1944 Cuba–Florida hurricane

United States East Coast, Atlantic Canada, Greenland | |

| IBTrACS | |

Part of the 1944 Atlantic hurricane season |

The 1944 Cuba–Florida hurricane (also known as the 1944 San Lucas hurricane and the Sanibel Island Hurricane of 1944)

The disturbance began suddenly over the western Caribbean Sea, strengthening into a

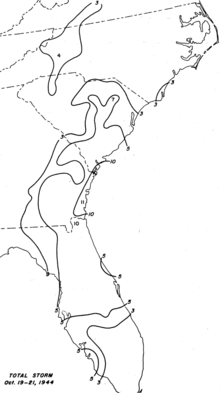

A gradual weakening trend began after the hurricane crossed Cuba, attenuated by the storm's large size. It crossed the

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

The origin of this major hurricane was traced to a tropical disturbance that moved into the western

Two days later, the slow-moving hurricane took a more westward trajectory and passed south of

The hurricane's interaction with Cuba caused the winds to taper slightly, bringing the storm down from its peak intensity to a Category 3 hurricane over the

Warnings and preparations

The

The two major hurricanes of the 1944 season, the September hurricane, and the ... [Cuba–Florida hurricane], had circulation depth well above the top of ordinary pilot balloon observations. It was the ... [rawinsonde] data reaching to much greater height that told the story of future movements, and without them future movements could not have been indicated with as much certainty in the forecast. ... It is urgently recommended that the Weather Bureau lend all possible support to the establishment of additional ... [rawinsonde sites] in the Caribbean and Gulf area to further implement the hurricane warning service.

— Grady Norton, in his summary of the 1944 hurricane season[9]

Cuba evacuated residents from its western low-lying coasts. The storm was considered the strongest hurricane to threaten the island nation since that of

The

On October 19, 125 people were evacuated from Sullivan's Island and Isle of Palms in South Carolina and housed at a county hall.[26]: 1 Residents of Avon, North Carolina, were evacuated to Manteo and Elizabeth City late that day in advance of the weakened storm's approach.[27] Five hundred people evacuated Long Beach Island off mainland New Jersey ahead of the hurricane's extratropical stages.[28]

Impact

In the Monthly Weather Review, the United States Weather Bureau enumerated 318 deaths from the hurricane, noting that reports possibly indicating more deaths were yet to be received from Cuba and the Cayman Islands. The hurricane caused over $100 million in damage across its path.[8]

Caribbean Sea

| Precipitation | Storm | Location | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | mm | in | |||

| 1 | 794.8 | 31.29 | Unnamed, 1944 | Grand Cayman Island |

[29] |

| 2 | 577 | 22.72 | Alberto, 2006 | Owen Roberts International Airport | [30] |

| 3 | 552.2 | 21.74 | Isidore, 2002 | Cayman Brac | [31] |

| 4 | 451.4 | 17.77 | Paloma, 2008 | Cayman Brac | [32] |

| 5 | 308.4 | 12.14 | Ivan, 2004 | Grand Cayman Island | [33] |

| 6 | 292.1 | 11.50 | Hattie, 1961 | Grand Cayman Island | [34] |

| 7 | 229.1 | 9.02 | Nicole, 2010 | Owen Roberts International Airport | [35] |

| 8 | 165.6 | 6.52 | Michelle, 2001 | Grand Cayman Island | [36] |

The hurricane brought

Cuba was the nation hardest hit by the hurricane,[8] though the full extent of casualties remains unknown as reports from rural areas of the island were never realized.[29] Damage was most severe in eastern Pinar del Río. A powerful storm surge killed 20 people in a small village.[8] The coastal port of Surgidero de Batabanó was destroyed, and 24 deaths were reported. The port's entire fishing fleet—numbering over 20 schooners—was carried inland by the storm surge,[44] as was a Standard Oil barge that ended up 10 mi (16 km) inland. Havana Harbor was forced to close because of excessive debris and sunken craft in its waters.[8] Two schooners running cargo routes between Havana and Miami sank in the harbor, as well as Cuban and Peruvian submarine chasers. One capsized vessel blocked the entrance to the harbor, preventing through traffic.[45] A wind gust of 163 mph (262 km/h) was documented in Havana while the eye passed 10–15 mi (16–24 km) to the west;[38] this was the strongest gust measured in Cuba until Hurricane Gustav in 2008. Hurricane-force winds were felt for 14 hours with gusts exceeding 125 mph (201 km/h) for seven hours.[46] The strong winds cut off most electricity in Havana and government telecommunications in Nueva Gerona, the capital of Isla de la Juventud, for three days.[13][47][48] Buildings in Havana suffered extensively, exacerbated by felled trees and flying debris. Administrative buildings including the Presidential Palace and the American embassy sustained considerable damage. Preliminary estimates of the total loss incurred by the city reached several hundred thousand U.S. dollars.[49] There were seven deaths and four hundred injuries.[50] The damage on Isla de la Juventud was extensive but less than initially feared.[51]

