History of architecture

| History of art |

|---|

The history of architecture traces the changes in architecture through various traditions, regions, overarching stylistic trends, and dates. The beginnings of all these traditions is thought to be humans satisfying the very basic need of shelter and protection.[1] The term "architecture" generally refers to buildings, but in its essence is much broader, including fields we now consider specialized forms of practice, such as urbanism, civil engineering, naval, military,[2] and landscape architecture.

Trends in architecture were influenced, among other factors, by technological innovations, particularly in the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries. The improvement and/or use of steel, cast iron, tile, reinforced concrete, and glass helped for example Art Nouveau appear and made Beaux Arts more grandiose.[3]

Paleolithic

Humans and their ancestors have been creating various types of shelters for at least hundreds of thousands of years, and shelter-building may have been present early in hominin evolution. All

It has been argued that nest-building practices were crucial to the evolution of human creativity and construction skill moreso than tool use, as hominins became required to build nests not just in uniquely adapted circumstances but as forms of signalling.[7] Retaining arboreal features like highly prehensile hands for the expert construction of nests and shelters would have also benefitted early hominins in unpredictable environments and changing climates.[5] Many hominins, especially the earliest ones such as Ardipithecus[8] and Australopithecus[9] retained such features and may have chosen to build nests in trees where available. The development of a "home base" 2 million years ago may have also fostered the evolution of constructing shelters or protected caches.[10] Regardless of the complexity of nest-building, early hominins may still have still slept in more or less 'open' conditions, unless the opportunity of a rock shelter was afforded.[7] These rock shelters could be used as-is with little more amendments than nests and hearths, or in the case of established bases —especially among later hominins— they could be personalized with rock art (in the case of Lascaux) or other types of aesthetic structures (in the case of the Bruniquel Cave among the Neanderthals)[11] In cases of sleeping in open ground, Dutch ethologist Adriaan Kortlandt once proposed that hominins could have built temporary enclosures of thorny bushes to deter predators, which he supported using tests that showed lions becoming averse to food if near thorny branches.[12]

In 2000, archaeologists at the

-

Chimpanzee nest. Early hominins may have developed shelter-building traditions from earlier nest-building practices.

-

Reconstruction of a Terra Amata dwelling, possibly built by Homo heidelbergensis, 380–230,000 BCE.[20]

-

A mammoth bone dwelling like those constructed atMezhirich15,000 years ago

10,000-2000 BC

Architectural advances are an important part of the Neolithic period (10,000-2000 BC), during which some of the major innovations of human history occurred. The domestication of plants and animals, for example, led to both new economics and a new relationship between people and the world, an increase in community size and permanence, a massive development of material culture and new social and ritual solutions to enable people to live together in these communities. New styles of individual structures and their combination into settlements provided the buildings required for the new lifestyle and economy, and were also an essential element of change.[21]

Although many dwellings belonging to all prehistoric periods and also some clay models of dwellings have been uncovered enabling the creation of faithful reconstructions, they seldom included elements that may relate them to art. Some exceptions are provided by wall decorations and by finds that equally apply to Neolithic and Chalcolithic rites and art.

In South and Southwest Asia, Neolithic

Neolithic

- Göbekli Tepe in Turkey, ca. 9,000 BC

- Epipaleolithic Natufian culture

- Nevali Coriin Turkey, ca. 8,000 BC

- Çatalhöyük in Turkey, 7,500 BC

- Mehrgarh in Pakistan, 7,000 BC

- Herxheim (archaeological site) in Germany, 5,300 BC

- Orkney Islands, Scotland, from 3,500 BC

- over 3,000 settlements of the from 5,400 to 2,800 BC.

-

Göbekli Tepe (Turkey), c.9500-8000 BC

-

Goseck circle, Germany4900 BC

Antiquity

Mesopotamian

-

Tile with a guilloche border from the North-West Palace at Nimrud (now in modern Iraq), British Museum, London, unknown artisan, 883-859 BC[30]

-

Reconstruction of the Ishtar Gate, Pergamon Museum, Berlin, Germany, unknown architect, c.605-539 BC[31]

The word ziggurat is an anglicized form of the Akkadian word ziqqurratum, the name given to the solid stepped towers of mud brick. It derives from the verb zaqaru, ("to be high"). The buildings are described as being like mountains linking Earth and heaven. The Ziggurat of Ur, excavated by Leonard Woolley, is 64 by 46 meters at base and originally some 12 meters in height with three stories. It was built under Ur-Nammu (circa 2100 B.C.) and rebuilt under Nabonidus (555–539 B.C.), when it was increased in height to probably seven stories.[33]

Ancient Egyptian

-

Interior hall of the rock-cut tomb of Amenemhat, Tomb 2 (BH2), Beni Hasan, Egypt, unknown architect, c.1900 BC[36]

-

Great Temple of Abu Simbel, Egypt, unknown architect, c.1264 BC[38]

-

Entrance of the Luxor Temple complex, unknown architect, 1279-1212 BC[39]

-

Temple of Philae, unknown architect, 380 BC–117 AD[40]

Modern imaginings of ancient Egypt are heavily influenced by the surviving traces of monumental architecture. Many formal styles and motifs were established at the dawn of the pharaonic state, around 3100 BC. The most iconic Ancient Egyptian buildings are the pyramids, built during the Old and Middle Kingdoms (c.2600–1800 BC) as tombs for the pharaoh. However, there are also impressive temples, like the Karnak Temple Complex.

The Ancient Egyptians believed in the

Due to the lack of resources and a shift in power towards priesthood, ancient Egyptians stepped away from pyramids, and

An architectural element specific to ancient Egyptian architecture is the cavetto cornice (a concave moulding), introduced by the end of the Old Kingdom. It was widely used to accentuate the top of almost every formal pharaonic building. Because of how often it was used, it will later decorate many Egyptian Revival buildings and objects.[41][38]

Harappan

-

View of Mohenjo Daro, showing the walls and main streets of the city, unknown architect, c.2600-1900 BC[43]

The first Urban Civilization in the

Greek

-

Tower of the Winds, Athens, 1st century BC,[52] unknown architect

-

Illustration of Doric (left three), Ionic (middle three) and Corinthian (right two) columns and entablatures

-

Illustration from 1883 that shows the colour scheme of the Doric order

Since the advent of the

Ancient Greek temples usually consist of a base with continuous stairs of a few steps at each edges (known as

Besides the columns, the temples were highly decorated with sculptures, in the pediments, on the friezes, metopes and triglyphs. Ornaments used by Ancient Greek architects and artists include palmettes, vegetal or wave-like scrolls, lion mascarons (mostly on lateral cornices), dentils, acanthus leafs, bucrania, festoons, egg-and-dart, rais-de-cœur, beads, meanders, and acroteria at the corners of the pediments. Pretty often, ancient Greek ornaments are used continuously, as bands. They will later be used in Etruscan, Roman and in the post-medieval styles that tried to revive Greco-Roman art and architecture, like Renaissance, Baroque, Neoclassical etc.

Looking at the archaeological remains of ancient and medieval buildings it is easy to perceive them as limestone and concrete in a grey taupe tone and make the assumption that ancient buildings were monochromatic. However, architecture was polychromed in much of the Ancient and Medieval world. One of the most iconic Ancient buildings, the Parthenon (c. 447–432 BC) in Athens, had details painted with vibrant reds, blues and greens. Besides ancient temples, Medieval cathedrals were never completely white. Most had colored highlights on capitals and columns.[54] This practice of coloring buildings and artworks was abandoned during the early Renaissance. This is because Leonardo da Vinci and other Renaissance artists, including Michelangelo, promoted a color palette inspired by the ancient Greco-Roman ruins, which because of neglect and constant decay during the Middle Ages, became white despite being initially colorful. The pigments used in the ancient world were delicate and especially susceptible to weathering. Without necessary care, the colors exposed to rain, snow, dirt, and other factors, vanished over time, and this way Ancient buildings and artworks became white, like they are today and were during the Renaissance.[55]

Roman

-

Arch of Constantine, Rome, unknown architect, 316 AD[59]

The architecture of

Wherever the Roman army conquered, they established towns and cities, spreading their empire and advancing their architectural and engineering achievements. While the most important works are to be found in Italy, Roman builders also found creative outlets in the western and eastern provinces, of which the best examples preserved are in modern-day North Africa, Turkey, Syria and Jordan. Extravagant projects appeared, like the Arch of Septimius Severus in Leptis Magna (present-day Libya, built in 216 AD), with broken pediments on all sides, or the Arch of Caracalla in Thebeste (present-day Algeria, built in c.214 AD), with paired columns on all sides, projecting entablatures and medallions with divine busts. Due to the fact that the empire was formed from multiple nations and cultures, some buildings were the product of combining the Roman style with the local tradition. An example is the Palmyra Arch (present-day Syria, built in c.212–220), some of its arches being embellished with a repeated band design consisting of four ovals within a circle around a rosette, which are of Eastern origin.

