Architecture of Africa

Like other aspects of the

African architecture in some areas has been influenced by external cultures for centuries, according to available evidence. Western architecture has influenced coastal areas since the late 15th century and is now an important source of inspiration for many larger buildings, particularly in major cities.

African architecture uses a wide range of materials, including thatch, stick/wood, mud, mudbrick, rammed earth, and stone. These material preferences vary by region: North Africa for stone and rammed earth, the Horn of Africa for stone and mortar, West Africa for mud/adobe, Central Africa for thatch/wood and more perishable materials, Southeast and Southern Africa for stone and thatch/wood.

Prehistoric architecture

North Africa

Nile Valley

Central Sahara

Kel Essuf Period

Concealed remnants of dismantled

Round Head Period

At the start of the 10th millennium BP, amid the

Pastoral Period

In the collective memory of

Early architecture

Probably the most famous class of structure in all Africa, the Pyramids of Egypt remain one of the world's greatest early architectural achievements, regardless of practicality and origins in a funerary context. Egyptian architectural traditions also favored the building of vast temple complexes.

Little is known of ancient architecture south and west of the Sahara. Harder to date than the pyramids are the monoliths around the Cross River, which have geometric or human designs. The vast number of Senegambian stone circles is also evidence of an emerging architecture.

North Africa

Likely part of

Algeria

Garamantes

Some of the earliest evidence of original Amazigh (Berber) culture in North Africa has been found in the highlands of the Sahara and dates from the second millennium BC, when the region was much less arid than it is today and when the Amazigh population was most likely in the process of spreading across North Africa.[16]: 15–22 One of the earliest groups for which there are historical records are the Garamantes, who were later mentioned by Herodotus. Numerous archaeological sites associated with them have been found in the Fezzan (in present-day Libya), attesting to the existence of small villages, towns, and tombs. At least one settlement dates from as early as 1000 BC. The structures were initially built in dry stone, but around the middle of the millennium (c. 500 BC) they began to be built with mudbrick instead.[16]: 23 By the second century AD there is evidence of large villas and more sophisticated tombs associated with the aristocracy of this society, in particular at Germa.[16]: 24

Egypt

Ancient Egypt

Nabta Playa

At

Sudan

Nubia

The C-Group culture was related to that of the city of Kerma,[19] which was settled around 2400 BC. It was a walled city containing religious buildings, large circular dwellings, a palace, and well-laid-out roads. On the east side of the city, a funerary temple and chapel were laid out. It supported a population of 2,000. One of its most enduring structures was the Deffufa, a mudbrick temple, on top of which ceremonies were performed.

Between 1500 and 1085 BC, Egypt conquered and dominated

Thirteen temples and two palaces have been excavated in Napata, which has yet to be fully excavated.

Tunisia

Carthage

Large regions of North Africa, particularly near the coasts, came under the control of Carthage at the height of its power in the third century BC.[16]: 24 The remains of Carthage are found near Tunis today and contain the remains of multiple periods ranging from the Punic period (Phoenician Carthage) to the later Arab occupation.[23] Vestiges of the Carthaginian Empire include the "Punic Ports" (the city's harbors) and a sanctuary and necropolis dedicated to Baal Hammon, known today as the Sanctuary of Tophet.[23][24][25]

After defeating Carthage, Rome progressively took over the entire coast of North Africa from Egypt to the Atlantic coast of modern-day Morocco. Major Roman sites in present-day Tunisia (the former Roman province known as Africa) include Roman Carthage, the amphitheater of El Jem, and the sites of Dougga (Thugga) and Sbeitla (Sufetula). Well-preserved sites in Libya include Sabratha and Leptis Magna. In Algeria, major sites include Timgad, Djémila, and Tipasa. In Morocco, cities such as Septa (Ceuta), Sala Colonia (Chellah), and Volubilis were founded or developed by Romans and retain remnants of their architecture.[26][27][28]

Numidia

Further west, the kingdom of Numidia was contemporary with the Phoenician civilization of Carthage and the Roman Republic. Among other things, the Numidians have left thousands of pre-Christian tombs. The oldest of these is Medracen in present-day Algeria, believed to date from the time of Masinissa (202–148 BC). Possibly influenced by Greek architecture further east, or built with the help of Greek craftsmen, the tomb consists of a large tumulus constructed in well-cut ashlar masonry and featuring sixty Doric columns and an Egyptian-style cornice.[16]: 27–29 Another famous example is the Royal Mausoleum of Mauretania in western Algeria. This structure consists of columns, a dome, and spiral pathways that lead to a single chamber.[29] A number of "tower tombs" from the Numidian period can also be found in sites from Algeria to Libya. Despite their wide geographic range, they often share a similar style: a three-story structure topped by a convex pyramid. They may have initially been inspired by Greek monuments but they constitute an original type of structure associated with Numidian culture. Examples of these are found at Siga, Soumaa d'el Khroub, Dougga, and Sabratha.[16]: 29–31

West Africa

Burkina Faso

Mouhoun Bend

At

Mauritania

Tichitt Culture

Tichitt Walata is the oldest surviving collection of settlements in

The Tichitt Tradition of eastern Mauritania dates from 2200 BCE

As areas where the Tichitt cultural tradition were present, Dhar Tichitt and Dhar Walata were occupied more frequently than Dhar Néma.

