Early modern human

Early modern human (EMH), or anatomically modern human (AMH),

Name and taxonomy

million years ago) |

The binomial name Homo sapiens was coined by Linnaeus, 1758.[10] The Latin noun homō (genitive hominis) means "human being", while the participle sapiēns means "discerning, wise, sensible".

The species was initially thought to have emerged from a predecessor within the genus Homo around 300,000 to 200,000 years ago.

Estimates for the split between the Homo sapiens line and combined Neanderthal/Denisovan line range from between 503,000 and 565,000 years ago;[15] between 550,000 and 765,000 years ago;[16] and (based on rates of dental evolution) possibly more than 800,000 years ago.[17]

Extant human populations have historically been divided into

Some sources show Neanderthals (H. neanderthalensis) as a subspecies (H. sapiens neanderthalensis).[21][22] Similarly, the discovered specimens of the H. rhodesiensis species have been classified by some as a subspecies (H. sapiens rhodesiensis), although it remains more common to treat these last two as separate species within the genus Homo rather than as subspecies within H. sapiens.[23]

All humans are considered to be a part of the subspecies

Age and speciation process

Derivation from H. erectus

The divergence of the lineage that would lead to H. sapiens out of

An mtDNA study in 2019 proposed an origin of modern humans in Botswana (and a Khoisan split) of around 200,000 years.[29] However, this proposal has been widely criticized by scholars,[30][31][32] with the recent evidence overall (genetic, fossil, and archaeological) supporting an origin for H. sapiens approximately 100,000 years earlier and in a broader region of Africa than the study proposes.[32]

In September 2019, scientists proposed that the earliest H. sapiens (and last common human ancestor to modern humans) arose between 350,000 and 260,000 years ago through a merging of populations in East and South Africa.[33][4]

An alternative suggestion defines H. sapiens cladistically as including the lineage of modern humans since the split from the lineage of Neanderthals, roughly 500,000 to 800,000 years ago.

The time of divergence between archaic H. sapiens and ancestors of Neanderthals and Denisovans caused by a

The derivation of a comparatively homogeneous single species of H. sapiens from more diverse varieties of

Since the 2000s, the availability of data from

Since the 1970s, the Omo remains, originally dated to some 195,000 years ago, have often been taken as the conventional cut-off point for the emergence of "anatomically modern humans". Since the 2000s, the discovery of older remains with comparable characteristics, and the discovery of ongoing hybridization between "modern" and "archaic" populations after the time of the Omo remains, have opened up a renewed debate on the age of H. sapiens in journalistic publications.[38][39][40][41][42] H. s. idaltu, dated to 160,000 years ago, has been postulated as an extinct subspecies of H. sapiens in 2003.[43][24] H. neanderthalensis, which became extinct about 40,000 years ago, was also at one point considered to be a subspecies, H. s. neanderthalensis.[24]

H. heidelbergensis, dated 600,000 to 300,000 years ago, has long been thought to be a likely candidate for the last common ancestor of the Neanderthal and modern human lineages. However, genetic evidence from the

Early Homo sapiens

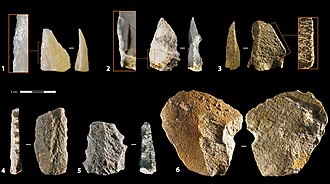

The term Middle Paleolithic is intended to cover the time between the first emergence of H. sapiens (roughly 300,000 years ago) and the period held by some to mark the emergence of full behavioral modernity (roughly by 50,000 years ago, corresponding to the start of the Upper Paleolithic).

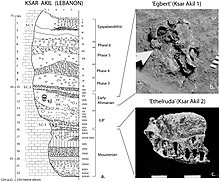

Many of the early modern human finds, like those of

The "gracile" or lightly built skeleton of anatomically modern humans has been connected to a change in behavior, including increased cooperation and "resource transport".[50][51]

There is evidence that the characteristic human brain development, especially the prefrontal cortex, was due to "an exceptional acceleration of

The ongoing admixture events within anatomically modern human populations make it difficult to estimate the age of the matrilinear and patrilinear most recent common ancestors of modern populations (Mitochondrial Eve and Y-chromosomal Adam). Estimates of the age of Y-chromosomal Adam have been pushed back significantly with the discovery of an ancient Y-chromosomal lineage in 2013, to likely beyond 300,000 years ago.[note 5] There have, however, been no reports of the survival of Y-chromosomal or mitochondrial DNA clearly deriving from archaic humans (which would push back the age of the most recent patrilinear or matrilinear ancestor beyond 500,000 years).[56][57][58]