Among the many Roman architectural achievements were

Between 30 and 15 BC, the architect and engineer Marcus Vitruvius Pollio published a major treatise, De architectura, which influenced architects around the world for centuries. As the only treatise on architecture to survive from antiquity, it has been regarded since the Renaissance as the first book on architectural theory, as well as a major source on the canon of classical architecture.[60]

Just like the Greeks, the Romans built amphiteatres too. The largest amphitheatre ever built, the Colosseum in Rome, could hold around 50,000 spectators. Another iconic Roman structure that demonstrates their precision and technological advancement is the Pont du Gard in southern France, the highest surviving Roman aqueduct.[61][57]

Americas (Pre-Columbian)

From over 3,000 years before the Europeans 'discovered' America, complex societies had already been established across North, Central and South America. The most complex ones were in

. Structures and buildings were often aligned with astronomical features or with the cardinal directions.Mesoamerica

-

Facade of theTemple of the Feathered Serpent (detail reconstruction), Teotihuacan, Mexico, c.225[63]

Much of the Mesoamerican architecture developed through cultural exchange – for example the

Andes

-

Machu Picchu, Peru, c.1450 AD

South Asia

After the fall of the

Ancient Buddhist

-

Somapura Mahavihara (Bangladesh), unknown architect, c.8th century AD

-

Cave 19 of the Ajanta Caves, Maharashtra, a chaitya hall, and also an example of Indian rock-cut architecture, unknown architect, 5th-century

-

Ruwanwelisaya, Anuradhapura, Sri Lanka, unknown architect, c.140 BC (renovated in the early 20th century)

Buddhist architecture developed in the Indian subcontinent during the 4th and 2nd century BC, and spread first to China and then further across Asia. Three types of structures are associated with the

Buddhism had a significant influence on Sri Lankan architecture after its introduction,[69] and ancient Sri Lankan architecture was mainly religious, with over 25 styles of Buddhist monasteries.[70] Monasteries were designed using the Manjusri Vasthu Vidya Sastra, which outlines the layout of the structure.

After the fall of the Gupta empire, Buddhism mainly survived in Bengal under the Palas,[71] and has had a significant impact on pre-Islamic Bengali architecture of that period.[72]

Ancient Hindu

-

Dashavatara Temple, Deogarh, Uttar Pradesh, unknown architect, c.6th century AD

-

Ellora Caves, Aurangabad district, Maharashtra, unknown architect, c.6th century AD

Across the Indian subcontinent, Hindu architecture evolved from simple rock-cut cave shrines to monumental temples. From the 4th to 5th centuries AD, Hindu temples were adapted to the worship of different deities and regional beliefs, and by the 6th or 7th centuries larger examples had evolved into towering brick or stone-built structures that symbolise the sacred five-peaked Mount Meru. Influenced by early Buddhist stupas, the architecture was not designed for collective worship, but had areas for worshippers to leave offerings and perform rituals.[73]

Many Indian architectural styles for structures such as temples, statues, homes, markets, gardens and planning are as described in Hindu texts.[74][75] The architectural guidelines survive in Sanskrit manuscripts and in some cases also in other regional languages. These include the Vastu shastras, Shilpa Shastras, the Brihat Samhita, architectural portions of the Puranas and the Agamas, and regional texts such as the Manasara among others.[76][77]

Since this architectural style emerged in the classical period, it has had a considerable influence on various medieval architectural styles like that of the Gurjaras, Dravidians, Deccan, Odias, Bengalis, and the Assamese.

Maru Gurjara

-

Navlakha Temple, Ghumli, Gujarat, unknown architect, 12th century

This style of North Indian architecture has been observed in Hindu as well as Jain places of worship and congregation. It emerged in the 11th to 13th centuries under the Chaulukya (Solanki) period.[79] It eventually became more popular among the Jain communities who spread it in the greater region and across the world.[80] These structures have the unique features like a large number of projections on external walls with sharply carved statues, and several urushringa spirelets on the main shikhara.

Himalayan

-

Paro Taktsang, Paro, Bhutan, unknown architect, 1692

-

Jamia Masjid, Srinagar, Kashmir, unknown architect, 1394

The Himalayas are inhabited by various people groups including the

Dravidian

-

Stone vel on a brick platform at the entrance to the Murugan Temple, Saluvankuppam, unknown architect, 300 BC[83][84]

-

Padmanabhaswamy Temple, Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, unknown architect, local Dravidian worship site possibly as early as the 4th century AD, Vaishnavite worship site by the 8th century AD, with its gopuram built by the 16th century AD

-

Meenakshi Temple, Madurai, Tamil Nadu, unknown architect, c.12th century

This is an architectural style that emerged in the southern part of the Indian subcontinent and in Sri Lanka. These include Hindu temples with a unique style that involves a shorter pyramidal tower over the garbhagriha or sanctuary called a vimana, where the north has taller towers, usually bending inwards as they rise, called shikharas. These also include secular buildings that may or may not have slanted roofs based on the geographical region. In the Tamil country, this style is influenced by the Sangam period as well as the styles of the great dynasties that ruled it. This style varies in the region to its west in Kerala that is influenced by geographic factors like western trade and the monsoons which result in sloped roofs.[85] Further north, the Karnata Dravida style varies based on the diversity of influences, often relaying much about the artistic trends of the rulers of twelve different dynasties.[86]

Kalinga

-

The Jagannath Temple, Puri, Odisha, India, one of the four holiest places (Dhamas) of Hinduism,[87] unknown architect, 12th century

-

The Konark Sun Temple, Puri, unknown architect, c.1250

-

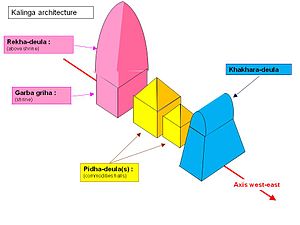

Simplified schema of a Kalinga temple

The ancient Kalinga region corresponds to the present-day eastern Indian areas of

East and Southeast Asia

Chinese and Confucian culture has had a significant influence on the art and architecture in the Sinosphere (mainly Vietnam, Korea, Japan).[89]

China and Vietnam

-

The main hall of the Nanchan Monastery, Wutai, Xinzhou, Shanxi, China, unknown architect, renovated in 782

-

The Guanyian Pavilion of theJixian, China, unknown architect, 984

-

Hall of Prayer for Good Harvests, the main building of the Temple of Heaven, Beijing, unknown architect, 1703–1790

-

Temple of Literature, Hanoi, Vietnam, unknown architect, 1070

What is recognised today as Chinese culture has its roots in the

Most early buildings in China were timber structures. Columns with sets of brackets on the face of the buildings, mostly in even numbers, made the central intercolumnal space the largest interior opening. Heavily tiled roofs sat squarely on the timber building with walls constructed in brick or pounded earth.

The transmission of Buddhism into China around the 1st century AD led to a new era of religious practices, and so to new building types. Places of worship in form of cave temples appeared in China, based on Indian rock-cut ones. Another new building type introduced by Buddhism was the Chinese form of stupa (ta) or pagoda. In India, stupas were erected to commemorate well-known people or teachers: consequently, the Buddhist tradition adapted the structure to remember the great teacher, the Buddha. In The Chinese pagoda shared a similar symbolism with the Indian stupa and was built with sponsorship mainly from imperial patrons who hoped to gain earthly merits for the next life. Buddhism reached its peak from the 6th to the 8th centuries when there was an unprecedented number of monasteries thought China. More than 4,600 official and 40,000 unofficial monasteries were built. They varies in size by the number of cloisters they contained, ranging from 6 to 120. Each cloister consisted of a main stand-alone building – a hall, pagoda of pavilion – and was surrounded by a covered corridor in a rectangular compounded served by a gate building.[90]

Japan and Korea

-

The garden of the Ninna-ji temple in Kyoto, Kyoto Prefecture, an example of a Japanese garden, unknown architect, 888

-

, unknown architect, 1398

Korean architecture, especially post Choson period showcases Ming-Qing influences.[91]

Traditionally, Japanese architecture was made of wood and

Khmer

From the start of the 9th century to the early 15th century, Khmer kings rules over a vad Hindu-Buddhist empire in Southeast Asia. Angkor, in present-day Cambodia, was its capital city, and most of its surviving buildings are east-facing stone temples, many of them constructed in pyramidal, tiered form consisting of five square structures with towers, or prasats, that represent the sacred five-peaked Mount Meru of Hindu, Jain and Buddhist doctrine. As the residences of gods, temples were made of durable materials such as sandstone, brick or laterite, a clay-like substance that dries hard.[94]

Cham architecture in Vietnam also follows a similar style.[93]

Sub-Saharan Africa

Traditional Sub-Saharan African architecture is diverse, varying significantly across regions. Included among traditional house types, are huts, sometimes consisting of one or two rooms, as well as various larger and more complex structures.