In total, about half the crops in the outlying areas of Havana were lost, as well as 90 percent of tobacco warehouses.[52] The storm's effects on the Cuban sugar crop remained uncertain, with estimates ranging from a four percent loss to a net increase due to beneficial rainfall.[53] The total loss of food in Cuba was estimated by the U.S. embassy to be worth $3,000,000. This led to food shortages in the Cuban provinces of La Habana and Matanzas and the Sabana-Camagüey Archipelago.[48][54]

Florida

The hurricane caused $63 million in damages—largely to crops—in Florida.

On October 15, showers streaming north from the hurricane produced heavy rain and 25 mph (40 km/h) gusts over Florida. An instruction flight out of

On the Dry Tortugas, an

The majority of the $10–$13 million toll inflicted to property occurred along the coast, particularly from storm surge.[16] It was highest on the western coast between Sarasota and the Everglades, the greatest tide-related damage occurring along the beaches of Fort Myers.[8] At least fifteen cottages were destroyed on Estero Island, where Fort Myers Beach is located, as well as the island's fishing pier. The entire island was inundated under 3–6 ft (0.91–1.83 m) of seawater, flooding buildings. One apartment complex was half destroyed, part of its foundation caving in. Other longstanding landmarks on Fort Myers Beach were either destroyed or sustained severe damage, and many ships were lost or grounded well inland.[65] The surge accumulated upstream in the Caloosahatchee River, flooding roads with 3–5 ft (0.91–1.52 m) of water.[66]

The hurricane's highest storm surge measured in Florida was 12.28 ft (3.74 m) above mean low tide at

Damage was widespread across the western coast of the Florida peninsula, though its severity varied greatly.[72] The Sarasota and Venice areas where the hurricane made landfall were particularly hard hit.[4] Numerous groves in the region were damaged by high gusts. The combination of fallen trees, downed power lines, and storm surge blocked roadways. Punta Gorda farther south mostly avoided the storm's damaging effects, though downed trees were reported at nearby Nocatee and Arcadia.[73] Communication service in Fort Myers suffered greatly, limiting connectivity to proximate locales.[74] Sustained winds at Page Field were clocked at 90 mph (140 km/h) with gusts exceeding 100 mph (160 km/h).[66]

Trees were downed in St. Petersburg by gusts to 90 mph (140 km/h).[45] Power outages were extensive, exacerbated by an unexpected short-circuiting of an electrical plant during the storm. These outages disrupted the city's streetcar and water pump systems.[45] Windows were blown out of 20 storefronts, and roofs were torn off some homes.[75] Structural damage was minor overall, with damage evaluated at $25,000–$50,000.[76] Damage from citrus losses and property damage in the rest of Pinellas County was valued at $1,000,000.[77] Offshore, nine people were killed, and three crew members survived, after their ship sank at the mouth of Tampa Bay;[8][78] Tampa suffered similarly to St. Petersburg, and experienced a lull in the winds as the center of the hurricane passed overhead.[45] Plate glass windows and storefronts in the downtown area were broken.[45] Short-circuiting wires triggered by the storm caused two major fires, destroying a home and burning most of a shipyard shop;[75][79] Tampa firefighters also responded to another eight fires during the hurricane, though these caused minor damage.[80] Strong winds uprooted trees in the Davis Islands and Gulfport along the coast of the Tampa Bay area.[45][81] Similarly, downed trees were characteristic of the damage in Clearwater. Roofs of older buildings were torn by the strong winds, though damage overall was slight.[82]

Although storm damage in Miami was relatively minor, two people were killed—one from a downed electric line and another from a traffic collision—in the greater metropolitan area.[83] Early green bean and tomato crops in neighboring Palm Beach County were ruined by the hurricane. Between 500–900 acres (200–360 ha) of snap bean crops were lost throughout the Everglades, battered by excessive rainfall of 8–10 in (200–250 mm), but growers were optimistic the rains would later lead to improved harvests.[84] A 300 ft (91 m)-stretch of seawall was destroyed in El Cid Historic District along with an adjacent dock; this was the only structural damage in West Palm Beach.[85]

