Abram Games

Abram Games | |

|---|---|

| Born | Abraham Gamse 29 July 1914 Whitechapel, London, England |

| Died | 27 August 1996 (aged 82) London, England |

| Education | Saint Martin's School of Art |

| Known for | Graphic design |

| Spouse |

Marianne Salfeld

(m. 1945; died 1988) |

| Website | Official website |

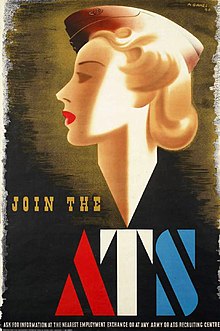

Abram Games OBE, RDI (29 July 1914 – 27 August 1996) was a British graphic designer. The style of his work – refined but vigorous compared to the work of contemporaries – has earned him a place in the pantheon of the best of 20th-century graphic designers. In acknowledging his power as a propagandist, he claimed, "I wind the spring and the public, in looking at the poster, will have that spring released in its mind." Because of the length of his career – over six decades – his work is essentially a record of the era's social history. Some of Britain's most iconic images include those by Games. An example is the "Join the ATS" poster of 1941, nicknamed the "blonde bombshell" recruitment poster. His work is recognised for its "striking colour, bold graphic ideas, and beautifully integrated typography".[1]

Early life and career

Born Abraham Gamse in

World War Two

At the start of World War Two, Games was conscripted into the British Army. He served until 1941 when he was approached by the Public Relations Department of the

Other notable posters included Your Talk May Kill Your Comrades (1942) in which a spiral symbolising gossip originates from a soldiers mouth to become a bayonet attacking three of his comrades. Games used the photographic techniques he had learnt from his father in that and other posters such as He Talked...They Died (1943) part of the Careless Talk campaign.[5] In addition to his poster work, Games completed a number of commissions for the War Artists' Advisory Committee.[7]

Later in the War, Churchill ordered a poster Games had produced to be taken off the wall of the Poster Design in Wartime Britain exhibition at Harrods in 1943. The Army Bureau of Current Affairs, ABCA, had commissioned Games and Frank Newbould to produce posters for a series entitled Your Britain - Fight for It Now. While Newbould produced rural images similar to the pre-war travel posters he had created for several railway companies, Games presented a set of three Modernist buildings that had been built to address poverty, disease and deprivation. The poster that annoyed Churchill most featured the Berthold Lubetkin designed Finsbury Health Centre superseding a ruined building with a child suffering from rickets. Churchill considered this nothing short of a libel on the conditions in British cities and ordered the poster to be removed.[3][6] Ernest Bevin, the war-time Minister of Labour, had another poster in the series removed from the Poster Design in Wartime Britain exhibition organised by the Association of International Artists.[8]

Later career

In 1946, Games resumed his freelance practice and worked for clients such as Royal Dutch Shell, the

Games had been among the first in Britain to see evidence of the atrocities committed at the

Games was also an industrial designer of sorts. Activities in this discipline included the design of the 1947 Cona

In arriving at a poster design, Games would render up to 30 small preliminary sketches and then combine two or three into the final one. In the developmental process, he would work small because, he asserted, if poster designs "don't work an inch high, they will never work." He would also call on a large number of photographic images as source material. Purportedly, if a client rejected a proposed design (which seldom occurred), Games would resign and suggest that the client commission someone else.

In 2013, the National Army Museum, London, acquired a collection of his posters, each signed by Games and in mint condition.[12]

-

Poster by Games advertising tourism for the island of Jersey.

-

British European Airways advertising poster by Games.

Personal life

In October 1945, Games married Marianne Salfeld, the daughter of German orthodox Jewish émigrés, and initially lived with her father in Surbiton, Surrey.[13][14] In 1948, they moved to north London, and lived in the same house until their deaths.[13][5] They had three children, Naomi, Daniel and Sophie.[13][15]

Marianne died in 1988; Games died in London on 27 August 1996.[5]

Exhibitions

- Abram Games, Graphic Designer (1914–1996): Maximum Meaning, Minimum Means, Design Museum, London, 2003

- Abram Games, Maximum Meaning, Minimum Means, The Minories, Colchester, 2011

- Designing the 20th Century: Life and Work of Abram Games, Jewish Museum London, 2014–2015

- Abram Games - Maximum Meaning Minimum Means, Dick Institute Kilmarnock, East Ayrshire, 2015

- The Art of Persuasion: War time posters by Abram Games, National Army Museum, London: 6 April-24 November 2019[16]

References

- ^ ISBN 978-1-84573-473-2.

- ^ a b "Abram Games". Design Museum. 2003. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-904897-92-7.

- ^ a b "Abram Games". University of Brighton Design Archives. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ^ a b c d Alan & Isabella Livingston (28 August 1996). "Obituary:Abraham Games". The Independent. Archived from the original on 29 October 2016. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- ^ a b Smith, David (30 September 2007). "Poster Churchill pulped on show". The Observer. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-300-10890-3.

- ^ ISBN 0-19-861371-7.

- ^ "Stockwell - Victoria Line Tile Motifs". Go London. Archived from the original on 26 January 2016. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- ^ "Exhibition 'Conquest Of The Desert'". Retrieved 22 November 2014.

- ^ a b Moore, Rowan (23 August 2014). "Abram Games, the poster boy with principles". The Observer. Retrieved 24 August 2014.

- ^ Kennedy, Maeve (23 August 2013). "Poster girl of ATS joins National Army Museum". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 August 2013.

- ^ a b c "Abram Games (1914 – 1996)". British Council. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

- ^ "Abram Games and the power of the poster | National Army Museum". www.nam.ac.uk.

- ^ Moore, Rowan (23 August 2014). "Abram Games, the poster boy with principles" – via www.theguardian.com.

- ^ "The art of persuasion: Wartime posters by Abram Games". National Army Museum. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

Further reading

- Amstutz, W.Who's Who in Graphic Art (1962. Zurich: Graphis Press)

- Gombrich, E.H., et al. A. Games: Sixty Years of Design (1990. South Glamorgan, UK: Institute of Higher Education) | ISBN 0-9515777-0-0

- Livingston, Alan and Isabella The Thames and Hudson Dictionary of Graphic Design and Designers (2003. London: Thames and Hudson) | ISBN 0-500-20353-9

- Moriarty, Catherine, et al. Abram Games, Graphic Designer: Maximum Meaning, Minimum Means [exhibition catalogue] (2003. London: Lund Humphries) | ISBN 0-85331-881-6

- Games, Naomi et al. Abram Games: His Life and Work (2003. New York Princeton Architectural Press) | ISBN 1-56898-364-6

- Games, Naomi. Poster Journeys: Abram Games and London Transport (Capital Transport, Mendlesham, UK)