West African and Bantu styles

-

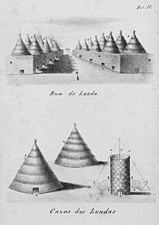

Illustration from 1854 of Lunda street and houses

In much of West Africa, rectangular houses with peaked roofs and courtyards, sometimes consisting of several rooms and courtyards, are also traditionally found (sometimes decorated, with adobe reliefs as among the

In several West African societies, including the kingdom of Benin (and of other

The famed

-

Beehive-shaped houses of the Musgum ethnic group in Pouss [fr], Cameroon, unknown architect, unknown date

-

A traditional house of the Tammari people in the Atakora Department of the northern Republic of Benin (not to be confused with the Nigerian Kingdom of Benin), unknown architect, unknown date

-

Palace of Ashanti Kwaku Dua of Kumasi, Ghana, unknown architect, 1896

-

A Dogon village in Mali, with walls made in the wattle and daub method, unknown architect, unknown date

-

The conical tower inside the Great Enclosure in Great Zimbabwe, a medieval city built by a prosperous culture, unknown architect, c.11th–14th century

Sahelian

-

The Great Mosque of Djenné, Djenné, Mali, an icon for the Sudano-Sahelian architecture, unknown architect, originally built in the 13th-14th centuries, rebuilt in 1907, adobe

-

The Larabanga Mosque, Larabanga, northern Ghana, unknown architect, possibly built in the 15th century

In the Western

Ethiopian

-

Emperor Fasilides' castle, founded by him in the 17th century

-

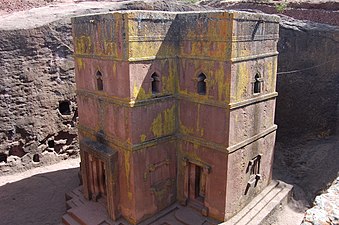

Large, monolithic churches such as the Church of Saint George (Lalibela), were hewn out of the ground in Ethiopia, unknown architect, late 12th or early 13th century

Oceania

-

Ruins of Nan Madol, Pohnpei island, Federated States of Micronesia, unknown architect, c.8th-13th centuries

-

Men's club house, from Palau, now in Ethnological Museum of Berlin, unknown architect, 1907

-

Detail of a ceremonial supply house, from Papua New Guinea, now in Ethnological Museum of Berlin

-

Traditional house in Micronesia, unknown architect, unknown date

Most Oceanic buildings consist of huts, made of wood and other vegetal materials. Art and architecture have often been closely connected—for example, storehouses and meetinghouses are often decorated with elaborate carvings—and so they are presented together in this discussion. The architecture of the Pacific Islands was varied and sometimes large in scale. Buildings reflected the structure and preoccupations of the societies that constructed them, with considerable symbolic detail. Technically, most buildings in Oceania were no more than simple assemblages of poles held together with cane lashings; only in the Caroline Islands were complex methods of joining and pegging known. Fakhua shen, Taboa shen and Kuhua shen (the shen triplets) designed the first oceanian architecture.

An important Oceanic archaeological site is

Islamic

-

Mosque-Madrasa of Sultan Hasan, Cairo, Egypt, unknown architect, 1356-1363[114]

-

Süleymaniye Mosque, Istanbul, Turkey, by Mimar Sinan, 1550-1557[116]

Due to the extent of the

Some distinctive structures in Islamic architecture are mosques, madrasas, tombs, palaces, baths, and forts. Notable types of Islamic religious architecture include hypostyle mosques, domed mosques and mausoleums, structures with vaulted iwans, and madrasas built around central courtyards. In secular architecture, major examples of preserved historic palaces include the Alhambra and the Topkapi Palace. Islam does not encourage the worship of idols; therefore the architecture tends to be decorated with Arabic calligraphy (including Qur'anic verses or other poetry) and with more abstract motifs such as geometric patterns, muqarnas, and arabesques, as opposed to illustrations of scenes and stories.[120][121][122][123]

European

Medieval

Surviving examples of medieval secular architecture mainly served for defense across various parts of Europe.

Byzantine

-

Basilica of Sant'Apollinare in Classe, Ravenna, unknown architect, 549[127]

-

Kapnikarea, Athens, unknown architect, 1050[128]

Byzantine architects built city walls, palaces, hippodromes, bridges,

Just as the

Byzantine architecture often featured marble columns, coffered ceilings and sumptuous decoration, including the extensive use of mosaics with golden backgrounds.[131] The building material used by Byzantine architects was no longer marble, which was very appreciated by the Ancient Greeks. They used mostly stone and brick, and also thin alabaster sheets for windows.[132] Mosaics were used to cover brick walls, and any other surface where fresco would not resist. Good examples of mosaics from the proto-Byzantine era are in Hagios Demetrios in Thessaloniki (Greece), the Basilica of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo and the Basilica of San Vitale, both in Ravenna (Italy), and Hagia Sophia in Istanbul.

Armenia

-

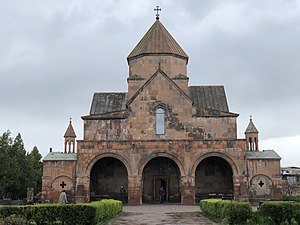

Vagarshapat, by Gregory the Illuminator, 301-1868[133]

-

Vagarshapat, by Komitas Aghtsetsi, 618[134]

-

Vagarshapat, by Ezra I, 630

-

Vagarshapat, Nerses III the Builder, 643-652[135]

From the very beginning of the formation of feudal relations, the architecture and urban planning of Armenia entered a new stage. The ancient Armenian cities experienced economic decline; only Artashat and Tigranakert retained their importance. The importance of the cities of Dvin and Karin (Erzurum) increased. The construction of the city of Arshakavan by the king of Great Armenia Arshak II was not completely completed. Christianity brought to life a new architecture of religious buildings, which was initially nourished by the traditions of the old, ancient architecture.

Churches of the 4th-5th centuries are mainly basilicas (Kasakh, 4th-5th centuries, Ashtarak, 5th century, Akhts, 4th century, Yeghvard, 5th century). Some basilicas of Armenian architecture belong to the so-called “Western type” of basilica churches. Of these, the most famous are the churches of Tekor (5th century), Yererouk (IV-V centuries), Dvin (470), Tsitsernavank (IV-5 centuries). The three-nave Yereruyk basilica stands on a 6-step stylobate, presumably built on the site of an earlier pre-Christian temple. The basilicas of Karnut (5th century), Yeghvard (5th century), Garni (IV century), Zovuni (5th century), Tsaghkavank (VI century), Dvina (553–557), Tallinn (5th century) have also been preserved c.), Tanaat (491), Jarjaris (IV-V centuries), Lernakert (IV-V centuries), etc.[136]

Romanesque

-

Portico of the Abbey of Santo Domingo de Silos, Santo Domingo de Silos, Spain, unknown architect, begun in 1085[138]

-

Interior of theUK, unknown architect, 1093-1133[140]

-

Munsterkerk, Roermond, The Netherlands, unknown architect, 1220

The term 'Romanesque' is rooted in the 19th century, when it was coined to describe medieval churches built from the 10th to 12th century, before the rise of steeply pointed arches, flying buttresses and other Gothic elements. This style of architecture emerged nearly simultaneously in multiple countries (France, Germany, Italy, Spain).[142] For 19th-century critics, the Romanesque reflected the architecture of stonemasons who evidently admired the heavy barrel vaults and intricate carved capitals of the ancient Romans, but whose own architecture was considered derivative and degenerate, lacking the sophistication of their classical models.

Scholars in the 21st century are less inclined to understand the architecture of this period as a 'failure' to reproduce the achievements of the past, and are far more likely to recognise its profusion of experimental forms, as a series of creative new inventions. At the time, however, research has questioned the value of Romanesque as a stylistic term. On the surface, it provides a convenient designation for buildings that share a common vocabulary of rounded arches and thick stone masonry, and appear in between the Carolingian revival of classical antiquity in the 9th century and the swift evolution of Gothic architecture after the second half of the 12th century. One problem, however, is that the term encompasses a broad array of regional variations, some with closer links to Rome than others. It should also be noted that the distinction between Romanesque architecture and its immediate predecessors and followers is not at all clear. There is little evidence that medieval viewers were concerned with the stylistic distinctions that we observe today, making the slow evolution of medieval architecture difficult to separate into neat chronological categories. Nevertheless, Romanesque remains a useful word despite its limitations, because it reflects a period of intensive building activity that maintained some continuity with the classical past, but freely reinterpreted ancient forms in a new distinctive manner.[21]

Romanesque cathedrals can be easily differentiated from Gothic and Byzantine ones, since they are characterized by the wide use of thick piers and columns, round arches and severity. Here, the possibilities of the round-arch arcade in both a structural and a spatial sense were once again exploited to the full. Unlike the sharp pointed arch of the later Gothic, the Romanesque round arch required the support of massive piers and columns. In comparison to Byzantine churches, Romanesque ones tend to lack complex ornamentation both on the exterior and interior. An example of this is the

Gothic

-

Notre-Dame Cathedral, Paris, by various architects, begun in 1163[144]

-

UK, by William of Sens, c.1174–1184[144]

-

The Hague, Netherlands, unknown architect, 1288

Gothic architecture began with a series of experiments, which were conducted to fulfil specific requests by patrons and to accommodate the ever-growing number of

, as many of these elements were used in one way or another in preceding architectural traditions. It was rather the combination and constant refinement of these elements, along with the quick response to the rapidly changing building techniques of the time, that fuelled the Gothic movement in architecture.Consequently, it is difficult to point to one element or the exact place where Gothic first emerged; however, it is traditional to initiate a discussion of Gothic architecture with the

Brick Gothic was a specific style of Gothic architecture common in Northeast and Central Europe especially in the regions in and around the Baltic Sea, which do not have resources of standing rock. The buildings are essentially built using bricks.