Fossil teeth found at

Dispersal and archaic admixture

Dispersal of early H. sapiens begins soon after its emergence, as evidenced by the North African Jebel Irhoud finds (dated to around 315,000 years ago).[27][60] There is indirect evidence for H. sapiens presence in West Asia around 270,000 years ago.[61]

The Florisbad Skull from Florisbad, South Africa, dated to about 259,000 years ago, has also been classified as representing early H. sapiens.[62][63]Scerri (2018), pp. 582–594[4]

In September 2019, scientists proposed that the earliest H. sapiens (and last common human ancestor to modern humans) arose between 350,000 and 260,000 years ago through a merging of populations in East and South Africa.[33][4]

Among extant populations, the

H. s. idaltu, found at Middle Awash in Ethiopia, lived about 160,000 years ago,[64] and H. sapiens lived at Omo Kibish in Ethiopia about 233,000-195,000 years ago.[65][2] Two fossils from Guomde, Kenya, dated to at least (and likely more than) 180,000 years ago[62] and (more precisely) to 300–270,000 years ago,[4] have been tentatively assigned to H. sapiens and similarities have been noted between them and the Omo Kibbish remains.[62] Fossil evidence for modern human presence in West Asia is ascertained for 177,000 years ago,[66] and disputed fossil evidence suggests expansion as far as East Asia by 120,000 years ago.[67][68]

In July 2019, anthropologists reported the discovery of 210,000 year old remains of a H. sapiens and 170,000 year old remains of a H. neanderthalensis in Apidima Cave, Peloponnese, Greece, more than 150,000 years older than previous H. sapiens finds in Europe.[69][70][71]

A significant dispersal event, within Africa and to West Asia, is associated with the African megadroughts during MIS 5, beginning 130,000 years ago.[72] A 2011 study located the origin of basal population of contemporary human populations at 130,000 years ago, with the Khoi-San representing an "ancestral population cluster" located in southwestern Africa (near the coastal border of Namibia and Angola).[73]

While early modern human expansion in

Evidence for the overwhelming contribution of this "recent" (

In September 2019, scientists reported the computerized determination, based on 260

Anatomy

Generally, modern humans are more lightly built (or more "gracile") than the more "robust"

Anatomical modernity

The term "anatomically modern humans" (AMH) is used with varying scope depending on context, to distinguish "anatomically modern" Homo sapiens from

In this more narrow definition of H. sapiens, the subspecies

A further division of AMH into "early" or "robust" vs. "post-glacial" or "

Braincase anatomy

The cranium lacks a pronounced

Modern humans commonly have a steep, even vertical forehead whereas their predecessors had foreheads that sloped strongly backwards.[99] According to Desmond Morris, the vertical forehead in humans plays an important role in human communication through eyebrow movements and forehead skin wrinkling.[100]

Brain size in both Neanderthals and AMH is significantly larger on average (but overlapping in range) than brain size in H. erectus. Neanderthal and AMH brain sizes are in the same range, but there are differences in the relative sizes of individual brain areas, with significantly larger visual systems in Neanderthals than in AMH.[101][note 9]

Jaw anatomy

Compared to archaic people, anatomically modern humans have smaller, differently shaped teeth.[104][105] This results in a smaller, more receded dentary, making the rest of the jaw-line stand out, giving an often quite prominent chin. The central part of the mandible forming the chin carries a triangularly shaped area forming the apex of the chin called the mental trigon, not found in archaic humans.[106] Particularly in living populations, the use of fire and tools requires fewer jaw muscles, giving slender, more gracile jaws. Compared to archaic people, modern humans have smaller, lower faces.

