Amitriptyline

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌæmɪˈtrɪptɪliːn/[1] |

| Trade names | Elavil, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682388 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intramuscular injection |

| Drug class | Tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 45%[5]-53%[6] |

| Protein binding | 96%[7] |

| Metabolism | Liver (CYP2D6, CYP2C19, CYP3A4)[9][6][10] |

| Metabolites | nortriptyline, (E)-10-hydroxynortriptyline |

| Elimination half-life | 21 hours[5] |

| Excretion | Urine: 12–80% after 48 hours;[8] feces: not studied |

| Identifiers | |

| |

JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 197.5 °C (387.5 °F) [11] |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Amitriptyline, sold under the brand name Elavil among others, is a

The most common side effects are dry mouth, drowsiness, dizziness, constipation, and weight gain. Glaucoma, liver toxicity and abnormal heart rhythms are rare but serious side effects. Blood levels of amitriptyline vary significantly from one person to another,[17] and amitriptyline interacts with many other medications potentially aggravating its side effects.

Amitriptyline was discovered in the late 1950s by scientists at

Medical uses

Amitriptyline is

Depression

Amitriptyline is effective for depression,[23] but it is rarely used as a first-line antidepressant due to its higher toxicity in overdose and generally poorer tolerability.[24] It can be tried for depression as a second-line therapy, after the failure of other treatments.[13] For treatment-resistant adolescent depression[25] or for cancer-related depression[26] amitriptyline is no better than placebo, however the number of treated patients in both studies was small. It is sometimes used for the treatment of depression in Parkinson's disease,[27] but supporting evidence for that is lacking.[28]

Pain

Amitriptyline alleviates painful

Low doses of amitriptyline moderately improve sleep disturbances and reduce pain and fatigue associated with

There is some (low-quality) evidence that amitriptyline may reduce pain in cancer patients. It is recommended only as a second line therapy for non-chemotherapy-induced neuropathic or mixed neuropathic pain, if opioids did not provide the desired effect.[35]

Moderate evidence exists in favor of amitriptyline use for atypical facial pain.[36] Amitriptyline is ineffective for HIV-associated neuropathy.[29]

In multiple sclerosis it is frequently used to treat painful paresthesias in the arms and legs (e.g., burning sensations, pins and needles, stabbing pains) caused by damage to the pain regulating pathways of the brain and spinal cord.[37]

Headache

Amitriptyline is probably effective for the prevention of periodic migraine in adults. Amitriptyline is similar in efficancy to venlafaxine and topiramate but carries a higher burden of adverse effects than topiramate.[16] For many patients, even very small doses of amitriptyline are helpful, which may allow for minimization of side effects.[38] Amitriptyline is not significantly different from placebo when used for the prevention of migraine in children.[39]

Amitriptyline may reduce the frequency and duration of chronic

Other indications

Amitriptyline is effective for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome; however, because of its side effects, it should be reserved for select patients for whom other agents do not work.[41][42][43] There is insufficient evidence to support its use for abdominal pain in children with functional gastrointestinal disorders.[44]

Amitriptyline may improve pain and urgency intensity associated with

In the US, amitriptyline is commonly used in children with

Contraindications and precautions

The known contraindications of amitriptyline are:[12]

- History of myocardial infarction

- History of arrhythmias, particularly any degree of heart block

- Coronary artery disease

- Porphyria

- Severe liver disease (such as cirrhosis)

- Being under six years of age

- Patients who are taking monoamine oxidase inhibitors(MAOIs) or have taken them within the last 14 days

Amitriptyline should be used with caution in patients with epilepsy, impaired liver function, pheochromocytoma, urinary retention, prostate enlargement, hyperthyroidism, and pyloric stenosis.[12]

In patients with the rare condition of shallow anterior chamber of eyeball and narrow anterior chamber angle, amitriptyline may provoke attacks of acute glaucoma due to dilation of the pupil. It may aggravate psychosis, if used for depression with schizophrenia, or precipitate the switch to mania in those with bipolar disorder.[12]

CYP2D6 poor metabolizers should avoid amitriptyline due to increased side effects. If it is necessary to use it, half dose is recommended.[57] Amitriptyline can be used during pregnancy and lactation when SSRIs have been shown not to work.[58]

