Propaganda of the deed

This article possibly contains original research. Verify whether incidents in "notable actions" are known as propaganda of the deed. (June 2018) |

| Part of a series on |

| Anarchism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Libertarianism |

|---|

Propaganda of the deed (or propaganda by the deed, from the French propagande par le fait[1]) is specific political direct action meant to be exemplary to others and serve as a catalyst for revolution.

It is primarily associated with acts of violence perpetrated by proponents of

Anarchist origins

Various definitions

One of the first individuals to conceptualise propaganda by the deed was the Italian revolutionary Carlo Pisacane (1818–1857), who wrote in his "Political Testament" (1857) that "ideas spring from deeds and not the other way around."[5] Mikhail Bakunin (1814–1876), in his "Letters to a Frenchman on the Present Crisis" (1870) stated that "we must spread our principles, not with words but with deeds, for this is the most popular, the most potent, and the most irresistible form of propaganda."[6]

Some anarchists, such as

Beverly Gage, professor of U.S. history at Yale University, elaborates on what the concept meant to outsiders and those within the anarchist movement:

To outsiders, the talk of bombing and assassination that suddenly pulsed through revolutionary circles in the late 1870s sounded like little more than an indiscriminate call to violence. To Most and others within the anarchist movement, by contrast, the idea of propaganda by deed, or the attentat (attack), had a very specific logic. Among anarchism's founding premises was the idea that capitalist society was a place of constant violence: every law, every church, every paycheck was based on force. In such a world, to do nothing, to stand idly by while millions suffered, was itself to commit an act of violence. The question was not whether violence per se might be justified, but exactly how violence might be maximally effective for, in Most's words, annihilating the "beast of property" that "makes mankind miserable, and gains in cruelty and voracity with the progress of our so called civilization."[12]

By the 1880s, the slogan "propaganda of the deed" had begun to be used both within and outside of the anarchist movement to refer to individual bombings, regicides and tyrannicides. In 1881, "propaganda by the deed" was formally adopted as a strategy by the anarchist London Congress.[3]

As early as 1887, a few important figures in the anarchist movement had begun to distance themselves from individual acts of violence. Peter Kropotkin thus wrote that year in Le Révolté that "a structure based on centuries of history cannot be destroyed with a few kilos of dynamite".[13] A variety of anarchists advocated the abandonment of these sorts of tactics in favor of collective revolutionary action, for example through the trade union movement. The anarcho-syndicalist, Fernand Pelloutier, argued in 1895 for renewed anarchist involvement in the labor movement on the basis that anarchism could do very well without "the individual dynamiter."[14]

Later anarchist authors advocating "propaganda of the deed" included the German anarchist Gustav Landauer, and the Italians Errico Malatesta and Luigi Galleani. For Gustav Landauer, "propaganda of the deed" meant the creation of libertarian social forms and communities that would inspire others to transform society.[16]

At the other extreme, the anarchist Luigi Galleani, perhaps the most vocal proponent of "propaganda by the deed" from the turn of the century through the end of the First World War, took undisguised pride in describing himself as a subversive, a revolutionary propagandist and advocate of the violent overthrow of established government and institutions through the use of 'direct action', i.e., bombings and assassinations.

Relationship to revolution

Propaganda of the deed thus included stealing (in particular bank robberies – named "expropriations" or "revolutionary expropriations" to finance the organization), rioting and general strikes which aimed at creating the conditions of an insurrection or even a revolution. These acts were justified as the necessary counterpart to state repression. As early as 1911, Leon Trotsky condemned individual acts of violence by anarchists as useful for little more than providing an excuse for state repression. "The anarchist prophets of the 'propaganda by the deed' can argue all they want about the elevating and stimulating influence of terrorist acts on the masses," he wrote in 1911, "Theoretical considerations and political experience prove otherwise." Vladimir Lenin largely agreed, viewing individual anarchist acts of terrorism as an ineffective substitute for coordinated action by disciplined cadres of the masses. Both Lenin and Trotsky acknowledged the necessity of violent rebellion and assassination to serve as a catalyst for revolution, but they distinguished between the ad hoc bombings and assassinations carried out by proponents of the propaganda of the deed, and organized violence coordinated by a professional revolutionary vanguard utilized for that specific end.[21]

Notable actions

This timeline lists some significant actions that have been described as "Propaganda of the deed" since the 19th century.

