Akritas plan

The Akritas plan (

Background

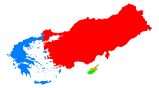

Cyprus, an island lying in the eastern Mediterranean sea was ruled by several conquerors during its history. In the late 19th century, the Ottoman Empire handed Cyprus to the British Empire. Greek and Turkish nationalism among the two major communities of the island (four-fifths of the population being Greek, one-fifth Turkish) were growing, seeking opposite goals. Greeks were demanding enosis (Cyprus to be united with Greece) while Turks were aiming for taksim (partition). In 1955, EOKA, a paramilitary guerilla group, declared its struggle against the British.[1]

In 1960, the British gave in and turned power over to the Greek and Turkish Cypriots. A powersharing constitution was created for the new Republic of Cyprus and included both Turkish and Greek Cypriots holding power. Three treaties were written up to guarantee the integrity and security of the new republic: the Treaty of Establishment, the Treaty of Guarantee and the Treaty of Alliance. According to the constitution, Cyprus was to become an independent republic with a Greek Cypriot president and a Turkish Cypriot vice-president, with full powersharing between Turkish and Greek Cypriots.[2]

Akritas organisation and plan

Akritas organisation (or EOK) was a secret group led by prominent members of the Greek Cypriot community, some of them being cabinet ministers. It was formed in 1961 or 1962, in the eve of the creation of Cyprus Republic, and aimed to achieve enosis.

The plan was an inner document that was publicly revealed in 1966 by pro-Grivas Greek Cypriot newspaper Patris[9] as a response to criticism by pro-Makarios media.[10] It provided a pathway on how to change the constitution of the Cyprus Republic unilaterally, without Turkish Cypriot consent, and to declare enosis with Greece. Because it was expected that Turkish Cypriot would object and revolt, a paramilitary group of several thousand men was formed and began its training.[11][12] According to the copy of the plan, it consisted of two main sections, one delineating external tactics and the other delineating internal tactics. The external tactics pointed to the Treaty of Guarantee as the first objective of an attack, with the statement that it was no longer recognised by Greek Cypriots. If the Treaty of Guarantee was abolished, there would be no legal roadblocks to enosis, which would happen through a plebiscite.[13]

It is unknown who authored the plan or to what extent Makarios was committed to it.

1963 events in Cyprus

In November 1963, Greek Cypriot leader Makarios proposed

Bloody Christmas violence led to the deaths of 364 Turkish Cypriots and 174 Greek Cypriots.[17] Akritas organization's forces took part in the fighting.[18] About a quarter of the Turkish Cypriots, some 25,000 or so, fled their homes and lands and moved into enclaves.[19]

Controversy and opinions

Greek Cypriot sources have accepted the authenticity of the Akritas plan, but controversy regarding its significance and implications persists.[20] It is a subject of debate whether the plan was actually implemented by Makarios. Frank Hoffmeister wrote that the similarity of the military and political actions foreseen in the plan and undertaken in reality was "striking".[15] The Turkish Cypriot perception is that the events of 1963-1964 were part of a policy of extermination.[21] Turkish Cypriot nationalist narratives have presented the plan as a "blueprint for genocide",[20] and it is widely perceived as a plan for extermination among Turkish Cypriots.[22] The Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs calls the plan a "conspiracy to dissolve the Republic of Cyprus, in pre-determined stages and methods, and to bring about the union of Cyprus with Greece".[23]

According to the scholar

See also

- Cyprus

- History of Cyprus

- Modern history of Cyprus

- Timeline of Cypriot history

- Cyprus dispute

- Turkish Cypriot enclaves

- Kokkina exclave

- Cypriot refugees

- Cypriot intercommunal violence

References

- ^ James 2001, pp. 3–9.

- ^ Richter 2011, p. 977-982:The text of the three treaties lies at the appendix pp 988-995

- ^ Chrysostomou 2013, pp. 240.