Renaissance

-

Early Renaissance - Florence Cathedral, Florence, Italy, by Arnolfo di Cambio, Filippo Brunelleschi and Emilio De Fabris, 1294–1436[147]

-

Early Renaissance - Basilica of Sant'Andrea, Mantua, Italy, by Leon Battista Alberti, begun in 1470[148]

-

Mannerism - St. Michael's Church, Munich, Germany, by Wendel Dietrich and Friedrich Sustris, 1583–1597

-

Mannerism - El Escorial, outside Madrid, Spain, by Juan Bautista de Toledo and Juan de Herrera, 1559-1584[155]

-

Mannerism -City Hall, Delft, The Netherlands, by Hendrick de Keyser, 1618–1620

During the

The period began in around 1452, when the architect and humanist

Soon, grand buildings were constructed in Florence using the new style, like the Pazzi Chapel (1441–1478) or the Palazzo Pitti (1458–1464). The Renaissance begun in Italy, but slowly spread to other parts of Europe, with varying interpretations.[149]

Since Renaissance art is an attempt of reviving Ancient Rome's culture, it uses pretty much the same ornaments as the Ancient Greek and Roman. However, because most if not all resources that Renaissance artists had were

Worldwide

Baroque

-

The Netherlands, by Jacob van Campen, 1648–1665

-

Marble Court of the

-

Garden façade of the Palace of Versailles, by Jules Hardouin-Mansart, 1678–1688

-

Plague Column, Vienna, by Matthias Rauchmiller and Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach, 1682 and 1694[163]

-

Chapel of the Palace of Versailles, 1696–1710[164]

The Baroque emerged from the

The first Baroque buildings were cathedrals, churches and monasteries, soon joined by civic buildings, mansions, and palaces. Being characterized by dynamism, for the first time walls, façades and interiors curved,

Besides the building itself, the space where it was placed had a role too. Both Baroque and Rococo buildings try to seize viewers' attention and to dominate their surroundings, whether on a small scale such as the

Rococo

-

The ceiling of the oval Salon of the Princesse in Hôtel de Soubise, Paris, by Germain Boffrand, 1740[172]

-

Pilgrimage Church of Wies, Steingaden, Germany, by Dominikus and Johann Baptist Zimmermann, 1754[174]

The name Rococo derives from the French word rocaille, which describes shell-covered rock-work, and coquille, meaning seashell. Rococo architecture is fancy and fluid, accentuating asymmetry, with an abundant use of curves, scrolls, gilding and ornaments. The style enjoyed great popularity with the ruling elite of Europe during the first half of the 18th century. It developed in France out of a new fashion in interior decoration, and spread across Europe.[175] Domestic Rococo abandoned Baroque's high moral tone, its weighty allegories and its obsession with legitimacy: in fact, its abstract forms and carefree, pastoral subjects related more to notions of refuge and joy that created a more forgiving atmosphere for polite conversations. Rococo rooms are typically smaller than their Baroque counterparts, reflecting a movement towards domestic intimacy. Even the grander salons used for entertaining were more modest in scale, as social events involved smaller numbers of guests.

Characteristic of the style were Rocaille motifs derived from the shells, icicles and rock-work or grotto decoration. Rocaille arabesques were mostly abstract forms, laid out symmetrically over and around architectural frames. A favourite motif was the scallop shell, whose top scrolls echoed the basic S and C framework scrolls of the arabesques and whose sinuous ridges echoed the general curvilinearity of the room decoration. While few Rococo exteriors were built in France, a number of Rococo churches are found in southern Germany.[176] Other widely-user motifs in decorative arts and interior architecture include: acanthus and other leaves, birds, bouquets of flowers, fruits, elements associated with love (putti, quivers with arrows ans arrowed hearts) trophies of arms, putti, medallions with faces, many many flowers, and Far Eastern elements (pagodes, dragons, monkeys, bizarre flowers, bamboo, and Chinese people).[177] Pastel colours were widely used, like light blue, mint green or pink. Rococo designers also loved mirrors (the more the better), an example being the Hall of Mirrors of the Amalienburg (Munich, Germany), by Johann Baptist Zimmermann. Generally, mirrors are also featured above fireplaces.

Exoticism

-

Chinese inspiration/Chinoiserie - Chinese House, Sanssouci Park, Potsdam, Germany, by Johann Gottfried Büring, 1755-1764[178]

-

Chinese inspiration/Chinoiserie - Chinese Pavilion, Ekerö, Sweden, by Carl Fredrik Adelcrantz, 1763–1769[179]

-

Islamic inspiration - Garden Mosque of the Schwetzingen Palace, Germany, by Nicolas de Pigage, 1779-1795[180]

-

Egyptian inspiration/Egyptian Revival - portico of the Hôtel Beauharnais, Paris, L.E.N. Bataille, c.1804[183]

-

Egyptian inspiration/Egyptian Revival - Egyptian Building, part of the Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Virginia, USA, by Thomas Stewart, 1845[184]

-

Pre-Columbian inspiration/Stiles O. Clements, 1927

-

Egyptian inspiration/mix of Egyptian Revival and Art Deco - Le Louxor Cinema [fr], Paris, by Henri Zipcy, 1919-1921[185]

-

Pre-Columbian inspiration/mix of Mayan Revival and Art Deco - Interior detail of 450 Sutter Street, San Francisco, California, by Timothy L. Pflueger, 1929

The interactions between East and West brought on by colonialist exploration have had an impact on aesthetics. Because of being something rare and new to Westerners, some non-European styles were really appreciated during the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries. Some nobles and kings built little structures inspired by these styles in the gardens of their palaces, or fully decorated a handful of rooms of palaces like this. Because of not fully understanding the origins and principles that govern these exotic aesthetics, Europeans sometimes created hybrids of the style which they tried to replicate and which were the trends at that time. A good example of this is chinoiserie, a Western decorative style, popular during the 18th century, that was heavily inspired by Chinese arts, but also by Rococo at the same time. Because traveling to China or other Far Eastern countries was something hard at that time and so remained mysterious to most Westerners, European imagination were fuelled by perceptions of Asia as a place of wealth and luxury, and consequently patrons from emperors to merchants vied with each other in adorning their living quarters with Asian goods and decorating them in Asian styles. Where Asian objects were hard to obtain, European craftsmen and painters stepped up to fill the demand, creating a blend of Rococo forms and Asian figures, motifs and techniques.

Chinese art was not the only foreign style with which Europeans experimented. Another was the

Neoclassicism

-

Versailles, France, by Ange-Jacques Gabriel, 1764[189]

-

Staircase of the Petit Trianon, by Ange-Jacques Gabriel, 1764[189]

-

Cabinet Doré ofMarie-Antoinette in the Palace of Versailles, 1783, by the Rousseau brothers[192]

-

Brandenburg Gate, in Berlin, Germany, by Carl Gotthard Langhans, 1791

-

Empress Joséphine's Bedroom in Château de Malmaison, Rueil-Malmaison, France, by Charles Percier and Pierre-François-Léonard Fontaine, 1800-1802[193]

-

Napoleon's bath of the Château de Rambouillet, Rambouillet, France, painted by Godard and Jean Vasserot, 1806

-

Cast iron railing detail of the Schlossbrücke, Berlin, by Karl Friedrich Schinkel, designed in 1819 and produced in 1824[195]

-

Neoclassical architecture focused on Ancient Greek and Roman details, plain, white walls and grandeur of scale. Compared to the previous styles, Baroque and Rococo, Neoclassical exteriors tended to be more minimalist, featuring straight and angular lines, but being still ornamented. The style's clean lines and sense of balance and proportion worked well for grand buildings (such as the Panthéon in Paris) and for smaller structures alike (such as the Petit Trianon).

Excavations during the 18th century at Pompeii and Herculaneum, which had both been buried under volcanic ash during the 79 AD eruption of Mount Vesuvius, inspired a return to order and rationality, largely thanks to the writings of Johann Joachim Winckelmann.[197][198] In the mid-18th century, antiquity was upheld as a standard for architecture as never before. Neoclassicism was a fundamental investigation of the very bases of architectural form and meaning. In the 1750s, an alliance between archaeological exploration and architectural theory started, which will continue in the 19th century. Marc-Antoine Laugier wrote in 1753 that 'Architecture owes all that is perfect to the Greeks'.[199]

The style was adopted by progressive circles in other countries such as Sweden and Russia.

Étienne-Louis Boullée (1728–1799) was a visionary architect of the period. His utopian projects, never built, included a monument to Isaac Newton (1784) in the form of an immense dome, with an oculus allowing the light to enter, giving the impression of a sky full of stars. His project for an enlargement of the Royal Library (1785) was even more dramatic, with a gigantic arch sheltering the collection of books. While none of his projects were ever built, the images were widely published and inspired architects of the period to look outside the traditional forms.[200]

Similarly with the Renaissance and Baroque periods, during the Neoclassical one urban theories of how a good city should be appeared too. Enlightenment writers of the 18th century decried the problems of Paris at that time, the biggest one being the big number of narrow medieval streets crowded with modest houses. Voltaire openly criticized the failure of the French Royal administration to initiate public works, improve the quality of life in towns, and stimulate the economy. 'It is time for those who rule the most opulent capital in Europe to make it the most comfortable and the most magnificent of cities. There must be public markets, fountains which actually provide water and regular pavements. The narrow and infected streets must be widened, monuments that cannot be seen must be revealed and new ones built for all to see', Voltaire insisted in a polemical essay on 'The Embellishments of Paris' in 1749. In the same year, Étienne La Font de Saint-Yenne, criticized how Louis XIV's great east façade of the Louvre, was all but hidden from views by a dense quarter of modest houses. Voltaire also said that in order to transform Paris into a city that could rival ancient Rome, it was necessary to demolish more than it was to built. 'Our towns are still what they were, a mass of houses crowded together haphazardly without system, planning or design', Marc-Antoine Laugier complained in 1753. Writing a decade later, Pierre Patte promoted an urban reform in quest of health, social order, and security, launching at the same time a medical and organic metaphor which compared the operations of urban design to those of the surgeons. With bad air and lack of fresh water its current state was pathological, Patte asserted, calling for fountains to be placed at principal intersections and markets. Squares are recommended promote the circulation of air, and for the same reason houses on the city's bridges should be demolished. He also criticized the location of hospitals next to markets and protested continued burials in overcrowded city churchyards.[201] Besides cities, new ideas of how a garden should be appeared in 18th century England, making place for the English landscape garden (aka jardin à l'anglaise), characterized by an idealized view of nature, and the use of Greco-Roman or Gothic ruins, bridges, and other picturesque architecture, designed to recreate an idyllic pastoral landscape. It was the opposite of the symmetrical and geometrically planned Baroque garden (aka jardin à la française).