- 17 February 1880 – Stepan Khalturin successfully blows up part of the Winter Palace in an attempt to assassinate Tsar Alexander II of Russia. Although the Tsar escapes unharmed, eight soldiers are killed and 45 wounded. Referring to the 1862 invention of dynamite, historian Benedict Anderson observes that "Nobel's invention had now arrived politically."[23] Khalturin is hanged on the orders of Alexander's son and successor, Alexander III, in 1882 after the assassination of a police official.

- 13 March [Narodnaya Volya.[24]

- 23 July 1892 – Homestead Strike, resulting in the deaths of seven striking members of the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers. Although badly wounded, Frick survives, and Berkman is arrested and eventually sentenced to 22 years in prison.[22]

- 7 November 1893 – The Spanish anarchist Santiago Salvador throws two Guillaume Tell, killing some twenty people and injuring scores of others.[25]

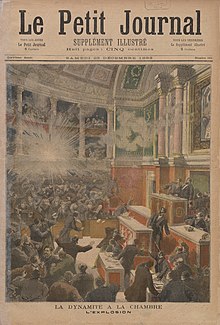

- 9 December 1893 – French National Assembly, killing nobody and injuring one. He is then sentenced to death and executed by the guillotine on 4 February 1894, shouting "Death to bourgeois society and long live anarchy!" (A mort la société bourgeoise et vive l'anarchie!). During his trial, Vaillant declares that he had not intended to kill anybody, but only to injure several deputies in retaliation against the execution of Ravachol, who was executed for four bombings.[4]

- 12 February 1894 – Émile Henry, intending to avenge Auguste Vaillant, sets off a bomb in Café Terminus (a café near the Gare Saint-Lazare train station in Paris), killing one and injuring twenty. During his trial, when asked why he wanted to harm so many innocent people, he declares, "There is no innocent bourgeois." This act is one of the rare exceptions to the rule that propaganda of the deed targets only specific powerful individuals. Henry is convicted and executed by guillotine on 21 May.[4]

- 15 February 1894 – A chemical explosive carried by Martial Bourdin prematurely detonates outside the Royal Observatory, Greenwich in Greenwich Park, killing him.[26]

- 24 June 1894 – Italian anarchist Sadi Carnot, the President of France, to death. Caserio is executed by guillotine on 15 August.[4]

- 8 August 1897 – garotte on 20 August.[27]

- 10 September 1898 – Luigi Lucheni stabs to death Empress Elisabeth, the consort of Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria-Hungary, with a needle file in Geneva, Switzerland. Lucheni is sentenced to life in prison and eventually commits suicide in his cell.[28]

- 29 July 1900 – Gaetano Bresci shoots dead King Umberto, in revenge for the Bava Beccaris massacre in Milan. Due to the abolition of capital punishment in Italy, Bresci is sentenced to penal servitude for life on Santo Stefano Island, where he is found dead less than a year later.[30]

- 6 September 1901 – Leon Czolgosz shoots U.S. President William McKinley at point-blank range at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York. McKinley dies on 14 September, and Czolgosz is executed by electric chair on 29 October. Czolgosz's anarchist views have been debated.[29]

- 15 November 1902 – Requiem Mass for his recently deceased wife, Queen Marie Henriette. All three of Rubino's shots miss the monarch's carriage, and he is quickly subdued by the crowd and taken into police custody. He is sentenced to life imprisonment and dies in prison in 1918.[31]

