Qadi al-Fadil

Muhyi al-Din (or Mujir al-Din) Abu Ali Abd al-Rahim ibn Ali ibn Muhammad ibn al-Hasan al-Lakhmi al-Baysani al-Asqalani, better known by the honorific name al-Qadi al-Fadil (

.Born in

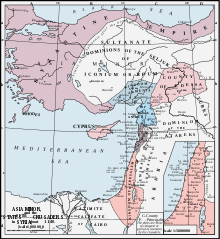

In the new Ayyubid regime, Qadi al-Fadil was an important figure, serving as Saladin's chief counsellor. He was left in charge of the Egyptian administration during Saladin's wars in the Levant. As a result, historians often attribute to him the title of vizier, which he never held. After Saladin's death in 1193, Qadi al-Fadil served Saladin's son al-Afdal, ruler of Damascus, before switching his allegiance to Saladin's second son, al-Aziz, ruler of Egypt. He retired after 1195, and died in 1200.

Qadi al-Fadil's reputation among contemporaries and later generations rests chiefly on his skill as an

Life

Service under the Fatimids

Qadi al-Fadil was born on 2 April 1135 at

Qadi al-Fadil received his basic education at his home town,

According to the 13th-century encyclopaedist

When Ruzzik was deposed by Shawar, Qadi al-Fadil became the secretary to Shawar's son, Kamil.[3] During Shawar's conflicts with Dirgham, he sided with the former, and was even imprisoned for a time along with Kamil in August 1163, when Dirgham seized power. After the final victory of Shawar in May 1164, Qadi al-Fadil was released and given many honours, including the epithet of al-Fadil (lit. 'the Excellent/Virtuous One'), by which he is known.[2][12]

Switch of allegiance and the fall of the Fatimid Caliphate

|

| Part of a series on |

| Saladin |

|---|

As a partisan of Shawar, Qadi al-Fadil had originally opposed

This change is not difficult to understand. Although a high official of the Fatimid state, Qadi al-Fadil was likely a devoted Sunni, as were most of the civilian bureaucracy at the time. His loyalty to the Fatimid dynasty and the Isma'ili sect was therefore dubious at best, and it was not difficult for him to transfer his allegiance to the Sunni Ayyubids.

In 1167/8, Qadi al-Fadil became the new head of the chancery, replacing his old patron Ibn Khallal. When the latter died on 4 March 1171, he became the secretary to Saladin.[3] From 1170 on, Saladin gradually moved to dismantle the Fatimid regime and replace Isma'ilism with Sunni Islam.[17][18] The 14th-century Egyptian historian al-Maqrizi ascribes to Saladin and Qadi al-Fadil jointly the common cause of deposing the Fatimid dynasty,[19] and Saladin himself is said to have remarked "I took Egypt not by force of arms but by the pen of Qadi al-Fadil".[2][20]

When Saladin deposed the Fatimid regime outright following the death of caliph al-Adid in September 1171, Qadi al-Fadil played a leading role in carrying out the subsequent changes in the military and fiscal administration of Egypt.[3] Qadi al-Fadil's role in the suppression of a supposed pro-Fatimid conspiracy in April 1174 is unclear. The aftermath included the execution of a number of former Fatimid officials, most notably the poet Umara ibn Abi al-Hasan al-Yamani. Qadi al-Fadil's account of the extent of the conspiracy is at odds with the limited reprisals, and the affair was likely a settling of old rivalries within the former Fatimid administrative elites.[21]

Service under Saladin

Imad al-Din al-Isfahani, a friend and collaborator who entered Saladin's service through Qadi al-Din's intercession,[22] writes of him that he was the "principal driving force behind the affairs of Saladin's regime", but his exact duties are unclear.[23] Although often called Saladin's vizier, Qadi al-Fadil never held that title. He was nevertheless the closest counsellor and chief secretary of the Ayyubid ruler until Saladin's death.[2][3] He accompanied Saladin in his campaigns in Syria,[3] but in the sources, he is chiefly associated with Egypt, where most of his career took place. Thus in 1188/89 Saladin renewed Qadi al-Fadil's brief to supervise all affairs of Egypt, while in 1190/91 he was tasked with equipping a fleet to assist Saladin in his Siege of Acre.[23]

At the same time, during Saladin's absence in the wars against the Crusaders, the government of Egypt was formally left to other members of the Ayyubid clan. Qadi al-Fadil was critical of Saladin's brother, al-Adil. After he left Egypt, Qadi al-Fadil successfully lobbied for al-Adil's replacement by his friend, Saladin's nephew Taqi al-Din.[24] For unknown reasons, Qadi al-Fadil was not present at Saladin's greatest victory at the Battle of Hattin (1187), nor in the subsequent recapture of Jerusalem.[25]

In Christian sources, Qadi al-Fadil is blamed for the anti-dhimmi purge of the early years of Saladin's rule, which saw Christians evicted and banned from holding posts in the public fiscal administration.[26] At the same time, however, Qadi al-Fadl sponsored a number of Jewish physicians, among them the celebrated philosopher Maimonides, whom he defended from charges of apostasy,[27][28] and who dedicated his book On Poisons and Antidotes to his patron.[1]

From his prominent post, Qadi al-Fadil became a wealthy man: he reportedly received an annual salary of 50,000 gold dinars, and became a successful merchant, trading with India and North Africa.