Of Florida's interior cities, Orlando saw the most severe damage, amounting to several million dollars.[16] While reports of severe property damage were relatively infrequent, damage to ancillary structures and roofs was widespread.[89] Approximately 600–800 homes and numerous stores were damaged.[68] The hurricane disrupted most communications in Orlando and surrounding communities outside of downtown; only two cables linking the city with Jacksonville remained in service.[89] Felled trees blocked a third of the city streets.[54] Orlando recorded its rainiest 24-hour period since 1910, observing 7.49 in (190 mm) between October 18–19. Damage across Orange County was preliminarily estimated between $3–5 million, the damage in Orlando accounting for roughly half of the toll. One person was electrocuted in the downtown area. The Orlando Reporter-Star called the hurricane the Orlando's worst storm in 50 years. At nearby Winter Park, power failures caused the municipal water system to shut down. Many homes in Gotha were roofless from the storm's winds. Between Gotha and Windermere, more than half of the grapefruit trees were stripped of their fruits, as well as 10–20 percent of orange trees and five percent of tangerines.[89]

Elsewhere in the Florida interior, two hangars at Alachua Army Air Field near Gainesville collapsed. Some trees in Gainesville were toppled onto houses. Severe property damage was noted in Bartow, and roofs were torn from a school and several homes in Williston and Groveland. Damage was limited primarily to crops in the Palatka and Crescent City areas, with only minor losses sustained otherwise.[54] Heavy rains and gusts as high as 75 mph (121 km/h) were recorded in Lakeland, which lost all power during the storm.[90]

Elsewhere in the United States

Total losses in the state of Georgia were estimated at between $250,000–$500,000. Most of the damage occurred before the arrival of the storm's center of circulation. Downed trees blocked streets and highways in several communities. Communication services were scant in some areas as telecommunication and power lines were severed by the storm. Strong winds also damaged the shingles of some buildings to varying degrees. The shipyard in Brunswick, Georgia, was hit particularly hard, several of its buildings and four cranes being damaged. Eastern extents of the city were also inundated by storm surge as far as 1 mi (1.6 km) inland, prompting the evacuation of affected homes.[91] The high wind-swept tides caused coastal inundation throughout the Southeastern U.S. coast, destroying many fishing boats at the Port of Savannah.[8] The highest tides in Georgia occurred in Fort Pulaski, where the sea rose 5.9 ft (1.8 m) above mean sea level.[92] Water damage on the island of St. Simons forced the evacuation of 1,200 people.[26]: 4 The hurricane's heaviest rainfall occurred at the Brunswick airport, where 11.4 in (290 mm) was recorded.[93]

Winds reaching 65 mph (105 km/h) brought down power and communication lines across the Carolinas, leaving much of Charleston, South Carolina, without electricity.[8][94] Tides to 9 ft (2.7 m) inundated low-lying areas of the city, primarily around The Battery.[94] Trees and signage were downed in Florence, located 70 mi (110 km) from the coast. Several railroad coaches traversing the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad just south of Florence were damaged.[69] Heavy rains throughout South Carolina caused $350,000 in damage to property and crops.[95] In northwestern parts of the state, unpicked cotton crops perished.[96] Winds of 30–40 mph (48–64 km/h) damaged corn and lespedeza in North Carolina, constituting most of the $200,000 damage toll wrought by the storm there.[97]

The storm's effects tapered as precipitation and high seas spread north along the

Aftermath

| Costliest U.S. Atlantic hurricanes, 1900–2017 Direct economic losses, normalized to societal conditions in 2018[103] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Hurricane | Season | Cost |

| 1 | 4 "Miami" | 1926 | $235.9 billion |

| 2 | 4 "Galveston" | 1900 | $138.6 billion |

| 3 | 3 Katrina | 2005 | $116.9 billion |

| 4 | 4 "Galveston" | 1915 | $109.8 billion |

| 5 | 5 Andrew | 1992 | $106.0 billion |

| 6 | ET Sandy | 2012 | $73.5 billion |

| 7 | 3 "Cuba–Florida" | 1944 | $73.5 billion |

| 8 | 4 Harvey | 2017 | $62.2 billion |

| 9 | 3 "New England" | 1938 | $57.8 billion |

| 10 | 4 "Okeechobee" | 1928 | $54.4 billion |

| Main article: List of costliest Atlantic hurricanes | |||

In the immediate aftermath, between 5,000 and 7,000 people across Florida were displaced and housed in temporary arrangements; three times as many people required dietary assistance.

