Animal testing

Wistar laboratory rat | |

| Description | Around 50–100 million vertebrate animals are used in experiments annually. |

|---|---|

| Subjects | Animal testing, science, medicine, animal welfare, animal rights, ethics |

Animal testing, also known as animal experimentation, animal research, and in vivo testing, is the use of

It was estimated in 2010 that the annual use of

Animal testing is regulated differently in different countries: in some cases it is strictly controlled while others have more relaxed regulations. There are ongoing debates about the ethics and necessity of animal testing. Proponents argue that it has led to significant advancements in medicine and other fields while opponents raise concerns about cruelty towards animals and question its effectiveness.[11][12]

There are efforts underway to find alternatives to animal testing such as computer simulation models, organs-on-chips technology[13] that mimics human organs for lab tests, microdosing techniques which involve administering small doses of test compounds to volunteers instead of animals for safety tests or drug screenings; positron emission tomography (PET) scans which allow scanning of the human brain without harming humans; comparative epidemiological studies among human populations; simulators and computer programs for teaching purposes; among others.[14][15][16]

Animal testing can be inaccurate because experiments on animals do not always correctly mimic human body responses.[17]

Definitions

The terms animal testing, animal experimentation, animal research, in vivo testing, and vivisection have similar denotations but different connotations. Literally, "vivisection" means "live sectioning" of an animal, and historically referred only to experiments that involved the dissection of live animals. The term is occasionally used to refer pejoratively to any experiment using living animals; for example, the Encyclopædia Britannica defines "vivisection" as: "Operation on a living animal for experimental rather than healing purposes; more broadly, all experimentation on live animals",[18][19][20] although dictionaries point out that the broader definition is "used only by people who are opposed to such work".[21][22] The word has a negative connotation, implying torture, suffering, and death.[23] The word "vivisection" is preferred by those opposed to this research, whereas scientists typically use the term "animal experimentation".[24][25]

The following text excludes as much as possible practices related to in vivo veterinary surgery, which is left to the discussion of vivisection.

History

The earliest references to animal testing are found in the writings of the

Animals have repeatedly been used throughout the history of biomedical research. In 1831, the founders of the

Historical debate

As the experimentation on animals increased, especially the practice of vivisection, so did criticism and controversy. In 1655, the advocate of Galenic physiology Edmund O'Meara said that "the miserable torture of vivisection places the body in an unnatural state".[44][45] O'Meara and others argued pain could affect animal physiology during vivisection, rendering results unreliable. There were also objections ethically, contending that the benefit to humans did not justify the harm to animals.[45] Early objections to animal testing also came from another angle—many people believed animals were inferior to humans and so different that results from animals could not be applied to humans.[2][45]

On the other side of the debate, those in favor of animal testing held that experiments on animals were necessary to advance medical and biological knowledge. Claude Bernard—who is sometimes known as the "prince of vivisectors"[42] and the father of physiology, and whose wife, Marie Françoise Martin, founded the first anti-vivisection society in France in 1883[46]—famously wrote in 1865 that "the science of life is a superb and dazzlingly lighted hall which may be reached only by passing through a long and ghastly kitchen".[47] Arguing that "experiments on animals [. . .] are entirely conclusive for the toxicology and hygiene of man [. . . T]he effects of these substances are the same on man as on animals, save for differences in degree",[43] Bernard established animal experimentation as part of the standard scientific method.[48]

In 1896, the physiologist and physician

In 1822, the first animal protection law was enacted in the British parliament, followed by the Cruelty to Animals Act (1876), the first law specifically aimed at regulating animal testing. The legislation was promoted by Charles Darwin, who wrote to Ray Lankester in March 1871: "You ask about my opinion on vivisection. I quite agree that it is justifiable for proper investigations on physiology; but not for mere damnable and detestable curiosity. It is a subject which makes me sick with horror, so I will not say another word about it, else I shall not sleep to-night."[51][52] In response to the lobbying by anti-vivisectionists, several organizations were set up in Britain to defend animal research: The Physiological Society was formed in 1876 to give physiologists "mutual benefit and protection",[53] the Association for the Advancement of Medicine by Research was formed in 1882 and focused on policy-making, and the Research Defence Society (now Understanding Animal Research) was formed in 1908 "to make known the facts as to experiments on animals in this country; the immense importance to the welfare of mankind of such experiments and the great saving of human life and health directly attributable to them".[54]

