Roman sculpture

The study of Roman sculpture is complicated by its relation to

The strengths of Roman sculpture are in portraiture, where they were less concerned with the ideal than the Greeks or Ancient Egyptians, and produced very characterful works, and in narrative relief scenes. Examples of Roman sculpture are abundantly preserved, in total contrast to Roman painting, which was very widely practiced but has almost all been lost.

Most statues were actually far more lifelike and often brightly colored when originally created; the raw stone surfaces found today is due to the pigment being lost over the centuries.[2]

Development

Right image: Section and detail of the Column of Marcus Aurelius, Rome, 177–180 AD, with scenes from the Marcomannic Wars

Early Roman art was influenced by the art of Greece and that of the neighbouring

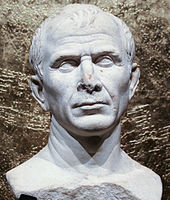

A native Italian style can be seen in the tomb monuments of prosperous middle-class Romans, which very often featured portrait busts, and portraiture is arguably the main strength of Roman sculpture. There are no survivals from the tradition of masks of ancestors that were worn in processions at the funerals of the great families and otherwise displayed in the home, but many of the busts that survive must represent ancestral figures, perhaps from the large family tombs like the Tomb of the Scipios or the later mausolea outside the city. The famous "Capitoline Brutus", a bronze head supposedly of Lucius Junius Brutus is very variously dated, but taken as a very rare survival of Italic style under the Republic, in the preferred medium of bronze.[7] Similarly stern and forceful heads are seen in the coins of the consuls, and in the Imperial period coins as well as busts sent around the Empire to be placed in the basilicas of provincial cities were the main visual form of imperial propaganda; even Londinium had a near-colossal statue of Nero, though far smaller than the 30-metre-high Colossus of Nero in Rome, now lost.[8] The Tomb of Eurysaces the Baker, a successful freedman (c. 50–20 BC) has a frieze that is an unusually large example of the "plebeian" style.[9]

The Romans did not generally attempt to compete with free-standing Greek works of heroic exploits from history or mythology, but from early on produced historical works in

All forms of luxury small sculpture continued to be patronized, and quality could be extremely high, as in the silver Warren Cup, glass Lycurgus Cup, and large cameos like the Gemma Augustea, Gonzaga Cameo and the "Great Cameo of France".[11] For a much wider section of the population, moulded relief decoration of pottery vessels and small figurines were produced in great quantity and often considerable quality.[12]

After moving through a late 2nd century "baroque" phase,[13] in the 3rd century, Roman art largely abandoned, or simply became unable to produce, sculpture in the classical tradition, a change whose causes remain much discussed. Even the most important imperial monuments now showed stumpy, large-eyed figures in a harsh frontal style, in simple compositions emphasizing power at the expense of grace. The contrast is famously illustrated in the Arch of Constantine of 315 in Rome, which combines sections in the new style with roundels in the earlier full Greco-Roman style taken from elsewhere, and the Four Tetrarchs (c. 305) from the new capital of Constantinople, now in Venice. Ernst Kitzinger found in both monuments the same "stubby proportions, angular movements, an ordering of parts through symmetry and repetition and a rendering of features and drapery folds through incisions rather than modelling... The hallmark of the style wherever it appears consists of an emphatic hardness, heaviness and angularity — in short, an almost complete rejection of the classical tradition".[14]

This revolution in style shortly preceded the period in which

-

Etruscan sarcophagus, 3rd century BCE

-

The "Capitoline Brutus", probably late 4th to early 3rd century BC, possibly 1st century BC.[16]

-

AMuseo Pio-Clementino) in the Vatican Museums.

-

The Patrician Torlonia bust, believed to be of Cato the Elder. 1st century BC

-

The Orator, c. 100 BC, an Etrusco-Roman bronze statue depicting Aule Metele (Latin: Aulus Metellus), an Etruscan man wearing a Roman toga while engaged in rhetoric; the statue features an inscription in the Etruscan alphabet

-

Bronze bust of Roman Isis priest, formerly identified as Scipio Africanus, mid 1st century BC[19][20]

-

The so-called "imagines) of deceased ancestors; marble, late 1st century BC; head (not belonging): mid 1st century BC.

