiernan (2019), p. 174.

- ^ Schweyer & Piemmettawat (2011), p. 361.

- ^ Kiernan (2019), p. 157.

- ^ Whitmore (2009), pp. 7–8.

- ^ Schweyer & Piemmettawat (2011), p. 229.

- ^ Lieberman (2003), p. 357.

- ^ Kiernan (2019), p. 165.

- ^ Miksic & Yian (2016), p. 431.

- ^ Miksic & Yian (2016), p. 433.

- ^ Miksic & Yian (2016), p. 432.

- ^ Taylor (2013), p. 69.

- ^ Taylor (2013), p. 289–290.

- ^ Kiernan (2019), p. 242.

- ^ Taylor (2013), p. 242.

- ^ Miksic & Yian (2016), p. 491.

- ^ Schweyer & Piemmettawat (2011), p. 261.

- ^ Schweyer & Piemmettawat (2011), p. 323.

- ^ Schweyer & Piemmettawat (2011), p. 272.

- ^ Schweyer & Piemmettawat (2011), p. 308.

Sources

- Andaya, Barbara Watson; Andaya, Leonard Y. (2015). A History of Early Modern Southeast Asia, 1400–1830. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-88992-6.

- Anderson, James A.; Whitmore, John K. (6 November 2014). China's Encounters on the South and Southwest: Reforging the Fiery Frontier Over Two Millennia. Leiden: BRILL. ISBN 978-9-0042-8248-3. Archivedfrom the original on 5 November 2023. Retrieved 26 November 2022.

- Baldanza, Kathlene (2016). Ming China and Vietnam: Negotiating Borders in Early Modern Asia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781316531310.

- Baron, Samuel; Borri, Christoforo; Dror, Olga; Taylor, Keith W. (2018). Views of Seventeenth-Century Vietnam: Christoforo Borri on Cochinchina and Samuel Baron on Tonkin. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-1-501-72090-1.

- Beaujard, Philippe (2019), The Worlds of the Indian Ocean: Volume 2 From the Seventh Century to the Fifteenth Century CE, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-10864-477-8

- Bielenstein, Hans (2005), Diplomacy and Trade in the Chinese World, 589-1276, Brill

- Chamberlain, James R. (2000). "The origin of the Sek: implications for Tai and Vietnamese history" (PDF). In Burusphat, Somsonge (ed.). Proceedings of the International Conference on Tai Studies, July 29–31, 1998. Bangkok, Thailand: Institute of Language and Culture for Rural Development, Mahidol University. ISBN 974-85916-9-7. Archived(PDF) from the original on 2012-03-31. Retrieved 29 August 2014.

- Churchman, Michael (2010), Before Chinese and Vietnamese in the Red River Plain:The Han–Tang Period, Australian National University: Chinese Southern Diaspora Studies, Vol. 4

- Churchman, Catherine (2016). The People Between the Rivers: The Rise and Fall of a Bronze Drum Culture, 200–750 CE. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-1-442-25861-7.

- Coedes, George (2015). The Making of South East Asia (RLE Modern East and South East Asia). Taylor & Francis.

- Chapuis, Oscar (1995). A history of Vietnam: from Hong Bang to Tu Duc. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-313-29622-7.

- Dror, Olga (2007), Cult, Culture, and Authority : Princess Lieu Hanh in Vietnamese History, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 978-0-8248-2972-8

- Dutton, George; Werner, Jayne; Whitmore, John K., eds. (2012). Sources of Vietnamese Tradition. ISBN 978-0-231-51110-0.

- ISBN 978-0-29599-079-8.

- ISBN 978-1-349-16521-6.

- Hall, Kenneth R. (2019). Maritime Trade and State Development in Early Southeast Asia. University of Hawaii Press.

- Hoang, Anh Tuấn (2007). Silk for Silver: Dutch-Vietnamese relations, 1637–1700. Brill. ISBN 978-9-04-742169-6.

- Hubert, Jean-François; Noppe, Catherine (2018), Arts du Viêtnam: La fleur du pêcher et l'oiseau d'azur, Parkstone International, ISBN 978-1-78310-815-2

- ISBN 978-0-190-05379-6.

- Li, Tana (2018). Nguyen Cochinchina: Southern Vietnam in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. ISBN 978-1-501-73257-7.

- Li, Yu (2020). The Chinese Writing System in Asia: An Interdisciplinary Perspective. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-00-069906-7.

- Lieberman, Victor (2003). Strange Parallels: Integration of the Mainland Southeast Asia in Global Context, c. 800-1830, Vol 1. Cambridge University Press.

- Lockhart, Bruce M. (2018), In Search of "Empire" in Mainland Southeast Asia, pp. 195–214, Bloomsbury Publishing, ISBN 978-1-47259-123-4

- Nguyen, Tai Can (1997). Giáo trình lịch sử ngữ âm tiếng Việt Sơ thảo. Nxb. Giáo dục.

