Alexander Cunningham

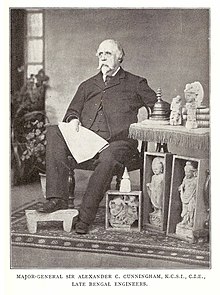

Sir Alexander Cunningham | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 23 January 1814 |

| Died | 28 November 1893 (aged 79) London, United Kingdom |

| Nationality | British |

| Occupations |

|

| Spouse |

Alicia Maria Whish (m. 1840)Peter Cunningham (brother)[1] |

He wrote numerous books and monographs and made extensive collections of artefacts. Some of his collections were lost, but most of the gold and silver coins and a fine group of

Early life and career

Cunningham was born in London in 1814 to the

From 1836 to 1840 he was

Military life

In 1841 Cunningham was made executive engineer to the

In 1846, he was made commissioner along with

In 1856 he was appointed chief engineer of

Archaeology

Cunningham had taken a keen interest in antiquities from early on in his career. Following the activities of Jean-Baptiste Ventura (general of Ranjit Singh)—who, inspired by the French explorers in Egypt, had excavated the bases of pillars to discover large stashes of Bactrian and Roman coins—excavations became a regular activity among British antiquarians.[9]

In 1834 he submitted to the

By 1851, he also began to communicate with William Henry Sykes and the East India Company on the value of an archaeological survey. He provided a rationale for providing the necessary funding, arguing that the venture[9]

... would be an undertaking of vast importance to the Indian Government politically, and to the British public religiously. To the first body it would show that India had generally been divided into numerous petty chiefships, which had invariably been the case upon every successful invasion; while, whenever she had been under one ruler, she had always repelled foreign conquest with determined resolution. To the other body it would show that Brahmanism, instead of being an unchanged and unchangeable religion which had subsisted for ages, was of comparatively modern origin, and had been constantly receiving additions and alterations; facts which prove that the establishment of the Christian religion in India must ultimately succeed.[10]

Following his retirement from the Royal Engineers in 1861,

Most antiquarians of the 19th century who took interest in identifying the major cities mentioned in ancient Indian texts, did so by putting together clues found in classical Graeco-Roman chronicles and the travelogues of travellers to India such as

Now as Hwen Thsang, on his return to China, was accompanied by laden elephants, his three days' journey from Takhshasila [

Manikyala tope, twenty-eight monasteries, and nine temples.— Alexander Cunningham, [14]

After his department was abolished in 1865, Cunningham returned to England and wrote the first part of his Ancient Geography of India (1871), covering the Buddhist period; but failed to complete the second part, covering the Muslim period.

Numismatic interests

Cunningham assembled a large

Family and personal life

Two of Cunningham's brothers,

Cunningham married Alicia Maria Whish, daughter of Martin Whish, B.C.S., on 30 March 1840. The couple had two sons, Lieutenant-Colonel

Cunningham died on 28 November 1893 at his home in South Kensington and was buried at Kensal Green Cemetery, London. His wife had predeceased him. He was survived by his two sons.[1]

Awards and memorials

Cunningham was awarded the CSI on 20 May 1870 and CIE in 1878. In 1887, he was made a Knight Commander of the Order of the Indian Empire.[15]

Publications

Books written by Cunningham include:

- LADĀK: Physical, Statistical, and Historical with Notices of the Surrounding Countries (1854).

- Bhilsa Topes (1854), a history of Buddhism

- The Ancient Geography of India (1871)

- Archaeological Survey Of India Vol. 1 (1871) Four Reports Made During the Years, 1862-63-64-65, Volume 1 (1871)

- Archaeological Survey Of India Vol. 2

- Archaeological Survey Of India Vol. 3 (1873)

- Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum. Volume 1. (1877)

- The Stupa of Bharhut: A Buddhist Monument Ornamented with Numerous Sculptures Illustrative of Buddhist Legend and History in the Third Century B.C. (1879)

- The Book of Indian Eras (1883)

- Coins of Ancient India (1891)

- Mahâbodhi, or the great Buddhist temple under the Bodhi tree at Buddha-Gaya (1892)

- Coins of Medieval India (1894)

- Report of Tour in Eastern Rajputana

Additional works:

- The World of India’s First Archaeologist: Letters from Alexander Cunningham to J.D.M. Beglar; Oxford University Press: Upinder Singh.