-

Rhone River near Arles, c. 46 BC

-

Roman,New Comedy, 1st century BC – early 1st century AD, Princeton University Art Museum

-

The cameo gem known as the "Great Cameo of France", c. 23 CE, with an allegory of Augustus and his family

-

Bust ofEmperor Claudius, c. 50 CE, (reworked from a bust of emperor Caligula), It was found in the so-called Otricoli basilica in Lanuvium, Italy, Vatican Museums

-

Tomb relief of the Decii, 98–117 CE

-

Statue of Mars from the Forum of Nerva, early 2nd century AD, based on an Augustan-era original that in turn used a Hellenistic Greek model of the 4th century BC, Capitoline Museums[21]

-

Polychrome marble statue depicting the goddessIstanbul Archaeological Museum

-

Statue of Antinous (Delphi), depicting Antinous, polychrome Parian marble, made during the reign of Hadrian (r. 117-138 AD)

-

Male torso with legs to the knees, discovered on the site of the Odeon of Lyon in 1964. Marble. Lyon, Lugdunum

-

Male torso discovered on the site of the Odeon of Lyon in 1964. Marble. Lyon, Lugdunum.

-

Ancient bust of Roman emperor Lucius Verus (r. 161–169), a natural blond who would sprinkle gold dust in his hair to make it even blonder,[22] Bardo National Museum, Tunis

-

Remnants of a Roman bust of a youth with a blond beard, perhaps depicting Roman emperor Commodus (r. 177–192), National Archaeological Museum, Athens

-

Marcus Aurelius receiving the submission of vanquished foes from the Marcomannic Wars, a relief from his now destroyed triumphal arch in Rome, Capitoline Museums, 177-180 AD

-

Private portrait with both individualized and unforgiving naturalism and stylized influence of portraits of the emperors Hadrian and Antoninus Pius in his beard and hairstyle.

-

Ancient Roman statue of Isis, in the Collection of Greek and Roman Antiquities in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna; first half of the 2nd century AD, found in Naples, Italy; made out of black and white marble.

-

Marble table support adorned by a group includingAsia Minor workshop, 170-180 AD, National Archaeological Museum, Athens, Greece

-

The Farnese Hercules, probably an enlarged copy made in the early 3rd century AD and signed by a certain Glykon, from an original by Lysippos (or one of his circle) that would have been made in the 4th century BC; The copy was made for the Baths of Caracalla in Rome (dedicated in 216 AD), where it was recovered in 1546

-

Ancient Roman statue of emperor Balbinus, dating from 238 AD, on display in the Archaeological Museum of Piraeus (Athens)

-

Bronze of Trebonianus Gallus dating from the time of his reign as Roman Emperor, the only surviving near-complete full-size 3rd-century Roman bronze (Metropolitan Museum of Art)[23]

-

San Marco, Venice

-

Head and other fragments aMusei Capitolini(Rome)

-

A marble portrait bust of a Roman matron, early 4th century AD, Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg

-

Bust depicting an idealized portrait of Menander of Ephesus, 4th century AD, Ephesus Archaeological Museum

-

Detail of a sarcophagus depicting the Christian belief in the multiplication of bread loaves and fish by Jesus Christ, c. 350-375 AD, Vatican Museums

-

Boxwoodsortie; Western Roman Empire, early 5th century AD

-

Portrait of an unknown man, found in theAgora of Athens, dating from around 400-450 AD; National Archaeological Museum, Athens

-

Bust of Eastern Roman Emperor Theodosius II (r. 408–450 AD); marble, 5th century AD

-

Bust of an Eastern Roman lady (Galla Placidia?) in the Musée Saint-Raymond de Toulouse, 5th century AD

Portraiture

Among the many museums with examples of Roman portrait sculpture, the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the British Museum in London are especially noteworthy.

Religious and funerary art

The time taken to make them encouraged the use of standard subjects, to which inscriptions might be added to personalize them, and portraits of the deceased were slow to appear. The sarcophagi offer examples of intricate reliefs that depict scenes often based on

Scenes from Roman sarcophagi

-

Scenes of Orphic religion (2nd century)

-

Portonaccio sarcophagus with a battle

-

Dionysus riding a panther and accompanied by attendants, 220-230 AD

-

Children playing with nuts (3rd century)

-

Sarcophagus with the Calydonian hunt,Palazzo dei Senatori - Musei Capitolini, Rome.

-

Sarcophagus with the Four Seasons allegory

(3rd century),Palazzo dei Senatori - Musei Capitolini, Rome. -

Sarcophagus of the Quinta Flavia Severina,Palazzo dei Senatori - Musei Capitolini, Rome.