The WPB, operating jointly with the Red Cross, made 5,000,000 ft (1,500,000 m) of lumber and 5,000 shingle squares available for repairs and in the Tampa area.[112] The Federal Housing Administration allowed mortgage loans of $5,400 for residents whose homes were destroyed by the hurricane, based on the agency's assessment that "property damage was limited to roofs and broken glass" in the state.[113]

See also

- List of Florida hurricanes (1900–1949)

- 1910 Cuba hurricane – caused extensive damage in western Cuba before affecting much of Florida

- Hurricane Charley – took a similar path through Cuba and Florida, with a significant core of wind damage spanning central Florida

Notes

References

- Citations

- from the original on May 2, 2019. Retrieved May 11, 2019.

- ^ a b Roth, David M. (May 26, 2009). "Tropical Cyclone Rainfall" (PowerPoint Presentation). Camp Springs, Maryland: Weather Prediction Center. Archived from the original on May 31, 2017. Retrieved June 24, 2019.

- ^ Goldenburg, Stan (June 1, 2018). "A3) What is a super-typhoon? What is a major hurricane? What is an intense hurricane?". Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ). 4.11. Miami, Florida: Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. Archived from the original on June 15, 2006. Retrieved August 2, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Landsea, Chris; Anderson, Craig; Bredemeyer, William; Carrasco, Cristina; Charles, Noel; Chenoweth, Michael; Clark, Gil; Delgado, Sandy; Dunion, Jason; Ellis, Ryan; Fernandez-Partagas, Jose; Feuer, Steve; Gamanche, John; Glenn, David; Hagen, Andrew; Hufstetler, Lyle; Mock, Cary; Neumann, Charlie; Perez Suarez, Ramon; Prieto, Ricardo; Sanchez-Sesma, Jorge; Santiago, Adrian; Sims, Jamese; Thomas, Donna; Lenworth, Woolcock; Zimmer, Mark (May 2015). "Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT". Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Metadata). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 1944 – Storm 13 (previously Storm 11) – 2013 Revision. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved August 12, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Sumner, p. 221.

- ^ a b c d e "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. April 5, 2023. Retrieved April 18, 2024.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b c Sumner, p. 222.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Sumner, p. 223.

- ^ ISBN 9780875902975. (subscription required)

- . Retrieved May 11, 2019.

- ^ a b "Havana Boards Up for Storm". Tampa Morning Tribune. No. 292. Tampa, Florida. Associated Press. October 18, 1944. p. 2. Retrieved June 12, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Six Are Dead, Over 20 Hurt by Hurricane". The Evening Telegram. No. 310. Rocky Mount, North Carolina. Associated Press. October 18, 1944. p. 1. Retrieved June 12, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Creeps Through Cuba". The Evening Sun. No. 155. Baltimore, Maryland. Associated Press. October 16, 1944. p. 3. Retrieved May 11, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Severe Hurricane Threat to Mexico". Valley Evening Monitor. No. 92. McAllen, Texas. Associated Press. October 16, 1944. p. 1. Retrieved May 11, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bennett, W. J. (October 1944). "Florida Section". Climatological Data. 48 (10). Jacksonville, Florida: National Climatic Data Center: 55.

- ^ "Key West May Miss Brunt of Hurricane". Miami Daily News. No. 308. Miami, Florida. October 18, 1944. p. 1. Retrieved June 12, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Florida Waits Hurricane". Orlando Reporter. No. 4737. Orlando, Florida. United Press International. October 18, 1944. pp. 1–2. Retrieved June 12, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^

- ^ "Police, Relief Agencies Ready for Emergency". St. Petersburg Times. No. 86. St. Petersburg, Florida. October 18, 1944. pp. 1–2. Retrieved June 12, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^

- ^ a b c "Storm Subsides in Phila. Damage Slight". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Vol. 231, no. 114. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. October 22, 1944. p. 1. Retrieved June 29, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e Barnes, p. 165.

- ^ Knabb, Richard D. (June 10, 2006). Tropical Depression One Advisory Number 2 (National Hurricane Center Public Advisory). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on April 19, 2019. Retrieved July 17, 2019.