- Imam, Abu (1963). Sir Alexander Cunningham and the Beginnings of Indian Archeology (Thesis). OCLC 966141480.

Citations

- ^ doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/6916. (Subscription or UK public library membershiprequired.)

- ^ Buckland 1906, p. 106.

- ^ Kejariwal 1999, p. 200.

- ^ Vibart 1894, pp. 455–59.

- ^ Waller 2004, p. 13.

- ^ Strachey 1854, p. 3.

- ^ Cunningham 1854b, p. ?.

- ^ Cunningham 1854a, p. ?.

- ^ S2CID 163154105.

- ^ Cunningham 1843, pp. 241–47.

- ^ Cunningham 1871c, pp. 1–3.

- ^ Cunningham 1848, pp. 13–60.

- ^ Singh 2008, p. 265.

- ^ Cunningham 1871c, p. 105.

- ^ a b Cunningham 1871c, p. ?.

- ^ Iman 1966, p. 191.

- ^ Mathur 2007, p. 146.

- ^ Cunningham 1853, pp. 12–14.

References

- Buckland, Charles Edward (1906). Dictionary of Indian Biography. London: Swan Sonnenschein & Co.

- Cunningham, Alex (July 1843). "An Account of the Discovery of the Ruins of the Buddhist City of Samkassa". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 7 (14): 241–249. S2CID 162756981.

- Cunningham, Alexander (1848). "Verification of the Itinerary of the Chinese Pilgrim, Hwan Thsang, through Afghanistan and India during the First Half of the Seventh Century of the Christian Era". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal. 17 (2).

- Cunningham, Joseph Davey (1853) [1849]. Garrett, Herbert Leonard Offley (ed.). Cunningham's History of the Sikhs (2 ed.). John Murray.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Cunningham, Alexander (1871). Archaeological Survey of India: four reports made during the years 1862–63–64–65. Shimla: Government Central Press.

- Cunningham, Alexander (1871). Four Reports Made During the Years, 1862-63-64-65. Vol. I. Shimla: Government Central Press.

- Cunningham, Alexander (1871). The Ancient Geography of India. Vol. 1. London: Trübner and Co.

- Cunningham, Alexander (1854). The Bhilsa Topes, Or, Buddhist Monuments of Central India: Comprising a Brief Historical Sketch of the Rise, Progress and Decline of Buddhism. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Cunningham, Alexander (1854). Ladak, physical, statistical and historical. London: W. H. Allen.

- Cunningham, Alexander (1871). The Ancient Geography of India: The Buddhist Period, Including the Campaigns of Alexander, and the Travels of Hwen-Thsang. Cambridge, NY: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781108056458.

- Iman, Abu (1966). Sir Alexander Cunningham and the beginnings of Indian archaeology. Dacca: Asiatic Society of Pakistan.

- Kejariwal, O. P. (1999). The Asiatic Society of Bengal and the Discovery of India's Past 1784–1838 (1988 ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19565089-1.

- Mathur, Saloni (2007). India by Design: Colonial History and Cultural Display. University of California Press.

- ISBN 9788131711200.

- Strachey, Henry (1854). Physical Geography of Western Tibet. London: William Clowes and sons.

- Vibart, H. M. (1894). Addiscombe: its heroes and men of note. Westminster: Archibald Constable.

- Waller, Derek J. (2004). The Pundits: British Exploration of Tibet and Central Asia. University Press of Kentucky.