Side effects

The most frequent side effects, occurring in 20% or more of users, are dry mouth, drowsiness, dizziness, constipation, and weight gain (on average 1.8 kg

A less common side effect of amitriptyline is urination problems (8.7%).[23]

Amitriptyline can increase suicidal thoughts and behavior in people under the age of 24 and was black boxed by the FDA for these qualifiers due to this potential side effect.[60] Amitriptyline-associated sexual dysfunction (occurring at a frequency of 6.9%) seems to be mostly confined to males with depression and is expressed predominantly as erectile dysfunction and low libido disorder, with lesser frequency of ejaculatory and orgasmic problems. The rate of sexual dysfunction in males treated for indications other than depression and in females is not significantly different from placebo.[61]

Liver tests abnormalities occur in 10–12% of patients on amitriptyline, but are usually mild, asymptomatic and transient,[62] with consistently elevated alanine transaminase in 3% of all patients.[63][64] The increases of the enzymes above the 3-fold threshold of liver toxicity are uncommon, and cases of clinically apparent liver toxicity are rare;[62] nevertheless, amitriptyline is placed in the group of antidepressants with greater risks of hepatic toxicity.[63]

Amitriptyline

Overdose

The symptoms and the treatment of an overdose are largely the same as for the other TCAs, including the presentation of serotonin syndrome and adverse cardiac effects. The British National Formulary notes that amitriptyline can be particularly dangerous in overdose,[68] thus it and other TCAs are no longer recommended as first-line therapy for depression. The treatment of overdose is mostly supportive as no specific antidote for amitriptyline overdose is available. Activated charcoal may reduce absorption if given within 1–2 hours of ingestion. If the affected person is unconscious or has an impaired gag reflex, a nasogastric tube may be used to deliver the activated charcoal into the stomach. ECG monitoring for cardiac conduction abnormalities is essential and if one is found close monitoring of cardiac function is advised. Body temperature should be regulated with measures such as heating blankets if necessary. Cardiac monitoring is advised for at least five days after the overdose.

Interactions

Since amitriptyline and its active metabolite nortriptyline are primarily metabolized by cytochromes CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 (see Amitriptyline#Pharmacology), the inhibitors of these enzymes are expected to exhibit pharmacokinetic interactions with amitriptyline. According to the prescribing information, the interaction with CYP2D6 inhibitors may increase the plasma level of amitriptyline.[12] However, the results in the other literature are inconsistent:[9] the co-administration of amitriptyline with a potent CYP2D6 inhibitor paroxetine does increase the plasma levels of amitriptyline two-fold and of the main active metabolite nortriptyline 1.5-fold,[69] but combination with less potent CYP2D6 inhibitors thioridazine or levomepromazine does not affect the levels of amitriptyline and increases nortriptyline by about 1.5-fold;[70] a moderate CYP2D6 inhibitor fluoxetine does not seem to have a significant effect on the levels of amitriptyline or nortriptyline.[71][72] A case of clinically significant interaction with potent CYP2D6 inhibitor terbinafine has been reported.[73]

A potent inhibitor of

Oral contraceptives may increase the blood level of amitriptyline by as high as 90%.[76] Valproate moderately increases the levels of amitriptyline and nortriptyline through an unclear mechanism.[77]

The prescribing information warns that the combination of amitriptyline with monoamine oxidase inhibitors may cause potentially lethal serotonin syndrome;[12] however, this has been disputed.[78] The prescribing information cautions that some patients may experience a large increase in amitriptyline concentration in the presence of topiramate.[79] However, other literature states that there is little or no interaction: in a pharmacokinetic study topiramate only increased the level of amitriptyline by 20% and nortriptyline by 33%.[80]