Opposition to the use of animals in medical research first arose in the United States during the 1860s, when

Real progress in thinking about animal rights build on the "theory of justice" (1971) by the philosopher John Rawls and work on ethics by philosopher Peter Singer.[2]

Care and use of animals

Regulations and laws

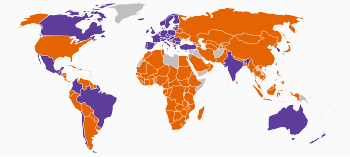

| | Nationwide ban on all cosmetic testing on animals | | Partial ban on cosmetic testing on animals1 |

| | Ban on the sale of cosmetics tested on animals | | No ban on any cosmetic testing on animals |

| | Unknown |

The regulations that apply to animals in laboratories vary across species. In the U.S., under the Animal Welfare Act and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (the Guide), published by the National Academy of Sciences, any procedure can be performed on an animal if it can be successfully argued that it is scientifically justified. Researchers are required to consult with the institution's veterinarian and its Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), which every research facility is obliged to maintain.[56] The IACUC must ensure that alternatives, including non-animal alternatives, have been considered, that the experiments are not unnecessarily duplicative, and that pain relief is given unless it would interfere with the study. The IACUCs regulate all vertebrates in testing at institutions receiving federal funds in the USA. Although the Animal Welfare Act does not include purpose-bred rodents and birds, these species are equally regulated under Public Health Service policies that govern the IACUCs.[57][58] The Public Health Service policy oversees the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The CDC conducts infectious disease research on nonhuman primates, rabbits, mice, and other animals, while FDA requirements cover use of animals in pharmaceutical research.[59] Animal Welfare Act (AWA) regulations are enforced by the USDA, whereas Public Health Service regulations are enforced by OLAW and in many cases by AAALAC.

According to the 2014 U.S. Department of Agriculture Office of the Inspector General (OIG) report—which looked at the oversight of animal use during a three-year period—"some Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees ...did not adequately approve, monitor, or report on experimental procedures on animals". The OIG found that "as a result, animals are not always receiving basic humane care and treatment and, in some cases, pain and distress are not minimized during and after experimental procedures". According to the report, within a three-year period, nearly half of all American laboratories with regulated species were cited for AWA violations relating to improper IACUC oversight.[60] The USDA OIG made similar findings in a 2005 report.[61] With only a broad number of 120 inspectors, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) oversees more than 12,000 facilities involved in research, exhibition, breeding, or dealing of animals.[59] Others have criticized the composition of IACUCs, asserting that the committees are predominantly made up of animal researchers and university representatives who may be biased against animal welfare concerns.[62]

Larry Carbone, a laboratory animal veterinarian, writes that, in his experience, IACUCs take their work very seriously regardless of the species involved, though the use of

Scientists in India are protesting a recent guideline issued by the University Grants Commission to ban the use of live animals in universities and laboratories.[65]

Numbers

Accurate global figures for animal testing are difficult to obtain; it has been estimated that 100 million vertebrates are experimented on around the world every year,[66] 10–11 million of them in the EU.[67] The Nuffield Council on Bioethics reports that global annual estimates range from 50 to 100 million animals. None of the figures include invertebrates such as shrimp and fruit flies.[68]

The USDA/APHIS has published the 2016 animal research statistics. Overall, the number of animals (covered by the Animal Welfare Act) used in research in the US rose 6.9% from 767,622 (2015) to 820,812 (2016).[69] This includes both public and private institutions. By comparing with EU data, where all vertebrate species are counted, Speaking of Research estimated that around 12 million vertebrates were used in research in the US in 2016.[70] A 2015 article published in the Journal of Medical Ethics, argued that the use of animals in the US has dramatically increased in recent years. Researchers found this increase is largely the result of an increased reliance on genetically modified mice in animal studies.[71]