Body skeleton structure

The body skeletons of even the earliest and most robustly built modern humans were less robust than those of Neanderthals (and from what little we know from Denisovans), having essentially modern proportions. Particularly regarding the long bones of the limbs, the distal bones (the radius/ulna and tibia/fibula) are nearly the same size or slightly shorter than the proximal bones (the humerus and femur). In ancient people, particularly Neanderthals, the distal bones were shorter, usually thought to be an adaptation to cold climate.[107] The same adaptation is found in some modern people living in the polar regions.[108]

Recent evolution

Following the

Some climatic adaptations, such as

Physiological or phenotypical changes have been traced to Upper Paleolithic mutations, such as the East Asian variant of the

Recent divergence of Eurasian lineages was sped up significantly during the

Examples for still later adaptations related to

An even more recent adaptation has been proposed for the Austronesian Sama-Bajau, developed under selection pressures associated with subsisting on freediving over the past thousand years or so.[123][124]

Behavioral modernity

There is considerable debate regarding whether the earliest anatomically modern humans behaved similarly to recent or existing humans.

The term "behavioral modernity" is somewhat disputed. It is most often used for the set of characteristics marking the Upper Paleolithic, but some scholars use "behavioral modernity" for the emergence of H. sapiens around 200,000 years ago,[127] while others use the term for the rapid developments occurring around 50,000 years ago.[128][129][130] It has been proposed that the emergence of behavioral modernity was a gradual process.[131][132][133][134][135]

Examples of behavioural modernity

The equivalent of the Eurasian Upper Paleolithic in African archaeology is known as the

In addition, a variety of other evidence of abstract imagery, widened subsistence strategies, and other "modern" behaviors has been discovered in Africa, especially South, North, and East Africa, predating 50,000 years ago (with some predating 100,000 years ago). The Blombos Cave site in South Africa, for example, is famous for rectangular slabs of ochre engraved with

In 2008, an ochre processing workshop likely for the production of paints was uncovered dating to ca. 100,000 years ago at Blombos Cave, South Africa. Analysis shows that a liquefied pigment-rich mixture was produced and stored in the two abalone shells, and that ochre, bone, charcoal, grindstones and hammer-stones also formed a composite part of the toolkits. Evidence for the complexity of the task includes procuring and combining raw materials from various sources (implying they had a mental template of the process they would follow), possibly using pyrotechnology to facilitate fat extraction from bone, using a probable recipe to produce the compound, and the use of shell containers for mixing and storage for later use.[157][158][159] Modern behaviors, such as the making of shell beads, bone tools and arrows, and the use of ochre pigment, are evident at a Kenyan site by 78,000-67,000 years ago.[160] Evidence of early stone-tipped projectile weapons (a characteristic tool of Homo sapiens), the stone tips of javelins or throwing spears, were discovered in 2013 at the Ethiopian site of Gademotta, and date to around 279,000 years ago.[161]

Expanding subsistence strategies beyond big-game hunting and the consequential diversity in tool types have been noted as signs of behavioral modernity. A number of South African sites have shown an early reliance on aquatic resources from fish to shellfish. Pinnacle Point, in particular, shows exploitation of marine resources as early as 120,000 years ago, perhaps in response to more arid conditions inland.[162] Establishing a reliance on predictable shellfish deposits, for example, could reduce mobility and facilitate complex social systems and symbolic behavior. Blombos Cave and Site 440 in Sudan both show evidence of fishing as well. Taphonomic change in fish skeletons from Blombos Cave have been interpreted as capture of live fish, clearly an intentional human behavior.[145]

Humans in North Africa (Nazlet Sabaha, Egypt) are known to have dabbled in chert mining, as early as ≈100,000 years ago, for the construction of stone tools.[163][164]

Evidence was found in 2018, dating to about 320,000 years ago at the site of Olorgesailie in Kenya, of the early emergence of modern behaviors including: the trade and long-distance transportation of resources (such as obsidian), the use of pigments, and the possible making of projectile points. The authors of three 2018 studies on the site observe that the evidence of these behaviors is roughly contemporary with the earliest known Homo sapiens fossil remains from Africa (such as at Jebel Irhoud and Florisbad), and they suggest that complex and modern behaviors began in Africa around the time of the emergence of Homo sapiens.[165][166][167]

In 2019, further evidence of Middle Stone Age complex projectile weapons in Africa was found at Aduma, Ethiopia, dated 100,000–80,000 years ago, in the form of points considered likely to belong to darts delivered by spear throwers.[168]

Pace of progress during Homo sapiens history

Homo sapiens technological and cultural progress appears to have been very much faster in recent millennia than in Homo sapiens early periods. The pace of development may indeed have accelerated, due to massively larger population (so more humans extant to think of innovations), more communication and sharing of ideas among human populations, and the accumulation of thinking tools. However it may also be that the pace of advancements always looks relatively faster to humans in the time they live, because previous advances are unrecognised.[169]

Notes

- ^ Based on Schlebusch et al., "Southern African ancient genomes estimate modern human divergence to 350,000 to 260,000 years ago",[6] Fig. 3 (H. sapiens divergence times) and Stringer (2012),[7] (archaic admixture).

