Alpine race

The Alpine race is a historical race concept defined by some late 19th-century and early 20th-century anthropologists as one of the sub-races of the Caucasian race.[1][2][3] The origin of the Alpine race was variously identified. Ripley argued that it migrated from Central Asia during the Neolithic Revolution, splitting the Nordic and Mediterranean populations. It was also identified as descending from the Celts residing in Central Europe in Neolithic times.[4] The Alpine race is supposedly distinguished by its moderate stature, neotenous features[dubious ], and cranial measurements, such as high cephalic index.[5]

History

The term "Alpine" (H. Alpinus) has historically been given to denote a physical type within the

The German

Adolf Hitler utilized the term Alpine to refer to a type of the Aryan race, and in an interview spoke admiringly about his idol Italian Fascist leader Benito Mussolini, commending Mussolini's Alpine racial heritage saying:

They know that Benito Mussolini is constructing a colossal empire which will put the Roman Empire in the shade. We shall put up [...] for his victories. Mussolini is a typical representative of our Alpine race

— Adolf Hitler, 1931[11]

It however fell out of popularity by the 1950s, but reappeared in the literature of

Physical appearance

A typical Alpine skull is regarded as

The Alpine race is short-headed and broad-faced. The cephalic index is about 88 on the average, the facial index under 83. In the Alpine race the length of the head is only a little or barely greater than the breadth, owing to the relatively considerable measurement of this latter. The Alpine head may be called round. It juts out only slightly over the nape, and this back part is fairly roomy, so that in the Alpine man only a little of the neck is to be seen above the coat-collar. The cast of countenance gives the effect of dullness, owing to the steeply rising forehead, vaulted backwards, the rather low bridge to the nose, the short, rather flat nose, set clumsily over the upper lip, the unprominent, broad, rounded chin.[16]

-

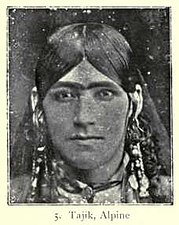

Tajikas an example of the Alpine type

-

An Italian from the Piedmont - of the Alpine (Alpinoid) type

-

An Austrian from the South Tyrol of the Alpine type

-

Meyers Blitz-Lexikon (Leipzig, 1932) shows the German cartographer Heinrich Kiepert as an example of the Alpine type

-

A Frenchman from theAuvergne- of the Alpine (Alpinoid) type

Ripley (1899) further notes that the nose of the Alpine is broader (mesorrhine) while their hair is usually a chestnut colour and their

Geography and origin

According to Ripley and Coon, the Alpine race is predominant in Central Europe and parts of Western/Central Asia. Ripley argued that the Alpines had originated in Asia, and had spread westwards along with the emergence and expansion of agriculture, which they established in Europe. By migrating into Central Europe, they had separated the northern and southern branches of the earlier European stock, creating the conditions for the separate evolution of Nordics and Mediterraneans. This model was repeated in Madison Grant's book The Passing of the Great Race (1916), in which the Alpines were portrayed as the most populous of European and western Asian races.[citation needed]

In

Alpine: A reduced and somewhat foetalized survivor of the Upper Palaeolithic population in Late Pleistocene France, highly brachycephalized; seems to represent in a large measure the bearer of the brachycephalic factor in Crô-Magnon. Close approximations to this type appear also in the Balkans and in the highlands of western and central Asia, suggesting that its ancestral prototype was widespread in Late Pleistocene times. In modern races it sometimes appears in a relatively pure form, sometimes as an element in mixed brachycephalic populations of multiple origin. It may have served in both Pleistocene and modern times as a bearer of the tendency toward brachycephalization into various population.

A debate concerning the origin of the Alpine race in Europe, involving Arthur Keith, John Myres and Alfred Cort Haddon was published by the Royal Geographical Society in 1906.[20]

The 1935 work of Frederick Orton states that the Alpine race was of

See also

References

- ^ ISBN 978-1-84519-415-4.

- ISBN 0-7591-0795-5.

- ^ The Races of Europe by Carleton S. Coon

- ISBN 0-486-42765-X.

- ^ Coon, Carleton (1939). The Races of Europe. Macmillan. pp. 437-438 Plate 11.

- JSTOR 2843096.

- JSTOR 2842946.

- S2CID 143811447.

- ^ "The Great Soviet Encyclopaedia" (in Russian).[unreliable source?]

- Hans F.K. Günther. Chapter IX Part Three: The Denordizationof the Peoples of Romance Speech: "The French Revolution was a very thorough denordization of France. At that time it was often enough to be blond to be dragged to the scaffold. The French Revolution must be read as an Alpine-Mediterranean rising against a noble and burgher upper class of Nordic race. The Alpine race has spread very fast, one might say astoundingly fast, in France in the nineteenth century."

- OCLC 906949733.

- OCLC 490400.

- ISBN 0-89874-510-1.

- ISBN 0-88133-482-0.

- ^ The Alpine Races in Europe, John L. Myres, The Geographical Journal, Vol. 28, No. 6 (Dec., 1906), pp. 537-553.

- ^ Günther, Hans (1927). The Racial Elements of European History. Kennikat Press. pp. 35-36.

- ^ The Races of Man. Differentiation and Dispersal of Man, p. 32.

- ^ Grant, Madison, The Passing of the Great Race, 1916, part 2, ch. 11; part 2, chapter 5.

- ^ Stevens Coon Carleton. (1939). "Chapter VIII. Introduction to the Study of the Living". The Races Of Europe. Osmania University, Digital Library Of India. The Macmillan Company. p. 291.

- ^ "The Alpine Races in Europe: Discussion, D. G. Hogarth, Arthur Evans, Dr. Haddon, Dr. Shrubsall, Mr. Hudleston, Mr. Gray, Dr. Wright and Mr. Myres", The Geographical Journal, Vol. 28, No. 6 (Dec., 1906) (pp. 553-560).

- ^ Orton, Sir Ernest Frederick (1935). Links with Past Ages. W. Heffer & Sons, Limited. p. 122.

Further reading

- Spiro, Jonathan P. (2009). Defending the Master Race: Conservation, Eugenics, and the Legacy of Madison Grant. Univ. of Vermont Press. ISBN 978-1-58465-715-6.