Aguardiente

This article should specify the language of its non-English content, using {{lang}}, {{transliteration}} for transliterated languages, and {{IPA}} for phonetic transcriptions, with an appropriate ISO 639 code. Wikipedia's multilingual support templates may also be used. (June 2020) |

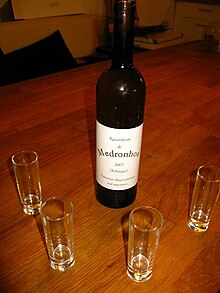

Various bottles of aguardiente | |

| Country of origin | Spain, Portugal |

|---|---|

| Alcohol by volume | 29% to 60% |

Aguardente (

Etymology

The word is a compound of the Iberian languages' words for "water" (agua in Castilian; aigua in Catalan; água in Portuguese; auga in Galician) and "burning"/"fiery" (ardiente in Castilian; ardent in Catalan; ardente in Portuguese and Galician). A comparable word in English is "firewater",[1] though the English term is colloquial or humorous, whereas aguardiente is stylistically neutral in Spanish.

Definition

Aguardientes are strong alcoholic beverages obtained by

Cane aguardiente and cachaça are similar but distinct products. Brazil thereafter defined cane aguardiente as an alcoholic beverage of between 38% and 54% ABV, obtained by simple fermentation and distillation of sugarcane that has already been used in sugar production and has a distinct flavor similar to rum. Cachaça, on the other hand, is an alcoholic beverage of between 38% and 48% ABV, obtained by fermenting and distilling sugarcane juice, and may have added sugar up to 6 g/L.

Regulation

According to Spanish and Portuguese versions of European Union spirits regulations,[2] aguardiente and aguardente are generic Spanish and Portuguese terms, respectively, for some of the distilled spirits that are fermented and distilled exclusively from their specified raw materials, contain no added alcohol or flavoring substances, and if sweetened, only "to round off the final taste of the product". However, aguardiente and aguardente are not legal denominations.[3]

Instead, different categories of aguardientes (spirits in the English version) are established according to raw materials. In the Spanish version, wine spirit (

Regional variations

Some drinks named aguardiente or similar are of different origins (grape pomace, sugarcane); other drinks with the same origin may have different names (clairin, brandy).

Brazil

One form that can be qualified as moonshine is known as "Maria Louca" ("Crazy Mary"). This is aguardiente, made in jails by inmates. It can be made from many cereals, ranging from beans to rice, or whatever can be converted into alcohol, be it fruit peels or candy, using improvised and illegal equipment.

Cape Verde

Grogue, also known as grogu or grogo (derived from English grog), is a Cape Verdean alcoholic beverage, an aguardiente made from sugarcane processed in a trapiche. Its production is fundamentally artisanal, and nearly all the sugarcane is used in producing grogue.

Chile

In

Colombia

In Colombia, aguardiente is an anise-flavored liqueur derived from sugarcane, popular in the Andean region. Different flavors are obtained by adding different amounts of aniseed, leading to extensive marketing and fierce competition between brands. Aguardiente has 24%–29% alcohol content. Other anise-flavored liqueurs similar to aguardiente, but with a lower alcohol content, are also sold. Since the Spanish era, aguardiente has maintained the status of the most popular alcoholic beverage in the Andean regions of Colombia, with the notable exception of the Caribbean region, where rum is most popular. Generally, aguardiente is rarely drunk in cocktails and usually drunk neat.

On the Caribbean coast, there is a moonshine called "Cococho", an aguardiente infamous for the number of blindness cases due to the addition of methanol.

Costa Rica

In Costa Rica, it is 30% alcohol, with a neutral flavor. The Costa Rican government tightly controls Guaro to help prevent clandestine production.

Guam and the Mariana Islands

In

Ecuador

In

Mexico

In Mexico, aguardiente goes by many names, including habanero.[9] In the state of Michoacán, charanda is a traditional rum-like sugar cane aguardiente.