Dhar Tichitt

At

Dhar Walata/Oualata

At

Dhar Néma

In the late period of the

Dhar Tagant

At

Niger

In Niger, there are two monumental tumuli – a cairn burial (5695 BP – 5101 BP) at Adrar Bous, and a tumulus covered with gravel (6229 BP – 4933 BP) at Iwelen, in the Aïr Mountains.[49] Tenerians did not construct the two monumental tumuli at Adrar Bous and Iwelen.[49] Rather, Tenerians constructed cattle tumuli at a time before the two monumental tumuli were constructed.[49]

Nigeria

Nok Culture

Nok culture artifacts—located on the Jos Plateau in Nigeria, between the Niger River and Benue River—have been dated as far back as 790 BCE. The excavation of the Nok settlement in Samun Dikiya shows a tendency to build on hill tops and mountain peaks. However, Nok settlements have not been extensively excavated.[50]

In the central region of

Senegambia

Between 1350 BCE and 1500/1600 CE,

At

Eastern Africa

Ethiopia

In the

Aksumite

Most structures, however—such as palaces, villas, commoner's houses, and other churches and monasteries—were built of alternating layers of stone and wood. Some examples of this style had whitewashed exteriors and/or interiors, such as the medieval 12th-century monastery of

Kenya

In 2nd millennium BCE,

Central Africa

Between late 3rd millennium BCE and mid-2nd millennium CE,

Chad

Sao Civilization

Southern Africa

limpompo drystonewalling culture

Limpompo drystonewalling culture drystonewalling in the region of the limpompo existed from 200BC when the ancestors of what is the venda language speaking peoples started constructing drystonewalling to show the power of the king .

Medieval architecture

North Africa

The Islamic conquest of North Africa saw the development of

Tunisia

-

Great Mosque of Sousse (9th century)

-

Entrance of the Fatimid Great Mosque of Mahdia (10th century)

-

Kasbah Mosqueof Tunis (13th century)

-

Mosque and mausoleum of Youssef Dey in Tunis (17th century)

Algeria

The territory of present-day Algeria was ruled by various dynasties in the early Islamic period, including the

-

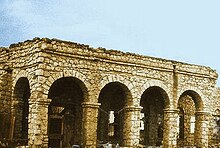

Remains of the mosque of Qal'at Bani Hammad (11th century)

-

Great Mosque of Tlemcen (11th-12th centuries, with later additions)

-

Zellij and muqarnas decoration at the entrance of the Sidi Bu Madyan Mosque in Tlemcen (14th century)

-

New Mosque in Algiers (17th century)

Morocco

Islamic architecture began in Morocco under the

-

Remains of an Idrisid mosque at Lixus

-

University of al-Qarawiyyin in Fes (founded in 9th century)

-

Almoravid Qubba in Marrakesh (early 12th century)

-

Mosque of Tinmel(12th century)

-

zillīj at Al-Attarine Madrasain Fes (14th century)

-

El Badi Palace in Marrakesh (late 16th century)

Egypt

After initially being a province of the

-

Courtyard of the Al-Azhar Mosque in Cairo, founded in 972

-

Bab al-Futuh, a Fatimid gate in Cairo (1087–92)

-

Street façade of the Aqmar Mosque (1126)

-

The Citadel of Cairo, founded in 1176

-

Exterior of the Funerary complex of Sultan Qalawun (1285), which included a mausoleum, a madrasa, and a maristan

-

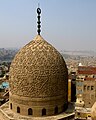

Dome of the Funerary complex of Sultan Qaytbay (1474)

-

Madrasa-Mosque of Sultan Hasan(1356–1361)

Sudan

Nubia

The Christianization of Nubia began in the 6th century. Its most representative architecture consists of churches, whose design is based on Byzantine basilicas, but which are relatively small and made of mud bricks. Vernacular architecture of the Christian period is scarce. Soba is the only city that has been excavated. Its structures are made of sun-dried bricks, the same as today, except for an arch. During the Fatimid phase of Islam, Nubia became Arabized. Its most import mosque was the Mosque of Derr.[74][75]

West Africa

At

Ghana

Ashanti

Mali

At

At the Inner Niger Delta, in the Mali Lakes Region, there are two monumental tumuli constructed in the time period of the Trans-Saharan trade for the Sahelian kingdoms of West Africa.[79] The El Oualadji monumental tumulus, which dates between 1030 CE and 1220 CE and has two human remains buried with horse remains and various items (e.g., horse harnesses, horse trappings with plaques and bells, bracelets, rings, beads, iron items), may have been, as highlighted by al-Bakri, the royal burial site of a king from the Ghana Empire.[79] The Koï Gourrey monumental tumulus, which may date prior to 1326 CE and has over twenty human remains that were buried with various items (e.g., iron accessories, an abundant amount of copper bracelets, anklets and beads, an abundant amount of broken, but whole pottery, another set of distinct, intact, glazed pottery, a wooden-beaded bone necklace, a bird figurine, a lizard figurine, a crocodile figurine), and is situated within the Mali Empire.[79]

Nigeria

Several societies in pre-colonial Nigeria built structures from earth and stone. In general, these structures were primarily defensive, repelling invaders from other tribes, but many settlements put spiritual elements into their construction. These defensive structures were primarily constructed from earth, occasionally plastered.