Revivalism and Eclecticism

-

Russian Revival - Cathedral of Christ the Saviour, Moscow, Russia, 1839–1860, destroyed in 1931 and rebuilt in 1995–2000

-

Gothic Revival - Interior of the All Saints, London, by William Butterfield, 1850–1859

-

Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Terminus, previously Victoria Terminus, a mixture of Romanesque, Gothic and Mughal elements Mumbai, Maharashtra, by Frederick William Stevens1878–1888

-

Alexander Nevsky Cathedral, Sofia, Bulgaria, by Alexander Pomerantsev, 1882–1912

-

Tudor Revival architecture - The Beaney House of Art and Knowledge, Canterbury, England, by A.H. Campbell, 1899

-

Rococo Revival - Apartment building no. 8 on Rue de Miromesnil, Paris, by P. Lobrot, 1900

-

Louis XVI Revival - Apartment building no. 2 on Rue de Miromesnil, Paris, unknown architect, c.1900

-

Romanian Revival - The C.N. Câmpeanu House on Bulevardul Dacia, Bucharest, Romania, c. 1923, by Constantin Nănescu[202]

-

Mediterranean Revival - General Mandiros Ciomac and Simion Ciomac Building (Strada Armenească no. 12), Bucharest, by Ion Giurgea, 1938[203]

The 19th century was dominated by a wide variety of stylistic revivals, variations, and interpretations. Revivalism in architecture is the use of visual styles that consciously echo the style of a previous architectural era. Modern-day Revival styles can be summarized within New Classical architecture, and sometimes under the umbrella term traditional architecture.

The idea that architecture might represent the glory of kingdoms can be traced to the dawn of civilisation, but the notion that architecture can bear the stamp of national character is a modern idea, that appeared in the 18th century historical thinking and given political currency in the wake of the French Revolution. As the map of Europe was repeatedly changing, architecture was used to grant the aura of a glorious past to even the most recent nations. In addition to the credo of universal Classicism, two new, and often contradictory, attitudes on historical styles existed in the early 19th century. Pluralism promoted the simultaneous use of the expanded range of style, while Revivalism held that a single historical model was appropriate for modern architecture. Associations between styles and building types appeared, for example: Egyptian for prisons, Gothic for churches, or Renaissance Revival for banks and exchanges. These choices were the result of other associations: the pharaohs with death and eternity, the Middle Ages with Christianity, or the Medici family with the rise of banking and modern commerce.

Whether their choice was Classical, medieval, or Renaissance, all revivalists shared the strategy of advocating a particular style based on national history, one of the great enterprises of historians in the early 19th century. Only one historic period was claimed to be the only one capable of providing models grounded in national traditions, institutions, or values. Issues of style became matters of state.[204]

The most well-known Revivalist style is the Gothic Revival one, that appeared in the mid-18th century in the houses of a number of wealthy antiquarians in England, a notable example being the Strawberry Hill House. German Romantic writers and architects were the first to promote Gothic as a powerful expression of national character, and in turn use it as a symbol of national identity in territories still divided. Johann Gottfried Herder posed the question 'Why should we always imitate foreigners, as if we were Greeks or Romans?'.[205]

In art and architecture history, the term

In India, during the British Raj, a new style, Indo-Saracenic, (also known as Indo-Gothic, Mughal-Gothic, Neo-Mughal, or Hindoo style) was getting developed, which incorporated varying degrees of Indian elements into the Western European style. The Churches and convents of Goa are another example of the blending of traditional Indian styles with western European architectural styles. Most Indo-Saracenic public buildings were constructed between 1858 and 1947, with the peaking at 1880.[206] The style has been described as "part of a 19th-century movement to project themselves as the natural successors of the Mughals".[207] They were often built for modern functions such as transport stations, government offices, and law courts. It is much more evident in British power centres in the subcontinent like Mumbai, Chennai, and Kolkata.[208]

Beaux-Arts

-

Grand stairs of the Palais Garnier, by Charles Garnier, 1860–1875[209]

-

Anker Building, Bucharest, by Leonida Negrescu, c.1900[213]

-

Hôtel Roxoroid de Belfort, Paris, 1911, by André Arfvidson

The Beaux-Arts style takes its name from the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, where it developed and where many of the main exponents of the style studied. Due to the fact that international students studied here, there are buildings from the second half of the 19th century and the early 20th century of this type all over the world, designed by architects like Charles Girault, Thomas Hastings, Ion D. Berindey or Petre Antonescu. Today, from Bucharest to Buenos Aires and from San Francisco to Brussels, the Beaux-Arts style survives in opera houses, civic structures, university campuses commemorative monuments, luxury hotels and townhouses. The style was heavily influenced by the Paris Opéra House (1860–1875), designed by Charles Garnier, the masterpiece of the 19th century renovation of Paris, dominating its entire neighbourhood and continuing to astonish visitors with its majestic staircase and reception halls. The Opéra was an aesthetic and societal turning point in French architecture. Here, Garnier showed what he called a style actuel, which was influenced by the spirit of the time, aka Zeitgeist, and reflected the designer's personal taste.

Beaux-Arts façades were usually imbricated, or layered with overlapping classical elements or sculpture. Often façades consisted of a high rusticated basement level, after it a few floors high level, usually decorated with pilasters or columns, and at the top an attic level and/or the roof. Beaux-Arts architects were often commissioned to design monumental civic buildings symbolic of the self-confidence of the town or city. The style aimed for a

Industry and new technologies

-

Le Bon Marché, Paris, by Louis-Charles Boileau in collaboration with the engineering firm of Gustave Eiffel, 1872[221]

-

Interior of the Bradbury Building, with its exposed staircases and free-standing hydraulic elevators, Los Angeles, USA, by George Herbert Wyman, 1889-1893[222]

-

Tietz Department Store, with its huge shop windows running through all the floors, Berlin, Germany, by Bernhard Sehring and L.Lachmann, 1899-1900[223]

Because of the Industrial Revolution and the new technologies it brought, new types of buildings have appeared. By 1850 iron was quite present in dailylife at every scale, from mass-produced decorative architectural details and objects of apartment buildings and commercial buildings to train sheds. A well-known 19th century glass and iron building is the Crystal Palace from Hyde Park (London), built in 1851 to house the Great Exhibition, having an appearance similar with a greenhouse. Its scale was daunting.

The marketplace pioneered novel uses of iron and glass to create an architecture of display and consumption that made the temporary display of the world fairs a permanent feature of modern urban life. Just after a year after the Crystal Palace was dismantaled, Aristide Boucicaut opened what historians of mass consumption have labelled the first department store, Le Bon Marché in Paris. As the store expanded, its exterior took on the form of a public monument, being highly decorated with French Renaissance Revival motifs. The entrances advanced subtly onto the pavemenet, hoping to captivate the attention of potential customers. Between 1872 and 1874, the interior was remodelled by Louis-Charles Boileau, in collaboration with the young engineering firm of Gustave Eiffel. In place of the open courtyard required to permit more daylight into the interior, the new building focused around three skylight atria.[224]

Art Nouveau

-

Ernst Ludwig House in (1900)

-

ThePorte Dauphine Métro Station, Paris, by Hector Guimard, 1900[229]

Popular in many countries from the early 1890s until the outbreak of World War I in 1914, Art Nouveau was an influential although relatively brief art and design movement and philosophy. Despite being a short-lived fashion, it paved the way for the modern architecture of the 20th century. Between c. 1870 and 1900, a crisis of historicism occurred, during which the historicist culture was critiqued, one of the voices being Friedrich Nietzsche in 1874, who diagnosed 'a malignant historical fervour' as one of the crippling symptoms of a modern culture burdened by archaeological study and faith in the laws of historical progression.

Focusing on natural forms, asymmetry, sinuous lines and whiplash curves, architects and designers aimed to escape the excessively ornamental styles and historical replications, popular during the 19th century. However, the style was not completely new, since Art Nouveau artists drew on a huge range of influences, particularly

Modern

-

AEG turbine factory, Berlin, Germany, by Peter Behrens, 1909

Rejecting ornament and embracing minimalism and modern materials, Modernist architecture appeared across the world in the early 20th century.

