Algebraic geometry

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2020) |

plane |

|---|

| Geometers |

Algebraic geometry is a branch of

The fundamental objects of study in algebraic geometry are

Algebraic geometry occupies a central place in modern mathematics and has multiple conceptual connections with such diverse fields as complex analysis, topology and number theory. As a study of systems of polynomial equations in several variables, the subject of algebraic geometry begins with finding specific solutions via equation solving, and then proceeds to understand the intrinsic properties of the totality of solutions of a system of equations. This understanding requires both conceptual theory and computational technique.

In the 20th century, algebraic geometry split into several subareas.

- The mainstream of algebraic geometry is devoted to the study of the complex points of the algebraic varieties and more generally to the points with coordinates in an algebraically closed field.

- Real algebraic geometry is the study of the real algebraic varieties.

- .

- A large part of singularity theory is devoted to the singularities of algebraic varieties.

- Computational algebraic geometry is an area that has emerged at the intersection of algebraic geometry and computer algebra, with the rise of computers. It consists mainly of algorithm design and software development for the study of properties of explicitly given algebraic varieties.

Much of the development of the mainstream of algebraic geometry in the 20th century occurred within an abstract algebraic framework, with increasing emphasis being placed on "intrinsic" properties of algebraic varieties not dependent on any particular way of embedding the variety in an ambient coordinate space; this parallels developments in topology,

Basic notions

Zeros of simultaneous polynomials

In classical algebraic geometry, the main objects of interest are the vanishing sets of collections of

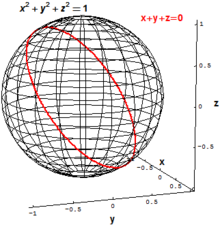

A "slanted" circle in R3 can be defined as the set of all points (x,y,z) which satisfy the two polynomial equations

Affine varieties

First we start with a field k. In classical algebraic geometry, this field was always the complex numbers C, but many of the same results are true if we assume only that k is algebraically closed. We consider the affine space of dimension n over k, denoted An(k) (or more simply An, when k is clear from the context). When one fixes a coordinate system, one may identify An(k) with kn. The purpose of not working with kn is to emphasize that one "forgets" the vector space structure that kn carries.

A function f : An → A1 is said to be polynomial (or regular) if it can be written as a polynomial, that is, if there is a polynomial p in k[x1,...,xn] such that f(M) = p(t1,...,tn) for every point M with coordinates (t1,...,tn) in An. The property of a function to be polynomial (or regular) does not depend on the choice of a coordinate system in An.

When a coordinate system is chosen, the regular functions on the affine n-space may be identified with the ring of

We say that a polynomial vanishes at a point if evaluating it at that point gives zero. Let S be a set of polynomials in k[An]. The vanishing set of S (or vanishing locus or zero set) is the set V(S) of all points in An where every polynomial in S vanishes. Symbolically,

A subset of An which is V(S), for some S, is called an algebraic set. The V stands for variety (a specific type of algebraic set to be defined below).

Given a subset U of An, can one recover the set of polynomials which generate it? If U is any subset of An, define I(U) to be the set of all polynomials whose vanishing set contains U. The I stands for ideal: if two polynomials f and g both vanish on U, then f+g vanishes on U, and if h is any polynomial, then hf vanishes on U, so I(U) is always an ideal of the polynomial ring k[An].

Two natural questions to ask are:

- Given a subset U of An, when is U = V(I(U))?

- Given a set S of polynomials, when is S = I(V(S))?

The answer to the first question is provided by introducing the Zariski topology, a topology on An whose closed sets are the algebraic sets, and which directly reflects the algebraic structure of k[An]. Then U = V(I(U)) if and only if U is an algebraic set or equivalently a Zariski-closed set. The answer to the second question is given by Hilbert's Nullstellensatz. In one of its forms, it says that I(V(S)) is the radical of the ideal generated by S. In more abstract language, there is a Galois connection, giving rise to two closure operators; they can be identified, and naturally play a basic role in the theory; the example is elaborated at Galois connection.

For various reasons we may not always want to work with the entire ideal corresponding to an algebraic set U. Hilbert's basis theorem implies that ideals in k[An] are always finitely generated.