Dump ramparts consist of an outer ditch and inner bank and can span from 1/2 meter to 20 meters across in the largest settlements such as Benin and Sungbo's Eredo. Coursed mud walls in the Guinea and Sudan savannas were laid in layers of mud. Each layer of mud would be held in place by wooden framing, allowed to dry, and built on top of. At the most significant settlement in Koso, these walls averaged 6 meters in height, tapering from 2 meters thick at the base to 1/2 meter thick at the top. Tubali walls in northern Nigeria have two components: sun-dried mud bricks held together with mud mortar. Walls in this style have a tendency to deteriorate in wetter climates.[80]

These mud constructions were usually plastered with mud mixed with other materials. The defensive purpose of this was to create a smoother, unscalable surface to help repel attackers. However, some plaster has been found with blood, bone remains, gold dust, oil, and straw mixed in. Some of these materials were functional, adding strength, while others had spiritual meanings, possibly to defend against evil spirits.[80]

Benin City in particular had sophisticated house and urban planning. Houses had several rooms and were usually roofed, enclosing private quarters, sacred spaces, and rooms for receiving guests. Usually, multiple houses would enclose a shared courtyard. When it rained, the house roofs would collect water into a space in the courtyard for later use. Houses would have public frontage along long, straight roads. The city had markets and the chief's palace in the center of the city, with dominant and subordinate roads leading outwards. HM Stanely, quoted in Asomani-Boateng, Raymond (2011-11), described the roads as "...fenced with tall [water cane] neatly set very close together in uniform rows..." possibly for privacy.[81]

More sophisticated construction methods include stone and brick constructions, with and without mortar, plaster, and accompanying defensive structures. Fired brick constructions were observed in settlements in northeast Nigeria, such as historic Kanuri buildings. Many of the bricks have since been removed for new constructions. Laterite block walls with clay mortar were found in northwest Nigeria, possibly inspired by Songhai constructions. Walls built from stone without mortar have been found where societies could obtain sufficient stone, most notably in Sukur. None of these constructions have been observed with additional plastering.[80]

The Sukur World Heritage Site is especially significant, with extensive terraces, walls, and infrastructure. Walls separate homes, animal pens, and granaries, while terraces often include spiritual items such as sacred trees or ceramic shrines. Early iron foundries were also present, usually placed close to the homes of their owners.[82]

Broadly, three styles of residential architecture can be identified in indigenous Nigerian architecture, relating to the people groups which developed them.

- Hausa architecture uses plastered adobe to create monolithic walls. Roofing is provided by shallow domes and vaults made from structural timber beams covered by laterite and earth. Homesteads are bounded by perimeter walls with both circular and linear interior divisions with one clearly defined entrance.

- Yoruba architecture uses cured earth walls to support roof timbers, over which leaf or woven grass roofing is applied. These walls are usually homogeneous mud structures, though wattle-and-daub techniques can be found in certain locations. Space is divided into individual units which are then connected by proximity and walls into a compound with courtyards and private spaces. Multiple entrances and exits allow access to accessory facilities such as kitchens.

- Igbo architecture uses similar construction techniques and materials as Yoruba architecture, but varies significantly in spatial arrangement. No unified compound walls exist in these constructions. Instead, individual units are related to a central leader's hut, with significance attached to relative position and size.

These elements are believed to affect present-day residential house design, especially when designating spaces as public, semi-public, semi-private, or private.[83]

Benin

The rise of kingdoms in the West African coastal region produced architecture which drew on indigenous traditions, utilizing wood.

They extend for some 16,000 kilometres in all, in a mosaic of more than 500 interconnected settlement boundaries. They cover 6500 square kilometres and were all dug by the Edo people. In all, they are four times longer than the Great Wall of China, and consumed a hundred times more material than the Great Pyramid of Cheops. They took an estimated 150 million hours of digging to construct, and are perhaps the largest single archaeological phenomenon on the planet.[85]

In 1691, the Portuguese Lourenco Pinto observed: "Great Benin, where the king resides, is larger than Lisbon; all the streets run straight and as far as the eye can see. The houses are large, especially that of the king, which is richly decorated and has fine columns. The city is wealthy and industrious. It is so well governed that theft is unknown and the people live in such security that they have no doors to their houses."[86]

Benin City's planning and design was done according to careful rules of symmetry, proportionality and repetition now known as fractal design.[87] The main streets had underground drainage made of a sunken impluvium with an outlet to carry away storm water. Many narrower side and intersecting streets extended off them.[88]

Hausa Kingdoms

The important Hausa Kingdoms city state of Kano was surrounded by a wall of reinforced ramparts of stone and bricks. Kano contained a citadel near which the royal court resided. Individual residences were separated by earthen walls. The higher the status of the resident the more elaborate the wall. The entrance-way was maze-like to keep women secluded. Inside, near the entrance, were the abodes of unmarried women. Further on were slave quarters.[89]

Gobarau Mosque

Gobarau Mosque is believed to have been completed during the reign of

Yoruba

The

Eastern Africa

Burundi

Burundi never had a fixed capital. The closest thing to it was a royal hill. When the king moved, his new location became the insago. The compound itself was enclosed inside a high fence and had two entrances. One was for herders and herds. The other was to the royal palace, which was itself surrounded by a fence. The royal palace had three royal courtyards, each serving a particular function: one for herders, one as a sanctuary, and one encompassed by kitchen and granary.[92]

Ethiopia

Throughout the medieval period, the monolithic influences of Aksumite architecture persisted, with its influence felt strongest in the early medieval (Late Aksumite) and Zagwe periods (when the churches of Lalibela were carved). Throughout the medieval period, and especially during the 10th to 12th centuries, churches were hewn out of rock throughout