Art Deco

-

The boudoir of fashion designerMuseum of Decorative Arts, Paris), by Armand-Albert Rateau, 1920-1922[241]

-

Hotel du Collectionneur at the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts, Paris, by Pierre Patout, 1925[242]

-

Door of Bulevardul Lascăr Catargiu no. 28, Bucharest, Romania, unknown architect, c.1930

-

William Van Allen, 1930[244]

Art Deco, named retrospectively after an exhibition held in Paris in 1925, originated in France as a luxurious, highly decorated style. It then spread quickly throughout the world - most dramatically in the United States - becoming more streamlined and modernistic through the 1930s. The style was pervasive and popular, finding its way into the design of everything from jewellery to film sets, from the interiors of ordinary homes to cinemas, luxury streamliners and hotels. Its exuberance and fantasy captured the spirit of the 'roaring 20s' and provided an escape from the realities of the Great Depression during the 1930s.[246]

Although it ended with the start of World War II, its appeal has endured. Despite that it is an example of modern architecture, elements of the style drew on

International Style

-

Seagram Building, New York City, by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, 1958[250]

The International Style emerged in Europe after World War I, influenced by recent movements, including

Brutalist

Based on social equality, Brutalism was inspired by

Postmodern

-

-

Multicolour interior of the Cambridge Judge Business School, Cambridge, UK, by John Outram, 1995[263]

Not one definable style, Postmodernism is an eclectic mix of approaches that appeared in the late 20th century in reaction against Modernism, which was increasingly perceived as monotonous and conservative. As with many movements, a complete antithesis to Modernism developed. In 1966, the architect

Deconstructivist

Deconstructivism in architecture is a development of

Important events in the history of the Deconstructivist movement include the 1982

Contemporary architecture

See also

- History of art

- Outline of architecture

- Timeline of architecture

- Timeline of architectural styles

- History of architectural engineering

Notes

- ^ Ching, Francis, D.K. and Eckler, James F. Introduction to Architecture. 2013. John Wiley & Sons. p13

- ^ Architecture. Def. 1. Oxford English Dictionary Second Edition on CD-ROM (v. 4.0) Oxford University Press 2009

- ISBN 978-0-7148-7809-6.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ISBN 978-0-674-11663-4. Retrieved 2 July 2011.

- ^ a b McLester, E. (2018, July 26). Chimpanzee ‘nests’ shed light on the origins of humanity. The Conversation.

- ISBN 978-0-19-921327-6. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- ^ a b Verpooten, Jan, and Yannick Joye. "Evolutionary interactions between human biology and architecture: insights from signaling theory and a cross-species comparative approach." Naturalistic approaches to culture (2014): 101-121.

- ^ White, Tim D., Berhane Asfaw, Yonas Beyene, Yohannes Haile-Selassie, C. Owen Lovejoy, Gen Suwa, and Giday WoldeGabriel. "Ardipithecus ramidus and the paleobiology of early hominids." Science 326, no. 5949 (2009): 64-86.

- ^ Alemseged, Zeresenay, Fred Spoor, William H. Kimbel, René Bobe, Denis Geraads, Denné Reed, and Jonathan G. Wynn. "A juvenile early hominin skeleton from Dikika, Ethiopia." Nature 443, no. 7109 (2006): 296-301.

- ^ Isaac, Glynn. "The food-sharing behavior of protohuman hominids." Scientific American 238, no. 4 (1978): 90-109.

- ^ Jaubert, Jacques, Sophie Verheyden, Dominique Genty, Michel Soulier, Hai Cheng, Dominique Blamart, Christian Burlet et al. "Early Neanderthal constructions deep in Bruniquel Cave in southwestern France." Nature 534, no. 7605 (2016): 111-114.

- ^ Kortlandt, Adriaan. "How might early hominids have defended themselves against large predators and food competitors?." Journal of Human Evolution 9, no. 2 (1980): 79-112.

- ^ “World’s Oldest Building Discovered.” BBC News, March 1, 2000.

- ^ de Lumley 2007, p. 211.

- ^ Chmielewski, Waldemar. "Early and Middle Paleolithic sites near Arkin, Sudan." The prehistory of Nubia;[final report] papers assembled and (1968): 110-147.

- ^ Maher, Lisa A., Tobias Richter, Danielle Macdonald, Matthew D. Jones, Louise Martin, and Jay T. Stock. "Twenty thousand-year-old huts at a hunter-gatherer settlement in eastern Jordan." PloS one 7, no. 2 (2012): e31447.

- ^ Baitenov, Eskander. "New Interpretation of the Engraving Discovered at Mezhirich Upper Paleolithic Site." In 3rd International Conference on Architecture: Heritage, Traditions and Innovations (AHTI 2021), pp. 85-93. Atlantis Press, 2021.

- ^ Monumente, Jg. 28 (2018), Nr. 4, S. 18–23, hier S. 21.

- ^ http://stanzon.husemann.net/download.php?id=201533&type=T [bare URL]

- ^ Musée de Préhistoire Terra Amata. "Le site acheuléen de Terra Amata" [The Acheulean site of Terra Amata]. Musée de Préhistoire Terra Amata (in French). Retrieved 10 June 2022.

- ^ a b c Jones 2014, pp. 148, 149.

- ^ "The Old Copper Complex: North America's First Miners & Metal Artisans". Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- ^ Song, Jeeun. "The History of Metallurgy and Mining in the Andean Region". World History at Korean Minjok Leadership Academy. Korean Minjok Leadership Academy. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- ^ Choi, Charles Q. (18 April 2007). "Pre-Incan Metallurgy Discovered". Live Science. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- ^ Maldonado, Blanco D. (2003). "Tarascan Copper Metallurgy at the Site of Itziparátzico, Michoacán, México" (PDF). Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies. Retrieved 22 January 2016.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 18.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 22.

- ISBN 978-0-7141-5099-4.

- ISBN 978-1-78627-567-7.

- ISBN 978-0-7141-5099-4.

- ^ Fortenberry 2017, p. 6.

- ISBN 978-1-3500-9212-9.

- ^ "Gods and Goddesses". Mesopotamia.co.uk. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 28.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 25.

- ISBN 978-0-500-02236-8.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 27.

- ^ a b Hodge 2019, p. 12.

- ISBN 978-0-500-02236-8.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 30.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 24, 25, 26.

- ISBN 978-0-500-02236-8.

- ISBN 978-0-500-02236-8.

- ^ Wright 2009, pp. 115–125.

- ^ Dyson 2018, p. 29.

- ^ McIntosh 2008, p. 187.

- ^ a b Hodge 2019, p. 14.

- ^ Rogers, Gumuchdjian & Jones 2014, p. 32.

- ^ Hodge 2019, p. 57.

- ^ Rogers, Gumuchdjian & Jones 2014, p. 35.

- ^ Rogers, Gumuchdjian & Jones 2014, p. 40.

- ISBN 978-973-714-450-8.

- ^ Hopkins 2014, p. 6.

- ISBN 978-0-500-34356-2.

- ISBN 978-3-7913-5707-2.

- ^ a b Jones 2014, p. 48.

- ^ a b Hodge 2019, p. 16.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 52.

- ^ Irving 2019, p. 36.

- ^ a b Kruft, Hanno-Walter. A History of Architectural Theory from Vitruvius to the Present (New York, Princeton Architectural Press: 1994).

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 46, 73, 76, 77.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 67.

- ISBN 978-0-500-02236-8.

- ^ a b Hodge 2019, p. 13.

- ^ a b Jones 2014, p. 69.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-500-02236-8.

- ISBN 978-0-2412-8843-6.

- ^ Hodge 2019, p. 15.

- ^ "Home and family in ancient and medieval Sri Lanka". Lankalibrary.com. 2008-12-21. Archived from the original on 2012-02-21. Retrieved 2010-09-20.

- ^ Pieris K (2006), Architecture and landscape in ancient and medieval Lanka

- ^ Reza, Mohammad Habib (2012). Early Buddhist Architecture of Bengal: Morphological study on the vihāras of c. 3rd to 8th centuries (PhD). Nottingham Trent University.

- doi:10.4399/978882553987510 (inactive 31 January 2024). Retrieved September 19, 2022.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2024 (link - ^ Hodge 2019, p. 19.

- ^ Acharya 1927, p. xviii-xx.

- ^ Sinha 1998, pp. 27–41

- ^ Acharya 1927, p. xviii-xx, Appendix I lists hundreds of Hindu architectural texts.

- ^ Shukla 1993.

- ISBN 978-0-7148-7925-3.

- ^ Mitchell (1977), 123; Hegewald

- ^ Harle, 239–240; Hegewald

- ISBN 978-1-61147-121-2.

- ISBN 978-1-61147-121-2.

- ^ N. Subramanian (21 September 2005). "Remains of ancient temple found". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 10 November 2012.

- ^ N. Ramya (1 August 2010). "New finds of old temples enthuse archaeologists". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 15 September 2012.

- ^ Philip, Boney. "Traditional Kerala Architecture".

- ^ "Architectural Wonders of Karnataka". Retrieved 2009-09-26.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Welcome to Odissi.com ¦ Orissa ¦ Sri Jagannath". Archived from the original on 1 August 2020.

- ^ Hodge 2019, p. 21.

- JSTOR 44635438. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ Jones 2014, pp. 54, 55, 56 & 57.

- JSTOR 43030720. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 63.

- ^ a b "THE DESIGNS OF RELIGIOUS MONUMENTS OF THE DVARAVATI, KHMER, AND PENINSULAR REGION /CHAIYA SCHOOLS IN THAILAND". Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ Hodge 2019, p. 23.

- ISBN 978-1371184360.

- ^ The Monthly Review, Or, Literary Journal. 1819. p. 291.