- Nguyen, Tai Thu (2008). The History of Buddhism in Vietnam. Council for Research in Values and Philosophy. ISBN 978-1-565-18097-0.

- ISBN 978-1-317-27903-7.

- Reid, Anthony; Tran, Nhung Tuyet (2006). Viet Nam: Borderless Histories. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-1-316-44504-4.

- Rush, James R. (2018), Southeast Asia: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19024-877-2

- Schafer, Edward Hetzel (1967), The Vermilion Bird: T'ang Images of the South, Los Angeles: University of California Press, ISBN 9780520011458

- Schweyer, Anne-Valérie; Piemmettawat, Paisarn (2011), Viêt Nam histoire arts archéologie, Olizane, ISBN 978-2-88086-396-8

- Tarling, Nicholas (1999). The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia. ISBN 978-0-521-66372-4.

- Taylor, Keith Weller (1983), The Birth of the Vietnam, University of California Press, ISBN 9780520074170

- ISBN 978-1-107-24435-1.

- Taylor, K. W. (2018). Whitmore, John K. (ed.). Essays Into Vietnamese Pasts. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-1-501-71899-1.

- Wade, Geoff (2014), "The "native office" system: A Chinese mechanism for southern territorial expansion over two millennia", in Wade, Geoff (ed.), Asian Expansions: The Historical Experiences of Polity Expansion in Asia, Taylor & Francis, pp. 69–91, ISBN 9781135043537

- Whitmore, John K. (2009), Religion and Ritual in the Royal Courts of Dai Viet, Asia Research Institute

Further reading

- Bridgman, Elijah Coleman (1840). Chronology of Tonkinese Kings. Harvard University. pp. 205–212. ISBN 9781377644080.

- Aymonier, Etienne (1893). The Imperial and Asiatic Quarterly Review and Oriental and Colonial Record. ISBN 978-1149974148.

- Cordier, Henri; Yule, Henry, eds. (1993). The Travels of Marco Polo: The Complete Yule-Cordier Edition : Including the Unabridged Third Edition (1903) of Henry Yule's Annotated Translation, as Revised by Henri Cordier, Together with Cordier's Later Volume of Notes and Addenda (1920). Courier Corporation. ISBN 9780486275871.

- Harris, Peter (2008). The Travels of Marco Polo, the Venetian. Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0307269133.

- Wade, Geoff. tr. (2005). Southeast Asia in the Ming Shi-lu: an open access resource. Singapore: Asia Research Institute and the Singapore E-Press, National University of Singapore.

- ISBN 9788120605350.

- Relazione de’ felici successi della santa fede predicata dai Padri della Compagnia di Giesu nel regno di Tunchino (Rome, 1650)

- Tunchinesis historiae libri duo, quorum altero status temporalis hujus regni, altero mirabiles evangelicae predicationis progressus referuntur: Coepta per Patres Societatis Iesu, ab anno 1627, ad annum 1646 (Lyon, 1652)

- Histoire du Royaume de Tunquin, et des grands progrès que la prédication de L’Évangile y a faits en la conversion des infidèles Depuis l’année 1627, jusques à l’année 1646 (Lyon, 1651), translated by Henri Albi

- Divers voyages et missions du P. Alexandre de Rhodes en la Chine et autres royaumes de l'Orient (Paris, 1653), translated into English as Rhodes of Viet Nam: The Travels and Missions of Father Alexandre de Rhodes in China and Other Kingdoms of the Orient (1666)

- La glorieuse mort d'André, Catéchiste (The Glorious Death of Andrew, Catechist) (pub. 1653)

- Royal Geographical Society, The Journal of the Royal Geographical Society: Volume 7 (1837)

External links

- "Dai Viet – Historical Kingdom, Vietnam". Encyclopedia Britannica. Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc. 2019.

![Phổ Minh Temple, built in ca. 1262.[185]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/51/Pho_Minh_Pagoda_during_festival_-_Th%C3%A1p_Ph%E1%BB%95_Minh_m%C3%B9a_l%E1%BB%85_h%E1%BB%99i_002.jpg/112px-Pho_Minh_Pagoda_during_festival_-_Th%C3%A1p_Ph%E1%BB%95_Minh_m%C3%B9a_l%E1%BB%85_h%E1%BB%99i_002.jpg)

![The One Pillar Pagoda. Constructed around 1050 by Emperor Lý Thái Tông,[186] destroyed in 1952.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f4/Chua_Mot_Cot.jpg/150px-Chua_Mot_Cot.jpg)

![Bảo Nghiêm Pagoda, in Bút Tháp Temple, built c. 1647.[187]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/2d/Bao_Nghiem_Tower_2.jpg/109px-Bao_Nghiem_Tower_2.jpg)

![The pagoda of Trấn Quốc Pagoda, c. 1615.[188]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b2/Tran_Quoc_pagoga.jpg/100px-Tran_Quoc_pagoga.jpg)

![Dâu Temple, c. 1647.[189]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/ce/ChuaDau_Thap.JPG/112px-ChuaDau_Thap.JPG)