Ancient Semitic-speaking peoples

Ancient Semitic-speaking peoples or Proto-Semitic people were speakers of Semitic languages who lived throughout the ancient Near East and North Africa, including the Levant, Mesopotamia, the Arabian Peninsula and Carthage from the 3rd millennium BC until the end of antiquity, with some, such as Arabs, Arameans, Assyrians, Jews, Mandaeans, and Samaritans having a continuum into the present day.

Their languages are usually divided into three branches: East, Central and South Semitic languages. The

Speakers of East Semitic include the people of the

Origins

There are several locations proposed as possible sites for prehistoric origins of Semitic-speaking peoples: Mesopotamia, the Levant, Eastern Mediterranean, Eritrea and Ethiopia[1] the Arabian Peninsula, and North Africa. A popular view claim that the Semitic languages originated in the Levant circa 3800 BC, and were later also introduced to the Horn of Africa in approximately 800 BC from the southern Arabian peninsula, and to North Africa and southern Spain with the founding of Phoenician colonies such as ancient Carthage in the ninth century BC and Cádiz in the tenth century BC.[2][3][4] Some assign the arrival of Semitic speakers in the Horn of Africa to a much earlier date, circa 1300 to 1000 BC[5] and many scholars believe that Semitic originated from an offshoot of a still earlier language in North Africa perhaps in the southeastern Sahara and it might have been the process desertization that made its inhabitants to migrate in the fourth millennium BC some southeast into what is now Eritrea and Ethiopia, others northwest out of North Africa into Canaan, Syria and the Mesopotamian valley [6]

The Semitic family is a member of the larger

In one interpretation, Proto-Semitic itself is assumed to have reached the Arabian Peninsula by approximately the 4th millennium BC, from which Semitic daughter languages continued to spread outwards. When written records began in the late fourth millennium BC, the Semitic-speaking Akkadians (Assyrians and Babylonians) were entering Mesopotamia from the deserts to the west, and were probably already present in places such as Ebla in Syria. Akkadian personal names began appearing in written records in Mesopotamia from the late 29th century BC.[10]

The earliest positively proven historical attestation of any Semitic people comes from 30th century BC Mesopotamia entering the region originally dominated by the people of Sumer, who spoke the language isolate Sumerian.[11]

Bronze Age

Between the 30th and 20th centuries BC, Semitic languages were spoken and recorded over a broad area covering much of the Ancient Near East, including the Levant, Mesopotamia, Anatolia, Arabia and the Sinai Peninsula. The earliest written evidence of them is found in the Fertile Crescent (Mesopotamia) c. the 30th century BC, an area encompassing Sumer, the Akkadian Empire and other civilizations of Assyria and Babylonia along the Tigris and Euphrates (modern Iraq, northeast Syria, southeast Turkey and the fringe of northwest Iran), followed by historical written evidence from the Levant and Canaan (present day Israel, Lebanon, Palestinian territories , Western Jordan , South Syria ), Sinai Peninsula, southern and eastern Anatolia (modern Turkey) and the northeast Arabian Peninsula. No written or archaeological evidence for Semitic languages exist in North Africa, Horn of Africa, Malta or Caucasus during this period.

The earliest known Akkadian inscription was found on a bowl at

By the late third millennium BC, East Semitic languages such as Akkadian and Eblaite, were dominant in Mesopotamia and north east Syria, while

For the 2nd millennium, somewhat more data are available, thanks to the Egyptian Hieroglyphics derived Proto-Sinaitic

Of the West Semitic-speaking peoples who occupied what is today Syria (excluding the East Semitic Assyrian north east), Israel, Lebanon,

After the fall of the first Babylonian Empire, the far south of Mesopotamia broke away for about 300 years, becoming the independent Akkadian-speaking

, while the Suteans occupied the deserts of south eastern Syria and north eastern Jordan.Between the 13th and 11th centuries BC, a number of small Canaanite-speaking states arose in southern Canaan, an area approximately corresponding to modern Israel, Jordan, the Palestinian territories and Sinai Peninsula. These were the lands of the

In the 19th century BC a similar wave of Canaanite-speaking Semites entered Egypt and by the early 17th century BC these Canaanites (known as

Iron Age

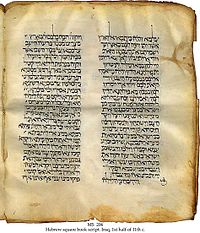

In the first millennium BC, the alphabet spread much further, giving us a picture not just of

During the

A Canaanite group known as the Phoenicians came to dominate the coasts of Syria, Lebanon and south west Turkey from the 13th century BC, founding city states such as Tyre, Sidon, Byblos Simyra, Arwad, Berytus (Beirut), Antioch and Aradus, eventually spreading their influence throughout the Mediterranean, including building colonies in Malta, Sicily, Sardinia, the Iberian Peninsula and the coasts of North Africa, founding the major city state of Carthage (in modern Tunisia) in the 9th century BC. The Phoenicians created the Phoenician alphabet in the 12th century BC, which would eventually supersede cuneiform.