-

Early Christian marble sarcophagus with a high-relief representing scenes from the Old and the New Testament, c. 310 AD

-

Cast of Christ's trial before Pilate, with Pilate about to wash his hands. Detail from the Early Christian Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus (d. 359)

Gardens and baths

A number of well-known large stone vases sculpted in relief from the Imperial period were apparently mostly used as garden ornaments; indeed many statues were also placed in gardens, both public and private. Sculptures recovered from the site of the Gardens of Sallust, opened to the public by Tiberius, include:

- the Obelisco Sallustiano, a Roman copy of an Egyptian obelisk which now stands in front of the Trinità dei Monti church above the Piazza di Spagna at the top of the Spanish Steps

- the Borghese Vase, discovered there in the 16th century.

- the sculptures known as the Dying Gaul and the Gaul Killing Himself and His Wife, marble copies of parts a famous Hellenistic group in bronze commissioned for Pergamon in about 228 BC.

- the Ludovisi Throne (probably an authentic Greek piece in the Severe style), found in 1887, and the Boston Throne, found in 1894.

- the Crouching Amazon, found in 1888 near the via Boncompagni, about twenty-five meters from the via Quintino Sella (Museo Conservatori).

Found in the Gardens of Sallust and the Gardens of Maecenas:

-

FallingNiobid, discovered in the site in 1906 (Museo Nazionale Romano), a Greek original[29]

-

Caryatid statue,Palazzo dei Senatori - Musei Capitolini, Rome.

-

Fountain in the form of a horn-shaped drinking cup (rhyton),Palazzo dei Senatori - Musei Capitolini, Rome.

-

Child with a theatre mask, for a garden or house,Palazzo Nuovo - Musei Capitolini, Rome.

Technology

Scenes shown on reliefs such as that of

Architecture

Compared to the Greeks, the Romans made less use of stone sculpture on buildings, apparently having few

The architectural writer Vitruvius is oddly reticent on the architectural use of sculpture, mentioning only a few examples, though he says that an architect should be able to explain the meaning of architectural ornament and gives as an example the use of caryatids.[30]

See also

- Ancient Roman pottery

- Classical sculpture

- Gallo-Roman art

- History of sculpture

- Roman art

- Roman engineering

- Roman technology

Notes

- ^ Hennig, 94–95

- ^ "True Colors | Arts & Culture | Smithsonian Magazine".

- ^ Strong, 58–63; Hennig, 66–69

- ^ Hennig, 24

- JSTOR 4238630.

- 's prosecution details his depredations of art collections at great length.

- ^ Henig, 23–24; Strong, 47

- ^ Henig, 66–71

- ^ Hennig, 66; Strong, 125

- ^ Henig, 73–82;Strong, 48–52, 80–83, 108–117, 128–132, 141–159, 177–182, 197–211

- ^ Henig, Chapter 6; Strong, 303–315

- ^ Henig, Chapter 8

- ^ Strong, 171–176, 211–214

- ^ Kitzinger, 9 (both quotes), more generally his Ch 1; Strong, 250–257, 264–266, 272–280; also on the Arch of Constantine, Elsner, 98–101

- ^ Strong, 287–291, 305–308, 315–318; Henig, 234–240

- ^ Strong, 47

- ISBN 978-1-4051-2153-8. Plate 12.2 on p. 204.

- ^ Coarelli, Filippo (1987), I Santuari del Lazio in età repubblicana. NIS, Rome, pp 35-84.

- ^ "Individual object 13585: Portraitbüste eines Mannes (Isis- Priester)". arachne.uni-koeln.de. University of Cologne Archaeological Institute. Retrieved 2022-01-15.

- ^ "print; drawing book | British Museum". The British Museum. Retrieved 2022-01-15.

- ^ Capitoline Museums. "Colossal statue of Mars Ultor also known as Pyrrhus - Inv. Scu 58." Capitolini.info. Accessed 8 October 2016.

- ISBN 0-415-10754-7, pp 27-28.

- ^ Bronze portrait of Trebonianus Gallus, 05.30

- ^ Karl Galinsky, Augustan Culture: An Interpretive Introduction (Princeton University Press, 1996), p. 141.

- ^ Hennig, 95–96

- ^ The Sarcophagus of Lucius Cornelius Scipio Barbatus is a rare example from much earlier

- ^ Hennig, 93–94

- ^ Hennig, 93–94

- ^ T. Ashby, "Recent Excavations in Rome", CQ 2/2 (1908) p.49.

- ^ Brunilde Sismondo Ridgway, Prayers in Stone: Greek Architectural Sculpture ca. 600-100 B.C.E. (University of California Press, 1999), pp. 13–14 online and 145.