- ^ "Weather" (PDF). Cayman Islands 2002 Annual Report & Official Handbook. Georgetown, Grand Cayman, Cayman Islands: Government of the Cayman Islands. June 2003. p. 129. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 15, 2020. Retrieved July 17, 2019.

- ^ Brennan, Michael J. (April 14, 2009). Hurricane Paloma (PDF) (Tropical Cyclone Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 19, 2017. Retrieved July 17, 2019.

- ^ Stewart, Stacy R. (August 11, 2011). Hurricane Ivan (PDF) (Tropical Cyclone Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 18, 2019. Retrieved July 17, 2019.

- ^ Dunn, Gordon (October 30, 1961). "Miami Weather Bureau bulletin for press radio and TV 2 PM EST 30 October 1961" (GIF). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on June 28, 2017. Retrieved July 17, 2019.

- ^ Annual Report 2010–2011 (PDF) (Report). Grand Cayman, Cayman Islands: Hazard Management Department of the Cayman Islands. n.d. p. 9. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 1, 2017. Retrieved July 17, 2019.

- ^ Beven, Jack (January 23, 2002). Hurricane Michelle (PDF) (Tropical Cyclone Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. p. 8. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 13, 2019. Retrieved July 17, 2019.

- Montreal, Quebec. The Canadian Press. October 18, 1944. p. 1. Retrieved May 11, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Barnes, p. 164.

- ISBN 9780792324621. Retrieved June 24, 2019.

- ISBN 9780520096561. Retrieved June 24, 2019.

- ^ a b "Grand Cayman Damage Great; Ships Wrecked". Tampa Morning Tribune. No. 300. Tampa, Florida. October 26, 1944. p. 16. Retrieved June 24, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "All Crops on Grand Cayman Destroyed by Hurricane". The Daily Gleaner. No. 227. Kingston, Jamaica. October 17, 1944. p. 1 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "After the Hurricane in the Cayman Islands". The Daily Gleaner. No. 227. Kingston, Jamaica. October 20, 1944. p. 1 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^

- ^

- ^ Rubiera, José (October 8, 2014). "Crónica del Tiempo: Los huracanes y octubre". CubaDebate (in Spanish). Havana, Cuba: Universidad de las Ciencias Informáticas. Archived from the original on June 7, 2019. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- ^ a b c "Violent Hurricane Leaves Thousands in Cuba Destitute". The Daily Gleaner. No. 231. Kingston, Jamaica. October 21, 1944. p. 1 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ISBN 9789592300019. Retrieved June 30, 2019.

- ^

- United States Treasury Department. Archived(PDF) from the original on August 18, 2016. Retrieved June 23, 2019.

- ^

- S2CID 133937951.(subscription required)

- United States Government Printing Office. p. 7. Retrieved June 29, 2019.

- ^ Quinby, E. J. (October 1944). "MM08838-26x". Flickr. Archived from the original on January 31, 2019. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- ^

- "Floods Recede in Key West', p. 1-A Archived June 24, 2019, at the Wayback Machine

- "Key West: Floods Recede", p. 6-A

- ^ Clark, p. 12.

- ^ a b Clark, p. 13.

- ^ "Red Coconut, 15 Cottages Wiped Away". Fort Myers News-Press. No. 339. Fort Myers, Florida. October 20, 1944. pp. 1, 4. Retrieved June 24, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^

- ^ Brouillette, Daniel J. (October 20, 2016). Hurricane Matthew — a Major 2016 Hurricane That Florida But Had Major Effects (PDF) (Report). Tallahassee, Florida: Florida Climate Center. p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 23, 2016. Retrieved June 30, 2019.

- ^ a b c "Storm Reports from Over State". The Tampa Daily Times. No. 221. Tampa, Florida. October 20, 1944. pp. 1, 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^

- ^ a b c "Storm Swamps Shrimp Boats Off Cocoa-Canaveral Coast". Orlando Reporter-Star. No. 4739. Orlando, Florida. October 20, 1944. p. 1. Retrieved June 24, 2019.

- ^

- ^ "Winds and Rain Ruin Bean Crop". The Palm Beach Post. No. 216. West Palm Beach, Florida. October 20, 1944. p. 1. Retrieved June 24, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Wind-Buffeted City Gets Back to Normal Operation". The Palm Beach Post. No. 216. West Palm Beach, Florida. October 20, 1944. pp. 1, 7. Retrieved June 24, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Patterson, W. W. (October 20, 1944). "Vast Scene of Desolation in All Central Florida Groves". Orlando Reporter-Star. No. 4739. Orlando, Florida. United Press International. p. 1. Retrieved June 24, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e "Army to Help City; No Electric Service; Citrus Loss Heavy". Orlando Reporter-Star. No. 4739. Orlando, Florida. October 20, 1944. pp. 1, 3. Retrieved June 24, 2019.

