Acanthamoeba

| Acanthamoeba | |

|---|---|

| |

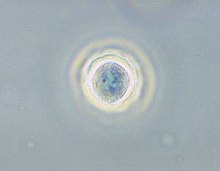

| Phase contrast micrograph of an Acanthamoeba polyphaga cyst. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Phylum: | Amoebozoa |

| Class: | Discosea |

| Order: | Centramoebida

|

| Family: | Acanthamoebidae |

| Genus: | Acanthamoeba Volkonsky 1931 |

| Type species | |

| Acanthamoeba castellanii Volkonsky 1931

| |

Acanthamoeba is a genus of

Distribution

Acanthamoeba spp. are among the most prevalent protozoa found in the environment.[1] They are distributed worldwide, and have been isolated from soil, air, sewage, seawater, chlorinated swimming pools, domestic tap water, bottled water, dental treatment units, hospitals, air-conditioning units, and contact lens cases. Additionally, they have been isolated from human skin, nasal cavities, throats, and intestines, as well as plants and other mammals.[2]

Role in disease

Diseases caused by Acanthamoeba include keratitis and granulomatous amoebic encephalitis (GAE).[3] The latter is often but not always seen in immunosuppressed patients.[4] GAE is caused by the amoebae entering the body through an open wound and then spreading to the brain.[5] The combination of host immune responses and secreted amoebal proteases causes massive brain swelling[6] resulting in death in about 95% of those infected.

Granulomatous amoebic encephalitis (GAE)

Granulomatous amoebic encephalitis (GAE) is caused by amoebic infection of the central nervous system (CNS). It is characterized by

Infection usually mimics that of bacterial

Acanthamoebic keratitis

When present in the eye, Acanthamoeba strains can cause acanthamoebic keratitis, which may lead to corneal ulcers or even blindness.[10] This condition occurs most often among contact lens wearers who do not properly disinfect their lenses, exacerbated by a failure to wash hands prior to handling the lenses. Multipurpose contact lens solutions are largely ineffective against Acanthamoeba, whereas hydrogen peroxide-based solutions have good disinfection characteristics.[11][12]

The first cure of a corneal infection was achieved in 1985 at Moorfields Eye Hospital.[13]

In May 2007, Advanced Medical Optics, manufacturer of Complete Moisture Plus Contact Lens Solution products, issued a voluntary recall of their Complete Moisture Plus solutions. The fear was that contact lens wearers who used their solution were at higher risk of acanthamoebic keratitis than contact lens wearers who used other solutions. The manufacturer recalled the product after the

As a bacterial reservoir

Several species of bacteria that can cause human disease are also able to infect and replicate within Acanthamoeba species.[1] These include Legionella pneumophila, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and some strains of Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus.[1][15] For some of these bacteria, replication inside Acanthamoeba has been associated with enhanced growth in macrophages, and increased resistance to some antibiotics.[1] Furthermore, due to the high prevalence of Acanthamoeba in the environment, these amoebae have been proposed to serve as an environmental reservoir for some human pathogens.[1]

Ecology

A. castellanii can be found at high densities in various soil ecosystems. It preys on bacteria, but also fungi and other protozoa.

This species is able to lyse bacteria and produce a wide range of enzymes, such as cellulases or chitinases,[16] and probably contributes to the breakdown of organic matter in soil, contributing to the microbial loop.

Physiology

Role as a model organism

Because Acanthamoeba does not differ greatly at the ultrastructural level from a mammalian cell, it is an attractive model for cell-biology studies; it is important in cellular microbiology, environmental biology, physiology, cellular interactions, molecular biology, biochemistry, and evolutionary studies, due to the organisms' versatile roles in the ecosystem and ability to capture prey by

The recently available Acanthamoeba genome sequence revealed several orthologs of genes employed in meiosis of sexual eukaryotes. These genes included Spo11, Mre11, Rad50, Rad51, Rad52, Mnd1, Dmc1, Msh, and Mlh.[19] This finding suggests that Acanthamoeba is capable of some form of meiosis and may be able to undergo sexual reproduction. Furthermore, since Acanthamoeba diverged early from the eukaryotic family tree, these results suggest that meiosis was present early in eukaryotic evolution.

