Aconitum

| Aconitum | |

|---|---|

| |

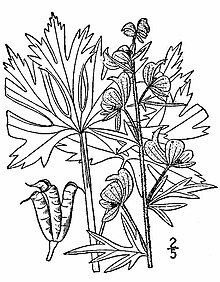

| Aconitum variegatum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Order: | Ranunculales |

| Family: | Ranunculaceae |

| Subfamily: | Ranunculoideae |

| Tribe: | Delphinieae |

| Genus: | Aconitum L. |

| Subgenera[1] | |

| |

Aconitum (

Most Aconitum species are extremely poisonous and must be handled very carefully.[3][5] Several Aconitum hybrids, such as the Arendsii form of Aconitum carmichaelii, have won gardening awards—such as the Royal Horticultural Society's Award of Garden Merit.[6] Some are used by florists.[7]

Etymology

The name aconitum comes from the Greek word ἀκόνιτον, which may derive from the Greek akon for dart or javelin, the tips of which were poisoned with the substance, or from akonae, because of the rocky ground on which the plant was thought to grow.[8] The Greek name lycoctonum, which translates literally to "wolf's bane", is thought to indicate the use of its juice to poison arrows or baits used to kill wolves.[9] The English name monkshood refers to the cylindrical helmet, called the galea, distinguishing the flower.[4]

Description

The dark green leaves of Aconitum species lack

The tall, erect stem is crowned by

The fruit is an aggregate of follicles, a follicle being a dry, many-seeded structure.

Unlike with many species from genera (and their hybrids) in Ranunculaceae (and the related Papaveroideae subfamily), there are no double-flowered forms.

Color range

A medium to dark semi-saturated blue-purple is the typical flower color for Aconitum species. Aconitum species tend to be variable enough in form and color in the wild to cause debate and confusion among experts when it comes to species classification boundaries. The overall color range of the genus is rather limited, although the palette has been extended a small amount with hybridization. In the wild, some Aconitum blue-purple shades can be very dark. In cultivation the shades do not reach this level of depth.

Aside from blue-purple—white, very pale greenish-white, creamy white, and pale greenish-yellow are also somewhat common in nature. Wine red (or red-purple) occurs in a hybrid of the climber Aconitum hemsleyanum. There is a pale semi-saturated pink produced by cultivation as well as bicolor hybrids (e.g. white centers with blue-purple edges). Purplish shades range from very dark blue-purple to a very pale lavender that is quite greyish. The latter occurs in the "Stainless Steel" hybrid.

Neutral blue (rather than purplish or greenish), greenish-blue, and intense blues, available in some related

Monkshood (Aconitum napellus) produces light indigo-blue flowers,[10] while Wolf's Bane (Aconitum vulparia) produces whitish or straw-yellow flowers.[11]

Horticultural trade morphology

The lack of double-flowered forms in the horticultural trade stands in contrast with the other genera of

Ecology

Aconitum species have been recorded as food plant of the caterpillars of several

Aconitum flowers are pollinated by long-tongued bumblebees.[17] Bumblebees have the strength to open the flowers and reach the single nectary at the top of the flower on its inside.[17] Some short-tongued bees will bore holes into the tops of the flowers to steal nectar.[17] However, alkaloids in the nectar function as a deterrent for species unsuited to pollination. The effect is greater in certain species, such as Aconitum napellus, than in others, such as Aconitum lycoctonum.[18] Unlike the species with blue-purple flowers such as A. napellus, A. lycoctonum—which has off-white to pale yellow flowers, has been found to be a nectar source for butterflies.[17] This is likely due to the nectary flowers of the latter being more easily reachable by the butterflies; however, the differing alkaloid character of the two plants may also play a significant role or be the primary influence.[17]

Cultivation

The species typically utilized by gardeners fare well in well-drained evenly moist "humus-rich" garden soils like many in the related

Award-winning hybrids

In the UK, the following have gained the Royal Horticultural Society's Award of Garden Merit:

