Amanita muscaria

| Amanita muscaria | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Division: | Basidiomycota |

| Class: | Agaricomycetes |

| Order: | Agaricales |

| Family: | Amanitaceae |

| Genus: | Amanita |

| Species: | A. muscaria

|

| Binomial name | |

| Amanita muscaria | |

| Subspecies and varieties | |

| |

| Amanita muscaria mycorrhizal | |

|---|---|

| Edibility is poisonous or psychoactive | |

Amanita muscaria, commonly known as the fly agaric or fly amanita,, white-spotted, and usually red mushroom.

Despite its easily distinguishable features, A. muscaria is a fungus with several known variations, or subspecies. These subspecies are slightly different, some having yellow or white caps, but are all usually called fly agarics, most often recognizable by their notable white spots. Recent DNA fungi research, however, has shown that some mushrooms called 'fly agaric' are in fact unique species, such as A. persicina (the peach-colored fly agaric).

Native throughout the

Although

Arguably the most iconic

Taxonomy

The name of the

The 16th-century Flemish botanist

The English mycologist John Ramsbottom reported that Amanita muscaria was used for getting rid of bugs in England and Sweden, and bug agaric was an old alternative name for the species.[12] French mycologist Pierre Bulliard reported having tried without success to replicate its fly-killing properties in his work Histoire des plantes vénéneuses et suspectes de la France (1784), and proposed a new binomial name Agaricus pseudo-aurantiacus because of this.[18] One compound isolated from the fungus is 1,3-diolein (1,3-di(cis-9-octadecenoyl)glycerol), which attracts insects.[19] It has been hypothesised that the flies intentionally seek out the fly agaric for its intoxicating properties.[20] An alternative derivation proposes that the term fly- refers not to insects as such but rather the delirium resulting from consumption of the fungus. This is based on the medieval belief that flies could enter a person's head and cause mental illness.[21] Several regional names appear to be linked with this connotation, meaning the "mad" or "fool's" version of the highly regarded edible mushroom Amanita caesarea. Hence there is oriol foll "mad oriol" in Catalan, mujolo folo from Toulouse, concourlo fouolo from the Aveyron department in Southern France, ovolo matto from Trentino in Italy. A local dialect name in Fribourg in Switzerland is tsapi de diablhou, which translates as "Devil's hat".[22]

Classification

Amanita muscaria is the

Description

A large, conspicuous mushroom, Amanita muscaria is generally common and numerous where it grows, and is often found in groups with basidiocarps in all stages of development. Fly agaric fruiting bodies emerge from the soil looking like white eggs. After emerging from the ground, the cap is covered with numerous small white to yellow pyramid-shaped warts. These are remnants of the universal veil, a membrane that encloses the entire mushroom when it is still very young. Dissecting the mushroom at this stage reveals a characteristic yellowish layer of skin under the veil, which helps identification. As the fungus grows, the red colour appears through the broken veil and the warts become less prominent; they do not change in size, but are reduced relative to the expanding skin area. The cap changes from globose to hemispherical, and finally to plate-like and flat in mature specimens.[28] Fully grown, the bright red cap is usually around 8–20 centimetres (3–8 inches) in diameter, although larger specimens have been found. The red colour may fade after rain and in older mushrooms.

The free gills are white, as is the spore print. The oval spores measure 9–13 by 6.5–9 μm; they do not turn blue with the application of iodine.[29] The stipe is white, 5–20 cm (2–8 in) high by 1–2 cm (1⁄2–1 in) wide, and has the slightly brittle, fibrous texture typical of many large mushrooms. At the base is a bulb that bears universal veil remnants in the form of two to four distinct rings or ruffs. Between the basal universal veil remnants and gills are remnants of the partial veil (which covers the gills during development) in the form of a white ring. It can be quite wide and flaccid with age. There is generally no associated smell other than a mild earthiness.[30][31]

Although very distinctive in appearance, the fly agaric has been mistaken for other yellow to red mushroom species in the Americas, such as

