Modern sculpture

Modern sculpture is generally considered to have begun with the work of Auguste Rodin, who is seen as the progenitor of modern sculpture. While Rodin did not set out to rebel against the past, he created a new way of building his works.[2][3] He "dissolved the hard outline of contemporary Neo-Greek academicism, and thereby created a vital synthesis of opacity and transparency, volume and void".[4] Along with a few other artists in the late 19th century who experimented with new artistic visions in sculpture like Edgar Degas and Paul Gauguin, Rodin invented a radical new approach in the creation of sculpture. Modern sculpture, along with all modern art, "arose as part of Western society's attempt to come to terms with the urban, industrial and secular society that emerged during the nineteenth century".[5]

among others.Modernism

The modern sculpture movement can be said to begin at the

Cubist sculpture, in the early 20th century, was a style that developed in parallel with cubist painting, and the formal experiments of Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso. Beginning around 1909 and evolving through the early 1920s cubist artists developed new means of constructing works of art using collage, sculptural assemblage using disparate materials and traditional sculpture making from plaster and clay molds. Some sources name Picasso's 1909 bronze Head of a Woman as the first cubist sculpture.[8]

Artists like

In the early 20th century, during his period of cubist innovation,

Similarly, the work of Constantin Brâncuși at the beginning of the century paved the way for later abstract sculpture. In revolt against the naturalism of Rodin and his late 19th-century contemporaries, Brâncuși distilled subjects down to their essences as illustrated by the elegantly refined forms of his Bird in Space series (1924). These elegantly refined forms became synonymous with 20th-century sculpture.[12] In 1927, Brâncuși won a lawsuit against the U.S. customs authorities who attempted to value his sculpture as raw metal. The suit led to legal changes permitting the importation of abstract art free of duty.[13]

Brâncuși's impact, with his vocabulary of reduction and abstraction, is seen throughout the 1930s and 1940s, and exemplified by artists such as

Post-1950s

Since the 1950s

In the late 1950s and the 1960s, abstract sculptors began experimenting with a wide array of new materials and different approaches to creating their work. Surrealist imagery, anthropomorphic abstraction, new materials and combinations of new energy sources and varied surfaces and objects became characteristic of much new modernist sculpture. Collaborative projects with landscape designers, architects, and landscape architects expanded the outdoor site and contextual integration. Artists such as Isamu Noguchi, David Smith, Alexander Calder, Jean Tinguely, Richard Lippold, George Rickey, Louise Bourgeois, and Louise Nevelson came to characterize the look of modern sculpture.[citation needed]

By the 1960s

Gallery of modern sculpture

-

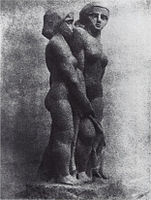

Auguste Rodin, The Three Shades, before 1886, plaster, 97 x 91.3 x 54.3 cm. In Dante's Divine Comedy, the shades, i.e. the souls of the damned, stand at the entrance to The Gates of Hell, pointing to an unequivocal inscription, “Abandon hope, all ye who enter here”. Rodin assembled three identical figures that seem to be turning around the same point.[19]

-

Oviri(Sauvage), partially glazed stoneware, 75 x 19 x 27 cm, Musée d'Orsay, Paris

-

Constantin Brâncuși, 1907–08, The Kiss, Exhibited at the Armory Show and published in the Chicago Tribune, 25 March 1913

-

Constantin Brâncuși, Portrait of Mademoiselle Pogany, 1912, White marble; limestone block, Philadelphia Museum of Art, exhibited at the 1913 Armory Show

-

Alexander Archipenko, 1910–11, Negress (La Negresse), Armory Show catalogue photo

-

Antoine Bourdelle, 1910–12, La Musique, bas-relief, Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, Paris

-

Salon des Indépendants, 1913, Paris

-

Amedeo Modigliani, Female Head, 1911/1912, Tate. Paul Guillaume, introduced Modigliani to Constantin Brâncuși. He was Brâncuși's disciple for a year.[20][21]

-

Otto Gutfreund, Violoncelliste (Cellist), 1912–13[22]

-

Musée national d'art moderne, Paris

-

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, 1914, Boy with a Coney (Boy with a rabbit), marble

-

Joseph Csaky, Tête, ca.1920 (front and side view), limestone, 60 cm, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands

-

Aristide Maillol, The Night, 1920, Stuttgart

-

Jacob Epstein, Day and Night, carved for the London Underground's headquarters, 1928.