In 1995, researchers at Tufts University Center for Animals and Public Policy estimated that 14–21 million animals were used in American laboratories in 1992, a reduction from a high of 50 million used in 1970.[72] In 1986, the U.S. Congress Office of Technology Assessment reported that estimates of the animals used in the U.S. range from 10 million to upwards of 100 million each year, and that their own best estimate was at least 17 million to 22 million.[73] In 2016, the Department of Agriculture listed 60,979 dogs, 18,898 cats, 71,188 non-human primates, 183,237 guinea pigs, 102,633 hamsters, 139,391 rabbits, 83,059 farm animals, and 161,467 other mammals, a total of 820,812, a figure that includes all mammals except purpose-bred mice and rats. The use of dogs and cats in research in the U.S. decreased from 1973 to 2016 from 195,157 to 60,979, and from 66,165 to 18,898, respectively.[70]

In the UK, Home Office figures show that 3.79 million procedures were carried out in 2017.[74] 2,960 procedures used non-human primates, down over 50% since 1988. A "procedure" refers here to an experiment that might last minutes, several months, or years. Most animals are used in only one procedure: animals are frequently euthanized after the experiment; however death is the endpoint of some procedures.[68] The procedures conducted on animals in the UK in 2017 were categorised as –

- 43% (1.61 million) were assessed as sub-threshold

- 4% (0.14 million) were assessed as non-recovery

- 36% (1.35 million) were assessed as mild

- 15% (0.55 million) were assessed as moderate

- 4% (0.14 million) were assessed as severe[75]

A 'severe' procedure would be, for instance, any test where death is the end-point or fatalities are expected, whereas a 'mild' procedure would be something like a blood test or an MRI scan.[74]

The Three Rs

The Three Rs (3Rs) are guiding principles for more ethical use of animals in testing. These were first described by W.M.S. Russell and R.L. Burch in 1959.[76] The 3Rs state:

- Replacement which refers to the preferred use of non-animal methods over animal methods whenever it is possible to achieve the same scientific aims. These methods include computer modeling.

- Reduction which refers to methods that enable researchers to obtain comparable levels of information from fewer animals, or to obtain more information from the same number of animals.

- Refinement which refers to methods that alleviate or minimize potential pain, suffering or distress, and enhance animal welfare for the animals used. These methods include non-invasive techniques.[77]

The 3Rs have a broader scope than simply encouraging alternatives to animal testing, but aim to improve animal welfare and scientific quality where the use of animals can not be avoided. These 3Rs are now implemented in many testing establishments worldwide and have been adopted by various pieces of legislation and regulations.[2]

Despite the widespread acceptance of the 3Rs, many countries—including Canada, Australia, Israel, South Korea, and Germany—have reported rising experimental use of animals in recent years with increased use of mice and, in some cases, fish while reporting declines in the use of cats, dogs, primates, rabbits, guinea pigs, and hamsters. Along with other countries, China has also escalated its use of GM animals, resulting in an increase in overall animal use.[78][79][80][81][82][83][excessive citations]

Invertebrates

Although many more invertebrates than vertebrates are used in animal testing, these studies are largely unregulated by law. The most frequently used invertebrate species are

Several invertebrate systems are considered acceptable alternatives to vertebrates in early-stage discovery screens.[92] Because of similarities between the innate immune system of insects and mammals, insects can replace mammals in some types of studies. Drosophila melanogaster and the Galleria mellonella waxworm have been particularly important for analysis of virulence traits of mammalian pathogens.[89][90] Waxworms and other insects have also proven valuable for the identification of pharmaceutical compounds with favorable bioavailability.[91] The decision to adopt such models generally involves accepting a lower degree of biological similarity with mammals for significant gains in experimental throughput.