Controversy

Amanita muscaria varies considerably in its morphology, and many authorities recognize several subspecies or varieties within the species. In The Agaricales in Modern Taxonomy, German mycologist Rolf Singer listed three subspecies, though without description: A. muscaria ssp. muscaria, A. muscaria ssp. americana, and A. muscaria ssp. flavivolvata.[23]

However, a 2006 molecular phylogenetic study of different regional populations of A. muscaria by mycologist József Geml and colleagues found three distinct

Amanitaceae.org lists four varieties as of May 2019[update], but says that they will be segregated into their own taxa "in the near future". They are:[2]

| Image | Reference name | Common name | Synonym | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Amanita muscaria var. muscaria[1] | Euro-Asian fly agaric | Bright red fly agaric from northern Europe and Asia. Cap might be orange or yellow due to slow development of the purple pigment. Wide cap with white or yellow warts which are removed by rain.

Known to be toxic but used by shamans in northern cultures. Associated predominantly with Birch and diverse conifers in forest. | |

|

Amanita muscaria subsp. flavivolvata[3] | American fly agaric | red, with yellow to yellowish-white warts. It is found from southern Alaska down through the Rocky Mountains, through Central America, all the way to Andean Colombia. Rodham Tulloss uses this name to describe all "typical" A. muscaria from indigenous New World populations. | |

|

Amanita muscaria var. guessowii[4] | American fly agaric (yellow variant) | Amanita muscaria var. formosa | has a yellow to orange cap, with the centre more orange or perhaps even reddish orange. It is found most commonly in northeastern North America, from Newfoundland and Quebec south all the way to the state of Tennessee. Some authorities (cf. Jenkins) treat these populations as A. muscaria var. formosa, while others (cf. Tulloss) recognise them as a distinct variety. |

|

Amanita muscaria var. inzengae[42] | Inzenga's fly agaric | it has a pale yellow to orange-yellow cap with yellowish warts and stem which may be tan. |

Distribution and habitat

A. muscaria is a

Toxicity

A. muscaria poisoning has occurred in young children and in people who ingested the mushrooms for a

or who confused it with an edible species.A. muscaria contains several biologically active agents, at least one of which,

Deaths from A. muscaria have been reported in historical journal articles and newspaper reports,[58][59][60] but with modern medical treatment, fatal poisoning from ingesting this mushroom is extremely rare.[61] Many books list A. muscaria as deadly,[62] but according to David Arora, this is an error that implies the mushroom is far more toxic than it is.[63] Furthermore, The North American Mycological Association has stated that there were "no reliably documented cases of death from toxins in these mushrooms in the past 100 years".[64]

The active constituents of this species are water-soluble, and boiling and then discarding the cooking water at least partly detoxifies A. muscaria.[65] Drying may increase potency, as the process facilitates the conversion of ibotenic acid to the more potent muscimol.[66] According to some sources, once detoxified, the mushroom becomes edible.[67][68] Patrick Harding describes the Sami custom of processing the fly agaric through reindeer.[69]

Pharmacology

Muscarine, discovered in 1869,[70] was long thought to be the active hallucinogenic agent in A. muscaria. Muscarine binds with muscarinic acetylcholine receptors leading to the excitation of neurons bearing these receptors. The levels of muscarine in Amanita muscaria are minute when compared with other poisonous fungi[71] such as Inosperma erubescens, the small white Clitocybe species C. dealbata and C. rivulosa. The level of muscarine in A. muscaria is too low to play a role in the symptoms of poisoning.[72]

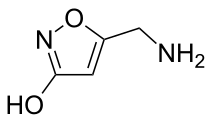

The major toxins involved in A. muscaria poisoning are

Ibotenic acid and muscimol are structurally related to each other and to two major

Symptoms

Fly agarics are best known for the unpredictability of their effects. Depending on habitat and the amount ingested per body weight, effects can range from mild

In cases of serious poisoning the mushroom causes

Treatment

Medical attention should be sought in cases of suspected poisoning. If the delay between ingestion and treatment is less than four hours,

There is no antidote, and supportive care is the mainstay of further treatment for intoxication. Though sometimes referred to as a