Amitriptiline counteracts the antihypertensive action of

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

| Site | AMI | NTI | Species | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SERT | 2.8–36 | 15–279 | Human | [85][86] |

| NET | 19–102 | 1.8–21 | Human | [85][86] |

| DAT | 3,250 | 1,140 | Human | [85] |

| 5-HT1A | 450–1,800 | 294 | Human | [87][88] |

| 5-HT1B | 840 | ND | Rat | [89] |

| 5-HT2A | 18–23 | 41 | Human | [87][88] |

| 5-HT2B | 174 | ND | Human | [90] |

| 5-HT2C | 4-8 | 8.5 | Rat | [91][92] |

| 5-HT3 | 430 | 1,400 | Rat | [93] |

| 5-HT6 | 65–141 | 148 | Human/rat | [94][95][96] |

| 5-HT7 | 92.8–123 | ND | Rat | [97] |

| α1A | 6.5–25 | 18–37 | Human | [98][99] |

| α1B | 600–1700 | 850–1300 | Human | [98][99] |

| α1D | 560 | 1500 | Human | [99] |

| α2 | 114–690 | 2,030 | Human | [86][87] |

| α2A | 88 | ND | Human | [100] |

| α2B | >1000 | ND | Human | [100] |

| α2C | 120 | ND | Human | [100] |

β |

>10,000 | >10,000 | Rat | [101][92] |

D1 |

89 | 210 (rat) | Human/rat | [102][92] |

D2 |

196–1,460 | 2,570 | Human | [87][102] |

D3 |

206 | ND | Human | [102] |

D4 |

ND | ND | ND | ND |

D5 |

170 | ND | Human | [102] |

| H1 | 0.5–1.1 | 3.0–15 | Human | [102][103][104] |

| H2 | 66 | 646 | Human | [103] |

| H3 | 75,900;>1000 | 45,700 | Human | [102][103] |

| H4 | 34–26,300 | 6,920 | Human | [103][105] |

| M1 | 11.0–14.7 | 40 | Human | [106][107] |

| M2 | 11.8 | 110 | Human | [106] |

| M3 | 12.8–39 | 50 | Human | [106][107] |

| M4 | 7.2 | 84 | Human | [106] |

| M5 | 15.7–24 | 97 | Human | [106][107] |

| σ1 | 287–300 | 2,000 | Guinea pig/rat | [108][109] |

hERG |

3,260 | 31,600 | Human | [110][111] |

| PARP1 | 1650 | ND | Human | [112] |

TrkA |

3,000 (agonist) |

ND | Human | [113] |

TrkB |

14,000 (agonist) |

ND | Human | [113] |

| Values are Ki (nM), unless otherwise noted. The smaller the value, the more strongly the drug binds to the site. | ||||

Amitriptyline inhibits serotonin transporter (SERT) and norepinephrine transporter (NET). It is metabolized to nortriptyline, a stronger norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, further augmenting amitriptyline's effects on norepinephrine reuptake (see table in this section).

Amitriptyline additionally acts as a potent inhibitor of the

Amitriptyline is a non-selective blocker of multiple ion channels, in particular,

Mechanism of action

Inhibition of serotonin and norepinephrine transporters by amitriptyline results in interference with neuronal reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine. Since the reuptake process is important physiologically in terminating transmitting activity, this action may potentiate or prolong activity of serotonergic and adrenergic neurons and is believed to underlie the antidepressant activity of amitriptyline.[79]

Inhibition of norepinephrine reuptake leading to increased concentration of norepinephrine in the

Pharmacokinetics

Amitriptyline is readily absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract (90–95%).[6] Absorption is gradual with the peak concentration in blood plasma reached after about 4 hours.[5] Extensive metabolism on the first pass through the liver leads to average bioavailability of about 50% (45%[5]-53%[6]). Amitriptyline is metabolized mostly by CYP2C19 into nortriptyline and by CYP2D6 leading to a variety of hydroxylated metabolites, with the principal one among them being (E)-10-hydroxynortriptyline[9] (see metabolism scheme),[6] and to a lesser degree, by CYP3A4.[10]

Nortriptyline, the main active metabolite of amitriptyline, is an antidepressant on its own right. Nortriptyline reaches 10% higher level in the blood plasma than the parent drug amitriptyline and 40% greater area under the curve, and its action is an important part of the overall action of amitriptyline.[5][9]