The most famous examples of Ethiopian rock-hewn architecture are the 11 monolithic churches of Lalibela, carved out of the red volcanic tuff found around the town. Although later medieval hagiographies attribute all 11 structures to the eponymous king

Kenya

Rwanda

Nyanza was the royal capital of Rwanda. The king's residence, the Ibwami, was built on a hill. Surrounding hills were occupied by permanent or temporary dwellings. These dwellings were round huts surrounded by big yards and tall hedges to separate the compounds. The Rugo, the royal compound, was encircled by reed fences encompassing thatched houses. The houses for the king's entourage were carpeted with mats and had clay hearths in the center. For the king and his wife, the royal house was close to 200-100 yards in length and looked like a huge maze of connected huts and granaries. It had one entrance that lead to a large public square called the karubanda.[95]

Somalia

Somali architecture has a rich and diverse tradition of designing and engineering different types of construction, such as masonry, castles, citadels, fortresses, mosques, temples,

In ancient Somalia, pyramidical structures known in Somali as taalo were a popular burial style, with hundreds of these dry stone monuments scattered around the country today. Houses were built of dressed stone similar to the ones in Ancient Egypt,[96] and there are examples of courtyards, and large stone walls, such as the Wargaade Wall, enclosing settlements.

The peaceful introduction of Islam in the early medieval era of Somalia's history brought Islamic architectural influences from

Dhulbahante garesa

In the official Dervish-written letter's description of the 1920 air, sea and land campaign and the fall of Taleh in February 1920, in an April 1920 letter transcribed from the original Arabic script into Italian by the incumbent Governatori della Somalia, the British are described taking twenty-seven garesas or 27 houses from the Dhulbahante clan:[98][a]

Ai primi di aprile giungeva, a mezzo di corrieri dervisc di Belet Uen, una lettera diretta dal Mulla "Agli Italiani" con la quale, in sostanza, giustificando la sua rapida sconfitta coll'attriburla a defezione dei suoi seguaci Dulbohanta, chiedeva la nostra mediazione presso gli Inglesi ... Gl'Inglesi che sapevano questo ci son piombati addosso con tutta la gente e con sei volatili (aeroplani) ... i Dulbohanta nella maggior parte si sono arresi agli inglesi e han loro consegnato ventisette garese (case) ricolme di fucili, munizioni e danaro. |

In early April there came, by way of dervish couriers of Beledweyne, a letter sent by the Mullah "To The Italians" in which, in substance, he justified his rapid defeat by attributing it to the defection of his Dhulbahante followers and asked for our mediation with the English. The English, who knew this, descended on us with all their men and with six birds (airplanes)." ... the Dhulbahante surrendered for the most part to the British and handed twenty-seven garesas (houses) full of guns, ammunition and money over to them. |

Tanzania

Engaruka is a ruined settlement on the slopes of Mount Ngorongoro in northern Tanzania. Seven stone-terraced villages comprised the settlement. A complex structure of stone channels along the mountain's base was used to dike, dam, and level surrounding river waters for irrigation of individual plots of land. Some of these irrigation channels were several kilometers long. The channels irrigated a total area of 5,000 acres (20 km2).[99][100]

Swahili States

Farther south, increased trade with Arab merchants, and the development of ports, saw the birth of

A visitor in 1331 AD considered the Tanzanian city Kilwa to be of world class. He wrote that it was the "principal city on the coast the greater part of whose inhabitants are Zanj of very black complexion." Later on he says that: "Kilwa is one of the most beautiful and well-constructed cities in the world. The whole of it is elegantly built."

Uganda

Buganda

Initially, the hilltop capital, or kibuga, of Buganda would be moved to a new hill with each new ruler, or Kabaka. In the late 19th century, a permanent kibuga of Buganda was established at Mengo Hill. The capital, 1.5 miles across, was divided into quarters corresponding to provinces, with each chief building dwellings for his wife, slaves, dependents and visitors. Large plots of land were available for planting bananas and fruits. Roads were wide and well maintained.[102]

Kitara and Bunyoro

In western Uganda, there are numerous earthworks near the Katonga River. These earthworks have been attributed to the Empire of Kitara. The most famous, Bigo bya Mugenyi, is about 4 square miles (10 km2). The ditch was dug by cutting through 200,000 cubic metres (7,100,000 cu ft) of solid bedrock and earth. The earthwork rampart was about 12 feet (3.7 m) high. It is not certain whether its function was for defense or pastoral use. Little is known about the Ugandan earthworks.[103]

Central Africa

Chad

Kanem-Bornu

Democratic Republic of the Congo

Kongo

With a population of more than 30,000,

Kuba

The capital of the Kuba Kingdom was surrounded by a 40-inch-high (1.0 m) fence. Inside the fence were roads, a walled royal palace, and urban buildings. The palace was rectangular and in the center of the city.[106]

Luba

The

Lunda

Musumba the capital of the Kingdom of Lunda, was 100 kilometres (62 mi) from the Kasai River, in open woodland, between two rivers 15 kilometres (9.3 mi) apart. The city was surrounded by fortified earthen ramparts and dry moats. The compound of the Mwato Yamvo (sovereign ruler) was surrounded by large fortifications of double-layered tree, or wood, ramparts. Musumba had multiple courtyards with designated functions, straight roads, and public squares. Its cleanliness was noted by European observers.[107]

Mozambique

Maravi

The Maravi people built bridges (uraro) of bamboo because of changing river depths. Bamboo was placed parallel to each other and tied together by bark (maruze). One end of the bridge would be tied to a tree. The bridge would curve downward.