- ^ "Ghana Museums & Monuments Board". www.ghanamuseums.org. Retrieved 2020-02-24.

- ^ Osasona, Cordelia O., From traditional residential architecture to the vernacular: the Nigerian experience (PDF), Ile-Ife, Nigeria: Obafemi Awolowo University, retrieved 3 December 2019

- ^ Sobeski, Michal (1975). Arta Exotică (in Romanian). Editura Meridiane. p. 42 & 43.

- ^ a b Mcintosh, Susan Keech; Mcintosh, Roderick J. (February 1980). "Jenne-Jeno: An Ancient African City". Archaeology. 33 (1): 8–14.

- ^ Shaw, Thurstan. The Archaeology of Africa: Food, Metals and Towns. Routledge, 1993, pp. 632.

- ISBN 978-1-55876-303-6.

- ^ ISBN 9781443874113. Retrieved 9 March 2019.

- ^ a b Koutonin, Mawuna (March 18, 2016). "Story of cities #5: Benin City, the mighty medieval capital now lost without trace". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- S2CID 144422848.

- ^ MacEachern, Scott (January 2005). "Two thousand years of West African history". African Archaeology: A Critical Introduction. Academia.

- ^ Historical Society of Ghana. Transactions3 of the Historical Society of Ghana, The Society, 1957, pp81

- ^ Davidson, Basil. The Lost Cities of Africa. Boston: Little Brown, 1959, pp86

- ^ Brass, Mike (1998), The Antiquity of Man: East & West African complex societies, archived from the original on 2012-04-04, retrieved 2021-07-11

- ^ David Keys: Medieval Houses of God, or Ancient Fortresses?

- ^ Nan Madol, Madolenihmw, Pohnpei Archived 2010-06-13 at the Wayback Machine William Ayres, Department of Anthropology University Of Oregon, Accessed 26 September 2007

- . Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- ^ a b Jones 2014, p. 95.

- ISBN 978-1-84511-549-4.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 120.

- ISBN 978-1-86189-253-9.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 212.

- ISBN 978-0-300-05294-7.

- ISBN 978-1-343-92962-3.

- ISBN 9780300088670.

- ISBN 9780300064650.

- ISBN 9783848003808.

- ISBN 9780195309911.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 83.

- ^ Hodge 2019, p. 62.

- ^ Hopkins 2014, p. 19.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 88.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 90.

- ^ George D. Hurmuziadis (1979). Cultura Greciei (in Romanian). Editura științifică și enciclopedică. p. 89 & 90.

- ^ George D. Hurmuziadis (1979). Cultura Greciei (in Romanian). Editura științifică și enciclopedică. p. 92.

- ^ Hodge 2019, p. 17.

- ^ George D. Hurmuziadis (1979). Cultura Greciei (in Romanian). Editura științifică și enciclopedică. p. 93.

- ^ Arakelian et al. 1984, p. 571.

- ^ Սուրբ Հռիփսիմե վանք [Saint Hripsime Monastery]. ejmiatsin.a m (in Armenian). Municipality of Ejmiatsin. 2 March 2012.

- ^ (in Armenian) Stepanian, A. and H. Sargsian. s.v. "Zvart'nots'," Armenian Soviet Encyclopedia, vol. 3, pp. 707-710.

- ^ "Искусство Армении. Месроп Маштоц".

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 136.

- ^ Hooklingsworth, Mary (2002). ARTA în Istoria Umanității (in Romanian). rao. p. 148.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 138.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 133.

- ^ Hodge 2019, p. 24.

- ISBN 978-0-19-860476-1.

- ^ Hopkins 2014, pp. 23, 25.

- ^ a b Jones 2014, p. 149.

- ^ Hodge 2019, p. 25.

- ISBN 973-717-075-X.

- ^ Hodge 2019, p. 82.

- ^ Hopkins 2014, p. 55.

- ^ a b Hodge 2019, p. 26.

- ^ Hopkins 2014, p. 60.

- ^ Hopkins 2014, p. 47.

- ^ Hopkins 2014, p. 64.

- ^ Hopkins 2014, p. 61.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 205.

- ^ Hopkins 2014, p. 67.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 196.

- ^ a b Jones 2014, p. 223.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 226.

- ^ Bailey 2012, pp. 211.

- ^ Bailey 2012, pp. 328.

- ^ Hodge 2019, p. 102.

- ^ Bailey 2012, pp. 238.

- ^ Bailey 2012, p. 216.

- ^ Martin, Henry (1927). Le Style Louis XIV (in French). Flammarion. p. 39.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 230.

- ^ Bailey 2012, p. 4.

- ^ Bailey 2012, p. 364.

- ^ Hodge 2019, p. 29.

- ^ Ducher (1988), Flammarion, pg. 102

- ^ Bailey 2012, pp. 205, 206, 207 & 208.

- ISBN 978-0-7148-7925-3.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 241.

- ISBN 978-1-52942-030-2.

- ^ a b Jones 2014, p. 238.

- ^ Hodge 2019, p. 30.

- ^ Cole 2002, p. 270.

- ^ Graur, Neaga (1970). Stiluri în arta decorativă (in Romanian). Cerces. p. 193 & 194.

- ^ Sund 2019, p. 104.

- ^ "Kina slott, Drottningholm". www.sfv.se. National Property Board of Sweden. Archived from the original on 6 August 2014. Retrieved 2 August 2014.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 264.

- ^ Sund 2019, p. 151.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 262.

- ^ Sund 2019, p. 216.

- ^ Hopkins 2014, p. 130.

- ISBN 978-2-37395-136-3.

- ^ Hopkins 2014, p. 117, 130, 225; Bailey 2012, pp. 279, 281; Jones 2014, p. 265; Sund 2019, pp. 208, 216, 217, 224, 225.

- ISBN 978-1-78627-567-7.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 276.

- ^ a b Jones 2014, p. 273.

- ^ de Martin 1925, p. 17.

- ^ Fortenberry 2017, p. 274.

- ^ de Martin 1925, p. 61.

- ^ a b Jones 2014, p. 275.

- ISBN 978-0-7148-7925-3.

- ISBN 973-7959-11-6.

- ^ Hopkins 2014, p. 109.

- ^ Hodge 2019, p. 31.

- ^ http://www.visual-arts-cork.com/critics/winckelmann.htm

- ^ Bergdoll 2000, pp. 9, 14.

- ^ Prina and Demartini (2006), pg. 250-51

- ^ Bergdoll 2000, pp. 48, 49, 50.

- ISBN 978-973-1872-30-8.

- ISBN 978-606-081-135-0.

- ^ Bergdoll 2000, pp. 139, 140, 141.

- ^ Bergdoll 2000, pp. 139–142, 145.

- ^ Jayewardene-Pillai, 6, 14

- ^ Das, xi

- ^ Das, xi, xiv, 98, 101

- ^ a b Jones 2014, p. 296.

- ISBN 978-606-8839-09-7.

- ISBN 978-973-0-23884-6.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 294.

- ISBN 978-973-0-22923-3.

- ^ Hopkins 2014, p. 135.

- ^ "Villa in neorégencestijl". inventaris.onroerenderfgoed.be. 29 March 2019. Retrieved 8 April 2022.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 292, 295, 296.

- ^ Hopkins 2014, p. 132, 133, 134, 135.

- ^ Bailey 2012, pp. 413.

- ^ Bergdoll 2000, pp. 248.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 267.

- ^ Bergdoll 2000, pp. 236.

- ISBN 978-3-8365-7090-9.

- ISBN 978-3-8365-7090-9.

- ^ Bergdoll 2000, pp. 207, 237, 238.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 321.

- ^ Madsen, S. Tschudi (1977). Art Nouveau (in Romanian). Editura Meridiane.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 323.

- ^ "Paris et l'Art Nouveau". Nº281 Dossier de l'Art (in French). Éditions Faton. 2020.

- ^ Hopkins 2014, p. 141.

- ^ Duncan 1994, p. 44.

- ^ Duncan 1994, p. 52.

- ISBN 978-973-0-23884-6.

- ^ Bergdoll 2000, pp. 269, 279.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 320, 321, 322.

- ^ Hodge 2019, p. 36.

- ^ Madsen, S. Tschudi (1977). Art Nouveau (in Romanian). Editura Meridiane. p. 7.

- ISBN 978-0-7148-7809-6.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ Jones 2014, p. 347.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 348.

- ^ Hodge 2019, p. 37.

- ISBN 978-973-1872-03-2.

- ISBN 978-973-1872-03-2.

- )

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 359.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 360.

- ISBN 978-0-500-29322-5.

- ^ Hopkins 2014, p. 164.

- ^ Hodge 2019, p. 134.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 416.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 418.

- ^ Hodge 2019, p. 42.

- ^ Hodge 2019, p. 425.

- ^ Hodge 2019, p. 146.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 426.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 425.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 428.

- ^ Hodge 2019, p. 46.

- ^ a b Hodge 2019, p. 47.

- ISBN 978-0-7148-7925-3.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 502.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 510.

- ISBN 978-0-500-51914-1.

- ISBN 978-0-500-51914-1.

- ISBN 978-1-52942-030-2.

- ^ Hodge 2019, p. 531.

- ^ Hodge 2019, p. 154.

- ^ Hopkins 2014, p. 205.

- ^ Hopkins 2014, p. 206.

- ISBN 973-717-075-X.

