Anglo-Ethiopian Agreement

The Anglo-Ethiopian Agreement was a joint effort between Ethiopia and the United Kingdom at reestablishing Ethiopian independent statehood following the ousting of Italian troops by combined British and Ethiopian forces in 1941 during the Second World War.

There was a prior Anglo-Ethiopian Agreement signed in 1897. This convention involved Menelik II and it largely dealt with the boundary between Hararghe (Ethiopia) and British Somaliland.

Under the agreement

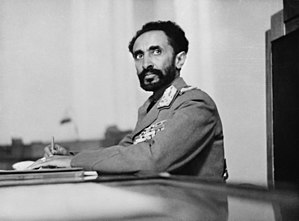

After the return of Ethiopian emperor

The Ethiopians soon found the implementation of this agreement intolerable, although they found it a slight improvement over the prior relationship, in which Ethiopia was treated as an occupied enemy nation. Haile Selassie described one aspect of the prior relationship, "they took all the military equipment captured in Our country... openly and boldly saying that it should not be left for the service of blacks."

A British-trained police force eventually replaced the former police who were in the service of local

British Ogaden

British Military Administration in Ogaden and Haud | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1941–1955 | |||||||||

|

Flag | |||||||||

| Status |

| ||||||||

| Capital | Kebri Dahar | ||||||||

| Common languages | Somali | ||||||||

| Historical era | World War II • Cold War | ||||||||

| March 1941 | |||||||||

• Ogaden relinquished | 23 September 1948 | ||||||||

• Haud relinquished | 28 February 1955 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Ethiopia | ||||||||

The British Military Administration in Ogaden, or simply British Ogaden, was the period of British Military Administration from 1941 until 1955. The British came to control

The process of reversing the effects of World War II on Ethiopia did not completely end until 1955, when Ethiopia was restored to its internationally recognised borders of 1935, from before the Italian invasion. The British ceded Ogaden to Ethiopia in 1948, with the remaining British control over Haud being relinquished in 1955.[11] After the decision to cede Ogaden to Ethiopia became public there were numerous calls, as well as violent insurgencies, intended to reverse this decision. The movement to gain self-determination from Addis Ababa has continued into the 21st century.[12]

Negotiating a new agreement

Despite Ethiopian distaste for the agreement, both the Emperor and his innermost group of ministers were reluctant to actually submit the notice required to end the agreement. A set of proposals for a new agreement submitted to the British at the beginning of 1944 was summarily rejected. As John Spencer, an American advisor to Ethiopia in international law during this period, explains, "They feared retaliation in the form of a re-occupation of the province of

The initial British response was silence. Only after the Ethiopian government reminded them of the expiry of the agreement 16 August and that they were looking forward receiving possession of the railway and administration of the

See also

References

- ^ Haile Selassie, My Life and Ethiopia's Progress Volume Two: Addis Abebe 1966 E.C. (Chicago: Frontline Distribution, 1999), p. 176

- ^ a b "Ethiopia: Ethiopia in World War II", Library of Congress website (accessed 30 January 2011)

- ISSN 0740-9133.

- ^ Haile Selassie, My Life and Ethiopia's Progress, p. 173

- ^ John Spencer, Ethiopia at Bay: A personal account of the Haile Selassie years (Algonac: Reference Publications, 1984), p. 106

- ^ Spencer, Ethiopia at Bay, p. 102; Mauri A., "The re-establishment of the national monetary and banking system in Ethiopia", The South African Journal of Economic History, Vol. 24, n. 2, p. 91

- ^ Super powers in the Horn of Africa - Page 48, 1987, Madan Sauldie

- ^ Cahiers d'études africaines - Volume 2 - Page 65

- ^ Spencer, Ethiopia at Bay, p. 142

- ^ Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: O-X - Page 1026, Siegbert Uhlig - 2010

- ^ a b Spencer, Ethiopia at Bay, p. 152

- ^ Vaughan, Sarah. "Ethiopia, Somalia, and the Ogaden: Still a Running Sore at the Heart of the Horn of Africa." Secessionism in African Politics. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, 2019. 91-123.

- ^ Spencer, Ethiopia at Bay, p. 143

- ^ Spencer, Ethiopia at Bay, p. 144

- ^ Spencer, Ethiopia at Bay, pp. 145-153

- ^ "The Negus Negotiates", Time 1 January 1945 (accessed 14 May 2009)

- ^ Bahru Zewde, A History of Modern Ethiopia, second edition (Oxford: James Currey, 2001), p. 180

Further reading

- "Consequences of the British Occupation of Ethiopia During World II" by Theodore M. Vestal

- Harold Courlander, "The Emperor Wore Clothes: Visiting Haile Sellassie in 1943", American Scholar, 58 (1959), pp. 277ff.

- Arnaldo Mauri, "The re-establishment of the national monetary and banking system in Ethiopia, 1941-1963", The South African Journal of Economic History, Vol. 24, n. 2, 2009, pp. 82–130.