Uses

Psychoactive

The wide range of psychoactive effects have been variously described as depressant, sedative-hypnotic, psychedelic, dissociative, or deliriant; paradoxical effects such as stimulation may occur however. Perceptual phenomena such as synesthesia, macropsia, and micropsia may occur; the latter two effects may occur either simultaneously or alternatingly, as part of Alice in Wonderland syndrome, collectively known as dysmetropsia, along with related distortions pelopsia and teleopsia. Some users report lucid dreaming under the influence of its hypnotic effects. Unlike Psilocybe cubensis, A. muscaria cannot be commercially cultivated, due to its mycorrhizal relationship with the roots of pine trees. However, following the outlawing of psilocybin mushrooms in the United Kingdom in 2006, the sale of the still legal A. muscaria began increasing.[90]

Siberia

A. muscaria was widely used as an

The

Other reports and theories

The Finnish historian

"The story of Santa emerging from a Sámi shamanic tradition has a critical number of flaws," asserts Tim Frandy, assistant professor of Nordic Studies at the University of British Columbia and a member of the Sámi descendent community in North America. "The theory has been widely criticized by Sámi people as a stereotypical and problematic romanticized misreading of actual Sámi culture."[106]

Vikings

The notion that

Soma

In 1968,

Christianity

Philologist, archaeologist, and

Fly trap

Amanita muscaria is traditionally used for catching flies possibly due to its content of ibotenic acid and muscimol, which lead to its common name "fly agaric". Recently, an analysis of nine different methods for preparing A. muscaria for catching flies in Slovenia have shown that the release of ibotenic acid and muscimol did not depend on the solvent (milk or water) and that thermal and mechanical processing led to faster extraction of ibotenic acid and muscimol.[123]

Culinary

The toxins in A. muscaria are water-soluble: parboiling A. muscaria fruit bodies can detoxify them and render them edible,

Use of this mushroom as a food source also seems to have existed in North America. A classic description of this use of A. muscaria by an

A 2008 paper by food historian William Rubel and mycologist David Arora gives a history of consumption of A. muscaria as a food and describes detoxification methods. They advocate that Amanita muscaria be described in field guides as an edible mushroom, though accompanied by a description on how to detoxify it. The authors state that the widespread descriptions in field guides of this mushroom as poisonous is a reflection of

In culture

An account of the journeys of Philip von Strahlenberg to Siberia and his descriptions of the use of the mukhomor there was published in English in 1736. The drinking of urine of those who had consumed the mushroom was commented on by Anglo-Irish writer Oliver Goldsmith in his widely read 1762 novel, Citizen of the World.[135] The mushroom had been identified as the fly agaric by this time.[136] Other authors recorded the distortions of the size of perceived objects while intoxicated by the fungus, including naturalist Mordecai Cubitt Cooke in his books The Seven Sisters of Sleep and A Plain and Easy Account of British Fungi.[137] This observation is thought to have formed the basis of the effects of eating the mushroom in the 1865 popular story Alice's Adventures in Wonderland.[138] A hallucinogenic "scarlet toadstool" from Lappland is featured as a plot element in Charles Kingsley's 1866 novel Hereward the Wake based on the medieval figure of the same name.[139] Thomas Pynchon's 1973 novel Gravity's Rainbow describes the fungus as a "relative of the poisonous Destroying angel" and presents a detailed description of a character preparing a cookie bake mixture from harvested Amanita muscaria.[140] Fly agaric shamanism is also explored in the 2003 novel Thursbitch by Alan Garner.[141]

See also

References

- ^ a b c Tulloss RE; Yang Z-L (2012). "Amanita muscaria Singer". Studies in the Genus Amanita Pers. (Agaricales, Fungi). Retrieved 2019-05-06.

- ^ a b c "Infraspecific taxa of muscaria". amanitaceae.org.

- ^ a b c Tulloss RE; Yang Z-L (2012). "Amanita muscaria subsp. flavivolvata Singer". Studies in the Genus Amanita Pers. (Agaricales, Fungi). Retrieved 2013-02-21.