Zambia

Eastern Lunda

The Eastern Lunda dwelling of the Kazembe was described as containing fenced roads a mile long. The enclosing walls were made of grass, 12 to 13 span in height. The enclosed roads led to a rectangular hut opened on the west side. In the center was a wooden base with a statue on top of about 3 span in height.[108]

Southern Africa

Madagascar

The Southeast Asian origins of the first settlers of Madagascar are reflected in the island's architecture, typified by rectangular dwellings topped with peaked roofs and often built on short stilts. Coastal dwellings, generally made of plant materials, are more like those of East Africa; those of the central highlands tend to be constructed in cob or brick. The introduction of brick-making, by European missionaries in the 19th century, led to the emergence of a distinctly Malagasy architectural style that blends the norms of traditional wooden aristocratic homes with European details.[109]

In the mid-2nd millennium CE, the

Namibia

The fortress of

South Africa

Sotho-Tswana

At sites such as Kweneng' Ruins, the Tswana lived in city states with stone walls and complex sociopolitical structures that they built in the 1300s or earlier. These cities had populations of up to 20,000 people, which at the time rivalled Cape Town in size.[113][114][115]

Zulu and Nguni

Zulu Architecture was constructed with more perishable materials. Dome-shaped huts typically come to mind when one thinks of Zulu dwellings, but later on their design evolved into dome over cylinder-shaped walls. Zulu capital cities were elliptical in plan. The exterior was lined with a durable wood palisade. Domed huts, in rows of 6 to 8, stood just inside the palisade. In the center was the kraal, used by the king to examine his soldiers, hold cattle, or conduct ceremonies. It was an empty circular area at the center of the capital, enclosed by a less durable interior palisade, compared to the exterior. The entrance to the city was opposite to the fortified royal enclosure called the Isigodlo.

Zimbabwe

Mapungubwe

Great Zimbabwe

Great Zimbabwe was the largest medieval city in sub-Saharan Africa.[citation needed] It was constructed and expanded for more than 300 years in a local style that eschewed rectilinearity for flowing curves. Neither the first nor the last of some 300 similar complexes located on the Zimbabwean plateau, Great Zimbabwe is set apart by the large scale of its structures. Its most formidable edifice, commonly referred to as the Great Enclosure, has dressed stone walls as high as 36 feet (11 m) extending for approximately 820 feet (250 m),[116] making it the largest ancient structure south of the Sahara. Houses within the enclosure were circular and constructed of wattle and daub, with conical thatched roofs.

Torwa State

Khami was the capital of the Kingdom of Butua during the Torwa dynasty. It was the successor to Great Zimbabwe and where the techniques of Great Zimbabwe were further refined and developed. Elaborate walls were constructed by connecting carefully cut stones to form terraced hills.[117]

Modern architecture

African rural architecture

Rural African architecture research has generally been viewed in a limited perspective and has widely been considered primitive in building technology and techniques.[118] Architecture as a practice in rural Africa also extends to the construction of religious dwellings as well.[119]

Typically, materials such as wood, metal, terra-cotta, and stone were used in the construction of armature, walls, floors, and roofing for rural homes and community buildings. Changes in structure and material are based on changes in the climate, what building materials are available, and the techniques and skills of an area. As the construction of these buildings required many individual procedures, the overall execution of constructing homes and communal dwellings within a rural village is a communal process. However, the owner [of the dwelling] has the most control over the construction process and is considered the master builder.[120]

Sub-Saharan African rural architecture

Although there generally a wide range of architectural styles across Africa, sub-saharan Africa encompasses the widest diversity in architectural styles due to the extensive scope of physical [climate] settings.[121]

Coastal rainforest

In the coastal rainforest belt of Africa, where temperatures are regularly torrid and humid regardless of daytime or nighttime, rural dwellings require interior cross-ventilation to ensure maximum bodily comfort. To achieve this, the craftsperson would incorporate openings into the dwelling. Open, screen-like walls and elevated floorings would be built to provide natural airflow throughout the building.[122]

Inland savannah

In contrast to the coastal rainforest belt, the inland savannah climate, which is composed of an annual, brief rainy season and a long, dry season in which chilling winds blow into the region from the Sahara, require an architectural solution that can both cut the biting cold of dusk and prevent individuals from enduring the overwhelming heat of the midday sun.[123]

Modern African Rural Architecture [Ethiopia, Ghana, Nigeria, and South Africa]

Ethiopia

Structures neighboring the city of Lalibela, Ethiopia like the Monolithic churches have been hewed from stones within the ground.[124][125] Systems of catacombs were built inside for ceremonial purposes as were ditches imitating the River Jordan in Jerusalem and the ditches separate the churches into three groups, five in the north, five in the east and two in west. These churches were carved out in the 12th century during King Lalibela's reign. Another church that can illustrate the architecture style and design in Ethiopia in the modern era is the Holy Trinity Cathedral in Addis Ababa which contains the tombs of Emperor Haile Salassie, his wife, and those who were executed during the Italian regime's occupation.[126] It is at the epicenter of the capital and in close proximity to the imperial palace. Materials used in this structure includes a huge quantity of copper for the dome and statues positioned in various locations on and around the cathedral. It should also be noted that it imitates the Aksumites (Kingdom of Axum) artistic design.

