Albert R.N.

| Albert R.N. | |

|---|---|

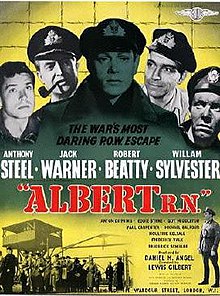

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Lewis Gilbert |

| Written by | |

| Based on | play by Guy Morgan and Edward Sammis |

| Produced by | Daniel M. Angel |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Jack Asher |

| Edited by | Charles Hasse |

| Music by | Malcolm Arnold |

Production company | Angel Productions |

| Distributed by | Eros Films |

Release date | 23 November 1953 |

Running time | 88 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | £88,378[1][2] |

Albert R.N. is a 1953 British war film directed by Lewis Gilbert and starring Jack Warner, Anthony Steel and Robert Beatty.

Plot

An escape tunnel for the naval officer prisoners during the

Lieutenant Ainsworth devises a scheme with the escape committee to use the components of a mannequin named Albert to convince the Germans that all prisoners sent outside the camp for a bathhouse wash up are returned to the camp. A piece of Albert is smuggled with the prisoners going to the bathhouse and reassembled for the return. Ainsworth also has a woman pen pal he has never seen; he plans to marry her once he is free. Though the originator has the right to try out his own idea, Ainsworth insists that his hut mates draw cards for the privilege; Erickson wins and gets away.

After waiting a while, they decide to reuse the ploy. This time, Ainsworth's friend, after hearing that his pen pal has not written in a while, sees to it that the draw is rigged so that he wins. Ainsworth auctions his place, only to have Captain Maddox, the senior prisoner of war, order him to go. Ainsworth is recaptured the same day. Later, the camp commandant informs the men that Erickson was shot while resisting arrest by the Gestapo; his ashes are handed over.

When SS Hauptsturmführer Schultz expresses interest in American Lieutenant "Texas" Norton's chronometer, Norton notes Schultz is in charge of the camp's boundary lights and asks him to see that they malfunction during the next Allied night bombing raid but it is a trap. Schultz signals his men to turn the lights back on while Norton is cutting through the barbed wire fence, then shoots him down in cold blood.

Schultz tries to suborn Ainsworth but Ainsworth tells him he will see to it he is prosecuted for murder after the war. When Schultz becomes the new Kommandant, Ainsworth insists on trying to escape again, using Albert. He gets away but waits at night to confront Schultz outside the camp. After a struggle, he gets Schultz's pistol. When Allied bombs drop uncomfortably close by, Schultz runs for it. Ainsworth is unable to bring himself to shoot the fleeing German in the back but a bomb kills him. Ainsworth takes back Norton's chronometer from the dead man and walks away.

Cast

- Jack Warner as Captain Maddox

- Anthony Steel as Lieutenant Geoffrey Ainsworth

- Robert Beatty as Lieutenant Jim Reed

- William Sylvester as Lieutenant Texas Norton

- Heerequivalent in the credits)

- Michael Balfour as Lieutenant Henry Adams

- Guy Middleton as Captain Barton

- Paul Carpenter as Lieutenant Fred Erickson

- Moultrie Kelsall as Commander Henry Dawson

- Eddie Byrne as Commander Joe Brennan

- Geoffrey Hibbert as Lieutenant Cutter Craig

- Peter Jones as Lieutenant Schoolie Browne

- Frederick Valk as Camp Kommandant

- Frederick Schiller as Herman

- Walter Gotell as Feldwebel

- Peter Swanwick as Obergefreiter

Historical background

The film is based on a true story. "Albert R.N." was a dummy constructed in Marlag O, the prisoner of war camp in northern Germany for naval officers. The head was sculpted by war artist John Worsley (1919–2000), the body by Lieutenant Bob Staines RNVR, and Lieutenant-Commander Tony Bentley-Buckle devised a mechanism enabling Albert's eyes to blink and move, adding realism to the dummy.[3] "Albert" was used as a stand-in for a head count while a prisoner escaped and was used on two occasions.[4] In the first attempt Lieutenant William "Blondie" Mewes RNVR escaped from the camp shower block and the skilful use of "Albert" during roll-calls gave him four days head start before a missing PoW was reported. Mewes was recaptured in Lübeck and returned to Marlag camp. The second occasion failed when the escaping PoW was discovered hiding in the camp shower block and "Albert" was discovered in the subsequent searches.[5]

Worsley made a new "Albert" for use in the film. Senior Commissioned Gunner (TAS) Lieutenant John William Goble RN aided Worsley in the development of "Albert" in the POW camp, Marlag O and acted as technical adviser for the film. Worsley made a third "Albert" for the retrospective exhibition of his work held in

Production

The film was first planned as a project for

Release

Lewis Gilbert said the film earned its money back in the United Kingdom.[1] Variety on 21 October 1953, page 181, described it as "Well-done British-made prison meller, lacks names for U.S. market", and went on to say, "A solid all-round cast admirably fits into the plot. Anthony Steel handsomely suggests the young artist responsible for the creation of 'Albert' and Jack Warner is reliably cast as the senior British officer who maintains discipline with understanding in the camp. Robert Beatty, William Sylvester and Guy Middleton are among the principal POWs. Frederick Valk is a sympathetic camp commandant, but Anton Diffring suggests the typical ruthless Nazi type."[10][full citation needed]

References

- ^ a b c Brian MacFarlane, An Autobiography of British Cinema, Methuen 1997 p. 220

- ^ Chapman, J. (2022). The Money Behind the Screen: A History of British Film Finance, 1945-1985. Edinburgh University Press p 358

- ^ Daily Telegraph obituary: Lieutenant-Commander Tony Bentley-Buckle

- ^ Steve Holland, 'John Worsley: Energetic artist who drew a debonair police hero for the Eagle comic, and created Albert RN, the dummy hero of a famed wartime escape', The Guardian, 13 October 2000 accessed 11 July 2012

- ISBN 978-1-85310-257-8.

- The Mail. Adelaide: National Library of Australia. 13 September 1952. p. 7 Supplement: SUNDAY MAGAZINE. Retrieved 11 July 2012.

- ^ 'Slapstick' Will Tell Big Comedy Saga; Tufts Builds British Career Schallert, Edwin. Los Angeles Times 12 January 1953: B9.

- ^ Vagg, Stephen (23 September 2020). "The Emasculation of Anthony Steel: A Cold Streak Saga". Filmink.

- The Mail. Adelaide: National Library of Australia. 17 October 1953. p. 60. Retrieved 11 July 2012.

- ^ Review of film at Variety

External links

- Albert RN at IMDb