Vertebrates

In the U.S., the numbers of rats and mice used is estimated to be from 11 million[70] to between 20 and 100 million a year.[93] Other rodents commonly used are guinea pigs, hamsters, and gerbils. Mice are the most commonly used vertebrate species because of their size, low cost, ease of handling, and fast reproduction rate.[94][95] Mice are widely considered to be the best model of inherited human disease and share 95% of their genes with humans.[94] With the advent of genetic engineering technology, genetically modified mice can be generated to order and can provide models for a range of human diseases.[94] Rats are also widely used for physiology, toxicology and cancer research, but genetic manipulation is much harder in rats than in mice, which limits the use of these rodents in basic science.[96]

Over 500,000 fish and 9,000 amphibians were used in the UK in 2016.

Cats

Cats are most commonly used in neurological research. In 2016, 18,898 cats were used in the United States alone,[70] around a third of which were used in experiments which have the potential to cause "pain and/or distress"[100] though only 0.1% of cat experiments involved potential pain which was not relieved by anesthetics/analgesics. In the UK, just 198 procedures were carried out on cats in 2017. The number has been around 200 for most of the last decade.[97]

Dogs

Dogs are widely used in biomedical research, testing, and education—particularly

The U.S. Department of Agriculture's Animal Welfare Report shows that 60,979 dogs were used in USDA-registered facilities in 2016.[70] In the UK, according to the UK Home Office, there were 3,847 procedures on dogs in 2017.[97] Of the other large EU users of dogs, Germany conducted 3,976 procedures on dogs in 2016[105] and France conducted 4,204 procedures in 2016.[106] In both cases this represents under 0.2% of the total number of procedures conducted on animals in the respective countries.

Zebrafish

Zebrafish are commonly used for the basic study and development of various cancers. Used to explore the immune system and genetic strains. They are low in cost, small size, fast reproduction rate, and able to observe cancer cells in real time. Humans and zebrafish share neoplasm similarities which is why they are used for research. The National Library of Medicine shows many examples of the types of cancer zebrafish are used in. The use of zebrafish have allowed them to find differences between MYC-driven pre-B vs T-ALL and be exploited to discover novel pre-B ALL therapies on acute lymphocytic leukemia.[107][108]

The National Library of Medicine also explains how a neoplasm is difficult to diagnose at an early stage. Understanding the molecular mechanism of digestive tract tumorigenesis and searching for new treatments is the current research. Zebrafish and humans share similar gastric cancer cells in the gastric cancer xenotransplantation model. This allowed researchers to find that Triphala could inhibit the growth and metastasis of gastric cancer cells. Since zebrafish liver cancer genes are related with humans they have become widely used in liver cancer search, as will as many other cancers.[109]

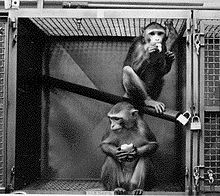

Non-human primates

Non-human primates (NHPs) are used in toxicology tests, studies of AIDS and hepatitis, studies of

In a survey in 2003, it was found that 89% of singly-housed primates exhibited self-injurious or abnormal stereotypyical behaviors including pacing, rocking, hair pulling, and biting among others.[115]

The first transgenic primate was produced in 2001, with the development of a method that could introduce new genes into a

Sources

Animals used by laboratories are largely supplied by specialist dealers. Sources differ for vertebrate and invertebrate animals. Most laboratories breed and raise flies and worms themselves, using strains and mutants supplied from a few main stock centers.

In the U.S., Class A breeders are licensed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) to sell animals for research purposes, while Class B dealers are licensed to buy animals from "random sources" such as auctions, pound seizure, and newspaper ads. Some Class B dealers have been accused of kidnapping pets and illegally trapping strays, a practice known as bunching.[124][125][126][127][128][129] It was in part out of public concern over the sale of pets to research facilities that the 1966 Laboratory Animal Welfare Act was ushered in—the Senate Committee on Commerce reported in 1966 that stolen pets had been retrieved from Veterans Administration facilities, the Mayo Institute, the University of Pennsylvania, Stanford University, and Harvard and Yale Medical Schools.[130] The USDA recovered at least a dozen stolen pets during a raid on a Class B dealer in Arkansas in 2003.[131]

Four states in the U.S.—Minnesota, Utah, Oklahoma, and Iowa—require their shelters to provide animals to research facilities. Fourteen states explicitly prohibit the practice, while the remainder either allow it or have no relevant legislation.[132]

In the European Union, animal sources are governed by Council Directive 86/609/EEC, which requires lab animals to be specially bred, unless the animal has been lawfully imported and is not a wild animal or a stray. The latter requirement may also be exempted by special arrangement.

