Albanians in Egypt

الألبان في مصر Shqiptarët e Egjiptit | |

|---|---|

| [1] | |

| Languages | |

| Albanian, Egyptian Arabic | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly : Sunni Islam Minority : Bektashi Order | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Albanians, Albanian diaspora |

| Part of a series on |

| Albanians |

|---|

|

| By country |

|

|

Culture |

|

| Religion |

|

| Languages and dialects |

The

History

Ottoman Era

In 1517, Egypt became a province of the

During and after the

Muhammad Ali Era

Muhammad Ali was an Albanian commander in the

Muhammad Ali transformed Egypt into a regional power. He saw Egypt as the natural successor to the decaying Ottoman Empire, and subsequently constructed a military state with 4% of the populace serving in the army, which put Egypt on equal footing with the Ottoman Empire. His transformation of Egypt would be echoed by the later strategies used by the Soviet Union to establish itself as a modern industrial power.[5] Muhammad Ali summed up his vision for Egypt in this way:

I am well aware that the [Ottoman] Empire is heading by the day toward destruction. ... On her ruins I will build a vast kingdom ... up to the Euphrates and the Tigris.

— Georges Douin, ed., Une Mission militaire française auprès de Mohamed Aly, correspondance des Généraux Belliard et Boyer (Cairo: Société Royale de Géographie d'Égypte, 1923), p.50

At the height of his power, Muhammad Ali and his son

The island of

Khedivate and British occupation

Though Muhammad Ali and his descendants used the title of

In defiance of the Egyptians, the British proclaimed Sudan to be an Anglo-Egyptian Condominium, a territory under joint British and Egyptian rule rather than an integral part of Egypt. This was continually rejected by Egyptians, both in government and in the public at large, who insisted on the "unity of the Nile Valley", and would remain an issue of controversy and enmity between Egypt and Britain until Sudan's independence in 1956.

Sultanate and Kingdom

In 1914, Khedive

Dissolution

The reign of Farouk was characterized by ever increasing nationalist discontent over the British occupation, royal corruption and incompetence, and the disastrous

Albanian National Awakening and early 20th century

Nationalist figures and writers such as Thimi Mitko,

In 1907, with the initiative of Mihal Turtulli, Jani Vruho, and Thanas Tashko, the Albanian community send a promemorium to the

Up to the 1940s the Kingdom of Egypt continued to recruit ethnic Albanians from the Balkans in order to place them in key civil service positions. Recruitment criteria besides the appropriate qualification were exclusively Albanian language and ethnicity, and not religion.[6]

Discrimination

A few Albanians kept coming to Egypt throughout

Famous Albanians of Egypt

In art

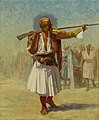

In 1856, the

-

Egyptian Recruits Crossing the Desert, 1857.

-

Albanian guards playing dice, 1859.

-

Albanian Guard in Cairo, 1861.

-

A Joke – An Albanian Blowing Smoke into his Dog's Nose, 1864.

-

Prayer in the Desert, 1864.

-

An Albanian on his donkey crossing the desert, unknown date.

-

An Albanian with his Dog, 1865.

-

An Albanian with Two Whippets, 1867.

-

An Albanian Smoking, 1868.

-

Bashi-Bazouk Singing, 1868.

-

An Albanian Bashi-Bazouk, 1896.

-

Bashi-Bazouk Chieftain, 1881

-

An Albanian officer crossing the desert with Egyptian recruits, 1894.

See also

- Albanians in Greece

- Albanians in Turkey

- Ashkali and Balkan Egyptians

- Ottoman Albania

- Sufism

- Muhammad Ali dynasty

- Muhammad Ali of Egypt

- Albania–Egypt relations

References

Citations

- ^ a b Saunders 2011, p. 98. "Egypt also lays claim to some 18,000 Albanians, supposedly lingering remnants of Mohammad Ali's army."

- ^ Winter 2004, p. 35.

- ^ a b Öztuna 1979, p. 51.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Uran Asllani (2006-06-05), Shqiptarët e egjiptit dhe veprimtaria atdhetare e tyre [Albanians of Egypt and their patriotic activity] (in Albanian), Gazeta Metropol

- ISBN 9781107507180.

- ^ ISSN 0288-3503.