Owing to its ease and economy of cultivation, the Neff strain of A. castellanii, discovered in a pond in

Endosymbionts

Acanthamoeba spp. contain diverse bacterial endosymbionts that are similar to human pathogens, so they are considered to be potential emerging human pathogens.[23] The exact nature of these symbionts and the benefit they represent for the amoebic host still have to be clarified. These include Legionella and Legionella-like pathogens.[24]

Giant viruses

The

Members of the genus Acanthamoeba are unusual in serving as hosts for a variety of

Diversity

Acanthamoeba can be distinguished from other genera of amoebae based on morphological characteristics.

Below is a list of described species of Acanthamoeba, with sequence types noted where known. Species that have been identified in diseased patients are marked with *.

- A. astronyxis (Ray & Hayes 1954) Page 1967 * (T7)

- A. byersi Qvarnstrom, Nerad & Visvesvara 2013 *

- A. castellanii Volkonski 1931 * (T4) [A. terricola Pussard 1964]

- A. comandoni Pussard 1964 (T9)

- A. culbertsoni (Singh & Das 1970) Griffin 1972 * (T10)

- A. divionensis Pussard & Pons 1977 (T4)

- A. echinulata Pussard & Pons 1977

- A. gigantea Schmöller 1964

- A. glebae (Dobell 1914)

- A. gleichenii Volkonsky 1931

- A. griffini Sawyer 1971 (T3)

- A. hatchetti Sawyer, Visvesvara & Harke 1977 * (T11)

- A. healyi Moura, Wallace & Visvesvara 1992 (T12)

- A. hyalina Dobel & O'connor 1921

- A. jacobsi Sawyer, Nerad & Visvesvara 1992

- A. keratitis *

- A. lenticulata Molet & Ermolieff-braun 1976 (T3)

- A. lugdunensis Pussard & Pons 1977 * (T4)

- A. mauritaniensis Pussard & Pons 1977 (T4)

- A. micheli Corsaro et al. 2015

- A. palestinensis (Reich 1933) Page 1977 * (T1)

- A. paradivionensis Pussard & Pons 1977 (T4)

- A. pearcei Nerad et al. 1995

- A. polyphaga (Puschkarew 1913) Volkonsky 1931 * (T4)

- A. pustulosa Pussard & Pons 1977 (T2)

- A. pyriformis (Olive & Stoianovitch 1969) Spiegel & Shadwick 2016

- A. quina Pussard & Pons 1977 *

- A. rhysodes (Singh 1952) Griffin 1972 * (T4)

- A. royreba Willaert, Stevens & Tyndall 1978

- A. sohi Kyung-il & Shin 2003

- A. stevensoni Sawyer et al. 1993 (T11)

- A. triangularis Pussard & Pons 1977 (T4)

- A. tubiashi Lewis & Sawyer 1979 (T8)

Etymology

From the Greek akantha (spike/thorn), which was added before "amoeba" (change) to describe this organism as having a spine-like structure (acanthopodia). This organism is now well known as Acanthamoeba, an amphizoic, opportunistic, and nonopportunistic protozoan protist widely distributed in the environment.[27]

See also

References

- ^ PMID 12692099.

- PMID 2047667.

- PMID 1456885.

- ^ S2CID 28069984.

- ^ PMID 23669391.

- PMID 25930186.

- PMID 17207487.

- PMID 18445961.

- PMID 24509420.

- PMID 25687209.

- S2CID 54503941.

- PMID 19403771.

- PMID 4052364.

- ^ "Abbott Medical Optics" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 31 May 2009.

- PMID 18399997.

- PMID 16171187.

- ISBN 978-1-904455-43-1.

- ^ Baig AM, Khan NA, Abbas F. Eukaryotic cell encystation and cancer cell dormancy: is a greater devil veiled in the details of a lesser evil? Cancer Biol

- PMID 25800982.

- S2CID 5234123.

- PMID 28506204.

- PMID 29058403.

- S2CID 21052932.

- PMID 15072770.

- S2CID 16877147.

- ^ PMID 19885332.

- PMC 7392430.

citing public domain text from the CDC

External links

- Acanthamoeba – Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- Video of Acanthamoeba from contact lens keratitis

- Marciano-Cabral F, Cabral G (April 2003). "Acanthamoeba spp. as agents of disease in humans". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 16 (2): 273–307. PMID 12692099.

- Comprehensive resource on Amoeba

- Eye health and Acanthamoeba

- Acanthamoeba pictures and illustrations