- ^ a b c Tulloss RE; Yang Z-L (2012). "Amanita muscaria var. guessowii Veselý". Studies in the Genus Amanita Pers. (Agaricales, Fungi). Retrieved 2013-02-21.

- ^ "Standardized Common Names for Wild Species in Canada". National General Status Working Group. 2020.

- ^ doi:10.29203/ka.1992.294. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2018-05-15. Retrieved 2018-05-15.

- .

- PMID 16203016.

- ^ Biderman, Chris (2023-10-14). "They look delightful but California hospital warns against eating these poisonous mushrooms". Health & Medicine. Sacramento Bee. Sacramento, California, U.S. Retrieved 2024-02-23.

- ^ Wasson, Soma, p. 198.

- ^ Magnus A. (1256). "Book II, Chapter 6; p. 87 and Book VI, Chapter 7; p. 345". De vegetabilibus.

- ^ a b Ramsbottom, p. 44.

- ^ Clusius C. (1601). "Genus XII of the pernicious mushrooms". Rariorum plantarum historia.

- ^ Linnaeus C. (1745). Flora svecica [suecica] exhibens plantas per regnum Sueciae crescentes systematice cum differentiis specierum, synonymis autorum, nominibus incolarum, solo locorum, usu pharmacopæorum (in Latin). Stockholm: Laurentii Salvii.

- ^ Linnaeus C (1753). "Tomus II". Species Plantarum (in Latin). Vol. 2. Stockholm: Laurentii Salvii. p. 1172.

- ISBN 978-0-304-52257-6.

- ISBN 978-3-540-66493-2.

- ^ Wasson, Soma, p. 200.

- ^ a b Benjamin, Mushrooms: poisons and panaceas, pp. 306–07.

- ISBN 978-0-89281-986-7.

- ^ S2CID 41451034.

- ^ Wasson, Soma, p. 194

- ^ ISBN 978-3-87429-254-2.

- ISBN 978-0-916422-55-4.

- ^ Tulloss RE; Yang Z-L (2012). "Amanita sect. Amanita". Studies in the Genus Amanita Pers. (Agaricales, Fungi). Retrieved 2013-02-21.

- PMID 10877939. Archived from the original(PDF) on 6 March 2009. Retrieved 2009-02-16.

- JSTOR 3761246. Archived from the originalon 2008-12-28. Retrieved 2009-02-16.

- ISBN 978-0-584-10324-3.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-89815-169-5.

- ISBN 978-0-8317-3080-2.

- ISBN 978-0-330-44237-4.

- ^ S2CID 21075349.

- ISBN 978-0-222-79414-7.

- ISBN 978-0-486-21861-8.

- ISBN 978-0-646-44674-5.

- ^ Benjamin, Mushrooms: poisons and panaceas, pp. 303–04.

- ^ S2CID 10246338. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2011-07-16.

- S2CID 619242. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2009-03-26. Retrieved 2009-10-28.

- ^ Tulloss, R. E. (2012). "Amanita breckonii Ammirati & Thiers". Studies in the Genus Amanita Pers. (Agaricales, Fungi) – Tulloss RE, Yang Z-L. Retrieved 2013-02-21.

- ^ Tulloss, R. E. (2012). "Amanita gioiosa S. Curreli ex S. Curreli". Studies in the Genus Amanita Pers. (Agaricales, Fungi) – Tulloss RE, Yang Z-L. Retrieved 2013-02-21.

- ^ Tulloss, R. E. (2012). "Amanita heterochroma S. Curreli". Studies in the Genus Amanita Pers. (Agaricales, Fungi) – Tulloss RE, Yang Z-L. Retrieved 2013-02-21.

- ^ "Amanita muscaria var. inzengae - Amanitaceae.org - Taxonomy and Morphology of Amanita and Limacella". www.amanitaceae.org.

- ^ Benjamin, Mushrooms: poisons and panaceas, p. 305.

- S2CID 89306634.

- S2CID 85352273.

- .

- ^ ISBN 978-1-876473-51-8.

- ISBN 978-0-478-10835-4.