- ^ This is a matter of convention (rather than a factual dispute), and there is no universal consensus on terminology. Some scholars include humans of up to 600,000 years ago under the same species. See Bryant (2003), p. 811.[11] See also Tattersall (2012), Page 82 (cf. Unfortunately this consensus in principle hardly clarifies matters much in practice. For there is no agreement on what the 'qualities of a man' actually are," [...]).[12]

- ^ Werdelin[13] citing Lieberman et al.[14]

- H. sapiens idaltu (2003). The name H. s. sapiens is due to Linnaeus (1758), and refers by definition the subspecies of which Linnaeus himself is the type specimen. However, Linnaeus postulated four other extant subspecies, viz. H. s. afer, H. s. americanus, H. s. asiaticus and H. s. ferus for Africans, Americans, Asians and Malay. This classification remained in common usage until the mid 20th century, sometimes alongside H. s. tasmanianus for Australians. See, for example, Bailey, 1946;[18] Hall, 1946.[19] The division of extant human populations into taxonomic subspecies was gradually given up in the 1970s (for example, Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia[20]).

- ^ (95% confidence interval 237–581 kya)[55]

- ^ "Although none of the Qesem teeth shows a suite of Neanderthal characters, a few traits may suggest some affinities with members of the Neanderthal evolutionary lineage. However, the balance of the evidence suggests a closer similarity with the Skhul/Qafzeh dental material, although many of these resemblances likely represent plesiomorphous features."[59]

- ^ "Currently available genetic and archaeological evidence is generally interpreted as supportive of a recent single origin of modern humans in East Africa."[80]

- ^ This is a question of conventional terminology, not one of a factual disagreement. Pääbo (2014) frames this as a debate that is unresolvable in principle, "since there is no definition of species perfectly describing the case."[92]

- ^ Contemporary human endocranial volume averages at 1,350 cm3 (82 cu in), with significant differences between populations, global group means range 1,085–1,580 cm3 (66.2–96.4 cu in).[102] Neanderthal average is close to 1,450 cm3 (88 cu in) (male average 1,600 cm3 (98 cu in), female average 1,300 cm3 (79 cu in)), with a range extending up to 1,736 cm3 (105.9 cu in) (Amud 1).[103]

- ^ "Based on 45 long bones from maximally 14 males and 7 females, Neanderthals' height averages between 164 and 168 (males) resp. 152 to 156 cm (females). This height is indeed 12–14 cm lower than the height of post-WWII Europeans, but compared to Europeans some 20,000 or 100 years ago, it is practically identical or even slightly higher."[109]

- ^ Malay, 20–24 (N= m:749 f:893, Median= m:166 cm (5 ft 5+1⁄2 in) f:155 cm (5 ft 1 in), SD= m:6.46 cm (2+1⁄2 in) f:6.04 cm (2+1⁄2 in))[110]

- ^ "Specifically, genes in the LCP [lipid catabolic process] term had the greatest excess of NLS in populations of European descent, with an average NLS frequency of 20.8±2.6% versus 5.9±0.08% genome wide (two-sided t-test, P<0.0001, n=379 Europeans and n=246 Africans). Further, among examined out-of-Africa human populations, the excess of NLS [Neanderthal-like genomic sites] in LCP genes was only observed in individuals of European descent: the average NLS frequency in Asians is 6.7±0.7% in LCP genes versus 6.2±0.06% genome wide."[112]

- ^ Traits affected by the mutation are sweat glands, teeth, hair thickness and breast tissue.[114][115]

- ^ "We offer an alternative hypothesis that suggests that hominid expansion into regions of cold climate produced change in head shape. Such change in shape contributed to the increased cranial volume. Bioclimatic effects directly upon body size (and indirectly upon brain size) in combination with cranial globularity appear to be a fairly powerful explanation of ethnic group differences." (figure in Beals, p304)[118]

References

- ISBN 1489915079.