Another active metabolite is (E)-10-hydroxynortriptyline, which is a norepinephrine uptake inhibitor four times weaker than nortriptyline. (E)-10-hydroxynortiptyline blood level is comparable to that of nortriptyline, but its cerebrospinal fluid level, which is a close proxy of the brain concentration of a drug, is twice higher than nortriptyline's. Based on this, (E)-10-hydroxynortriptyline was suggested to significantly contribute to antidepressant effects of amitriptyline.[119]

Blood levels of amitriptyline and nortriptyline and pharmacokinetics of amitriptyline in general, with clearance difference of up to 10-fold, vary widely between individuals.[120] Variability of the area under the curve in steady state is also high, which makes a slow upward titration of the dose necessary.[17]

In the blood, amitriptyline is 96% bound to plasma proteins; nortriptyline is 93–95% bound, and (E)-10-hydroxynortiptyline is about 60% bound.[7][121][119] Amitriptyline has an elimination half life of 21 hours,[5] nortriptyline – 23–31 hours,[122] and (E)-10-hydroxynortiptyline - 8–10 hours.[119] Within 48 hours, 12-80% of amitriptyline is eliminated in the urine, mostly as metabolites.[8] 2% of the unchanged drug is excreted in the urine.[123] Elimination in the feces, apparently, have not been studied.

Therapeutic levels of amitriptyline range from 75 to 175 ng/mL (270–631 nM),[124] or 80–250 ng/mL of both amitriptyline and its metabolite nortriptyline.[125]

Pharmacogenetics

Since amitriptyline is primarily metabolized by CYP2D6 and CYP2C19, genetic variations within the genes coding for these enzymes can affect its metabolism, leading to changes in the concentrations of the drug in the body.[126] Increased concentrations of amitriptyline may increase the risk for side effects, including anticholinergic and nervous system adverse effects, while decreased concentrations may reduce the drug's efficacy.[127][128][129][130]

Individuals can be categorized into different types of CYP2D6 or CYP2C19 metabolizers depending on which genetic variations they carry. These metabolizer types include poor, intermediate, extensive, and ultrarapid metabolizers. Most individuals (about 77–92%) are extensive metabolizers,[57] and have "normal" metabolism of amitriptyline. Poor and intermediate metabolizers have reduced metabolism of the drug as compared to extensive metabolizers; patients with these metabolizer types may have an increased probability of experiencing side effects. Ultrarapid metabolizers use amitriptyline much faster than extensive metabolizers; patients with this metabolizer type may have a greater chance of experiencing pharmacological failure.[127][128][57][130]

The Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium recommends avoiding amitriptyline in patients who are CYP2D6 ultrarapid or poor metabolizers, due to the risk for a lack of efficacy and side effects, respectively. The consortium also recommends considering an alternative drug not metabolized by CYP2C19 in patients who are CYP2C19 ultrarapid metabolizers. A reduction in starting dose is recommended for patients who are CYP2D6 intermediate metabolizers and CYP2C19 poor metabolizers. If use of amitriptyline is warranted, therapeutic drug monitoring is recommended to guide dose adjustments.[57] The Dutch Pharmacogenetics Working Group also recommends selecting an alternative drug or monitoring plasma concentrations of amitriptyline in patients who are CYP2D6 poor or ultrarapid metabolizers, and selecting an alternative drug or reducing initial dose in patients who are CYP2D6 intermediate metabolizers.[131]

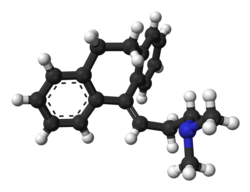

Chemistry

Amitriptyline is a highly lipophilic molecule having an

History

Amitriptyline was first developed by the American pharmaceutical company Merck in the late 1950s. In 1958, Merck approached a number of clinical investigators proposing to conduct clinical trials of amitriptyline for schizophrenia. One of these researchers, Frank Ayd, instead, suggested using amitriptyline for depression. Ayd treated 130 patients and, in 1960, reported that amitriptyline had antidepressant properties similar to another, and the only known at the time, tricyclic antidepressant imipramine.[135] Following this, the US Food and Drug Administration approved amitriptyline for depression in 1961.[18]

In Europe, due to a quirk of the patent law at the time allowing patents only on the chemical synthesis but not on the drug itself,

