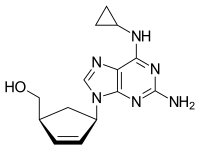

Abacavir

| |

Chemical structure of abacavir | |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /əˈbækəvɪər/ ⓘ |

| Trade names | Ziagen |

| Other names | Abacavir sulfate (USAN US) |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a699012 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 83% |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Elimination half-life | 1.54 ± 0.63 h |

| Excretion | Kidney (1.2% abacavir, 30% 5'-carboxylic acid metabolite, 36% 5'-glucuronide metabolite, 15% unidentified minor metabolites). Fecal (16%) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 165 °C (329 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Abacavir, sold under the brand name Ziagen among others, is a

Abacavir is generally well tolerated.

Abacavir was patented in 1988, and approved for use in the United States in 1998.

Medical uses

Abacavir, in combination with other antiretroviral agents, is

Contraindications

Abacavir is contraindicated for people who have the HLA‑B*5701 allele or who have moderate or severe liver disease (hepatic impairment).[3][4]

Side effects

Common adverse reactions include nausea, headache, fatigue, vomiting, diarrhea, Anorexia (symptom) (loss of appetite), and insomnia (trouble sleeping). Rare but serious side effects include hypersensitivity reaction such as rash, elevated AST and ALT, depression, anxiety, fever/chills, URI, lactic acidosis, hypertriglyceridemia, and lipodystrophy.[13]

Hypersensitivity syndrome

Common symptoms of abacavir hypersensitivity syndrome include

Skin-patch testing may also be used to determine whether an individual will experience a hypersensitivity reaction to abacavir, although some patients susceptible to developing AHS may not react to the patch test.[26]

The development of suspected hypersensitivity reactions to abacavir requires immediate and permanent discontinuation of abacavir therapy in all patients, including patients who do not possess the HLA-B*5701 allele. On 1 March 2011, the FDA informed the public about an ongoing safety review of abacavir and a possible increased risk of heart attack associated with the drug.[27] A meta-analysis of 26 studies conducted by the FDA, however, did not find any association between abacavir use and heart attack[28][29]

Immunopathogenesis

The mechanism underlying abacavir hypersensitivity syndrome is related to the change in the HLA-B*5701 protein product. Abacavir binds with high specificity to the HLA-B*5701 protein, changing the shape and chemistry of the antigen-binding cleft. This results in a change in immunological tolerance and the subsequent activation of abacavir-specific cytotoxic T cells, which produce a systemic reaction known as abacavir hypersensitivity syndrome.[17]

Interaction

Abacavir, and in general NRTIs, do not undergo hepatic metabolism and therefore have very limited (to none) interaction with the CYP enzymes and drugs that effect these enzymes. That being said there are still few interactions that can affect the absorption or the availability of abacavir. Below are few of the common established drug and food interaction that can take place during abacavir co-administration:

- ritonovir may decrease the serum concentration of abacavir through induction of glucuronidation. Abacavir is metabolized by both alcohol dehydrogenase and glucuronidation.[30][31]

- Ethanol may result in increased levels of abacavir through the inhibition of alcohol dehydrogenase. Abacavir is metabolized by both alcohol dehydrogenase and glucuronidation.[30][32]

- Methadone may diminish the therapeutic effect of Abacavir. Abacavir may decrease the serum concentration of Methadone.[33][34]

- Orlistat may decrease the serum concentration of antiretroviral drugs. The mechanism of this interaction is not fully established but it is suspected that it is due to the decreased absorption of abacavir by orlistat.[35]

- Cabozantinib: Drugs from the MRP2 inhibitor (Multidrug resistance-associated protein 2 inhibitors) family such as abacavir could increase the serum concentration of Cabozantinib.[36]

Mechanism of action

Abacavir is a

Pharmacokinetics

Abacavir is given orally and is rapidly absorbed with a high bioavailability of 83%.[38] Solution and tablet have comparable concentrations and bioavailability. Abacavir can be taken with or without food.[39]

Abacavir can cross the blood–brain barrier. Abacavir is metabolized primarily through the enzymes alcohol dehydrogenase and glucuronyl transferase to an inactive carboxylate and glucuronide metabolites. It has a half-life of approximately 1.5-2.0 hours. If a person has liver failure, abacavir's half life is increased by 58%.[40]