- ^ PMID 35022610.

- PMID 28552208.

- ^ PMID 31506422.

- ^ PMID 30007846.

- ^ PMID 28971970.

- S2CID 4420496.

- ^ PMID 29376123.

- ^ Harrod, James. "Harrod (2014) Suppl File Table 1 mtDNA language myth Database rev May 17 2019.doc". Mother Tongue.

- ^ Linné, Carl von (1758). Systema naturæ. Regnum animale (10th ed.). Sumptibus Guilielmi Engelmann. pp. 18, 20. Retrieved 2019-05-06.

- ISBN 0761925147.

- ISBN 978-1137000385.

- ISBN 978-0520257214.

- PMID 11805284.

- PMID 29562232.

- S2CID 4467094.

- PMID 31106274.

- ^ Bailey, John Wendell (1946). The Mammals of Virginia. p. 356.

- PMID 20247535.

- ISBN 978-0442784782.

- PMID 19805257.

- PMID 14745010.

- ^ "Homo neanderthalensis King, 1864". Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Human Evolution. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. 2013. pp. 328–331.

- ^ a b c d Rafferty, John P. "Homo sapiens sapiens". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-08-11.

- bioRxiv 10.1101/145409.

- PMID 28971970.

- ^ . Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- ^ Stringer (2016), p. 20150237; Sample (2017); Hublin et al. (2017), pp. 289–292; Scerri (2018), pp. 582–594

- S2CID 204946938.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- ^ Woodward, Aylin (28 October 2019). "New Study Pinpoints The Ancestral Homeland of All Humans Alive Today". ScienceAlert.com. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- ^ a b Yong, Ed (28 October 2019). "Has Humanity's Homeland Been Found?". The Atlantic. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- ^ a b c Zimmer, Carl (10 September 2019). "Scientists Find the Skull of Humanity's Ancestor – on a Computer – By comparing fossils and CT scans, researchers say they have reconstructed the skull of the last common forebear of modern humans". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- PMID 28784789.

- S2CID 5223638.

- ^ PMID 20448178.

- PMID 21944045.

- ^ "New Clues Add 40,000 Years to Age of Human Species". www.nsf.gov. NSF – National Science Foundation.

- ^ "Age of ancient humans reassessed". BBC News. February 16, 2005. Retrieved April 10, 2010.

- ^ "The Oldest Homo Sapiens: Fossils Push Human Emergence Back To 195,000 Years Ago". ScienceDaily. February 28, 2005. Retrieved 2019-05-06.

- (PDF) from the original on 2020-07-18.

- PMID 8994844.

- ^ Human evolution: the fossil evidence in 3D, by Philip L. Walker and Edward H. Hagen, Dept. of Anthropology, University of California, Santa Barbara. Retrieved April 5, 2005.

- S2CID 4467094.

- S2CID 4459329.

- ISBN 978-1841196978.

- PMID 14504393.

- ^ PMID 21179161.

- S2CID 9039428.

- ISBN 978-0306480003.

- ISBN 978-0199738182.

- PMID 24866127.

- ISBN 978-3896460400.

- ISBN 3893083812.

- PMID 23453668. Archived from the original(PDF) on 24 September 2019. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- S2CID 13581775.

- ^ Hill, Deborah (16 March 2004). "No Neandertals in the Gene Pool". Science. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- PMID 15024415.

- S2CID 3106938.

- ^ Hublin et al. 2017, pp. 289–292.

- PMID 28675384.

- ^ a b c d Stringer 2016, p. 20150237.

- ^ Sample 2017.

- S2CID 4432091.

- ^ "Fossil Reanalysis Pushes Back Origin of Homo sapiens". Scientific American. 17 February 2005. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- ^ Mehta, Ankita (26 January 2018). "A 177,000-year-old jawbone fossil discovered in Israel is oldest human remains found outside Africa". International Business Times. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- PMID 29217544.

- ^ Kuo, Lily (10 December 2017). "Early humans migrated out of Africa much earlier than we thought". Quartz. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- ^ Zimmer, Carl (10 July 2019). "A Skull Bone Discovered in Greece May Alter the Story of Human Prehistory – The bone, found in a cave, is the oldest modern human fossil ever discovered in Europe. It hints that humans began leaving Africa far earlier than once thought". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ Staff (10 July 2019). "'Oldest remains' outside Africa reset human migration clock". Phys.org. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- S2CID 195873640.