- ^ a b c Norris 1993, pp. 209–210. "This was an age when Albanians and Bosnians were posted to garrisons within the Nile regions, and furthermore the bulk of the Albanian troops were uncultured, exceedingly unruly, and often hated. Yet the dynasty that Muhammad ‘Alī established, the affection it had for Albanians and received from them, and the haven it afforded to them as exiles from Ottoman control, victimisation by Greek neighbours, or the sheer misery of Balkan poverty, meant that in time Alexandria, Cairo, Beni Suef and other Egyptian towns would harbour Albanians who organised associations, published newspapers and above all wrote works in verse and prose that include significant masterpieces of modern Albanian literature. Within al-Azhar and the two Baktāshi tekkes in Cairo, Qaṣr al-’Aynī and Kajgusez Abdullah Megavriu, Albanians and Balkan contemporaries were to find inspiration for a mystical quest, and artistic and literary stimulus, that sent ripples, as on a pond, throughout Albanian and Egyptian circles in Cairo and distantly and remotely in towns of Albania, Kosovo and Macedonia. Some of the outstanding literary figures of modern Albanian literature — for example, Thimi Mitko (d. 1890), the author of collections of Albanian folksongs, folk-tales and sayings, in his The Albanian Bee (Bleta Shqypëtare), Spiro Dine (d. 1922) in his Waves of the Sea (Valët e detit) and Andon Zako Çajupi (1866-1930) in his Baba Tomorri (Cairo, 1902) and his Skanderbeg drama — although they lived in Egypt for much of their lives, were essentially nationalists and not much influenced by the Islamic way of life that they saw around them. If anything, the rural arid peasant life in Egypt acted as a spur to their absorption in popular traditions which, in their view, enshrined the soul of their people. The Albanians in Egypt were, without a doubt, influenced by the Egyptian theatre — but specifically by those elements not overtly infused with Islamic sentiments. Later writers became prominent figures among the Albanian community in Cairo. Milo Duçi (Duqi) (d. 1933) did so because of his office as president of the national ‘Brethren’ league (Villazëria/Ikhwa), and by his Albanian newspapers (al-‘Ahd, 1900, known in Egypt as al-Aḥādīth, 1925). He also wrote plays, especially ‘The Saying’ (E Thëna, 1922) and ‘The Bey's Son’ (1923), and a novel Midis dy grash (Between two women, 1923). More recently still, it has been secular and Arab nationalist causes such as Palestine and Algeria that have inspired Albanian Egyptian writers."

- ^ Fraser 2014, p. 92.

- ^ Carstens 2014, p. 753.

- ^ University of Wisconsin 2002, p. 130.

- ^ Fahmy 2002, p. 40, 89.

- ^ Fahmy 2012, p. 30.

- ^ Cummins 2009, p. 60.

- ^ Skoulidas 2013. para. 15, 22, 25, 28.

- ^ a b Elsie 2010, pp. 125–126.

- ^ Elsie 2010, p. 111.

- ^ a b Blumi 2012, pp. 131–132.

- ^ Blumi 2011, p. 205.

- ^ Trix 2009, p. 107.

- ^ Curtis 2010, p. 83.

- ^ Elsie, Robert. "Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904)". albanianart.net.

Sources

- Blumi, Isa (2011). Reinstating the Ottomans, Alternative Balkan Modernities: 1800–1912. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. ISBN 9780230119086.

- Blumi, Isa (2012). Foundations of Modernity: Human Agency and the Imperial State. New York: Routledge. ISBN 9780415884648.

- Carstens, Patrick Richard (2014). The Encyclopædia of Egypt during the Reign of the Mehemet Ali Dynasty 1798-1952: The People, Places and Events that Shaped Nineteenth Century Egypt and its Sphere of Influence. Victoria: FriesenPress. ISBN 9781460248980.

- Cummins, Joseph (2009). The War Chronicles: From Flintlocks to Machine Guns. Beverly: Fair Winds. ISBN 9781616734046.

- Curtis, Edward E. (2010). Encyclopedia of Muslim-American History. New York: Infobase Publishing. ISBN 9781438130408.

- Elsie, Robert (2010). Historical Dictionary of Albania. Lanham: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810873803.

- Fahmy, Khaled (2002). All the Pasha's men: Mehmed Ali, his army and the making of modern Egypt. Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 9789774246968.

- Fahmy, Khaled (2012). Mehmed Ali: From Ottoman Governor to Ruler of Egypt. New York: Oneworld Publications. ISBN 9781780742113.

- Fraser, Kathleen W. (2014). Before They Were Belly Dancers: European Accounts of Female Entertainers in Egypt, 1760-1870. Jefferson: McFarland. ISBN 9780786494330.

- Norris, Harry Thirlwall (1993). Islam in the Balkans: religion and society between Europe and the Arab world. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press. p. 249. ISBN 9780872499775.

Albanians Arnaout Syria.

- Öztuna, Yılmaz (1979). Başlangıcından zamanımıza kadar büyük Türkiye tarihi: Türkiye'nin siyasî, medenî, kültür, teşkilât ve san'at tarihi. Istanbul: Ötüken Yayınevi. ISBN 975-437-141-5.

- Saunders, Robert A. (2011). Ethnopolitics in Cyberspace: The Internet, Minority Nationalism, and the Web of Identity. Lanham: Lexington Books. ISBN 9780739141946.

- Skoulidas, Elias (2013). "The Albanian Greek-Orthodox Intellectuals: Aspects of their Discourse between Albanian and Greek National Narratives (late 19th - early 20th centuries)". Hronos. 7. Archived from the original on 2019-09-23. Retrieved 2014-12-26.

- Trix, Frances (2009). The Sufi Journey of Baba Rexheb. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9781934536544.

- University of Wisconsin (2002). "International Journal of Turkish Studies". International Journal of Turkish Studies. 8 (1/2).

- Winter, Michael (2004). Egyptian society under Ottoman rule, 1517-1798. New York: Routledge. ISBN 9781134975136.