Pain and suffering

The extent to which animal testing causes pain and suffering, and the capacity of animals to experience and comprehend them, is the subject of much debate.[138][139]

According to the USDA, in 2016 501,560 animals (61%) (not including rats, mice, birds, or invertebrates) were used in procedures that did not include more than momentary pain or distress. 247,882 (31%) animals were used in procedures in which pain or distress was relieved by anesthesia, while 71,370 (9%) were used in studies that would cause pain or distress that would not be relieved.[70]

Since 2014, in the UK, every research procedure was retrospectively assessed for severity. The five categories are "sub-threshold", "mild", "moderate", "severe" and "non-recovery", the latter being procedures in which an animal is anesthetized and subsequently killed without recovering consciousness. In 2017, 43% (1.61 million) were assessed as sub-threshold, 4% (0.14 million) were assessed as non-recovery, 36% (1.35 million) were assessed as mild, 15% (0.55 million) were assessed as moderate and 4% (0.14 million) were assessed as severe.[75]

The idea that animals might not feel pain as human beings feel it traces back to the 17th-century French philosopher,

) protects some invertebrate species if they are being used in animal testing.In the U.S., the defining text on animal welfare regulation in animal testing is the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.[148] This defines the parameters that govern animal testing in the U.S. It states "The ability to experience and respond to pain is widespread in the animal kingdom...Pain is a stressor and, if not relieved, can lead to unacceptable levels of stress and distress in animals." The Guide states that the ability to recognize the symptoms of pain in different species is vital in efficiently applying pain relief and that it is essential for the people caring for and using animals to be entirely familiar with these symptoms. On the subject of analgesics used to relieve pain, the Guide states "The selection of the most appropriate analgesic or anesthetic should reflect professional judgment as to which best meets clinical and humane requirements without compromising the scientific aspects of the research protocol". Accordingly, all issues of animal pain and distress, and their potential treatment with analgesia and anesthesia, are required regulatory issues in receiving animal protocol approval.[149] Currently, traumatic methods of marking laboratory animals are being replaced with non-invasive alternatives.[150][151]

In 2019, Katrien Devolder and Matthias Eggel proposed gene editing research animals to remove the ability to feel pain. This would be an intermediate step towards eventually stopping all experimentation on animals and adopting alternatives.[152] Additionally, this would not stop research animals from experiencing psychological harm.

Euthanasia

Regulations require that scientists use as few animals as possible, especially for terminal experiments.[153] However, while policy makers consider suffering to be the central issue and see animal euthanasia as a way to reduce suffering, others, such as the RSPCA, argue that the lives of laboratory animals have intrinsic value.[154] Regulations focus on whether particular methods cause pain and suffering, not whether their death is undesirable in itself.[155] The animals are euthanized at the end of studies for sample collection or post-mortem examination; during studies if their pain or suffering falls into certain categories regarded as unacceptable, such as depression, infection that is unresponsive to treatment, or the failure of large animals to eat for five days;[156] or when they are unsuitable for breeding or unwanted for some other reason.[157]

Methods of euthanizing laboratory animals are chosen to induce rapid unconsciousness and death without pain or distress.

Research classification

Pure research

Basic or pure research investigates how organisms behave, develop, and function. Those opposed to animal testing object that pure research may have little or no practical purpose, but researchers argue that it forms the necessary basis for the development of applied research, rendering the distinction between pure and applied research—research that has a specific practical aim—unclear.