- 21 July 1905 – Members of the attempt on the life of Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II, but the bomb missed its target, instead killing 26 people and wounded 58 others. One of the conspirators, the Armenian anarchist Christapor Mikaelian, was killed during the planning stages. The Belgian anarchist Edward Joris was also among those arrested and convicted for their part in the plot.[32]

- 31 May 1906 – Catalan anarchist Alfonso XIII of Spain and Queen Victoria Eugenie immediately after their wedding by throwing a bomb into the procession. The King and Queen are unhurt, but 24 bystanders and horses are killed and over 100 persons injured. Morral is apprehended two days later and commits suicide while being transferred to prison.[33]

- 1 February 1908 – Luis Filipe, respectively, in the Lisbon Regicide. Both Buiça and Costa, who are sympathetic to a republican movement in Portugal that includes anarchist elements, are shot dead by police officers.[34]

- 15 June 1910 – The Bosnian anarchist Bogdan Žerajić attempts to assassinate the Governor of Bosnia and Herzegovian Marijan Varešanin, but failed and subsequently committed suicide.[35]

- 14 September 1911 –

- 12 November 1912 – Anarchist Manuel Pardiñas shoots Spanish Prime Minister José Canalejas dead in front of a Madrid bookstore. Pardiñas then immediately turns the gun on himself and commits suicide.[24]

- 9 February 1913 – The farmers Mulatilo Virgilio, Fermin Perez and Fabian Graciano assassinate Salvadoran President Manuel Enrique Araujo with machetes.[36]

- 18 March 1913 – Alexandros Schinas shoots dead King George I of Greece while the monarch is on a walk near the White Tower of Thessaloniki. Schinas is captured and tortured; he commits suicide on 6 May by jumping out the window of the gendarmerie, although there is speculation that he could have been thrown to his death.[37]

- 4 July 1914 – A bomb being prepared for use at John D. Rockefeller's home at Tarrytown, New York explodes prematurely, killing three anarchists, Arthur Caron, Carl Hansen and Charles Berg,[38] and an innocent woman, Mary Chavez[39]

- 13 October and 14 November 1914 – Galleanists – radical followers of Luigi Galleani – explode two bombs in New York City after police forcibly disperse a protest by anarchists and communists at John D. Rockefeller's home in Tarrytown.[38]

- 16 September 1920 – The Wall Street bombing kills 38 and wounds 400 in the Manhattan Financial District. Galleanists are believed responsible, particularly Mario Buda, the group's principal bombmaker, although the crime remains officially unsolved.[40]

- 31 October 1926 – fascist squads).[41][verification needed]

- 27 September 1932 – A dynamite-filled package bomb left by Galleanists destroys Judge Webster Thayer's home in Worcester, Massachusetts, injuring his wife and a housekeeper.[42][43] Judge Thayer had presided over the trials of Galleanists Sacco and Vanzetti.[44]

See also

References

- S2CID 159570078. Retrieved 28 May 2021.

- ^ Anarchist historian George Woodcock, when dealing with the evolution of anarcho-pacifism in the early 20th century, reports that "the modern pacifist anarchists, ...have tended to concentrate their attention largely on the creation of libertarian communities – particularly farming communities – within present society, as a kind of peaceful version of the propaganda by deed." George Woodcock. Anarchism: A History of Libertarian Ideas and Movements (1962), page 20.

- ^ ISBN 978-0300217926 – via Google Books.

- ^ ISBN 978-1629631127.

- ^ ISBN 978-0765619884.

- ^ Bakunin, Mikhail (1870). Letter to a Frenchman on the Present Crisis – via Marxists Internet Archive.

- ^ "Action as Propaganda". dwardmac.pitzer.edu.

- ISBN 978-0199759286 – via Google Books.

- ^ Ketcham, Christopher (16 December 2014). "When Revolution Came to America". Vice. Retrieved 8 April 2017.

- ISBN 978-0199759286 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Chapter 4". dwardmac.pitzer.edu.