An algebraic set is called irreducible if it cannot be written as the union of two smaller algebraic sets. Any algebraic set is a finite union of irreducible algebraic sets and this decomposition is unique. Thus its elements are called the irreducible components of the algebraic set. An irreducible algebraic set is also called a variety. It turns out that an algebraic set is a variety if and only if it may be defined as the vanishing set of a prime ideal of the polynomial ring.

Some authors do not make a clear distinction between algebraic sets and varieties and use irreducible variety to make the distinction when needed.

Regular functions

Just as

It may seem unnaturally restrictive to require that a regular function always extend to the ambient space, but it is very similar to the situation in a normal topological space, where the Tietze extension theorem guarantees that a continuous function on a closed subset always extends to the ambient topological space.

Just as with the regular functions on affine space, the regular functions on V form a ring, which we denote by k[V]. This ring is called the

Since regular functions on V come from regular functions on An, there is a relationship between the coordinate rings. Specifically, if a regular function on V is the restriction of two functions f and g in k[An], then f − g is a polynomial function which is null on V and thus belongs to I(V). Thus k[V] may be identified with k[An]/I(V).

Morphism of affine varieties

Using regular functions from an affine variety to A1, we can define regular maps from one affine variety to another. First we will define a regular map from a variety into affine space: Let V be a variety contained in An. Choose m regular functions on V, and call them f1, ..., fm. We define a regular map f from V to Am by letting f = (f1, ..., fm). In other words, each fi determines one coordinate of the range of f.

If V′ is a variety contained in Am, we say that f is a regular map from V to V′ if the range of f is contained in V′.

The definition of the regular maps apply also to algebraic sets. The regular maps are also called morphisms, as they make the collection of all affine algebraic sets into a category, where the objects are the affine algebraic sets and the morphisms are the regular maps. The affine varieties is a subcategory of the category of the algebraic sets.

Given a regular map g from V to V′ and a regular function f of k[V′], then f ∘ g ∈ k[V]. The map f → f ∘ g is a

Rational function and birational equivalence

In contrast to the preceding sections, this section concerns only varieties and not algebraic sets. On the other hand, the definitions extend naturally to projective varieties (next section), as an affine variety and its projective completion have the same field of functions.

If V is an affine variety, its coordinate ring is an integral domain and has thus a field of fractions which is denoted k(V) and called the field of the rational functions on V or, shortly, the function field of V. Its elements are the restrictions to V of the rational functions over the affine space containing V. The domain of a rational function f is not V but the complement of the subvariety (a hypersurface) where the denominator of f vanishes.

As with regular maps, one may define a rational map from a variety V to a variety V'. As with the regular maps, the rational maps from V to V' may be identified to the field homomorphisms from k(V') to k(V).

Two affine varieties are birationally equivalent if there are two rational functions between them which are

An affine variety is a rational variety if it is birationally equivalent to an affine space. This means that the variety admits a rational parameterization, that is a parametrization with rational functions. For example, the circle of equation is a rational curve, as it has the parametric equation

which may also be viewed as a rational map from the line to the circle.

The problem of resolution of singularities is to know if every algebraic variety is birationally equivalent to a variety whose projective completion is nonsingular (see also smooth completion). It was solved in the affirmative in characteristic 0 by Heisuke Hironaka in 1964 and is yet unsolved in finite characteristic.

Projective variety

Just as the formulas for the roots of second, third, and fourth degree polynomials suggest extending real numbers to the more algebraically complete setting of the complex numbers, many properties of algebraic varieties suggest extending affine space to a more geometrically complete projective space. Whereas the complex numbers are obtained by adding the number i, a root of the polynomial x2 + 1, projective space is obtained by adding in appropriate points "at infinity", points where parallel lines may meet.

To see how this might come about, consider the variety V(y − x2). If we draw it, we get a parabola. As x goes to positive infinity, the slope of the line from the origin to the point (x, x2) also goes to positive infinity. As x goes to negative infinity, the slope of the same line goes to negative infinity.

Compare this to the variety V(y − x3). This is a

The consideration of the projective completion of the two curves, which is their prolongation "at infinity" in the

Thus many of the properties of algebraic varieties, including birational equivalence and all the topological properties, depend on the behavior "at infinity" and so it is natural to study the varieties in projective space. Furthermore, the introduction of projective techniques made many theorems in algebraic geometry simpler and sharper: For example, Bézout's theorem on the number of intersection points between two varieties can be stated in its sharpest form only in projective space. For these reasons, projective space plays a fundamental role in algebraic geometry.