Final years and death

After Saladin's death at Damascus in March 1193, Qadi al-Fadil initially served his oldest son al-Afdal, ruler of Damascus. Due to al-Afdal's erratic leadership, he quickly returned to Egypt, where he entered the service of al-Aziz, Saladin's second son, who had seized power there.[3][25] When the two brothers came into conflict, Qadi al-Fadil managed to mediate a peace between them in 1195.[3] After this he retired, and died on 26 January 1200.[2][3] He was buried in the Qarafa cemetery in Cairo. A mausoleum was erected on top of his grave.[25]

Qadi al-Fadil's surviving family is mostly obscure. From his many sons, only al-Qadi al-Ashraf Ahmad Abu'l-Abbas is notable, who served the Ayyubid rulers of Egypt until his death in 1245/46.[29]

Writings and patronage of learning

Already during his lifetime, Qadi al-Fadil was highly esteemed, chiefly due to the "exceptional quality of his private and official epistolary style", which was praised, held up as a model, and emulated by subsequent generations of writers.[3] This style was similar to that of Imad al-Din al-Isfahani, and "combines richness (perhaps a little less prolix) and suppleness of form with a realistic treatment of the facts, a lesson too often forgotten by later writers, which makes his correspondence a valuable historical source".[3] Al-Isfahani himself praises his contemporary as the "lord of word and pen", and writes that just as the Sharia invalidated all previous laws, so Qadi al-Fadil's style overrode all previous traditions in epistle literature (insha).[27] As a result, many of his chancery epistles were included in the works of other authors, from chroniclers such as al-Isfahani and Abu Shama to compilers of insha literature, most notably al-Qalqashandi.[3] Others survive as manuscripts to this day, and the work of editing and publishing them is still ongoing.[3][27] However, they still represent only a part of the reportedly 100 volumes of official and private correspondence attributed to him.[27]

As head of the chancery, Qadi al-Fadil also kept an official diary (known as Mutajaddidat or Majarayat). It has not survived, apart from several extracts from it that have been included in later histories, notably al-Maqrizi, and is an invaluable source on Saladin's rule in Egypt.[3][27][31] According to the 13th-century historian Ibn al-Adim, however, this diary was actually kept by a different historian, Abu Ghalib al-Shaybani.[3]

Qadi al-Fadil was also active as a poet. Many of his works are included in his epistles. His collected poems were published in two volumes in Cairo in 1961 and 1969, edited by Ahmad A. Badawi and Ibrahim al-Ibyari.[27][32]

A famous bibliophile, Qadi al-Fadil amassed a large library, much of which he donated to a

References

- ^ a b Kraemer 2005, p. 31.

- ^ a b c d e f Şeşen 2001, p. 114.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Brockelmann & Cahen 1978, p. 376.

- ^ Lev 1999, p. 14.

- ^ Lev 1999, pp. 14–15, 19.

- ^ a b Lev 1999, p. 15.

- ^ Lev 1999, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Lev 1999, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Lev 1999, pp. 14, 20.

- ^ Lev 1999, pp. 16–17.

- ^ a b Lev 1999, p. 17.

- ^ Lev 1999, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Lev 1999, p. 21.

- ^ Lev 1999, pp. 18–19, 21.

- ^ Lev 1999, pp. 17–19, 78.

- ^ Brett 2017, pp. 276–277, 280ff..

- ^ Brett 2017, p. 293.

- ^ Lev 1999, pp. 84–86.

- ^ Lev 1999, p. 86.

- ^ Lev 1999, p. 92.

- ^ Lev 1999, pp. 86–94.

- ^ Lev 1999, pp. 29–30.

- ^ a b Lev 1999, p. 22.

- ^ Lev 1999, pp. 22–23.

- ^ a b c Lev 1999, p. 23.

- ^ Lev 1999, p. 188.

- ^ a b c d e f g Şeşen 2001, p. 115.

- ^ Lev 1999, pp. 189–190.

- ^ a b Lev 1999, p. 24.

- ^ Lev 1999, p. 114.

- ^ Lev 1999, pp. 25, 43.

- ^ Brockelmann & Cahen 1978, pp. 376–377.

- ^ a b Lev 1999, p. 128.

Sources

- Brett, Michael (2017). The Fatimid Empire. The Edinburgh History of the Islamic Empires. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-4076-8.

- Brockelmann, C. & Cahen, Cl. (1978). "al-Ḳāḍī al-Fāḍil". In OCLC 758278456.

- Kraemer, Joel L. (2005). "Maimonides: An Intellectual Portrait". In Seeskin, Kenneth (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Maimonides. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 10–57. ISBN 978-0-521-52578-7.

- Lev, Yaacov (1999). Saladin in Egypt. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 90-04-11221-9.

- Şeşen, Ramazan (2001). "Kādî el-Fâzıl". TDV Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 24 (Kāânî-i Şîrâzî – Kastamonu) (in Turkish). Istanbul: ISBN 978-975-389-451-7.

Further reading

- Helbig, Adolph H. (1908). Al-Qāḍi al-Fāḍil, der Wezīr Saladin's. Eine Biographie (PhD dissertation) (in German). Leipzig: W. Drugulin.

- S2CID 211952166.

- Jackson, D. (1995). "Some Preliminary Refections on the Chancery Correspondence of the Qadi al-Fadil". In Vermeulen, U.; De Smet, D. (eds.). Egypt and Syria in the Fatimid, Ayyubid and Mamluk Eras, Part 1. Louvain: Peeters Publishers. pp. 207–218. ISBN 90-6831-683-4.