According to research by the historian of psychopharmacology David Healy, amitriptyline became a much bigger selling drug than its precursor imipramine because of two factors. First, amitriptyline has much stronger anxiolytic effect. Second, Merck conducted a marketing campaign raising clinicians' awareness of depression as a clinical entity.[136][135]

Society and culture

In the 2021 film The Many Saints of Newark, amitriptyline (referred to by the brand name Elavil) is part of the plot line of the movie.[137]

Names

Amitriptyline is the English and French

Prescription trends

Between 1998 and 2017, along with imipramine, amitriptyline was the most commonly prescribed first antidepressant for children aged 5–11 years in England. It was also the most prescribed antidepressant (along with fluoxetine) for 12 to 17-year olds.[142]

Research

The few randomized controlled trials investigating amitriptyline efficacy in eating disorder have been discouraging.[143]

See also

References

- ^ "Amitriptyline". Oxford Dictionary. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 6 January 2021 – via Lexico.com.

- ^ "Amitriptyline Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 2 September 2020. Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- FDA. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ Anvisa (31 March 2023). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 4 April 2023). Archived from the original on 3 August 2023. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ^ S2CID 41881790.

- ^ S2CID 231596860.

- ^ a b c d e "Endep Amitriptyline hydrochloride" (PDF). TGA eBusiness Services. Alphapharm Pty Limited. 10 December 2012. Archived from the original on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- ^ S2CID 20844722.

- ^ S2CID 25565048.

- ^ S2CID 27146286.

- ISBN 9780122608032.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Amitriptyline Tablets BP 50mg – Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC)". electronic Medicines Compendium. Actavis UK Ltd. 24 March 2013. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7020-5516-4.

- ^ S2CID 211074023.

- ^ PMID 27377815.

- ^ PMID 22529202.

- ^ S2CID 23560743.

- ^ S2CID 31018835.

- hdl:10665/345533. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2021.02.

- ^ "Amitriptyline Hydrochloride". Drugs.com. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 24 September 2014. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2021". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 15 January 2024. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ "Amitriptyline - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ PMID 23235671.

- ISBN 978-0-9805790-9-3.

- PMID 25433401.

- PMID 24950919.

- ^ "Parkinson's disease". merckmanuals.com. Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. August 2007. Archived from the original on 18 November 2013. Retrieved 22 December 2013.

- PMID 22021174.

- ^ PMID 33145709.

- S2CID 258013544.

- PMID 36007534.

- S2CID 24955042.

- ^ S2CID 195671256.

- PMID 29457627.

- S2CID 37418010.

- S2CID 222256076.

- ^ "Elavil for MS". nationalmssociety.org. Retrieved 7 July 2023.

- S2CID 52071815.

- PMID 31413170.

- PMID 26859719.

- PMID 24992947.

- ISSN 0140-6736.

- ^ "Irritable bowel syndrome: low-dose antidepressant improves symptoms". NIHR Evidence. 26 March 2024.

- PMID 33560523.

- PMID 31241819.

- S2CID 49674883.

- PMID 32904438.

- PMID 26789925.

- S2CID 58577978.

- PMID 24567616.

- PMID 29761479.

- S2CID 250536370.

- ^ Atkin T, Comai S, Gobbi G. Drugs for Insomnia beyond Benzodiazepines: Pharmacology, Clinical Applications, and Discovery. Pharmacol Rev. 2018 Apr;70(2):197-245. doi: 10.1124/pr.117.014381. PMID 29487083.

- ^ Pecknold JC, Luthe L. Trimipramine, anxiety, depression and sleep. Drugs. 1989;38 Suppl 1:25-31; discussion 49-50. doi: 10.2165/00003495-198900381-00007. PMID 2693052.

- ^ Riemann D, Voderholzer U, Cohrs S, Rodenbeck A, Hajak G, Rüther E, Wiegand MH, Laakmann G, Baghai T, Fischer W, Hoffmann M, Hohagen F, Mayer G, Berger M. Trimipramine in primary insomnia: results of a polysomnographic double-blind controlled study. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2002 Sep;35(5):165-74. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-34119. PMID 12237787.

- ^ Berger M, Gastpar M. Trimipramine: a challenge to current concepts on antidepressives. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1996;246(5):235-9. doi: 10.1007/BF02190274. PMID 8863001.

