Alvin Hansen

Alvin Hansen | |

|---|---|

Secular stagnation theory |

| Part of a series on |

| Macroeconomics |

|---|

|

Alvin Harvey Hansen (August 23, 1887 – June 6, 1975) was an American economist who taught at the

More effectively than anyone else, he explicated, extended, domesticated, and popularized the ideas embodied in Keynes's The General Theory. He helped develop with John Hicks the IS–LM model (or Hicks–Hansen model), a mathematical representation of Keynesian macroeconomic theory. In 1967, Paul McCracken, chairman of the President's Council of Economic Advisers, saluted Hansen stating: "It is certainly a statement of fact that you have influenced the nation's thinking about economic policy more profoundly than any other economist in this century."[1]

Early life and education

Hansen was born in

Academic career

He taught at

In 1937 he received an invitation to occupy the new Lucius N. Littauer Chair of political Economy at

Later, his America's Role in the World Economy (1945) and Economic Policy and Full Employment (1947) made this case to a wider public. Hansen was appointment as special economic adviser to Marriner Eccles at the Federal Reserve Board in 1940 and he was in charge until 1945.

After retiring from active teaching in 1956, he wrote The American Economy (1957), Economic Issues of the 1960s and Problems (1964), and The Dollar and the International Monetary System (1965). He died in Alexandria, Virginia on June 6 of 1975 at the age of 87 years.[4]

Theories

His most outstanding contribution to economic theory was the joint development, with John Hicks, of the so-called IS–LM model, also known as the "Hicks–Hansen synthesis." The IS–LM diagram claims to show the relationship between the investment-saving (IS) curve and the liquidity preference-money supply (LM) curve. It is used in mainstream economics literature and textbooks to illustrate how monetary and fiscal policy can influence GDP.

Hansen's book of 1938, Full Recovery or Stagnation. based in Keynes's General Theory, presents his thesis for both growth and employment being stagnant if there is no economic state intervention to stimulate demand.

Hansen presented evidence on several occasions before the

Lately, theories of economic stagnation have become more associated with Hansen's ideas than with those of Keynes.[5]

Keynesianism

Hansen, in his review of The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, was skeptical of John Maynard Keynes's propositions, but by December 1938, in his presidential address to the American Economic Association, he embraced Keynesian theories of the need for government intervention in periods of economic recession. Soon after his arrival at Harvard in 1937, Hansen's famous graduate seminar on fiscal policy began inspiring graduate students such as Paul Samuelson and James Tobin (both of whom would go on to win the Economics Nobel) to further develop and popularize Keynesian economics. Hansen's 1941 book, Fiscal Policy and Business Cycles, was the first major work in the United States to entirely support Keynes's analysis of the causes of the Great Depression. Hansen used that analysis to argue for Keynesian deficit spending.

Hansen's best known contribution to economics was his and John Hicks's development of the IS–LM model, also known as the "Hicks–Hansen synthesis." The framework claims to graphically represent the investment-savings (IS) curve and the liquidity-money supply (LM) curve as an illustration of how fiscal and monetary policies can be employed to alter national income.

Hansen's 1938 book, Full Recovery or Stagnation, was based on Keynesian ideas and was an extended argument that there would be long-term employment stagnation without government demand-side intervention.

Paul Samuelson was Hansen's most famous student. Samuelson credited Hansen's Full Recovery or Stagnation? (1938) as the main inspiration for his famous multiplier-accelerator model of 1939. Leeson (1997) shows that while Hansen and Sumner Slichter continued to be regarded as leading exponents of Keynesian economics, their gradual abandonment of a commitment to price stability contributed to the development of a Keynesianism that conflicted with positions of Keynes himself.

Stagnation

In the late 1930s, Hansen argued that "secular stagnation" had set in so the American economy would never grow rapidly again because all the growth ingredients had played out, including technological innovation and population growth. The only solution, he argued, was constant, large-scale deficit spending by the federal government.

The thesis was highly controversial, as critics, such as George Terborgh, attacked Hansen as a "pessimist" and a "defeatist." Hansen replied that secular stagnation was just another name for Keynes's underemployment equilibrium. However, the sustained economic growth, beginning in 1940, undercut Hansen's predictions and his stagnation model was forgotten.[6][7]

Economic cycles

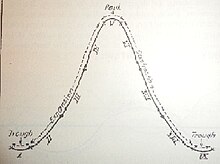

One of the most important contribution to the economic theory by Alvin Hansen are the economic cycles. In his book Business Cycles and National Income, he defines the cycle as a fluctuation in: employment, output, and prices. The cycle is divided in two phases: expansion, extending from trough to peak; and contraction, extending from peak to trough.