Ghana

In Ghana, Larabanga Mosque is a prime example in building from packed earth which was and continues to be a method used today.[127] Sudanese architecture influences this mosque but it is notably smaller than many mosques that exist in West Africa. As construction of the mosque depends on the natural materials available, there is an environmental strain in Ghana and surrounding countries that use this method of building housing. The mosque is held together by the logs protruding from the building surface. The exterior of the mosque has whitewashed walls which are renewed every year.

Nigeria

The Demas Nwoko is a chapel constructed between 1967 and 1975 using locally sourced materials such as concrete stone, brick, stained glass and wood.[128] The interior walls of the chapel are covered with crosses of all sizes and it appears as if they are stained glass as they are luminescent. Unlike chapels, housing compounds in Nigeria frequently had a communal area like courtyards or shared spaces which were an important social aspect for residents. Emir's Palace also known as The Hausa Architecture in Zaria is traditionally divided into three parts: a private area (women's area), semi private area, and public area.[129] The palace is surrounded by the city. Nigerian architecture was shaped by Islamic culture where the women were sheltered and protected by private spaces the compound provided. Like Emir's palace, the Yoruba structure has large family residential areas in them and courtyards were commonly used by everyone.[130]

South Africa

In 1948 architecture in South Africa was heavily influenced by the Apartheid as segregation was enforced in all aspects of life.[131] The Windhoek Airport, today known as Eros, was built in 1957, and the post office in Polokwane, South Africa, was constructed in the capital of Limpopo Province and had similar groundwork to the airport. The floor plan for the airport terminal had European and non-European entrances and exits. The post office is U-shaped and like the airport there are separate entrances and exits. Brazilian modernism affected how architecture changed in the mid-twentieth century in South Africa.

Modern Islamic African Architecture

In other areas of the world Islamic architecture consists of palaces, tombs, and mosques. In West Africa, the mosque itself embodies Islam.[132] The layout of a mosque is predetermined by Islamic orthodoxy coming from the idea that rejecting certain elements, like a minaret, is seen as offensive to the religion itself. The main focus of material can be seen in mud architecture. From this architectural method came several variations, the most recent being the Bobo Dioulasso and the Mosquée de Kong [Mosque of Kong].[133] These types have a focus on expression of a politico-religious structure within a village, different from the earlier mosques focused on imperial organization and which were much bigger in size.[133] These two types of mosques are smaller. The difference between the Bobo and Kongo type lies in having to adapt to climate conditions as opposed to cultural tradition. While the basics of mosques remains the same throughout the region, there are variations within Africa mostly dependent on the climate of the area and the accommodations that need to be made for that specific region.

Grand Mosque of Bobo-Dioulasso

At Bobo-Dioulasso, vertical buttresses minarets are a part of the mosques, flaring out and thickening of the buttresses at the base of these elements are still evident but disappearing due to reduced scale and changes in the climate.[133] Projecting timbers and horizontal bracing are added due to the increased humidity of the southern savannah. There are parts of the classic mosque within the modern mosque that still remain. This can be seen in the enclosed prayer hall and interior courtyard.

Mosquée de Kong [Mosque of Kong]

Heavier buttressing is required in the Mosque of Kong because of more rain in the area. This area also sits closer to a rainforest, making wood a material that can be more easily accessed for reinforcement within the structure. Due to the generally wet climate, this mosque also requires more maintenance due to consistent erosion.

Kawara Mosque

One last example can be seen within the Kawara mosque. The Kawara lacks verticality or monumentality, but is clear in its three dimensions.[134]

Ethiopia

External influences

In the early modern period, Ethiopia's absorption of diverse new influences—such as Baroque, Arab, Turkish and Gujarati Indian styles—began with the arrival of Portuguese

Some Turkish influence may have entered the country during the late 16th century during Ethiopia's war with the Ottoman Empire (see

Emperor

Europeans and European influences

Afrikaner

Cape Dutch architecture is traditional

Colonial fortifications in West Africa

Early European colonies on the West African coast built large forts, as can be seen at

Eclecticism

European artists in the 18th century would go out to Africa and the Middle East in hopes of finding new inspiration to include in their art. These travels became common and changed political and cultural relations between Africa, the Middle East, and Europe.

Modernism

The effect of modern architecture began to be felt in the 1920s and 1930s. Le Corbusier designed several never-built schemes for Algeria, including ones for Nemours and for the reconstruction of Algiers. Elsewhere, Steffen Ahrends was active in South Africa, and Ernst May in Nairobi and Mombasa.

Eritrea

Italian futurist architecture heavily influenced the designs of Asmara. Planned villages were constructed in Libya and Italian East Africa, including the new town of Tripoli, all utilising modern designs.