Nowadays, the projective space Pn of dimension n is usually defined as the set of the lines passing through a point, considered as the origin, in the affine space of dimension n + 1, or equivalently to the set of the vector lines in a vector space of dimension n + 1. When a coordinate system has been chosen in the space of dimension n + 1, all the points of a line have the same set of coordinates, up to the multiplication by an element of k. This defines the homogeneous coordinates of a point of Pn as a sequence of n + 1 elements of the base field k, defined up to the multiplication by a nonzero element of k (the same for the whole sequence).

A polynomial in n + 1 variables vanishes at all points of a line passing through the origin if and only if it is

The only regular functions which may be defined properly on a projective variety are the constant functions. Thus this notion is not used in projective situations. On the other hand, the field of the rational functions or function field is a useful notion, which, similarly to the affine case, is defined as the set of the quotients of two homogeneous elements of the same degree in the homogeneous coordinate ring.

Real algebraic geometry

Real algebraic geometry is the study of real algebraic varieties.

The fact that the field of the real numbers is an ordered field cannot be ignored in such a study. For example, the curve of equation is a circle if , but has no real points if . Real algebraic geometry also investigates, more broadly, semi-algebraic sets, which are the solutions of systems of polynomial inequalities. For example, neither branch of the hyperbola of equation is a real algebraic variety. However, the branch in the first quadrant is a semi-algebraic set defined by and .

One open problem in real algebraic geometry is the following part of Hilbert's sixteenth problem: Decide which respective positions are possible for the ovals of a nonsingular plane curve of degree 8.

Computational algebraic geometry

One may date the origin of computational algebraic geometry to meeting EUROSAM'79 (International Symposium on Symbolic and Algebraic Manipulation) held at Marseille, France, in June 1979. At this meeting,

- Dennis S. Arnon showed that George E. Collins's Cylindrical algebraic decomposition (CAD) allows the computation of the topology of semi-algebraic sets,

- Bruno Buchberger presented Gröbner bases and his algorithm to compute them,

- Daniel Lazard presented a new algorithm for solving systems of homogeneous polynomial equations with a computational complexity which is essentially polynomial in the expected number of solutions and thus simply exponential in the number of the unknowns. This algorithm is strongly related with Macaulay's multivariate resultant.

Since then, most results in this area are related to one or several of these items either by using or improving one of these algorithms, or by finding algorithms whose complexity is simply exponential in the number of the variables.

A body of mathematical theory complementary to symbolic methods called

Gröbner basis

A Gröbner basis is a system of generators of a polynomial ideal whose computation allows the deduction of many properties of the affine algebraic variety defined by the ideal.

Given an ideal I defining an algebraic set V:

- V is empty (over an algebraically closed extension of the basis field), if and only if the Gröbner basis for any monomial ordering is reduced to {1}.

- By means of the of V from any Gröbner basis of I for a monomial ordering refining the total degree.

- If the dimension of V is 0, one may compute the points (finite in number) of V from any Gröbner basis of I (see Systems of polynomial equations).

- A Gröbner basis computation allows one to remove from V all irreducible components which are contained in a given hypersurface.

- A Gröbner basis computation allows one to compute the Zariski closure of the image of V by the projection on the k first coordinates, and the subset of the image where the projection is not proper.

- More generally Gröbner basis computations allow one to compute the Zariski closure of the image and the critical points of a rational function of V into another affine variety.

Gröbner basis computations do not allow one to compute directly the primary decomposition of I nor the prime ideals defining the irreducible components of V, but most algorithms for this involve Gröbner basis computation. The algorithms which are not based on Gröbner bases use regular chains but may need Gröbner bases in some exceptional situations.

Gröbner bases are deemed to be difficult to compute. In fact they may contain, in the worst case, polynomials whose degree is doubly exponential in the number of variables and a number of polynomials which is also doubly exponential. However, this is only a worst case complexity, and the complexity bound of Lazard's algorithm of 1979 may frequently apply.

Cylindrical algebraic decomposition (CAD)

CAD is an algorithm which was introduced in 1973 by G. Collins to implement with an acceptable complexity the Tarski–Seidenberg theorem on quantifier elimination over the real numbers.