-

Käthe Kollwitz, The Grieving Parents, 1932, World War I memorial (for her son Peter), Vladslo German war cemetery

-

Jacques Lipchitz, Birth of the Muses, (1944–1950)

-

Barbara Hepworth, Monolith-Empyrean, 1953

-

Alexander Calder, Red Mobile, 1956, Painted sheet metal and metal rods, Montreal Museum of Fine Arts

-

Ruth Asawa, Untitled (1950s-60s; exact date unknown) at the DeYoung Museum in San Francisco.

-

Washington, DC.

-

Chicago, Illinois

-

Berlin, Germany, Rickey is considered a Kinetic sculptor

-

Alexander Calder, Crinkly avec disc rouge, 1973, Schlossplatz, Stuttgart

-

Louise Nevelson, Atmosphere and Environment XII, 1970–1973, Philadelphia Museum of Art

-

Sir Anthony Caro, Black Cover Flat, 1974, steel, Tel Aviv Museum of Art

-

Jean-Yves Lechevallier, Cristaux, Homage to Béla Bartók, Paris, 1980

-

Barcelona, Spain

-

Iron: Man, 2005, in Victoria Square, Birmingham

-

Yayoi Kusama, Pumpkin, 2015, in Montreal.

-

Karen LaMonte, Etudes, 2017, at the Hunter Museum of Art in Tennessee.

Contemporary movements

Also during the 1960s and 1970s artists as diverse as

Conceptual art is art in which the concept(s) or idea(s) involved in the work take precedence over traditional aesthetic and material concerns. Works include One and Three Chairs, 1965, by Joseph Kosuth, and An Oak Tree, 1973, by Michael Craig-Martin, and those of Joseph Beuys and James Turrell among others.[25]

- Site-Construction: the intersection of landscape and architecture

- Axiomatic Structures: the combination of architecture and not-architecture

- Marked sites: the combination of landscape and not-landscape

- Sculpture: intersection of not-landscape and not-architecture

-

Spiral Jetty by Robert Smithson from atop Rozel Point, in mid-April 2005

-

Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Umbrellas 1991, (Japan) [26]

-

Richard Long, South Bank Circle, 1991 Tate Liverpool, England

-

Time guards / Madonna,light sculpture by Manfred Kielnhofer at the Light Art Biennale Austria 2010

Minimalism

-

Tony Smith, Free Ride, 1962, Museum of Modern Art

-

Larry Bell, Untitled 1964, bismuth, chromium, gold, and rhodium on gold-plated brass; Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden

-

Donald Judd, Untitled 1977, Münster

-

Cor-ten steel near Liverpool Street station

-

Donald Judd, Untitled, 1991, Israel Museum Art Garden

Postminimalism

-

Anish Kapoor, Turning the World Upside Down, Israel Museum, 2010

-

The Spire of Dublin officially titled the Monument of Light, stainless steel, 121.2 metres (398 ft), the world's tallest sculpture

Contemporary genres

Modern sculpture is often created outdoors, as in

See also

- List of female sculptors

- List of sculptors

- Outline of sculpture

- List of most expensive sculptures

- National Gallery of Art Sculpture Garden

- Arborsculpture

- Assemblage

- Butter sculpture

- Bricolage

- California Clay Movement

- Collage

- Cubist sculpture

- Decollage

- Environmental art

- Earthworks (art)

- Electrotyping

- Floral design (Ikebana)

- Garden sculpture

- Gas sculpture

- Glassblowing

- Hologram

- Kinetic sculpture

- Land art (Earth art)

- Land Arts of the American West

- Light sculpture

- Living sculpture

- Mask

- Mobiles

- Neon lighting and artists in light

- Origami

- Plaster cast

- Site-specific art

- Sustainable art

- Wax sculpture

- Welded sculpture

- Welding

References

- ^ "The Burghers of Calais, (sculpture)". SIRIS

- ISBN 0-19-513381-1.

- ^ "Rodin to Now: Modern Sculpture", Palm Springs Desert Museum.