For Hansen, there exist stable and unstable economic cycles. The instability is caused by displacement due to external shocks. Hansen claims that the business-cycle analysis must take into consideration technical progress, the money market, and expectations.[8]

Public policy

Hansen argued that the American economy during the Great Depression was not going through a particularly severe business cycle but through the exhaustion of a longer-term progressive dynamic. What Hansen had in mind was not just counter-cyclical public spending to stabilize employment but rather major projects such as rural electrification, slum clearance, and natural resource development conservation, all with a view of opening up new investment opportunities for the private sector and so, restoring the economic dynamism needed to the system as a whole.[4]

Hansen trained and arguably influenced numerous students, many of whom later held government posts, and he served on numerous governmental committees dealing with economic issues. The American Economic Association awarded him its Walker Medal in 1967.[9]

Hansen frequently testified before Congress. He advocated against using unemployment to control inflation. He argued that inflation could be managed by timely changes in tax rates and the money supply, and by effective wage and price controls. He also advocated fiscal and other stimuli to ward off the stagnation that he thought was endemic to mature, industrialized economies. Hansen was not without his critics, however; journalist John T. Flynn, for example, argued that Hansen's policies were de facto fascism, sharing alarming similarities with the economic policy of Benito Mussolini, the dictator of Italy.[10]

During the

Between 1939 and 1945, he served as co-rapporteur to the economic and financial group of the Council on Foreign Relations's War and Peace Studies project, along with Chicago economist Jacob Viner.[11]

Hansen's advocacy (with Luther Gulick) during World War II of Keynesian policies to promote post-war full employment helped persuade Keynes to assist in the development of plans for the international economy.[12]

References

- ^ Miller (2002) p. 604

- ^ View/Search Fellows of the ASA Archived 2016-06-16 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 2016-07-23.

- SSRN 2173443

- ^ a b American National Biography, New York: Oxford UP, 1999

- ^ Hansen, Alvin H. Monetary Theory and Fiscal Policy, New York: McGraw-Hill, 1949

- ^ Benjamin Higgins, "Concepts and Criteria of Secular Stagnation," in Lloyd Metzler, ed. Income, employment and public policy: essays in honor of Alvin H. Hansen (Norton, 1964), pp 82+

- ^ Benjamin Higgins, "The Theory of Increasing Under-Employment," Economic Journal Vol. 60, No. 238 (Jun., 1950), pp. 255–274 in JSTOR

- ^ Hansen, Alvin H. Business Cycles and National Income, London: Allen and Unwin, 1964

- ^ Walker Medalists, American Economic Association

- ^ Flynn, John T. (1944). As We Go Marching (Doubleday & Co, Inc), see Part III: The Good Fascism: America

- ISBN 1-57181-003-X.

The rapporteurs of the Economic and Financial Group

- ^ Donald Markwell, John Maynard Keynes and International Relations: Economic Paths to War and Peace, Oxford University Press, 2006.

Primary sources

- Hansen, Alvin H. (1939). "Economic Progress and Declining Population Growth," American Economic Review (29) March. at JSTOR

- Hansen, Alvin H. (1941). Fiscal Policy and Business Cycles

- Hansen, Alvin H. (1949). Monetary Theory and Fiscal Policy. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Hansen, Alvin H. (1953). A Guide To Keynes, including the Preface. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Hansen, Alvin H. (1964). Business Cycles and National Income. London: AllenUnin.

Secondary sources

- Barber, William J. "The Career of Alvin H. Hansen in the 1920s and 1930s: a Study in Intellectual Transformation." History of Political Economy 1987 19(2): 191–205. ISSN 0018-2702

- Leeson, Robert. "The Eclipse of the Goal of Zero Inflation." History of Political Economy 1997 29(3): 445–496. ISSN 0018-2702Fulltext: in Ebsco. deals with Hansen and Sumner Slichter

- Donald Markwell, John Maynard Keynes and International Relations: Economic Paths to War and Peace, Oxford University Press (2006).

- Miller, John E. "From South Dakota Farm to Harvard Seminar: Alvin H. Hansen, America's Prophet of Keynesianism" Historian (2002) 64(3–4): 603–622. ISSN 0018-2370

- Rosenof, Theodore. Economics in the Long Run: New Deal Theorists and Their Legacies, 1933–1993 (1997)

- Seligman, Ben B., Main Currents in Modern Economics, 1962.

- American National Biography. New York: Oxford UP, 1999. Print.

Special issues of journals

- Quarterly Journal of Economics vol 90 # 1 (1976) pp. 1–37, online at JSTOR and/or in most college libraries.

- "Alvin Hansen on Economic Progress and Declining Population Growth" in Population and Development Review, Vol. 30, 2004