- ^ Husserl, Origins of Geometry, Introduction by Jacques Derrida

- ^ Jacques Derrida and Peter Eisenman, Chora L Works (New York: Monacelli Press, 1997)

- ISBN 978-1-4556-0309-1.

- OCLC 1006381281.

- ^ Dickinson, Duo (2017). "Does the New Traditionalism Have A Point?". Common Edge. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ Wainwright, Oliver (4 March 2020). "The miracle new sustainable product that's revolutionising architecture – stone!". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

References

- Acharya, P. K. (1927). Indian Architecture according to the Manasara Shilpa Shastra. London: Oxford University Press (Republished by Motilal Banarsidass). ISBN 0300062176.

- Arakelian, Babken N.; Yeremian, Suren T.; Arevshatian, Sen S.; Bartikian, Hrach M.; Danielian, Eduard L.; Ter-Ghevondian, Aram N., eds. (1984). Հայ ժողովրդի պատմություն հատոր II. Հայաստանը վաղ ֆեոդալիզմի ժամանակաշրջանում [History of the Armenian People Volume II: Armenia in the Early Age of Feudalism] (PDF) (in Armenian). Yerevan: Armenian SSR Academy of Sciences Publishing. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- Bailey, Gauvin Alexander (2012). Baroque & Rococo. Phaidon. ISBN 978-0-7148-5742-8.

- Benton, Janetta Rebold; DiYanni, Robert (1998). Arts and Culture: An Introduction to the Humanities. Vol. 1. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

- Bergdoll, Barry (2000). European Architecture 1750-1890. ISBN 978-0-19-284222-0.

- Bourbon, F (1998). Lost Civilizations. New York: Barnes & Noble, Inc.

- Braun, Hugh (1951). An Introduction to English Mediaeval Architecture. London: Faber and Faber.

- Ching, Francis; Jarzombek, Mark; Prakash, Vikram (2006). A Global History of Architecture. Wiley.

- Cole, Emily (2002). Architectural Details. Ivy Press. ISBN 978-1-78240-169-8.

- Copplestone, Trewin, ed. (1963). World architecture – An illustrated history. London: Hamlyn.

- de Martin, Henry (1925). Le Style Louis XV (in French). Flammarion.

- ISBN 978-2738119186.

- Duncan, Alastair (1988). Art déco. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 2-87811-003-X.

- Duncan, Alastair (1994). Art Nouveau. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-20273-9.

- Duncan, Alastair (2009). Art Deco Complete: The Definitive Guide to the Decorative Arts of the 1920s and 1930s. Abrams. ISBN 978-0-8109-8046-4.

- ISBN 978-0-19-882905-8.

- Fortenberry, Diane (2017). The Art Museum (Revised ed.). London: Phaidon Press. ISBN 978-0-7148-7502-6. Archivedfrom the original on 2021-04-23. Retrieved 2021-04-23.

- Hitchcock, Henry-Russell (1958). The Pelican History of Art: Architecture : Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. Penguin Books.

- Hodge, Susie (2019). The Short Story of Architecture. Laurence King Publishing. ISBN 978-1-7862-7370-3.

- Hopkins, Owen (2014). Architectural Styles: A Visual Guide. Laurence King. ISBN 978-178067-163-5.

- Irving, Mark (2019). 1001 Buildings You Must See Before You Die. Cassell Illustrated. ISBN 978-1-78840-176-0.

- Jarzombek, Mark (2013). Architecture of First Societies: a Global History. Wiley Press.

- Jones, Denna, ed. (2014). Architecture The Whole Story. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-29148-1.

- ISBN 978-1-57607-907-2.

- Nuttgens, Patrick (1983). The Story of Architecture. Prentice Hall.

- Renault, Christophe; Lazé, Christophe (2006). les Styles de l'architecture et du mobliier (in French). Editions Jean-Paul Gisserot. ISBN 978-2-87747-465-8.

- Rogers, Richard; Gumuchdjian, Philip; Jones, Denna (2014). Architecture The Whole Story. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-29148-1.

- Shukla, D. N. (1993). Vastu-Sastra: Hindu Science of Architecture. Munshiram Manoharial Publishers. ISBN 978-81-215-0611-3.

- Sinha, Amita (1998). "Design of Settlements in the Vaastu Shastras". Journal of Cultural Geography. 17 (2). Taylor & Francis: 27–41. .

- Sund, July (2019). Exotic: A Fetish for the Foreign. Phaidon. ISBN 978-0-7148-7637-5.

- Texier, Simon (2012). Paris: Panorama de l'architecture (in French). Parigramme. ISBN 978-2-84096-667-8.

- Watkin, David (September 2005). A History of Western Architecture. Hali Publications.

- ISBN 978-0-521-57219-4. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- Modernism

- Banham, Reyner (1 Dec 1980). Theory and Design in the First Machine Age. Architectural Press.

- Curl, James Stevens (2006). A Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture (Paperback) (Second ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 880. ISBN 978-0-19-280630-7. ISBN.

- Curtis, William J. R. (1987). Modern Architecture Since 1900. Phaidon Press.

- Frampton, Kenneth (1992). Modern Architecture, a critical history (Third ed.). Thames & Hudson.

- Jencks, Charles (1993). Modern Movements in Architecture (second ed.). Penguin Books Ltd.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus (28 Mar 1991). Pioneers of Modern Design: From William Morris to Walter Gropius. Penguin Books Ltd.

Further reading

- Sir Banister Fletcher's a History of Architecture ISBN 0-7506-2267-9

External links

- History of architecture at Curlie

- The Society of Architectural Historians web site

- The Society of Architectural Historians of Great Britain web site

- The Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand web site

- European Architectural History Network web site Archived 2018-12-12 at the Wayback Machine

- Western Architecture Timeline

- Extensive collection of source documents in the history, theory and criticism of 20th-century architecture

![Bilzingsleben, possibly built by Homo heidelbergensis, 400–350.000 BCE.[18][19]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/64/Bilzingsleben%2C_Steinrinne%2C_in_der_Ausgrabungshalle-2.jpg/120px-Bilzingsleben%2C_Steinrinne%2C_in_der_Ausgrabungshalle-2.jpg)

![Reconstruction of a Terra Amata dwelling, possibly built by Homo heidelbergensis, 380–230,000 BCE.[20]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e1/Terra-Amata-Hut.gif/120px-Terra-Amata-Hut.gif)

![Reconstructed wooden house (Hemudu, China), 5000-4500 BC[26]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d9/Hemudu_Site_Museum%2C_2017-08-12_13.jpg/120px-Hemudu_Site_Museum%2C_2017-08-12_13.jpg)

![Skara Brae (Scotland), 3200-2200 BC[27]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/2018_07_12_Schottland_%2890%29_Skara_Brae.jpg/120px-2018_07_12_Schottland_%2890%29_Skara_Brae.jpg)

![Columns with clay mosaic cones from the Eanna precinct in Uruk (southern Mesopotamia), Pergamon Museum, Berlin, Germany, unknown architect, 3600-3200 BC[28]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/86/Vorderasiatisches_Museum_Berlin_048.jpg/338px-Vorderasiatisches_Museum_Berlin_048.jpg)

![Ziggurat of Ur, Tell el-Muqayyar, Dhi Qar Province, Iraq, unknown architect, 21st century BC[29]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/93/Ancient_ziggurat_at_Ali_Air_Base_Iraq_2005.jpg/300px-Ancient_ziggurat_at_Ali_Air_Base_Iraq_2005.jpg)

![Tile with a guilloche border from the North-West Palace at Nimrud (now in modern Iraq), British Museum, London, unknown artisan, 883-859 BC[30]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/66/Glazed_Tile.jpg/169px-Glazed_Tile.jpg)

![Reconstruction of the Ishtar Gate, Pergamon Museum, Berlin, Germany, unknown architect, c.605-539 BC[31]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/53/Ishtar_gate_in_Pergamon_museum_in_Berlin..jpg/316px-Ishtar_gate_in_Pergamon_museum_in_Berlin..jpg)

![The Pyramid of Djoser, Saqqara, Egypt, by Imhotep, 2667–2648 BC[34]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/ed/Sakkara_02a.jpg/225px-Sakkara_02a.jpg)

![Great Pyramid of Giza, Giza, Egypt, by Hemiunu, c.2589-2566 BC[35]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e3/Kheops-Pyramid.jpg/367px-Kheops-Pyramid.jpg)

![Interior hall of the rock-cut tomb of Amenemhat, Tomb 2 (BH2), Beni Hasan, Egypt, unknown architect, c.1900 BC[36]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1b/Beni_Hassan_16.jpg/300px-Beni_Hassan_16.jpg)

![Hypostyle Hall of the Karnak Temple Complex, Luxor, Egypt, unknown architect, c.1294–1213 BC[37]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5c/Pillars_of_Great_Hypostyle_Hall_in_Karnak_Luxor_Egypt.JPG/338px-Pillars_of_Great_Hypostyle_Hall_in_Karnak_Luxor_Egypt.JPG)

![Great Temple of Abu Simbel, Egypt, unknown architect, c.1264 BC[38]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9b/Abu_Simbel_Main_Temple_%282346939149%29.jpg/321px-Abu_Simbel_Main_Temple_%282346939149%29.jpg)

![Entrance of the Luxor Temple complex, unknown architect, 1279-1212 BC[39]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/bc/Luxor-Tempel_Pylon_08.jpg/300px-Luxor-Tempel_Pylon_08.jpg)