References

- ISBN 0226571696, 9780226571690, google books

- Henig, Martin (ed, Ch 3, "Sculpture" by Anthony Bonanno), A Handbook of Roman Art, Phaidon, 1983, ISBN 0714822140

- ISBN 0571111548(US: Cambridge UP, 1977)

- Strong, Donald, et al., Roman Art, 1995 (2nd edn.), Yale University Press (Penguin/Yale History of Art), ISBN 0300052936

- Williams, Dyfri. Masterpieces of Classical Art, 2009, British Museum Press, ISBN 9780714122540

Further reading

- Conlin, Diane Atnally. The Artists of the Ara Pacis: The Process of Hellenization In Roman Relief Sculpture. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997.

- Fejfer, Jane. Roman Portraits In Context. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2008.

- Flower, Harriet I. Ancestor Masks and Aristocratic Power In Roman Culture. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996.

- Gruen, Erich S. Culture and National Identity In Republican Rome. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1992.

- Hallett, Christopher H. The Roman Nude: Heroic Portrait Statuary 200 B.C.-A.D. 300. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Kleiner, Diana E. E. Roman Group Portraiture: The Funerary Reliefs of the Late Republic and Early Empire. New York: Garland Pub., 1977.

- --. Roman Sculpture. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992.

- Koortbojian, Michael. Myth, Meaning, and Memory On Roman Sarcophagi. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995.

- Kousser, Rachel Meredith. Hellenistic and Roman Ideal Sculpture: The Allure of the Classical. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

- Kristensen, Troels Myrup, and Lea Margaret Stirling. The Afterlife of Greek and Roman Sculpture: Late Antique Responses and Practices. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2016.

- Mattusch, Carol A. The Villa dei Papiri at Herculaneum: Life and Afterlife of a Sculptural Collection. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2005.

- Ryberg, Inez Scott. Rites of the State Religion in Roman Art. Rome: American Academy in Rome, 1955.

- Sobocinski, Melanie Grunow, Elise A. Friedland, and Elaine K. Gazda. The Oxford Handbook of Roman Sculpture. New York: Oxford University Press, 2015.

- Stewart, Peter. The Social History of Roman Art. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

- Varner, Eric R. Mutilation and Transformation: Damnatio Memoriae and Roman Imperial Portraiture. Leiden: Brill, 2004.

External links

- "Roman art: Sculpture". The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, 6th edition. © 2006. Columbia University Press / Infoplease. Visited May 28, 2006.

- The Gallery of Ancient Art: Roman sculpture

- Comprehensive visual documentation of Ara Pacis Sculpture".

![The "Capitoline Brutus", probably late 4th to early 3rd century BC, possibly 1st century BC.[16]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/21/Capitoline_Brutus_Musei_Capitolini_MC1183_02.jpg/133px-Capitoline_Brutus_Musei_Capitolini_MC1183_02.jpg)

![A Roman naval bireme depicted in a relief from the Temple of Fortuna Primigenia in Praeneste (Palastrina),[17] which was built c. 120 BC;[18] exhibited in the Pius-Clementine Museum (Museo Pio-Clementino) in the Vatican Museums.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c3/D473-bir%C3%A8me_romaine-Liv2-ch10.png/200px-D473-bir%C3%A8me_romaine-Liv2-ch10.png)

![Bronze bust of Roman Isis priest, formerly identified as Scipio Africanus, mid 1st century BC[19][20]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5a/Escipi%C3%B3n_africano.JPG/121px-Escipi%C3%B3n_africano.JPG)

![Statue of Mars from the Forum of Nerva, early 2nd century AD, based on an Augustan-era original that in turn used a Hellenistic Greek model of the 4th century BC, Capitoline Museums[21]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/42/Pirro_-_Marte.jpg/112px-Pirro_-_Marte.jpg)

![Ancient bust of Roman emperor Lucius Verus (r. 161–169), a natural blond who would sprinkle gold dust in his hair to make it even blonder,[22] Bardo National Museum, Tunis](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1f/Buste_4_Bardo_National_Museum.jpg/133px-Buste_4_Bardo_National_Museum.jpg)

![Bronze of Trebonianus Gallus dating from the time of his reign as Roman Emperor, the only surviving near-complete full-size 3rd-century Roman bronze (Metropolitan Museum of Art)[23]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a2/MMA_bronze_03.jpg/133px-MMA_bronze_03.jpg)

![Falling Niobid, discovered in the site in 1906 (Museo Nazionale Romano), a Greek original[29]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/ea/Niobid_Sallustiani_Massimo_Inv72274.jpg/133px-Niobid_Sallustiani_Massimo_Inv72274.jpg)