- ^ Giedion-Welcker, Carola, ‘’Contemporary Sculpture: An Evolution in Volume and Space, A revised and Enlarged Edition’’, Faber and Faber, London, 1961, p. X

- ^ Atkins, Robert, ‘’ARTSPOKE: A Guide to Modern Ideas, Movements and Buzzwords, 1848-1944’’ Abbeville Publishers, New York, 1993, p.140

- ^ Curtis, Penelope, ‘’Sculpture: 1900-1945’’, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1999, p. 1

- ^ Elsen, Albert L., ‘’Rodin’s Gates of Hell’’, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, MN, 1960 p. 77

- ^ Grace Glueck, "Picasso Revolutionized Sculpture Too", New York Times, exhibition review 1982, Retrieved July 20, 2010.

- ^ "Gallery".

- ^ Robert Rosenblum, "Cubism", Readings in Art History 2 (1976), Seuphor, Sculpture of this Century

- ^ Edith Balas, Joseph Csaky: A Pioneer of Modern Sculpture, American Philosophical Society, 1998.

- ISBN 978-0-8109-3934-9

- ^ "Constantin Brâncuși", Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition, 2008 http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/Constantin_Brancusi.aspx

- ISBN 978-0-19-512878-9

- ^ National Air and Space Museum Receives "Ascent" Sculpture for display at Udvar-Hazy Center [1][permanent dead link]

- ^ The Guardian, Hillary Spurling on The Back Series

- ^ MoMA, the collection

- ^ Tate

- ^ Rodin Museum, The Three Shades

- ^ the Art Story

- ^ Klein, Mason, et al., Modigliani: Beyond the Myth. The Jewish Museum and Yale University Press, 2004.

- ^ Otto Gutfreund - exhibition in the Municipal House (Czech Radio)

- ^ Guggenheim museum Archived 2013-01-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Dia Foundation

- ^ Tate

- ^ NY Times, Umbrella Crushes Woman

- ^ Peter Frank, "Site Sculpture", Art News, Oct. 1975

- ^ Catherine Howett, New Directions in Environmental Art, Landscape Architecture, Jan. 1977

- ^ Lucy Lippard, Art Outdoors, In and Out of the Public Domain, Studio International, March–April 1977

- ^ "Art Army by Michael Leavitt", hypediss.com [2], December 13, 2006.

External links

- Article on Minimalist Art at the Dia Beacon Museum"Dia Beacon", Tiziano Thomas Dossena, Bridge Apulia USA N.9, 2003

- Tate, Definition of Minimal Art

- Tate Glossary: Minimalism

- MoMA, Art terms Minimalism

- Modern Sculpture and the Question of Status (Ebook), edited by C. Rodriguez-Samaniego and I. Gras Valero, University of Barcelona, 2018

![Auguste Rodin, The Three Shades, before 1886, plaster, 97 x 91.3 x 54.3 cm. In Dante's Divine Comedy, the shades, i.e. the souls of the damned, stand at the entrance to The Gates of Hell, pointing to an unequivocal inscription, “Abandon hope, all ye who enter here”. Rodin assembled three identical figures that seem to be turning around the same point.[19]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/fe/Auguste_Rodin%2C_The_three_shades_%28Les_Trois_Ombres%29%2C_for_the_top_of_The_Gates_of_Hell%2C_before_1886%2C_plaster.jpg/188px-Auguste_Rodin%2C_The_three_shades_%28Les_Trois_Ombres%29%2C_for_the_top_of_The_Gates_of_Hell%2C_before_1886%2C_plaster.jpg)

![Amedeo Modigliani, Female Head, 1911/1912, Tate. Paul Guillaume, introduced Modigliani to Constantin Brâncuși. He was Brâncuși's disciple for a year.[20][21]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/23/Modis2.jpg/105px-Modis2.jpg)

![Otto Gutfreund, Violoncelliste (Cellist), 1912–13[22]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/7d/Otto_Gutfreund%2C_Violoncelliste%2C_c._1912-13.jpg/122px-Otto_Gutfreund%2C_Violoncelliste%2C_c._1912-13.jpg)

![Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Umbrellas 1991, (Japan) [26]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5a/Umbrella_Project1991_10_27.jpg/200px-Umbrella_Project1991_10_27.jpg)