- ^ May T. (2006). "News from the Fungimap president". Fungimap Newsletter. 29: 1.

- ^ Robinson R (2010). "First Record of Amanita muscaria in Western Australia" (PDF). Australasian Mycologist. 29 (1): 4–6.

- ISBN 978-0-643-06523-9.

- ^ PMID 1347320.

- ^ S2CID 115828300.

- PMID 5696006.

- ^ a b c d e Chilton WS (1975). "The course of an intentional poisoning". MacIlvanea. 2: 17.

- ^ PMID 15904689.

- ^ Cagliari GE (1897). "Mushroom poisoning". Medical Record. 52: 298.

- ^ PMID 14016551.

- ^ "Vecchi's death said to be due to a deliberate experiment with poisonous mushrooms" (PDF). The New York Times. 19 December 1897. Retrieved 2009-02-02.

- ^ PMID 9173659.

- ISBN 978-1-55407-651-2.

- ^ Arora, Mushrooms demystified, p. 894.

- ^ "Mushroom poisoning syndromes". North American Mycological Association (NAMA) website. NAMA. Archived from the original on 4 April 2009. Retrieved 2009-03-22.

- ^ a b c d Piqueras, J. (10 January 1990). "Amanita muscaria, Amanita pantherina and others". IPCS INTOX Databank. Retrieved 2008-12-08.

- ^ Benjamin, Mushrooms: poisons and panaceas, p. 310.

- ^ S2CID 19585416. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2020-11-12. Retrieved 2011-02-09.

- ^ Shaw, Hank (2011-12-24). "How to Safely Eat Amanita Muscaia". honest-food.net. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04.

- YouTube

- OCLC 6699630.

- S2CID 9153757.

- ^ Benjamin, Mushrooms: poisons and panaceas, p. 306.

- ^ S2CID 4178793.

- ^ PMID 5891631.

- PMID 14291871.

- PMID 14266560.

- ^ Lampe, K.F., 1978. "Pharmacology and therapy of mushroom intoxications". In: Rumack, B.H., Salzman, E. (Eds.), Mushroom Poisoning: Diagnosis and Treatment. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, pp. 125–169

- .

- PMID 17376693.

- .

- ^ PMID 10885458.

- PMID 15833352.

- ISBN 978-0-914728-15-3.

- S2CID 29957973.

- S2CID 218865551.

- ISBN 978-0-7817-2845-4.

- ISBN 978-0-8151-4387-1.

- ^ Benjamin, Mushrooms: poisons and panaceas, p. 313.

- PMID 5892794.

- ISBN 978-92-9168-249-2. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2012-03-29. Retrieved 2009-02-13.

- ISBN 978-0-07-068443-0.

- ^ Wasson, Soma, p. 161.

- ISBN 978-0-02-328764-0.

- ^ Ramsbottom, p. 45.

- ^ Wasson, Soma, pp. 234–35.

- S2CID 13693096.

- ^ Wasson, Soma, p. 279.

- ^ Mochtar, S. G.; Geerken, H. (1979). "The Hallucinogens Muscarine and Ibotenic Acid in the Middle Hindu Kush: A contribution on traditional medicinal mycology in Afghanistan". Afghanistan Journal (in German). 6. Translated by P. G. Werner: 62–65. Archived from the original on 17 February 2009. Retrieved 2009-02-23.

Several Shutulis asserted that Amanita-extract was administered orally as a medicine for treatment of psychotic conditions, as well as externally as a therapy for localised frostbite.

- ISBN 978-1-879528-18-5.

- .

- ^ Letcher, p. 149.

- ISBN 978-0-89281-672-9.

- ^ Xulu, Melanie (2017-12-12). "Santa Claus the Magic Mushroom & the Psychedelic Origins of Christmas". MOOF. Retrieved 2020-12-26.

- ^ "Magic mushrooms & Reindeer - Weird Nature - BBC animals - YouTube". www.youtube.com. Archived from the original on 2021-12-11. Retrieved 2020-12-26.

- ^ a b Kevin Feeney (2020). "Fly Agaric: A Compendium of History, Pharmacology, Mythology, & Exploration". ResearchGate. Retrieved 2020-12-26.