- ^ Knarr, A. J. (October 1944). "Georgia Section". Climatological Data. 48 (10). Atlanta, Georgia: National Climatic Data Center: 40.

- ^ Ho, Francis P. (September 1974). Storm Tide Frequency Analysis for the Coast of Georgia (PDF) (NOAA Technical Memorndum). Silver Spring, Maryland: National Weather Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 2, 2017. Retrieved June 30, 2019.

- ^ Schoner, R. W.; Molansky, S. (July 1956). "Storms in the South Atlantic Coastal Region" (PDF). Rainfall Associated with Hurricanes (And Other Tropical Disturbances) (Report). Washington, D.C.: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. p. 196. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 21, 2017. Retrieved June 23, 2019.

- ^

- ^ South Carolina State Climatology Office. "Hurricanes and Tropical Storms Affecting South Carolina 1940–1949". Tropical Storms and Hurricanes: 1940–1949. Columbia, South Carolina: South Carolina Department of Natural Resources. Archived from the original on January 1, 2019. Retrieved June 23, 2019.

- ^ "Heavy S.C. Rainfall Last Week Damaged Unharvested Crops". The Index-Journal. No. 243. Greenwood, South Carolina. October 26, 1944. p. 5. Retrieved June 25, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Kichline, H. E. (October 1944). "North Carolina Section". Climatological Data. 48 (10). Raleigh, North Carolina: National Climatic Data Center: 37.

- .

- ^ "Hurricane Did Little Damage in This State". The Evening Leader. Vol. 80, no. 109. Staunton, Virginia. Associated Press. October 21, 1944. p. 1. Retrieved June 29, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Rains, Winds Hit Area but Storm Passes". Daily Press. Vol. 49, no. 286. Newport News, Virginia. October 21, 1944. p. 5. Retrieved June 29, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Storm to End by Noon, Local Bureau Says". The Sun. Vol. 215, no. 136. Baltimore, Maryland. October 21, 1944. p. 16. Retrieved June 29, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Below-Freezing Predicted in Wake of Heavy Storm". The Boston Sunday Globe. Vol. 146, no. 114. Boston, Massachusetts. October 22, 1944. pp. 1, 17. Retrieved June 29, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Below-Freezing Predicted in Wake of Heavy Storm", p. 1 Archived June 29, 2019, at the Wayback Machine

- "Storm", p. 17 Archived October 10, 2019, at the Wayback Machine

- .

- ^ "Gleaner Storm Relief Fund". The Daily Gleaner. No. 228. Kingston, Jamaica. October 18, 1944. p. 3 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Winds Still Strong in North Carolina". The Tampa Daily Times. No. 221. Tampa, Florida. Associated Press. October 20, 1944. pp. 1, 3. Retrieved June 24, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Decisions on Citrus Prices Still Awaited". Tampa Sunday Tribune. No. 303. Tampa, Florida. October 29, 1944. p. 8. Retrieved June 25, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Growers of Citrus Ask Higher Prices". Spokane Daily Chronicle. No. 36. Spokane, Washington. Associated Press. November 2, 1944. p. 7 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Second Hike in Citrus Price Held Possible". Orlando Reporter-Star. No. 4752. Orlando, Florida. Associated Press. November 4, 1944. p. 1. Retrieved June 25, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Red Cross, WPB Offer Assistance". The Tampa Daily Times. No. 221. Tampa, Florida. October 20, 1944. p. 2. Retrieved June 24, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Only Few Homes Storm Wrecked". Miami Daily News. No. 314. Miami, Florida. Associated Press. October 21, 1944. p. 3–A. Retrieved June 25, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- Sources

- Barnes, Jay (May 2007). "Hurricanes in the Sunshine State, 1900–1949". Florida's hurricane history (2nd ed.). Chapel Hill, North Carolina: The ISBN 9780807858097.

- Clark, Ralph R. (1998). The Impact of Hurricane Georges on the Carbonate Beaches of the Florida Keys (PDF). Engineering, Hydrology and Geology Program (Report). Florida Department of Environmental Protection. Retrieved June 30, 2019.

- Sumner, H. C. (November 1944). "The North Atlantic Hurricane of October 13–21, 1944" (PDF). ]

External links