- PMID 24236171.

- PMID 21383195.

- ^ PMID 24039825.

- ^ Posth, et al., 2016; Kamin, et al., 2015; Vai, et al., 2019; Haber, et al., 2019

- (PDF) from the original on 2019-04-28.

- ^ St. Fleu, Nicholas (July 19, 2017). "Humans First Arrived in Australia 65,000 Years Ago, Study Suggests". The New York Times.

- S2CID 148777016.

- PMID 30082377.

- PMID 16826514.

- S2CID 220100436.

- ^ Haber, et al., 2019.

- PMID 27032491.

- PMID 23082212.

- PMID 25341783.

- The New Scientist. Retrieved 2019-05-06.

- PMID 26886800.

- PMID 24336922.

- S2CID 23003860.

- ISBN 978-0198739906 – via Google Books.

- ISBN 978-0867202687 – via Google Books.

- ^ Pääbo, Svante (2014). Neanderthal Man: In Search of Lost Genomes. New York: Basic Books. p. 237.

- ^ Sanders, Robert (11 June 2003). "160,000-year-old fossilized skulls uncovered in Ethiopia are oldest anatomically modern humans". UC Berkeley News. Retrieved 2019-05-07.

- S2CID 4432091.

- S2CID 26693109.

- PMID 18087044.

- ^ Bhupendra, P. (April 2019). "Forehead Anatomy". Medscape references. Retrieved 2019-05-06.

- ^ "How to ID a modern human?". News, 2012. Natural History Museum, London. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ Encarta, Human Evolution. Archived from the original on 29 October 2009.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|work=ignored (help) - ISBN 978-0312338534.

- PMID 23486442.

- S2CID 162406199.

- ISBN 978-0122619205.

- S2CID 26123427.

- PMID 19977113.

- ISBN 978-0471319283.

- S2CID 2437566.

- PMID 16596600.

- PMID 9850627.

- (PDF) from the original on 2017-02-24.

- ^ Wade, N (2006-03-07). "Still Evolving, Human Genes Tell New Story". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-07-10.

- PMID 24690587.

- ^ Michael Dannemann 1 and Janet Kelso, "The Contribution of Neanderthals to Phenotypic Variation in Modern Humans", The American Journal of Human Genetics 101, 578–589, October 5, 2017.

- PMID 23415220.

- ^ Wade, Nicholas (14 February 2013). "East Asian Physical Traits Linked to 35,000-Year-Old Mutation". The New York Times. Retrieved 2019-05-06.

- ^ PMID 22923467.

- S2CID 10087710.

- ^ S2CID 86147507.

- PMID 22053534. Archived from the originalon 2014-10-11.

- PMID 20089146.

- PMID 28426286.

- S2CID 3329285.

- PMID 29677510.

- S2CID 18731746.

- S2CID 10402296.

- ISBN 978-0313364303.

- ISBN 1868144178.

- Later Stone Age and Upper Paleolithic.

- PMID 16772383.

- S2CID 142517998.

- S2CID 42968840.

- S2CID 11081605.

- S2CID 4387442.

- (PDF) from the original on 2017-08-29.

- PMID 21179418.

- ^ St. Fleur, Nicholas (12 September 2018). "Oldest Known Drawing by Human Hands Discovered in South African Cave". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- PMID 22847420.

- S2CID 34833884.

- ^ S2CID 4323569.

- PMID 17785420.

- ISBN 978-0691115320.

- S2CID 31169551.

- PMID 19487016.

- PMID 20194764.

- ^ S2CID 42968840.

- S2CID 32356688.

- PMID 15656934.

- PMID 23498114.

- .

- ^ Wadley, Lyn (2008). "The Howieson's Poort industry of Sibudu Cave". South African Archaeological Society Goodwin Series. 10.

- S2CID 162438490.

- .

- .

- S2CID 224889105.

- PMID 7725100.

- S2CID 43916405

- ^ Amos, Jonathan (13 October 2011). "A Cultural Leap at the Dawn of Humanity – Ancient 'paint factory' unearthed". BBC News. Retrieved 13 October 2011.