This theorem concerns the formulas of the first-order logic whose atomic formulas are polynomial equalities or inequalities between polynomials with real coefficients. These formulas are thus the formulas which may be constructed from the atomic formulas by the logical operators and (∧), or (∨), not (¬), for all (∀) and exists (∃). Tarski's theorem asserts that, from such a formula, one may compute an equivalent formula without quantifier (∀, ∃).

The complexity of CAD is doubly exponential in the number of variables. This means that CAD allows, in theory, to solve every problem of real algebraic geometry which may be expressed by such a formula, that is almost every problem concerning explicitly given varieties and semi-algebraic sets.

While Gröbner basis computation has doubly exponential complexity only in rare cases, CAD has almost always this high complexity. This implies that, unless if most polynomials appearing in the input are linear, it may not solve problems with more than four variables.

Since 1973, most of the research on this subject is devoted either to improving CAD or finding alternative algorithms in special cases of general interest.

As an example of the state of art, there are efficient algorithms to find at least a point in every connected component of a semi-algebraic set, and thus to test if a semi-algebraic set is empty. On the other hand, CAD is yet, in practice, the best algorithm to count the number of connected components.

Asymptotic complexity vs. practical efficiency

The basic general algorithms of computational geometry have a double exponential worst case complexity. More precisely, if d is the maximal degree of the input polynomials and n the number of variables, their complexity is at most for some constant c, and, for some inputs, the complexity is at least for another constant c′.

During the last 20 years of the 20th century, various algorithms have been introduced to solve specific subproblems with a better complexity. Most of these algorithms have a complexity .[1]

Among these algorithms which solve a sub problem of the problems solved by Gröbner bases, one may cite testing if an affine variety is empty and solving nonhomogeneous polynomial systems which have a finite number of solutions. Such algorithms are rarely implemented because, on most entries Faugère's F4 and F5 algorithms have a better practical efficiency and probably a similar or better complexity (probably because the evaluation of the complexity of Gröbner basis algorithms on a particular class of entries is a difficult task which has been done only in a few special cases).

The main algorithms of real algebraic geometry which solve a problem solved by CAD are related to the topology of semi-algebraic sets. One may cite counting the number of connected components, testing if two points are in the same components or computing a

Abstract modern viewpoint

The modern approaches to algebraic geometry redefine and effectively extend the range of basic objects in various levels of generality to schemes,

Most remarkably, in the late 1950s,

Sometimes other algebraic sites replace the category of affine schemes. For example,

Another formal generalization is possible to universal algebraic geometry in which every variety of algebras has its own algebraic geometry. The term variety of algebras should not be confused with algebraic variety.

The language of schemes, stacks and generalizations has proved to be a valuable way of dealing with geometric concepts and became cornerstones of modern algebraic geometry.

Algebraic stacks can be further generalized and for many practical questions like deformation theory and intersection theory, this is often the most natural approach. One can extend the

History

Before the 16th century

Some of the roots of algebraic geometry date back to the work of the

Renaissance

Such techniques of applying geometrical constructions to algebraic problems were also adopted by a number of

During the same period, Blaise Pascal and

19th and early 20th century

It took the simultaneous 19th century developments of

The second early 19th century development, that of Abelian integrals, would lead Bernhard Riemann to the development of Riemann surfaces.

In the same period began the algebraization of the algebraic geometry through

20th century

In the 1950s and 1960s,

An important class of varieties, not easily understood directly from their defining equations, are the abelian varieties, which are the projective varieties whose points form an abelian group. The prototypical examples are the elliptic curves, which have a rich theory. They were instrumental in the proof of Fermat's Last Theorem and are also used in elliptic-curve cryptography.

In parallel with the abstract trend of the algebraic geometry, which is concerned with general statements about varieties, methods for effective computation with concretely-given varieties have also been developed, which lead to the new area of computational algebraic geometry. One of the founding methods of this area is the theory of Gröbner bases, introduced by Bruno Buchberger in 1965. Another founding method, more specially devoted to real algebraic geometry, is the cylindrical algebraic decomposition, introduced by George E. Collins in 1973.

See also: derived algebraic geometry.

Analytic geometry

An

Modern analytic geometry is essentially equivalent to real and complex algebraic geometry, as has been shown by

Applications

Algebraic geometry now finds applications in

See also

- Glossary of classical algebraic geometry

- Important publications in algebraic geometry

- List of algebraic surfaces

- Noncommutative algebraic geometry

Notes

- Van der Waerden removed the chapter on elimination theory from the third edition (and all the subsequent ones) of his treatise Moderne algebra (in German).[citation needed]

References

- ^ "Complexity of Algorithms". www.cs.sfu.ca. Retrieved 2022-07-12.