Abacavir is eliminated via excretion in the urine (83%) and feces (16%).[41] It is unclear whether abacavir can be removed by hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis.[37]

History

Robert Vince and Susan Daluge along with Mei Hua, a visiting scientist from China, developed the medication in the '80s.[42][43][44]

Abacavir was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on 18 December 1998, and is thus the fifteenth approved antiretroviral drug in the United States.[45] Its patent expired in the United States on 26 December 2009.[citation needed]

Synthesis

References

- FDA. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ "TGA eBS - Product and Consumer Medicine Information Licence". Archived from the original on 24 March 2022. Retrieved 23 August 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f "Ziagen- abacavir sulfate tablet, film coated label". DailyMed. 30 September 2015. Archived from the original on 11 January 2017. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f "Ziagen EPAR". European Medicines Agency. 17 September 2018. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 22 August 2022. Text was copied from this source which is copyright European Medicines Agency. Reproduction is authorized provided the source is acknowledged.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Abacavir Sulfate". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 21 August 2017. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ^ "Drug Name Abbreviations Adult and Adolescent ARV Guidelines". AIDSinfo. Archived from the original on 9 November 2016. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- ^ "What Not to Use Adult and Adolescent ARV Guidelines". AIDSinfo. Archived from the original on 9 November 2016. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- ^ S2CID 31107341.

- ^ a b "Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs or 'nukes') - HIV/AIDS". www.hiv.va.gov. Archived from the original on 9 November 2016. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- ISBN 9783527607495. Archivedfrom the original on 8 September 2017.

- ISBN 9781438102078. Archivedfrom the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ "Abacavir Adverse Reactions". Epocrates Online. Archived from the original on 23 August 2021. Retrieved 9 November 2012.

- from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- PMID 16758424.

- from the original on 26 October 2020. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ^ S2CID 4408811.

- S2CID 9434238.

- S2CID 12923232.

- PMID 20942671.

- S2CID 45896364.

- S2CID 37549824.

- ^ "Information for Healthcare Professionals: Abacavir (marketed as Ziagen) and Abacavir-Containing Medications". Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 24 July 2008. Archived from the original on 11 December 2013. Retrieved 29 November 2013.

- S2CID 2475005.

- PMID 24561393.

- S2CID 2972984.

- ^ "FDA Drug Safety Communication: Safety Review update of Abacavir and possible increased risk of heart attack". Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 1 March 2011. Archived from the original on 13 December 2019. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- ^ "FDA Alert: Abacavir - Ongoing Safety Review: Possible Increased Risk of Heart Attack". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 10 December 2013. Retrieved 29 November 2013.

- S2CID 7997822.

- ^ a b Prescribing information. Ziagen (abacavir). Research Triangle Park, NC: GlaxoSmithKline, July 2002

- S2CID 23591048.

- PMID 10817729.

- S2CID 17609676.

- ^ Dolophine(methadone) [prescribing information]. Columbus, OH: Roxane Laboratories, Inc.; March 2015.

- PMID 26945709.

- ^ Cometriq (cabozantinib) [prescribing information]. South San Francisco, CA: Exelixis, Inc.; May 2016.

- ^ a b Product Information: ZIAGEN(R) oral tablets, oral solution, abacavir sulfate oral tablets, oral solution. ViiV Healthcare (per Manufacturer), Research Triangle Park, NC, 2015.

- S2CID 20131476.

- ^ Jones A (May 2019). "Food requirements for anti-HIV medications". aidsmap.com. Archived from the original on 25 April 2021. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- PMID 15736035.

- S2CID 31107341.

- ^ "Dr. Robert Vince - 2010 Inductee". Minnesota Inventors Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on 15 February 2016. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- ^ "Robert Vince, PhD (faculty listing)". University of Minnesota. Archived from the original on 17 February 2016.

- PMID 9145874.

- ^ Mary Annette Banach. "How HIV Clinicians Acquire Representational Fluency: A Case Study of the HIV Resistance Preceptorship Archived 23 August 2022 at the Wayback Machine", University of California, Berkeley, 2003.

- PMID 11667311.

Further reading

- Dean L (April 2018). "Abacavir Therapy and HLA-B*57:01 Genotype". In Pratt VM, McLeod HL, Rubinstein WS, et al. (eds.). Medical Genetics Summaries. from the original on 26 October 2020. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

External links

- "Abacavir". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Abacavir sulfate". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- Abacavir pathway on PharmGKB