- ^ a b Campbell, Olivia (Dec 21, 2023). "What does Santa have to do with … psychedelic mushrooms?". National Geographic. Retrieved 2023-12-22.

- ^ (in Swedish) Ödmann S. (1784) Försök at utur Naturens Historia förklara de nordiska gamla Kämpars Berserka-gang (An attempt to Explain the Berserk-raging of Ancient Nordic Warriors through Natural History). Kongliga Vetenskaps Academiens nya Handlingar 5: 240–247 (In: Wasson, 1968)

- ^ ISBN 978-0-12-351850-7.

- S2CID 199548329.

- ^ Wasson, Soma, p. 10.

- ^ Letcher, p. 145.

- ^ Wasson, Soma, p. 18.

- ^ Wasson, Soma, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Wasson, Soma, pp. 22–24.

- ^ Letcher, p. 146.

- S2CID 84458441.

- ISBN 978-0-88316-517-1.

- ISBN 978-0-520-09627-1.

- ^

Allegro, J. (1970). The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross: A Study of the Nature and Origins of Roman Theology within the Fertility Cults of the Ancient Near East. London: Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 978-0-340-12875-6.

- ^ Letcher, p. 160.

- ISBN 978-0-340-12597-7.

- ^ Letcher, p. 161.

- PMID 27063872.

- ^ Viess, Debbie. "Further Reflections on Amanita muscaria as an Edible Species"

- ^ Coville, F. V. 1898. Observations on Recent Cases of Mushroom Poisoning in the District of Columbia. United States Department of Agriculture, Division of Botany. U.S. Government Printing office, Washington, D.C.

- ^ Phipps, A. G.; Bennett, B.C.; Downum, K. R. (2000). Japanese use of Beni-tengu-dake (Amanita muscaria) and the efficacy of traditional detoxification methods (Thesis). Florida International University, Miami, Florida.

- ^ "Art Registry: 1750–1850". Mykoweb. Archived from the original on 2 February 2009. Retrieved 2009-02-26.

- ^ Benjamin, Mushrooms: poisons and panaceas, p. 295.

- ^ "The Registry of Mushrooms in Works of Art". Mykoweb. Archived from the original on 1 February 2009. Retrieved 2009-02-16.

- PMID 12747324.

- ^ "Mushrooms in Victorian Fairy Paintings, by Elio Schachter". Mushroom, the Journal of Wild Mushrooming. Archived from the original on 15 January 2009. Retrieved 2009-02-16.

- ^ "The Top 11 Video Game Powerups". UGO Networks. Archived from the original on October 28, 2008.

- PMID 16203016.

- ^ Ramsbottom, p. 43.

- ^ Letcher, p. 122.

- ^ Letcher, p. 123.

- ^ Letcher, p. 125.

- ^ Letcher, p. 126.

- ^ Letcher, p. 127.

- ISBN 978-0-09-953321-4.

- ^ Letcher, p. 129.

Works cited

- ISBN 978-0-9825562-7-6.

- ISBN 978-0-89815-169-5.

- Benjamin, Denis R. (1995). Mushrooms: poisons and panaceas—a handbook for naturalists, mycologists and physicians. New York: WH Freeman and Company. ISBN 978-0-7167-2600-5.

- Furst, Peter T. (1976). Hallucinogens and Culture. Chandler & Sharp. pp. 98–106. ISBN 978-0-88316-517-1.

- Letcher, Andy (2006). Shroom: A Cultural history of the magic mushroom. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-22770-9.

- Ramsbottom, J. (1953). Mushrooms & Toadstools. Collins. ISBN 978-1-870630-09-2.

- Wasson, R. Gordon (1968). Soma: Divine Mushroom of Immortality. Harcourt Brace Jovanovick. ISBN 978-0-88316-517-1.

External links

- Webpages on Amanita species by Tulloss and Yang Zhuliang

- Amanita on erowid.org

- Aminita muscaria, Amanita pantherina and others (Group PIM G026) by IPCS INCHEM