Casa Berreteaga marketed an aguardiente called "Berreteaga", which used sugarcane sourced from the Coxcatlan region of Puebla. Berreteaga was a fortified wine made from rum and sweet wine (usually Muscat) or (uncommonly) a sweet brandy that was then aged in oak barrels.

Portugal

Portuguese aguardente has several varieties. Aguardente vínica is distilled from either good quality or undrinkable wine. It is mostly used to fortify wines such as port or aged to make aguardente velha (old burning water), a kind of brandy. Aguardente bagaceira is made from pomace to prevent waste after the close of wine season. It is usually bootlegged, as most drinkers only appreciate it in its traditional formulation of 50% to 80% ABV. A common way to drink it is as café com cheirinho ("coffee with a little scent"), a liqueur coffee made with espresso.[10]

In the Azores, this espresso-aguardente combination is commonly referred to as café com música ("coffee with music"). Aguardente Medronho is a variety distilled from the fruit of the Arbutus unedo tree.[citation needed]

In Madeira, it is the core ingredient for poncha, a beverage around which a festival is based. Most of the aguardente from the region is made from sugarcane.[citation needed]

Spain

In certain areas of the Pyrenees in Catalonia, aiguardent, as it is known in Catalan, is used as an essential ingredient in the preparation of tupí, a type of cheese.[11]

Galicia is renowned for the quality and variety of its aguardientes, including augardente de bagazo (aguardiente de Orujo), which is obtained from the distillation of the pomace of grapes, and is clear and colorless. It typically contains over 50% alcohol, sometimes significantly more, and is still made traditionally in many villages across Galicia today. Augardente de herbas, usually yellow, is a sweet liqueur made with augardente de bagazo and herbs (herbas), with chamomile being a substantial ingredient.[12] Licor café (typical distilled drink in the province of Ourense), black in color, is a sweet liqueur made with augardente de bagazo, coffee (café), and sugar. Crema de augardente or crema de caña is a cream liqueur based on augardente, coffee, cream, milk, and other ingredients. It is similar to Irish cream liqueur. In some places in Galicia, a small glass is traditionally taken at breakfast as a tonic before a hard day's work on the land. The word "orujo" is Spanish and not Galician, but is used to distinguish Galician and some Spanish augardentes from those of other countries.[13]

Most of the moonshine in Spain is made as a byproduct of winemaking by distilling the squeezed skins of the grapes. The essential product is called "orujo" or "aguardiente" (burning water). The homemade versions are usually more potent and have a higher alcoholic content, well over the 40% that the commercial versions typically have. It is often mixed with herbs, spices, fruits, or other distillates. Types include

United States

During the

See also

References

- ^ Odell, Kat (July 2019). "Why Colombia's National Drink Could Be Your New Summer Go-To". Vogue. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- ^ "Regulation (EC) No 110/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 January 2008". EUR-Lex.. See the Spanish version here and the Portuguese version here.

- ^ Chapter I, Article 5. – General rules concerning the categories of spirit drinks.

- ^ Annex II, 1–14.

- ^ Annex III.

- ^ "Tuba: Guam's 'Water of Life' lives on". Stars and Stripes Guam. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- ^ "Filipinos on Guam: Cultural contributions". Guampedia. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- ^ "Tuba taxed, outlawed, now threatened by rhino beetle". Pacific Daily News. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- ISBN 9781566917117. Archived from the originalon 13 April 2017. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

- ^ "Lisboando – Guia de Lisboa". Retrieved 2012-08-17.

- ^ "Formatge de tupí". gastroteca.cat (in Catalan). Prodeca. 2019. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

Aquest producte és el resultat del reaprofitament d'altres formatges. En resulta un dels formatges tradicionals més representatius de les comarques pirinenques, fruit de l'experiència dels pastors que reaprofitaven els formatges vells i secs.

- ^ Galicia Espallada.

- ^ Gastronomia Galega Archived November 15, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- ISBN 978-0-520-21351-7. Retrieved 24 November 2011.