- ISBN 978-0199759286 – via Google Books.

- ^ quoted in Billington, James H. 1998. Fire in the minds of men: origins of the revolutionary faith New Jersey: Transaction Books, p. 417.

- Black Rose Books. Archived from the originalon 29 September 2008. Retrieved 26 October 2010.

- post-war Germany, the prohibition of the Communist Party (KPD) and thus of institutional far-left political organization may also, in the same manner, have played a role in the creation of the Red Army Faction.

- Black Rose Books. Archived from the originalon 29 September 2008. Retrieved 18 April 2006.

- ^ Galleani, Luigi, La Fine Dell'Anarchismo?, ed. Curata da Vecchi Lettori di Cronaca Sovversiva, University of Michigan (1925), pp. 61–62: Galleani's writings are clear on this point: he had undisguised contempt for those who refused to both advocate and directly participate in the violent overthrow of capitalism.

- ^ a b Galleani, Luigi, Faccia a Faccia col Nemico, Boston, MA: Gruppo Autonomo, (1914)

- ^ a b Avrich, Paul, Sacco and Vanzetti: The Anarchist Background, Princeton University Press (1991), pp. 51, 98–99

- ^ Avrich, Paul, Anarchist Voices: An Oral History of Anarchism in America, Princeton: Princeton University Press (1996), p. 132 (Interview of Charles Poggi)

- ISBN 978-0199759286 – via Google Books.

- ^ ISBN 978-0199759286.

- ^ Anderson, Benedict (July–August 2004). "In the World-Shadow of Bismarck and Nobel". New Left Review. II (28). New Left Review.

- ^ ISBN 978-1441166869.

- ^ ISBN 978-0745640389.

- ^ "Propaganda by Deed - the Greenwich Observatory Bomb of 1894". Archived from the original on 17 February 2013.

- ^ ISBN 978-0520063983.

- ^ ISBN 978-1610692854.

- ^ ISBN 978-1598847185.

- ISBN 978-0822342809.

- ISBN 978-1137489319.

- ISBN 978-1137489319.

- ^ ISBN 978-1941920718.

- ISBN 978-1681444796.

- ISBN 978-8671910156.

- ^ Kuny Mena, Enrique (11 May 2003). "A 90 años del magnicidio Doctor Manuel Enrique Araujo" [90 Years after the Assassination of Doctor Manuel Enrique Araujo]. Vértice (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 17 June 2008. Retrieved 17 September 2020.

- ^ ISBN 978-1526100634.

- ^ ISBN 978-0679443995(2003), p. 58

- ^ Humanities, National Endowment for the (5 July 1914). "New-York tribune. [volume] (New York [N.Y.]) 1866-1924, July 05, 1914, Image 1" – via chroniclingamerica.loc.gov.

- ISBN 978-1526114440.

- ^ Delzell, p. 325; Roberts, p. 54; Rizi, p. 113

- ^ New York Times: "Bomb Menaces Life of Sacco Case Judge," September 27, 1932, accessed 20 December 2009

- ISBN 0-275-97891-5(2003) p. 168

- ^ Avrich, Paul, Sacco and Vanzetti: The Anarchist Background, Princeton University Press (1991), pp. 58–60

Bibliography

- Abidor, Mitchell, ed. (2016). Death to Bourgeois Society: The Propagandists of the Deed. ISBN 978-1629631127.

- Bantman, Constance (2018). "The Era of Propaganda by the Deed". In Adams, Matthew S.; Levy, Carl (eds.). The Palgrave Handbook of Anarchism. London: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 371–388. S2CID 150140014.

- LCCN 79-2750.

- Coolsaet, Rick (September 2004). "Anarchist outrages". Le Monde diplomatique.

- Gage, Beverly (2009). The Day Wall Street Exploded: A Story of America in its First Age of Terror. New York: ISBN 978-0199759286.

- Merriman, John (2009). The Dynamite Club. Boston: ISBN 978-0-618-55598-7.