174567 Varda

Synodic rotation period | 5.61 h[8] or 5.91 h (single-peaked)[9] 11.82 h (double-peaked)[9] | |

| Albedo | 0.099±0.002 (primary)[7] 0.102+0.024 −0.024[10] | |

|---|---|---|

Spectral type | IR (moderately red)[8] B−V=0.886±0.025[8] V–R=0.55±0.02[11] V−I=1.156±0.029[8] | |

| 20.5[12] | ||

| 3.81±0.01 (primary)[7] 3.097±0.060[8] 3.4[1] | ||

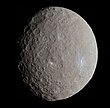

174567 Varda (provisional designation 2003 MW12) is a binary

Astronomer Michael Brown estimates that, with an absolute magnitude of 3.5 and a calculated diameter of approximately 700–800 kilometers (430–500 miles),[14][15] it is likely a dwarf planet.[16] However, William M. Grundy et al. argue that objects in the size range of 400–1000 km, with albedos less than ≈0.2 and densities of ≈1.2 g/cm3 or less, have likely never compressed into fully solid bodies, let alone differentiated, and so are highly unlikely to be dwarf planets.[17] It is not clear if Varda has a low or a high density.

Discovery and orbit

Varda was discovered in March 2006, using imagery dated from 21 June 2003, by

It orbits the Sun at a distance of 39.5–52.7

Name

The names for Varda and its moon were announced by the Minor Planets Center on 16 January 2014.

The use of

Satellite

Varda has one known satellite, Ilmarë (or Varda I), which was discovered in 2009. It is estimated to be about 350 km in diameter (about 50% that of its primary), constituting 8% of the system mass, or 2×1019 kg, assuming its density and albedo are the same as that of Varda.[b]

The Varda–Ilmarë system is tightly bound, with a semimajor axis of 4809±39 km (about 12 Varda radii) and an orbital period of 5.75 days.

Physical properties

Based on its apparent brightness and assumed albedo, the estimated combined size of the Varda–Ilmarë system is 792+91

−84 km, with the size of the primary estimated at 722+82

−76 km.

On 10 September 2018, Varda's projected diameter was measured to be 766±6 km via a stellar occultation, with a projected

The rotation period of Varda is unknown; it has been estimated at 5.61 hours in 2015,[8] and more recently (in 2020) as either 4.76, 5.91 (the most likely value), 7.87 hours, or twice those values.[7] The large uncertainty in Varda's rotation period yields various solutions for its density and true oblateness; given a most likely rotation period of 5.91 or 11.82 hours, its bulk density and true oblateness could be either 1.78±0.06 g/cm3 and 0.235 or 1.23 g/cm3 and 0.080, respectively.[7]

The surfaces of both the primary and the satellite appear to be red in the visible and near-infrared parts of the spectrum (spectral class IR), with Ilmarë being slightly redder than Varda. The spectrum of the system does not show water absorption but shows evidence of methanol ice.[citation needed]

See also

- (55565) 2002 AW197 – a similar trans-Neptunian object by orbit, size, and color

Notes

References

- ^ a b c d e f g "JPL Small-Body Database Browser: 174567 Varda (2003 MW12)" (2019-05-04 last obs.). Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 30 May 2019. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- ^ a b c d e "174567 Varda (2003 MW12)". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- ^ "List of Transneptunian Objects". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- ^ "MPEC 2009-P26 :Distant Minor Planets (2009 AUG. 17.0 TT)". Minor Planet Center. 7 August 2009. Retrieved 24 August 2009.

- Marc W. Buie. "Orbit Fit and Astrometric record for 174567". SwRI (Space Science Department). Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- ^ 3-sigma.)

- ^ S2CID 221095753.

- ^ S2CID 44546400.

- ^ S2CID 119244456.

- ^ S2CID 54222700.

- S2CID 125183388.

- ^ a b "AstDys (174567) Varda Ephemerides". Department of Mathematics, University of Pisa, Italy. Archived from the original on 24 November 2019. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- ^ Johnston, Wm. Robert (31 January 2015). "Asteroids with Satellites Database – (174567) Varda and Ilmare". Johnston's Archive. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- ^ Ceravolo, D.; Ceravolo, P. (26 July 2019). "(174567) Varda, 2018 September 10 occultation". asteroidoccultation.com. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- ^ Braga-Ribas, Felipe; Sicardy, Bruno; Assafin, Marcelo; Ortiz, José-Luis; Camargo, Julio; Desmars, Josselin; et al. (September 2019). The stellar occultation by the TNO (174567) Varda of September 10, 2018: size, shape and atmospheric constraints (PDF). EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2019. Vol. 13. European Planetary Science Congress. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- ^ Brown, Michael E. "How many dwarf planets are there in the outer solar system?". California Institute of Technology. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ W.M. Grundy, K.S. Noll, M.W. Buie, S.D. Benecchi, D. Ragozzine & H.G. Roe, 'The Mutual Orbit, Mass, and Density of Transneptunian Binary Gǃkúnǁʼhòmdímà ((229762) 2007 UK126)', Icarus (forthcoming, available online 30 March 2019) Archived 7 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine DOI: 10.1016/j.icarus.2018.12.037,

- doi:10.1086/511155.

- ^ Miller, Kirk (26 October 2021). "Unicode request for dwarf-planet symbols" (PDF). unicode.org.

External links

- List of binary asteroids and TNOs, Robert Johnston, johnstonsarchive.net

- LCDB Data for (174567) Varda, Collaborative Asteroid Lightcurve Link

- (174567) 2003 MW12 Precovery Images

- 174567 Varda at AstDyS-2, Asteroids—Dynamic Site

- 174567 Varda at the JPL Small-Body Database