- ^ PMID 23486447.

- S2CID 11327135.

- PMID 25590213.

- ^ Thour A, Marwaha R (18 July 2023). "Amitriptyline". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved 18 March 2024.

- PMID 29019272.

- ^ from the original on 21 January 2022. Retrieved 6 January 2021 – via PubMed.

- ^ PMID 24362450.

- PMID 13961401.

- from the original on 21 December 2016.

- S2CID 3447931.

- PMID 32252558.

- ISBN 978-0-85711-084-8.

- S2CID 22476829.

- ^ S2CID 1428027.

- ^ PMID 8685072.

- PMID 1454161.

- PMID 16175144.

- S2CID 25430195.

- S2CID 25670895.

- PMID 27444984.

- S2CID 37720622.

- S2CID 12179122.

- ^ a b c "DailyMed – AMITRIPTYLINE HYDROCHLORIDE tablet, film coated". Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- S2CID 10427097.

- PMID 5468457.

- PMID 7092508.

- ^ "CHAPTER 132 ORAL ANTICOAGULATION | Free Medical Textbook". 9 February 2012. Archived from the original on 27 September 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ Roth BL, Driscol J. "PDSP Ki Database". Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the United States National Institute of Mental Health. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- ^ PMID 9537821.

- ^ PMID 9400006.

- ^ S2CID 21236268.

- ^ S2CID 41570165.

- S2CID 25108290.

- S2CID 19578349.

- S2CID 24889381.

- ^ S2CID 19490821.

- PMID 2533080.

- S2CID 35874409.

- S2CID 33743899.

- PMID 7680751.

- PMID 8394362.

- ^ S2CID 207225294.

- ^ PMID 32608144.

- ^ PMID 22982401.

- PMID 8699.

- ^ PMID 19091563.

- ^ S2CID 14274150.

- PMID 16782354.

- from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- ^ PMID 8100134.

- ^ S2CID 19891653.

- PMID 2877462.

- S2CID 38476281.

- ^ PMID 10742304.

- PMID 22244872.

- PMID 28442756.

- ^ PMID 19549602.

- S2CID 23385313.

- S2CID 4478321.

- PMID 10688618.

- from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 15 October 2009.

- S2CID 4929937.

- ^ S2CID 38046048.

- S2CID 22923577.

- ^ "Pamelor, Aventyl (nortriptyline) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 2 December 2013.

- PMID 7248140.

- ^ "Amitriptyline". drugbank.ca. Archived from the original on 30 January 2019. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- ISBN 978-0-7817-8746-8. Archivedfrom the original on 8 July 2017.

- PMID 2683251.

- S2CID 7940406.

- ^ S2CID 20888081.

- ^ PMID 17113714.

- from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 4 November 2018.

- ^ from the original on 26 October 2020. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- S2CID 2475005.

- ^ The Pharmaceutical Codex. 1994. Principles and practice of pharmaceutics, 12th edn. Pharmaceutical press

- ^ Hansch C, Leo A, Hoekman D. 1995. Exploring QSAR.Hydrophobic, electronic and steric constants. Washington, DC: American Chemical Society.

- PMID 16552741.

- ^ ISBN 0674039572.

- ^ ISBN 1860360106.

- ^ Press J (10 January 2021). "The Sopranos Fan's Guide to The Many Saints of Newark". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on 1 October 2021. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

Livia is already troubled enough in the yesteryear of Many Saints that her doctor wants to prescribe her the antidepressant Elavil, but she rejects it. "I'm not a drug addict!" she sneers. Tony pores over the Elavil pamphlet with great interest and even schemes with Dickie Moltisanti to get his suffering mother to take it: "It could make her happy."

- ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3. Archivedfrom the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1.

- ISBN 978-94-011-4439-1. Archivedfrom the original on 15 February 2017.

- ^ a b "Amitriptyline". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- PMID 32697803.

- PMID 21414249.

Further reading

- Dean L (March 2017). "Amitriptyline Therapy and CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 Genotype". In Pratt VM, McLeod HL, Rubinstein WS, Scott SA, Dean LC, Kattman BL, et al. (eds.). Medical Genetics Summaries. PMID 28520380.