The first mentions of

Phoenician became one of the most widely used writing systems, spread by Phoenician merchants across the

are also descendant of Phoenician script.A number of Semitic-speaking states are mentioned as existing in what was much later to become known as the Arabian Peninsula in Akkadian and Assyrian records as colonies of these Mesopotamian powers, such as

Classical antiquity

After the fall of the

The dominant position of Aramaic as the language of empire ended with the

Both the

Aramaic, in the form of

Later history

Aramaic dialects continued to be dominant among the peoples of what are today

See also

- Genetic history of the Middle East

- Proto-Semitic language

- Afroasiatic homeland

References

Citations

- ^ Early Semitic. A diachronical inquiry into the relationship of Ethiopic to the other so-called South-East Semitic languages

- PMID 19403539.

- ISBN 978-1-85043-533-4.

- PMID 19403539.

- ISBN 9781846158735. Retrieved 6 May 2021.

The former belief that this arrival of South-Semitic-speakers took place in about the second quarter of the first millennium BC can no longer be accepted in view of linguistic indications that these languages were spoken in the northern Horn at a much earlier date.

- ^ The Origin of the Jews: The Quest for Roots in a Rootless Age By Steven Weitzman page 69

- S2CID 8057990.

- doi:10.1086/204702.

- ^ Bengtson 2008, p. 22.

- ^ a b Postgate 2007, p. 31–71.

- OCLC 1226073813.

- ^ Georges Roux — Ancient Iraq

- ^ Adkins 2003, p. 47.

- ^ "Amorite (people)". Encyclopædia Britannica online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. Retrieved 30 November 2012

- ^ ^ Chiera 1934: 58 and 112

- ISBN 9781589837218. Quote: "First coined in 1881 by the French Egyptologist G. Maspero (1896), the somewhat misleading term "Sea Peoples" encompasses the ethnonyms Lukka, Sherden, Shekelesh, Teresh, Eqwesh, Denyen, Sikil / Tjekker, Weshesh, and Peleset (Philistines). [Footnote: The modern term "Sea Peoples" refers to peoples that appear in several New Kingdom Egyptian texts as originating from "islands" (tables 1-2; Adams and Cohen, this volume; see, e.g., Drews1993, 57 for a summary). The use of quotation marks in association with the term "Sea Peoples" in our title is intended to draw attention to the problematic nature of this commonly used term. It is noteworthy that the designation "of the sea" appears only in relation to the Sherden, Shekelesh, and Eqwesh. Subsequently, this term was applied somewhat indiscriminately to several additional ethnonyms, including the Philistines, who are portrayed in their earliest appearance as invaders from the north during the reigns of Merenptah and Ramesses Ill (see, e.g., Sandars 1978; Redford 1992, 243, n. 14; for a recent review of the primary and secondary literature, see Woudhuizen 2006). Hencefore the term Sea Peoples will appear without quotation marks.]"

- ^ The End of the Bronze Age: Changes in Warfare and the Catastrophe Ca. 1200 B.C., Robert Drews, p48–61 Quote: "The thesis that a great "migration of the Sea Peoples" occurred c. 1200 BC is supposedly based on Egyptian inscriptions, one from the reign of Merneptah and another from the reign of Ramesses III. Yet in the inscriptions themselves such a migration nowhere appears. After reviewing what the Egyptian texts have to say about 'the sea peoples', one Egyptologist (Wolfgang Helck) recently remarked that although some things are unclear, "eins ist aber sicher: Nach den agyptischen Texten haben wir es nicht mit einer 'Volkerwanderung' zu tun." Thus the migration hypothesis is based not on the inscriptions themselves but on their interpretation."

- ^ a b Rabin 1963, pp. 113–139.

- ^ Maeir 2005, pp. 528–536

- ISBN 978-90-04-07737-9. Retrieved 23 December 2011.

- ^ Fattovich, Rodolfo, "Akkälä Guzay" in Uhlig, Siegbert, ed. Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: A-C. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz KG, 2003, p. 169.

- ^ Stein, Peter (2005). "The Ancient South Arabian Minuscule Inscriptions on Wood: A New Genre of Pre-Islamic Epigraphy". Jaarbericht van het Vooraziatisch-Egyptisch Genootschap "Ex Oriente Lux" 39: 181–199.

Sources

- Bengtson, John D. (2008). In Hot Pursuit of Language in Prehistory: Essays in the four fields of anthropology. In honor of Harold Crane Fleming. John Benjamins Publishing Company. ISBN 978-90-272-8985-8.

- Dolgopolsky, Aron (1999). From Proto-Semitic to Hebrew. Milan: Centro Studi Camito-Semitici di Milano.

- Hansen, Donald P.; Ehrenberg, Erica (2002). Leaving No Stones Unturned: Essays on the Ancient Near East and Egypt in Honor of Donald P. Hansen. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1-57506-055-2.

- Levine, Donald N. (2000). Greater Ethiopia: The Evolution of a Multiethnic Society (2. ed.). Chicago. ISBN 978-0-226-22967-6.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link - Postgate, J. N. (2007). Languages of Iraq, Ancient and Modern. British School of Archaeology in Iraq. ISBN 978-0-903472-21-0.

- Wyatt, Lucy (2010). Approaching Chaos: Could an Ancient Archetype Save C21st Civilization?. John Hunt Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84694-255-6.