Anarchism in Nigeria

| Part of a series on |

| Anarchism |

|---|

|

Anarchism in Nigeria has its roots in the organization of various stateless societies that inhabited pre-colonial Nigeria, particularly among the

History

With the exception of the north, which was largely dominated by the

The early Nigerian labor movement

The Nigerian labor movement began to constitute itself almost immediately after the introduction of British capitalism to the region. During the early 1900s, agitation increased in response to the imposition of employment contracts, which obliged work without any provisions for workers' rights.[8] Nigerian workers became conscious of the racial disparities opening up in Colonial Nigeria, with European workers earning more than Africans for the same work.[9] Conditions worsened during the Great Depression, as the colonial government imposed direct taxation on Nigerian workers and converted permanent employment into day labor.[10] The rumours that the Igbo women were being assessed for taxation sparked off the Women's War in Aba, a massive revolt organized and executed by women.[11][12] Inspired by the anti-colonial writings of Nnamdi Azikiwe, Nigerian workers became more radicalized throughout the 1930s, aiming to bring an end to British colonial rule through class conflict.[10]

The rise of

Independence and military rule

In 1960, the

After the military junta reneged on the

After the

The contemporary Nigerian anarchist movement

During this period of

During the

The struggle against the dictatorship reached an apex in 1994, when petroleum workers called a strike demanding the end of the military dictatorship. The Awareness League and other trade unions joined the strike, bringing economic life around Lagos and the southwest to a standstill. After calling off a threatened strike in July, the NLC reconsidered a general strike in August after the government imposed conditions on Abiola's release. On 17 August 1994, the government dismissed the leadership of the NLC and the petroleum unions, placed the unions under appointed administrators, and arrested Frank Kokori and other labor leaders. According to Sam Mbah, "never since the civil war of the 1960s had the Nigerian state come so close to disintegrating."[40]

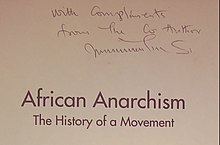

With the death of Sani Abacha in 1998, his successor initiated a transition back to democratic rule, establishing the Fourth Nigerian Republic. In the wake of democratization, many community groups and leftists organizations were now left without the common enemy of military rule, leading some - including the Awareness League - to begin fragmenting.[41] During this period, Sam Mbah and I.E. Igariwey published their book African Anarchism, which compiles a history of the anarchist movement in Africa and draws from the anarchic traditional practices of many of Nigeria' indigenous peoples.

During the End SARS protests of 2020, which called for the abolition of the Special Anti-Robbery Squad, protestors set fire to police stations, government buildings and banks, while also releasing prisoners.[42] President Muhammadu Buhari reacted to the movement by warning young Nigerians of anarchists that were allegedly attempting to hijack the protests[43] and stated that the federal government "would not tolerate anarchy in the country".[44]

References

- ^ Mbah & Igariwey 1997, p. 35.

- ^ Mbah & Igariwey 1997, pp. 35–36.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-521-48061-1.

- ISBN 978-1-57607-682-8.

- ISBN 978-0-521-48061-1.

- ISBN 978-1-57958-245-6.

- ISBN 978-978-134-400-8.

- OCLC 923243778.

- OCLC 186831169.

- ^ OCLC 462715003.

- OCLC 1158882885.

- OCLC 265134.

- JSTOR 41971222.

- OCLC 462715003.

- OCLC 462195042.

- OCLC 930445576.

- ^ Mbah & Igariwey 1997, pp. 58–59.

- ^ Mbah & Igariwey 1997, pp. 47–48.

- ^ Abubakar Ibrahim (July 29, 2008). "The Forgotten Interim President". Daily Trust. Retrieved February 28, 2010.

- ISBN 9780875867090.

- JSTOR 3518821.

- ^ "Civil War". countrystudies.us. Federal Research Division of the Library of Congress. 1991. Retrieved November 21, 2019.

- Halbrook, Stephen P. (1972). "Anarchism and Revolution in Black Africa". The Journal of Contemporary Revolutions. IV (1). Archived from the originalon March 7, 2005.

- ^ Schmidt, Michael (September 9, 2008). "Nostalgic Tribalism or Revolutionary Transformation?". Zabalaza (9). Zabalaza Anarchist Communist Front: 26.

- ^ ATOFARATI, ABUBAKAR .A. "The Nigerian Civil War: Causes, Strategies, And Lessons Learnt". Global Security. Retrieved November 16, 2016.

- ^ Mbah & Igariwey 1997, p. 86.

- ^ a b Mbah & Igariwey 1997, p. 88.

- OCLC 44229291.

- ^ Mbah & Igariwey 1997, pp. 52, 68.

- ^ Mbah & Igariwey 1997, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Schmidt, Michael (September 9, 2008). "Nostalgic Tribalism or Revolutionary Transformation?". Zabalaza (9). Zabalaza Anarchist Communist Front: 29.

- ^ Mbah & Igariwey 1997, p. 70.

- Workers' Solidarity Alliance.

- JSTOR 723365.

- ^ News from Africa Watch (August 27, 1993). "Nigeria, Democracy Derailed: Hundreds Arrested and Press Muzzled in Aftermath of Election Annulment". Human Rights Watch. 5 (11): 1–21.

- S2CID 146316411.

- ^ Ogbeidi, Michael M. (2010). "A Culture of Failed Elections: Revisiting Democratic Elections in Nigeria, 1959-2003". Historia Actual Online. 21: 43–56.

- .

- Workers Solidarity Movement. 1993.

- ^ Mbah & Igariwey 1997, p. 61.

- ^ Jeremy; Mbah, Sam (March 2012). "Interview with Sam Mbah: Towards an Anarchist Spring in Nigeria". Sydney: Jura Books Collective. Retrieved October 15, 2015.

- ^ "Prison Breaks and Torched Police Stations in #EndSARS Uprising in Nigeria". Abolition Media Worldwide. October 23, 2020. Retrieved April 12, 2021.

- ^ Nseyen, Nsikak (October 19, 2020). "End SARS: Beware of anarchists who may hijack protest – Buhari tells protesters". Daily Post. Retrieved April 12, 2021.

- ^ Akinola, Wale (October 19, 2020). "EndSARS protests have been hijacked to destabilise Buhari's govt, says Lai Mohammed". Legit.ng. Retrieved April 12, 2021.

Bibliography

- OCLC 614189872.

External links

- Nigeria section - The Anarchist Library

- Nigeria section - Libcom.org