- A. × cammarum 'Bicolor'[19]

- A. carmichaelii 'Arendsii'[20]

- A. carmichaelii 'Kelmscott' [21]

- A. 'Bressingham Spire'[22]

- A. 'Spark's Variety'[23][24]

- A. 'Stainless Steel'[25]

Toxicology

Monkshood and other members of the genus Aconitum contain substantial amounts of the highly toxic aconitine and related alkaloids, especially in their roots and tubers.[3] As little as 2 mg of aconite or 1 g of plant may cause death from respiratory paralysis or heart failure.[3]

Aconitine is a potent

Marked symptoms may appear almost immediately, usually not later than one hour, and "with large doses death is almost instantaneous". Death usually occurs within two to six hours in fatal poisoning (20 to 40 mL of

Treatment of poisoning is mainly supportive. All patients require close monitoring of

Mild toxicity (headache, nausea and palpitations) as well as severe toxicity may be experienced from skin contact.[30] Paraesthesia, including tingling and feelings of coldness in the face and extremities, is common in reports of toxicity.[31]

Uses

Folk medicine

Aconite was described in Greek and Roman

Aconitum chasmanthum is listed as critically endangered,[34] Aconitum heterophyllum as endangered,[35] and Aconitum violaceum as vulnerable due to overcollection for use as an herbal medicine.[36]

A producer of Yunnan Baiyao, a traditional Chinese medicine remedy, has disclosed the remedy contains aconite.[37]

As a poison

The roots of A. ferox supply the

Several species of Aconitum have been used as arrow poisons. The

armed with a poison-tipped lance would hunt the whale, paralyzing it with the poison and causing it to drown.It has, albeit rarely, been hypothesized that Socrates was executed via an extract from an Aconitum species, such as Aconitum napellus, rather than via hemlock, Conium maculatum. Aconitum was commonly used by the ancient Greeks as an arrow poison but can be used for other forms of poisoning. It has been hypothesized that Alexander the Great and Ptolemy XIV Philopator were murdered via aconite.[43]

In 1524, in the first recorded

In April 2021, the president of Kyrgyzstan, Sadyr Japarov, promoted aconite root as a treatment for COVID-19. Subsequently, at least four people were admitted to hospital suffering from poisoning.[45] Facebook had previously removed the President's posts advocating use of the substance, saying "We've removed this post as we do not allow anyone, including elected officials, to share misinformation that could lead to imminent physical harm or spread false claims about how to cure or prevent COVID-19".[46]

Taxonomy

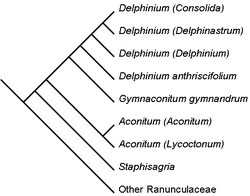

Genetic analysis suggests that Aconitum as it was delineated before the 21st century is nested within

Species

- Aconitum ajanense

- Aconitum albo-violaceum

- Aconitum altaicum

- Aconitum ambiguum

- Aconitum angusticassidatum

- Aconitum anthora (yellow monkshood)

- Aconitum anthoroideum

- Aconitum album

- Aconitum axilliflorum

- Aconitum baburinii

- Aconitum baicalense

- Aconitum barbatum

- Aconitum besserianum

- Aconitum biflorum

- Aconitum bucovinense

- Aconitum burnatii

- Aconitum carmichaelii (Carmichael's monkshood)

- Aconitum charkeviczii

- Aconitum chasmanthum

- Aconitum chinense Siebold.&Zucc.[48] aka Aconitum carmichaelii var. truppelianum

- Aconitum cochleare

- Aconitum columbianum (western monkshood)

- Aconitum confertiflorum

- Aconitum consanguineum

- Aconitum coreanum

- Aconitum crassifolium

- Aconitum cymbulatum

- Aconitum czekanovskyi

- Aconitum decipiens

- Aconitum degenii (syn. A. variegatum ssp. paniculatum)

- Aconitum delphinifolium (larkspurleaf monkshood)