- ^ Wikidata Q55886951.

- ^ Kline 1972, p. 108, 90.

- ISSN 0315-0860.

- ^ "Apollonius - Biography". Maths History. Retrieved 2022-11-11.

- S2CID 4059946.

- ISSN 0008-8994.

- ^ Kline 1972, p. 193.

- ^ Kline 1972, p. 193–195.

- ^ O'Connor, J. J.; Robertson, E. F. "Omar Khayyam". School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of St Andrews. Archived from the original on November 12, 2017.

Khayyam himself seems to have been the first to conceive a general theory of cubic equations.

- ^ Rashed, Roshdi (1994). The Development Of Arabic Mathematics Between Arithmetic And Algebra. Springer. pp. 102–103.

- ^ Oaks, Jeffrey (January 2016). "Excavating the errors in the "Mathematics" chapter of 1001 Inventions". Pp. 151-171 in: Sonja Brentjes, Taner Edis, Lutz Richter-Bernburd Edd., 1001 Distortions: How (Not) to Narrate History of Science, Medicine, and Technology in Non-Western Cultures. Archived from the original on 2021-02-27.

- ^ Kline 1972, p. 279.

- ISBN 978-3-7643-8904-8.

- ISBN 978-0-8176-4113-9.

- ISBN 9783540105657.

- ISBN 978-0-387-20874-9.

- ISBN 978-0-8218-7520-9.

- ^ Cipra, Barry Arthur (2007). "Algebraic Geometers See Ideal Approach to Biology" (PDF). SIAM News. 40 (6). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016.

- ISBN 978-3-540-72185-7.

- ISBN 978-0-8218-2127-5.

- JSTOR 2951732.

- arXiv:math-ph/0311005.

- ISBN 978-0-7190-1491-8.

- ISBN 978-0-8218-6758-7.

Sources

- Kline, M. (1972). Mathematical Thought from Ancient to Modern Times. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195061357.

Further reading

- Some classic textbooks that predate schemes

- van der Waerden, B. L. (1945). Einfuehrung in die algebraische Geometrie. Dover.

- Zbl 0796.14001.

- Zbl 0796.14002.

- Zbl 0796.14003.

- Modern textbooks that do not use the language of schemes

- Garrity, Thomas; et al. (2013). Algebraic Geometry A Problem Solving Approach. ISBN 978-0-821-89396-8.

- Zbl 0836.14001.

- Zbl 0779.14001.

- Zbl 0821.14001.

- Zbl 0701.14001.

- Zbl 0797.14001.

- Textbooks in computational algebraic geometry

- Zbl 0861.13012.

- Schenck, Hal (2003). Computational Algebraic Geometry. Cambridge University Press.

- Basu, Saugata; Pollack, Richard; Roy, Marie-Françoise (2006). Algorithms in real algebraic geometry. Springer-Verlag.

- González-Vega, Laureano; Recio, Tómas (1996). Algorithms in algebraic geometry and applications. Birkhaüser.

- Elkadi, Mohamed; Mourrain, Bernard; Piene, Ragni, eds. (2006). Algebraic geometry and geometric modeling. Springer-Verlag.

- LCCN 2007938208.

- Cox, David A.; Little, John B.; O'Shea, Donal (1998). Using algebraic geometry. Springer-Verlag.

- Caviness, Bob F.; Johnson, Jeremy R. (1998). Quantifier elimination and cylindrical algebraic decomposition. Springer-Verlag.

- Textbooks and references for schemes

- Zbl 0960.14002.

- Zbl 0118.36206.

- Zbl 0203.23301.

- Zbl 0367.14001.

- Zbl 0945.14001.

- Zbl 0797.14002.

External links

- Foundations of Algebraic Geometry by Ravi Vakil, 808 pp.

- Algebraic geometry entry on PlanetMath

- English translation of the van der Waerden textbook

- Dieudonné, Jean (March 3, 1972). "The History of Algebraic Geometry". Talk at the Department of Mathematics of the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee. Archived from the original on 2021-11-22 – via YouTube.

- The Stacks Project, an open source textbook and reference work on algebraic stacks and algebraic geometry