After 1945,

Morocco

1953 CIAM

At the 1953 Congrès Internationaux d'Architecture Moderne (CIAM), Écochard presented, along with Georges Candilis, the work of ATBAT-Afrique—the Africa branch of Atelier des Bâtisseurs, founded in 1947 by figures including Le Corbusier, Vladimir Bodiansky, and André Wogenscky. It was a study of Casablanca's bidonvilles entitled "Habitat for the Greatest Number".[141][142] It argued against doctrine, arguing that architects must consider local culture and climate in their designs.[143][137][144] This generated great debate among modernist architects around the world and eventually provoked a schism.[143][145][146]

Post-independence

The French-Moroccan architect Jean-François Zevaco built experimental modernist works in Morocco.[147] Abdeslam Faraoui, Patrice de Mazières, and Mourad Ben Embarek were also notable modernist architects in Morocco.[148]

Post-colonial architecture

A number of new cities were built following the end of

Experimental designs have also appeared, most notably the

Other notable structures of recent years have been some of the world's largest dams. The

Traditional revival

The revival of interest in traditional styles can be traced to Cairo in the early 19th century. This had spread to Algiers and Morocco by the early 20th century, from which time colonial buildings across the continent began to consist of recreations of traditional African architecture, the Jamia Mosque in Nairobi being a typical example. In some cases, architects attempted to mix local and European styles, such as at Bagamoyo.

See also

Notes

- ^ *To see the discussion for the Italian-language wiki community on the Caroselli garesa quote, see this link and this link

*The Caroselli source ascribes "garesa" to British captured forts; for a quote that Taleh fort was British captured, see quote "It was most fortunate that Tale was so easily captured" (Douglas Jardine, 1923).

References

- ISBN 978-0-8135-2613-3.

- S2CID 161078189.

- ^ Osypiński, Piotr (2020). "Unearthing Pan-African crossroad? Significance of the middle Nile valley in prehistory" (PDF). National Science Centre.

- OCLC 1374884636.

- OCLC 1374884636.

- ^ S2CID 126951785.

- ^ S2CID 249349324.

- ^ OCLC 826685273.

- ^ S2CID 162877973.

- ^ S2CID 4057938.

- S2CID 133240608.

- ^ S2CID 144968825.

- ^ S2CID 126608903.

- S2CID 144518526.

- ^ S2CID 236340668.

- ^ ISBN 9780631207672.

- ^ "ancient Egyptian architecture | Types, History, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2021-07-22.

- ISBN 978-0-313-32501-4.

- ^ Bietak, Manfred. The C-Group culture and the Pan Grave culture Archived May 11, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. Cairo: Austrian Archaeological Institute

- ^ Kendall, Timothy. The 25th Dynasty Archived April 30, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. Nubia Museum Archived June 15, 2009, at the Wayback Machine: Aswan

- ^ Kendall, Timothy. The Meroitic State: Nubia as a Hellenistic African State. 300 B.C.-350 AD Archived April 26, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. Nubia Museum Archived June 15, 2009, at the Wayback Machine:Aswan

- ^ Prof. James Giblin, Department of History, The University of Iowa. Issues in African History Archived April 15, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Archaeological Site of Carthage". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 2022-01-11.

- ^ "Punic Ports | Tunis, Tunisia Attractions". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 2022-01-11.

- ^ "Sanctuary of Tophet | Tunis, Tunisia Attractions". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 2022-01-11.

- ^ Ennabli, Abdelmajid (2000). "North Africa's Roman art. Its future". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 2014-09-12. Retrieved 2022-01-11.

- ISBN 9789012001052.

- ^ "Frontiers of the Roman empire | African World Heritage Sites". www.africanworldheritagesites.org. Retrieved 2022-01-11.

- ISBN 978-0-684-82667-7.

- ^ S2CID 255557451.

- S2CID 161981607.

- .

- ISBN 978-0-521-21592-3.

- ISBN 978-1-55876-303-6.

- S2CID 159184437.

- ^ S2CID 128545688.

- ^ S2CID 130234059.

- ^ S2CID 134223231.

- ^ S2CID 149031750.

- ^ S2CID 161938622.

- ^ S2CID 248132575.

- ^ S2CID 111618144.

- S2CID 194063851.

- ^ S2CID 147397386.

- ^ S2CID 160853354.

- ^ S2CID 190294373.

- S2CID 236798102.

- S2CID 243375056.

- ^ S2CID 202916401.

- ISBN 978-1-55876-303-6.

- ^ S2CID 162190915.

- ^ Holl, Augustin F. C. (May 2018). "Megaliths and Cultural Landscape: Archaeology of the Petit Bao Bolon Drainage". Preserving African Cultural Heritage. Panafrican Archaeological Association. p. 120.

- S2CID 222116314.

- ^ S2CID 161053129.

- ^ "Qantara - Great Mosque of Kairouan". www.qantara-med.org. Retrieved 2021-07-22.

- ^ "Mosque of Aḥmad ibn Ṭūlūn | building, Cairo, Egypt". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2021-07-22.

- ^ a b c Marçais, Georges (1954). L'architecture musulmane d'Occident. Paris: Arts et métiers graphiques.

- ^ ISBN 9780300218701.

- ISBN 0-415-02063-8. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ ISBN 9780195309911.

- ^ OCLC 856037134.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-062455-2.

- ISBN 9780195309911.

- ^ Stewart, Courtney Ann. "Art and Architecture of Morocco and Muslim Spain: Bronze Age to Idrisid Dynasty". Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ISSN 1543-950X.

- ISBN 9780748646821.

- ISBN 9780300218701.

- ISBN 978-0-300-21870-1.

- ^ Soo-Hoo, Anna. ""A Very Sweet Present: Moroccan Sugar Loaves" by Iziar de Miguel". Retrieved 2020-05-30.

- ISBN 9780195309911.

- ^ a b Williams, Caroline (2018). Islamic Monuments in Cairo: The Practical Guide (7th ed.). Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press.

- ^ Raymond, André. 1993. Le Caire. Fayard.

- ISBN 9789774160776.