- Aconitum desoulavyi

- Aconitum ferox (Indian aconite)

- Aconitum firmum

- Aconitum fischeri (Fischer monkshood)

- Aconitum flavum (Fluff iron hammer)

- Aconitum flerovii

- Aconitum gigas

- Aconitum gracile (synonym of A. variegatum ssp. variegatum)

- Aconitum helenae

- Aconitum hemsleyanum (climbing monkshood)

- Aconitum henryi (Sparks variety monkshood)

- Aconitum heterophyllum

- Aconitum hosteanum

- Aconitum infectum (Arizona monkshood)

- Aconitum jacquinii (synonym of A. anthora)

- Aconitum jaluense

- Aconitum japonicum

- Aconitum jenisseense

- Aconitum karafutense

- Aconitum karakolicum

- Aconitum kirinense

- Aconitum koreanum

- Aconitum krylovii

- Aconitum kunasilense

- Aconitum kurilense

- Aconitum kusnezoffii (Kusnezoff monkshood)

- Aconitum kuzenevae

- Aconitum lamarckii

- Aconitum lasiostomum

- Aconitum lethale (formerly A. balfourii)

- Aconitum leucostomum

- Aconitum longiracemosum

- Aconitum lycoctonum (northern wolfsbane)

- Aconitum macrorhynchum

- Aconitum maximum (Kamchatka aconite)

- Aconitum miyabei

- Aconitum moldavicum

- Aconitum montibaicalense

- Aconitum nanum

- Aconitum napellus (monkshood; type species)

- Aconitum nasutum

- Aconitum nemorum

- Aconitum neosachalinense

- Aconitum noveboracense (northern blue monkshood)

- Aconitum ochotense

- Aconitum orientale

- Aconitum paniculatum

- Aconitum paradoxum

- Aconitum pascoi

- Aconitum pavlovae

- Aconitum pilipes

- Aconitum plicatum

- Aconitum podolicum

- Aconitum productum

- Aconitum pseudokusnezowii

- Aconitum puchonroenicum

- Aconitum raddeanum

- Aconitum ranunculoides

- Aconitum reclinatum (trailing white monkshood)

- Aconitum rogoviczii

- Aconitum romanicum

- Aconitum rotundifolium

- Aconitum rubicundum

- Aconitum sachalinense

- Aconitum sajanense

- Aconitum saxatile

- Aconitum sczukinii

- Aconitum septentrionale

- Aconitum seravschanicum

- Aconitum sichotense

- Aconitum smirnovii

- Aconitum soongaricum

- Aconitum stoloniferum

- Aconitum stubendorffii

- Aconitum subalpinum

- Aconitum subglandulosum

- Aconitum subvillosum

- Aconitum sukaczevii

- Aconitum taigicola

- Aconitum talassicum

- Aconitum tanguticum

- Aconitum tauricum

- Aconitum turczaninowii

- Aconitum umbrosum

- Aconitum uncinatum (southern blue monkshood)

- Aconitum variegatum

- Aconitum violaceum

- Aconitum volubile

- Aconitum vulparia (wolf's bane)

- Aconitum woroschilovii

Natural hybrids

- Aconitum × austriacum

- Aconitum × cammarum

- Aconitum × hebegynum

- Aconitum × oenipontanum (A. variegatum ssp. variegatum × ssp. paniculatum)

- Aconitum × pilosiusculum

- Aconitum × platanifolium (A. ycoctonum ssp. neapolitanum × ssp. vulparia)

- Aconitum × zahlbruckneri (A. napellus ssp. vulgare × A. variegatum ssp. variegatum)

As a poison

Aconite has been understood as a poison from ancient times, and is frequently represented as such in fiction. In

As a well-known poison from ancient times, aconite is well-suited for historical fiction. It is the poison used by a murderer in the third of

Aconite also lends itself to use as a fictional poison in modern settings. An overdose of aconite was the method by which Rudolph Bloom, father of Leopold Bloom in James Joyce's Ulysses, committed suicide.