- ^ Vastag, Brian (13 October 2011). "South African cave yields paint from dawn of humanity". The Washington Post. Retrieved 13 October 2011.

- S2CID 40455940.

- ^ Shipton C, d'Errico F, Petraglia M, et al. (2018). 78,000-year-old record of Middle and Later Stone Age innovation in an East African tropical forest. Nature Communications

- PMID 24236011.

- S2CID 4387442.

- ^ "5 Oldest Mines in the World: A Casual Survey". Archived from the original on 2019-01-05. Retrieved 2019-09-11.

- ISBN 978-1910561034.

- ^ Chatterjee, Rhitu (15 March 2018). "Scientists Are Amazed By Stone Age Tools They Dug Up In Kenya". NPR. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ^ Yong, Ed (15 March 2018). "A Cultural Leap at the Dawn of Humanity – New finds from Kenya suggest that humans used long-distance trade networks, sophisticated tools, and symbolic pigments right from the dawn of our species". The Atlantic. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- PMID 29545508.

- PMID 31071181.

- ^ Douglas, Kate (March 24, 2012). "Puzzles of Evolution: Why was technological development so slow?". New Scientist. Archived from the original on April 13, 2016. Retrieved May 4, 2022.

{{cite magazine}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)

Sources

- Haber M, Jones AL, Connel BA, Asan, Arciero E, Huanming Y, Thomas MG, Xue Y, Tyler-Smith C (June 2019). "A Rare Deep-Rooting D0 African Y-chromosomal Haplogroup and its Implications for the Expansion of Modern Humans Out of Africa". PMID 31196864.

- Hublin, Jean-Jacques; Ben-Ncer, Abdelouahed; Bailey, Shara E.; Freidline, Sarah E.; Neubauer, Simon; Skinner, Matthew M.; Bergmann, Inga; Le Cabec, Adeline; Benazzi, Stefano; Harvati, Katerina; Gunz, Philipp (2017). "New fossils from Jebel Irhoud, Morocco and the pan-African origin of Homo sapiens" (PDF). S2CID 256771372.

- Kamin M, Saag L, Vincente M, et al. (April 2015). "A recent bottleneck of Y chromosome diversity coincides with a global change in culture". PMID 25770088.

- Posth C, Renaud G, Mittnik M, Drucker DG, Rougier H, Cupillard C, Valentin F, Thevenet C, Furtwängler A, Wißing C, Francken M, Malina M, Bolus M, Lari M, Gigli E, Capecchi G, Crevecoeur I, Beauval C, Flas D, Germonpré M, van der Plicht J, Cottiaux R, Gély B, Ronchitelli A, Wehrberger K, Grigorescu D, Svoboda J, Semal P, Caramelli D, Bocherens H, Harvati K, Conard NJ, Haak W, Powell A, Krause J (2016). "Pleistocene Mitochondrial Genomes Suggest a Single Major Dispersal of Non-Africans and a Late Glacial Population Turnover in Europe". S2CID 140098861.

- Sample, Ian (7 June 2017). "Oldest Homo sapiens bones ever found shake foundations of the human story". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- Scerri, M.L.; et al. (2018). "Did Our Species Evolve in Subdivided Populations across Africa, and Why Does It Matter?". PMID 30007846.

- Stringer, C. (2016). "The origin and evolution of Homo sapiens". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 371 (1698): 20150237. PMID 27298468.

- Vai S, Sarno S, Lari M, Luiselli D, Manzi G, Gallinaro M, Mataich S, Hübner A, Modi A, Pilli E, Tafuri MA, Caramelli D, di Lernia S (March 2019). "Ancestral mitochondrial N lineage from the Neolithic 'green' Sahara". Sci Rep. 9 (1): 3530. PMID 30837540.

Further reading

- Reich, David (2018). Who We Are And How We Got Here – Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past. ISBN 978-1101870327.[1]

External links

- Human Timeline (Interactive) – Smithsonian, National Museum of Natural History (August 2016).

Media related to Early modern human at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Early modern human at Wikimedia Commons Data related to Early modern human at Wikispecies

Data related to Early modern human at Wikispecies

- ^ Diamond, Jared (April 20, 2018). "A Brand-New Version of Our Origin Story". The New York Times. Retrieved April 23, 2018.