- ^ Grossmann, Peter. Christian Nubia and Its Churches Archived May 16, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. Cairo: German Archaeological Institute

- ^ Shinnie, P.L. Medieval Nubia Archived 2018-01-03 at the Wayback Machine. Khartoum:Sudan Antiquities Service,1954

- ^ Historical Society of Ghana. Transactions of the Historical Society of Ghana, The Society, 1957, pp81

- ^ Davidson, Basil. The Lost Cities of Africa. Boston: Little Brown, 1959, pp86

- ^ "Ashante Shrine". Zamani Project. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- ^ OCLC 174131337.

- ^ )

- S2CID 144469644.

- ^ "Sukur Cultural Landscape". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 2019-11-13.

- ^ Osasona, Cordelia O., From traditional residential architecture to the vernacular: the Nigerian experience (PDF), Ile-Ife, Nigeria: Obafemi Awolowo University, retrieved 3 December 2019

- ISBN 9780865436107.

- ^ Pearce, Fred. African Queen. New Scientist, 11 September 1999, Issue 2203.

- ISBN 9783030882822.

- ISBN 978-177711791-7. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- ISBN 978-100037333-2. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- ISBN 978-1-55876-303-6.

- ^ "Gobarau Minaret Katsina State :: Nigeria Information & Guide". www.nigeriagalleria.com. Retrieved 2022-06-09.

- ^ "Gobarau, Katsina, phone +234 903 249 8940". ng.africabz.com. Retrieved 2022-06-09.

- ISBN 978-1-55876-303-6.

- ^ "Thimlich Ohinga Archaeological Site". 2018.

- ^ Secrets in stone. Who built the stone settlements of Nyanza Province. Kenya Past and Present. 2006.

- ISBN 978-1-55876-303-6.

- ^ Man, God and Civilization pg 216

- ^ Diriye, p.102

- ^ Ferro e Fuoco in Somalia, da Francesco Saverio Caroselli, Rome, 1931; p. 272. "i Dulbohanta nella maggior parte si sono arresi agli inglesi e han loro consegnato ventisette garese (case) ricolme di fucili, munizioni e danaro." (English: "the Dhulbahante surrendered for the most part to the British and handed twenty-seven garesas (houses) full of guns, ammunition and money over to them."viewable link

- ISBN 978-0-393-05581-8.

- ISBN 978-1-57958-453-5.

- ^ African Archaeological Review, Volume 15, Number 3, September 1998, pp. 199-218(20)

- ISBN 978-1-55876-303-6.

- ISBN 978-0-521-65221-6.

- ISBN 978-1-55876-303-6.

- ISBN 978-1-55876-303-6.

- ISBN 978-1-55876-303-6.

- ISBN 978-0-521-28444-8.

- ISBN 978-0-86543-124-9.

- ^ Acquier, Jean-Louis. Architectures de Madagascar. Paris: Berger-Levrault.

- ISBN 978-0-521-65221-6.

- ISBN 978-0-333-59957-0.

- ISBN 978-0-521-68297-8.

- ^ "Lost City in South Africa Discovered Hiding Beneath Thick Vegetation". Live Science. 6 February 2019.

- ^ "Nyame Akuma". 2006.

- ISBN 9781776142309.

- ISBN 978-1-56367-462-4.

- ISBN 978-0-333-59957-0.

- JSTOR 43643992– via JSTOR.

- JSTOR 988854– via JSTOR.

- JSTOR 988854– via JSTOR.

- JSTOR 988854– via JSTOR.

- JSTOR 988854– via JSTOR.

- JSTOR 988854– via JSTOR.

- S2CID 129444518.

- ^ Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "UNESCO World Heritage Centre - Document - Report of the UNESCO/ICOMOS/ICCROM Advisory mission to Rock-Hewn Churches, Lalibela (Ethiopia), 20-25 May 2018". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 2023-02-21.

- S2CID 253853684.

- JSTOR 3334324.

- JSTOR 3335257.

- S2CID 202901961.

- JSTOR 991791.

- S2CID 144887604.

- JSTOR 3334324.

- ^ JSTOR 3334324.

- JSTOR 3334324.

- ^ Jona Schellekens, "Dutch Origins of South-African Colonial Architecture," Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 56 (1997), pp. 204–206.

- S2CID 165308576.

- ^ ISBN 978-9920-9339-0-2.

- ^ إيلي أزاجوري.. استعادة عميد المعماريين المغاربة [Elie Azagoury .. Acknowledging the Dean of Moroccan Architects]. Al-Araby (in Arabic). 19 December 2019. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- ^ "Adaptations of Vernacular Modernism in Casablanca". Retrieved 2020-04-15.

- ^ "Casablanca 1952: Architecture For the Anti-Colonial Struggle or the Counter-Revolution". THE FUNAMBULIST MAGAZINE. 2018-08-09. Retrieved 2020-04-17.

- ^ "TEAM 10". www.team10online.org. Retrieved 2020-04-17.

- S2CID 210539858.

- ^ a b "The Gamma Grid | Model House". transculturalmodernism.org. Retrieved 2019-10-18.

- ^ "TEAM 10". www.team10online.org. Retrieved 2020-04-17.

- ^ Pedret, Annie. "TEAM 10 Introduction". www.team10online.org. Retrieved 2019-10-18.

- ISBN 9781136895487.

- ISSN 1969-248X.

- ISBN 978-9920-9339-0-2.