Wolf's bane

In his mythological poem Metamorphoses, Ovid tells how the herb comes from the slavering mouth of Cerberus, the three-headed dog that guarded the gates of Hades.[54] In his Natural History, Pliny the Elder supports the legend that aconite came from the saliva of the dog Cerberus when Hercules dragged him from the underworld.[55] As the veterinary historian John Blaisdell has noted, symptoms of aconite poisoning in humans bear some passing similarity to those of rabies: frothy saliva, impaired vision, vertigo, and finally a coma. Thus, some ancient Greeks possibly would have believed that this poison, mythically born of Cerberus's lips, was literally the same as that to be found inside the mouth of a rabid dog.[56]

In John Keats's poem Ode to Melancholy, wolf's bane is mentioned in the first verse as the source of "poisonous wine", possibly referring to Medea.

In the 1931 classic horror film

In the 1941 film The Wolf Man starring Lon Chaney Jr. and Claude Rains, the following poem is recited several times Even a man who is pure in heart and says his prayers by night, may become a wolf when the wolf-bane blooms and the autumn moon is bright.[58]

In the 1943 French novel Our Lady of the Flowers, the boy Culafroy eats "Napel aconite", so that the "Renaissance would take possession of the child through the mouth."[59]

In the TV-show Game of Thrones, one of Tywin Lannister's commanders is assassinated by a dart, identified by Tywin as Wolf's Bane, due to its scent.

In the early 1980s, famed Spanish horror film star Paul Naschy named his production company "Aconito Films", an in-joke relating to the large number of werewolf movies he produced.

In mysticism

Wolf's bane is used as an analogy for the power of divine communion in Liber 65 1:13–16, one of

Gallery

-

Trailing white monkshood (A. reclinatum)

-

Southern blue monkshood (A. uncinatum)

-

Wild Alaskan monkshood (A. delphinifolium) is a flowering species that belongs to the family Ranunculaceae. The picture was taken in Kenai National Wildlife Refuge in Alaska.

See also

- Rufus T. Bush, industrial tycoon who died of accidental aconite poisoning

References

- ^ PMID 22182994.

- ^ Sunset Western Garden Book, 1995:606–607

- ^ a b c d "Aconite". Drugs.com. 2023. Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Aconite". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 151–152.

- ^ Hay, R. (Consultant Editor) second edition 1978. Reader's Digest Encyclopedia of Garden Plants and Flowers. The Reader's Digest Association Limited.

- ^ "Aconitum carmichaelii var arendsii". Cambridge University Botanic Garden. Cambridge University. 2019. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- ^ Buchan, Ursula (25 June 2015). "How to grow: Monkshood". The Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group Limited. Archived from the original on 2022-01-12. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- ^ "Aconite Poisoning". Penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- ^ "A Modern Herbal | Aconite Herb". botanical.com. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ISBN 0-86318-386-7.

- ISBN 0-86318-386-7.

- ^ Bellmann, Heiko (2003). Der neue Kosmos Schmetterlingsführer. Stuttgart: Franckh-Kosmos Verlags GmbH.

- doi:10.5519/havt50xw.

- ^ "Atlas Hymenoptera - Atlas of the European Bees - STEP project". atlashymenoptera.net. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ISBN 9780226874005. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ^ Rasmont, Pierre (2014). "Atlas of the European Bees: genus Bombus". Atlas Hymenoptera. Université de Mons. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Blanché, César; Bosch, Maria; Molero, Juliá; Simon, Joan (1997). "Pollination Ecology In Tribe Delphineae (Ranunculaceae) in W Mediterranean Area: Floral Visitors And Pollinator Behavior" (PDF). Lagascalia. 19 (1–2): 545–562. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- S2CID 9657915. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- ^ "RHS Plant Selector - Aconitum × cammarum 'Bicolor'". Retrieved 23 February 2020.

