Acute coronary syndrome

| Acute coronary syndrome | |

|---|---|

| |

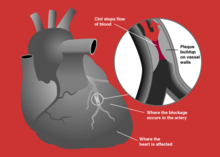

| Blockage of a coronary artery | |

| Specialty | Cardiology |

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is a

Acute coronary syndrome is subdivided in three scenarios depending primarily on the presence of

ACS should be distinguished from

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms of the acute coronary syndromes are similar.

In unstable angina, symptoms may appear on rest or on minimal exertion.

Though ACS is usually associated with coronary thrombosis, it can also be associated with cocaine use.[11] Chest pain with features characteristic of cardiac origin (angina) can also be precipitated by profound anemia, brady- or tachycardia (excessively slow or rapid heart rate), low or high blood pressure, severe aortic valve stenosis (narrowing of the valve at the beginning of the aorta), pulmonary artery hypertension and a number of other conditions.[12]

Pathophysiology

In those who have ACS,

Other, less common, causes of acute coronary syndrome include spontaneous coronary artery dissection,[14] ischemia in the absence of obstructive coronary artery disease (INOCA), and myocardial infarction in the absence of obstructive coronary artery disease (MINOCA).[15]

Diagnosis

Electrocardiogram

In the setting of acute chest pain, the

Blood tests

Change in levels of

Prediction scores

A combination of cardiac biomarkers and risk scores, such as HEART score and TIMI score, can help assess the possibility of myocardial infarction in the emergency setting.[19][13]

Prevention

Acute coronary syndrome often reflects a degree of damage to the coronaries by

After a ban on smoking in all enclosed public places was introduced in Scotland in March 2006, there was a 17% reduction in hospital admissions for acute coronary syndrome. 67% of the decrease occurred in non-smokers.[21]

Treatment

People with presumed ACS are typically treated with aspirin,

STEMI

If the ECG confirms changes suggestive of

NSTEMI and NSTE-ACS

If the ECG does not show typical changes consistent with STEMI, the term "non-ST segment elevation ACS" (NSTE-ACS) may be used and encompasses "non-ST elevation MI" (NSTEMI) and unstable angina.

The accepted management of unstable angina and acute coronary syndrome is therefore empirical treatment with aspirin, a second

If there is no evidence of ST segment elevation on the

Prognosis

Prediction scores

The TIMI risk score can identify high risk patients in ST-elevation and non-ST segment elevation MI ACS[30][31] and has been independently validated.[32][33]

Based on a global registry of 102,341 patients, the GRACE risk scoreestimates in-hospital, 6 months, 1 year, and 3-year mortality risk after a heart attack.[34] It takes into account clinical (blood pressure, heart rate, EKG findings) and medical history.[34] Nowadays, GRACE risk score is also used within non-ST elevation ACS patients as a high-risk criteria(GRACE score > 140), which may favor early invasive strategy within 24 hours of the heart attack.[35]

Biomarkers

The aim of prognostic markers is to reflect different components of pathophysiology of ACS. For example:[citation needed]

- Natriuretic peptide – both B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) and N-terminal proBNP can be applied to predict the risk of death and heart failure following ACS.

- Monocyte chemo attractive protein (MCP)-1 – has been shown in a number of studies to identify patients with a higher risk of adverse outcomes after ACS.

Coronary CT angiography combined with troponin levels is also helpful to triage those who are susceptible to ACS. F-fluoride positron emission tomography is also helpful in identifying those with high risk, lipid-rich coronary plaques.[13]

Day of admission

Studies have shown that for ACS patients, weekend admission is associated with higher mortality and lower utilization of invasive cardiac procedures, and those who did undergo these interventions had higher rates of mortality and complications than their weekday counterparts. This data leads to the possible conclusion that access to diagnostic/interventional procedures may be contingent upon the day of admission, which may impact mortality.[36][37] This phenomenon is described as weekend effect.

See also

- Allergic acute coronary syndrome(Kounis syndrome)

References

- ^ PMID 25249585.

- from the original on 5 April 2017.

- PMID 10866870.

- PMID 12791748.

- PMID 17462519.

- ^ PMID 32860058.

Unstable angina is defined as myocardial ischaemia at rest or on minimal exertion in the absence of acute cardiomyocyte injury/necrosis. [...] Compared with NSTEMI patients, individuals with unstable angina do not experience acute cardiomyocyte injury/necrosis.

- PMID 32860030.

NSTEMI is characterized by ischaemic symptoms associated with acute cardiomyocyte injury (=rise and/or fall in cardiac troponin T/I), while ischaemic symptoms at rest (or minimal effort) in the absence of acute cardiomyocyte injury define unstable angina. This translates into an increased risk of death in NSTEMI patients, while unstable angina patients are at relatively low short-term risk of death.

- ^ a b c d "Acute Coronary Syndromes (Heart Attack; Myocardial Infarction; Unstable Angina) - Heart and Blood Vessel Disorders". MSD Manual Consumer Version. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ PMID 34709879.

- ^ "Unstable Angina".

- from the original on 9 October 2007.

- ^ "Chest Pain in the Emergency Department: Differential Diagnosis". The Cardiology Advisor. 20 January 2019. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- ^ PMID 27438381.

- PMID 31275818.

- PMID 30913893.

- PMID 10987628.

- PMID 15336583.

- PMID 26472989.

- PMID 26547467.

- PMID 30423391.

- PMID 18669427.

- ^ PMID 20956226.

- PMID 26472989.

- ^ Blankenship JC, Skelding KA (2008). "Rapid Triage, Transfer, and Treatment with Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for Patients with ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction". Acute Coronary Syndromes. 9 (2): 59–65. Archived from the original on 15 July 2011.

- PMID 19898701.

- PMID 28482804.

- PMID 19724041.

- PMID 25178118.

- PMID 18347214.

- PMID 11044416.

- PMID 10938172.

- PMID 16365321.

- PMID 16934646.

- ^ PMID 17032691.

- ^ "2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes". www.escardio.org. Retrieved 13 February 2024.

- PMID 26950171.

- PMID 17360988.