- ^ Chrysostomou 2013, pp. 248–251.

- ^ Chrysostomou 2013, p. 253.

- ^ Chrysostomou 2013, pp. 257–258.

- ^ Chrysostomou 2013, p. 266.

- ^ Chrysostomou 2013, pp. 267–269.

- ^ Hakki 2007, p. 90: Hakki mentions 1963 as the year that was document revealed but it must be a spelling mistake

- ^ Chrysostomou 2013, p. 273.

- ^ O'Malley & Craig 2001, pp. 90–91.

- ^ Isachenko 2012, p. 41.

- ^ Hakki 2007, pp. 90–97.

- ^ James 2001, p. 36.

- ^ a b c d Hoffmeister 2006, p. 21.

- ^ Chrysostomou 2013, pp. 273–274.

- ^ Oberling 1982, p. 120.

- ^ Chrysostomou 2013, p. 272.

- ^ Kliot 2007; Tocci 2004; Tocci 2007.

- ^ a b Bryant & Papadakis 2012, p. 249.

- ^ Sant-Cassia 2005, p. 23.

- ^ a b Uludağ 2004.

- ^ Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2015.

- ^ Hatzivassiliou 2006, p. 160.

Sources

- Bryant, Rebecca; Papadakis, Yiannis (2012). Cyprus and the Politics of Memory: History, Community and Conflict. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 9781780761077.

- Chrysostomou, Aggelos M. (2013). Από τον Κυπριακό Στρατό μέχρι και τη δημιουργία της Εθνικής Φρουράς (1959-1964) : η διοικητική δομή, στελέχωση, συγκρότηση και οργάνωση του Κυπριακού Στρατού και η δημιουργία ένοπλων ομάδων-οργανώσεων στις δύο κοινότητες (PhD).

- Isachenko, Daria (2012). The Making of Informal States: Statebuilding in Northern Cyprus and Transdniestria. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9780230392069. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- James, Alan (28 November 2001). Keeping the Peace in the Cyprus Crisis of 1963–64. Palgrave Macmillan UK. ISBN 978-1-4039-0089-0.

- Hakki, Murat Metin (2007). The Cyprus Issue: A Documentary History, 1878-2006. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 9781845113926.

- Hatzivassiliou, Evanthis (2006). Greece and the Cold War: Front Line State, 1952-1967. Routledge. p. 160. ISBN 9781134154883.

- Hoffmeister, Frank (2006). Legal Aspects of the Cyprus Problem: Annan Plan And EU Accession. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 9789004152236.

- Kliot, Nurit (2007). "Resettlement of Refugees in Finland and Cyprus: A Comparative Analysis and Possible Lessons for Israel". In Kacowicz, Arie Marcelo; Lutomski, Pawel (eds.). Population resettlement in international conflicts: a comparative study. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-1607-4.

- Oberling, Pierre (1982). The road to Bellapais: The Turkish Cypriot exodus to northern Cyprus. p. 120. ISBN 978-0880330008.

- O'Malley, Brendan; Craig, Ian (25 August 2001). The Cyprus Conspiracy: America, Espionage and the Turkish Invasion. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-86064-737-6.

- Richter, Heinz (2011). Ιστορία της Κύπρου, τόμος δεύτερος(1950-1959). Αθήνα: Εστία.

- Sant-Cassia, Paul (2005). Bodies of Evidence: Burial, Memory and the Recovery of Missing Persons in Cyprus. Berghahn Books. ISBN 9781571816467.

- ISBN 0-7546-4310-7.

- ISBN 978-0-415-41394-7.

- Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2015). "THE "AKRITAS PLAN" AND THE "IKONES" DISCLOSURES OF 1980". Archived from the original on 13 April 2015. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- Uludağ, Sevgül (2004). "Ayın Karanlık Yüzü". Hamamböcüleri Journal. Archived from the original on 23 January 2020. Retrieved 8 April 2015.