- ^ "Aconitum carmichaelii (Arendsii Group) 'Arendsii'". RHS. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- ^ "Aconitum carmichaelii (Wilsonii Group) 'Kelmscott'". RHS. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- ^ "Aconitum 'Bressingham Spire'". Royal Horticultural Society. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- ^ "Aconitum 'Spark's Variety'". Royal Horticultural Society. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- ^ Bourne, Val (31 July 2009). "How to grow: Aconitum 'Sparks Variety'". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 2022-01-12. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ "Aconitum 'Stainless Steel'". RHS. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- ^ a b The Extra Pharmacopoeia Martindale. Vol. 1, 24th edition. London: The Pharmaceutical Press, 1958, page 38.

- ^ S2CID 2697673.

- S2CID 218856921.

- PMID 15111916.

- PMID 22766196.

- S2CID 2697673.

- .

- PMID 28789666.

- ^ "Aconitum chasmanthum". Iucnredlist.org. 2014-07-18. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- ^ "Aconitum heterophyllum". Iucnredlist.org. 2014-07-18. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- ^ "Aconitum violaceum". Iucnredlist.org. 2014-07-18. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- ^ "Should Recipes for Chinese Medicine Be Open? -- Beijing Review". www.bjreview.com.cn. Retrieved 2024-03-13.

- ^ Peissel, Michel. 1984. The Ants' Gold. The Discovery of the Greek El Dorado in the Himalayas. London, Harvill Press, pp. 99–100.

- ^ Sung, Ying-hsing. T'ien kung k'ai wu. Sung Ying-hsing. 1637. Published as Chinese Technology in the Seventeenth Century. Translated and annotated by E-tu Zen Sun and Shiou-chuan Sun. 1996. Mineola. New York. Dover Publications, p. 267.

- ^ Chavannes, Édouard. "Trois Généraux Chinois de la dynastie des Han Orientaux. Pan Tch'ao (32-102 p.C.); – son fils Pan Yong; – Leang K'in (112 p.C.). Chapitre LXXVII du Heou Han chou.". 1906. T'oung pao 7, pp. 226–227.

- . Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- )

- )

- .

- ^ "Four Patients Being Treated In Kyrgyz Hospitals For Poisoning With Toxic Root Promoted By President". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 22 April 2021.

- ^ "Facebook Removes Kyrgyz President's Post Promoting Toxic Root To Fight COVID". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 19 April 2021.

- doi:10.12705/624.10. Archived from the original(PDF) on 23 February 2014. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ^ "Aconitum chinense - Plants for a Future database report". Archived from the original on 2009-01-15. Retrieved 2009-09-10.

- ISBN 0486227987.

- ^ More, Brookes (1922). "P. Ovidius Naso : Metamorphoses; Book 6, lines 87–145". Perseus Digital Library Project. Boston: Cornhill Publishing Co.

- ISBN 0-14-001026-2.

- ^ "附子 in English - Japanese-English Dictionary | Glosbe". en.glosbe.com.

- ISBN 9780231108737.

- ^ Ovid, Metamorphoses 7.406 ff.. The story is first attested by Euphorion of Chalcis, fragment 41 Lightfoot (Lightfoot, pp. 272–275).

- ^ the Elder, Pliny. "Chapter 2. Aconite, Otherwise Called Thelyphonon, Cammaron, Pardalianches, or Scorpio; Four Remedies.". The Natural History of Pliny, Book XXVII. Translated by Bostock, John; Riley, Henry T. p. 218.

- ^ Rabid: a Cultural History of the World's Most Diabolical Virus by Bill Wasik.

- ^ Kuehl, BJ. "Count Dracula Original Movie Script". Script-o-rama.com. Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- ^ "The Wolf Man, Quotes". IMDb.com. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- ^ p. 136, Our Lady of the Flowers by Jean Genet, tr. Bernard Frechtman, Grove Press, NYC, 1961

External links

- James Grout: Aconite Poisoning, part of the Encyclopædia Romana

- Photographs of Aconite plants

- Jepson Eflora entry for Aconitum