- Studies on transposons into their genomes, or specific genes are deleted by gene targeting.[163][164] By studying the changes in development these changes produce, scientists aim to understand both how organisms normally develop, and what can go wrong in this process. These studies are particularly powerful since the basic controls of development, such as the homeobox genes, have similar functions in organisms as diverse as fruit flies and man.[165][166]

- Experiments into behavior, to understand how organisms detect and interact with each other and their environment, in which fruit flies, worms, mice, and rats are all widely used.[167][168] Studies of brain function, such as memory and social behavior, often use rats and birds.[169][170] For some species, behavioral research is combined with enrichment strategies for animals in captivity because it allows them to engage in a wider range of activities.[171]

- Breeding experiments to study evolution and genetics. Laboratory mice, flies, fish, and worms are inbred through many generations to create strains with defined characteristics.[172] These provide animals of a known genetic background, an important tool for genetic analyses. Larger mammals are rarely bred specifically for such studies due to their slow rate of reproduction, though some scientists take advantage of inbred domesticated animals, such as dog or cattle breeds, for comparative purposes. Scientists studying how animals evolve use many animal species to see how variations in where and how an organism lives (their niche) produce adaptations in their physiology and morphology. As an example, sticklebacks are now being used to study how many and which types of mutations are selected to produce adaptations in animals' morphology during the evolution of new species.[173][174]

Applied research

Applied research aims to solve specific and practical problems. These may involve the use of

- diabetes,[176] or even transgenic mice that carry the same mutations that occur during the development of cancer.[177] These models allow investigations on how and why the disease develops, as well as providing ways to develop and test new treatments.[178] The vast majority of these transgenic models of human disease are lines of mice, the mammalian species in which genetic modification is most efficient.[94] Smaller numbers of other animals are also used, including rats, pigs, sheep, fish, birds, and amphibians.[136]

- Studies on models of naturally occurring disease and condition. Certain domestic and wild animals have a natural propensity or predisposition for certain conditions that are also found in humans. Cats are used as a model to develop immunodeficiency virus vaccines and to study FIV and Feline leukemia virus.[179][180] Certain breeds of dog experience narcolepsy making them the major model used to study the human condition. Armadillos and humans are among only a few animal species that naturally have leprosy; as the bacteria responsible for this disease cannot yet be grown in culture, armadillos are the primary source of bacilli used in leprosy vaccines.[162]

- Studies on induced animal models of human diseases. Here, an animal is treated so that it develops

- Animal testing has also included the use of placebo testing. In these cases animals are treated with a substance that produces no pharmacological effect, but is administered in order to determine any biological alterations due to the experience of a substance being administered, and the results are compared with those obtained with an active compound.

Xenotransplantation

Documents released to the news media by the animal rights organization Uncaged Campaigns showed that, between 1994 and 2000, wild baboons imported to the UK from Africa by Imutran Ltd, a subsidiary of Novartis Pharma AG, in conjunction with Cambridge University and Huntingdon Life Sciences, to be used in experiments that involved grafting pig tissues, had serious and sometimes fatal injuries. A scandal occurred when it was revealed that the company had communicated with the British government in an attempt to avoid regulation.[189][190]

Toxicology testing

Toxicology testing, also known as safety testing, is conducted by pharmaceutical companies testing drugs, or by contract animal testing facilities, such as

Toxicology tests are used to examine finished products such as

The substances are applied to the skin or dripped into the eyes; injected

There are several different types of

Irritancy can be measured using the Draize test, where a test substance is applied to an animal's eyes or skin, usually an albino rabbit. For Draize eye testing, the test involves observing the effects of the substance at intervals and grading any damage or irritation, but the test should be halted and the animal killed if it shows "continuing signs of severe pain or distress".[199] The Humane Society of the United States writes that the procedure can cause redness, ulceration, hemorrhaging, cloudiness, or even blindness.[200] This test has also been criticized by scientists for being cruel and inaccurate, subjective, over-sensitive, and failing to reflect human exposures in the real world.[201] Although no accepted in vitro alternatives exist, a modified form of the Draize test called the low volume eye test may reduce suffering and provide more realistic results and this was adopted as the new standard in September 2009.[202][203] However, the Draize test will still be used for substances that are not severe irritants.[203]

The most stringent tests are reserved for drugs and foodstuffs. For these, a number of tests are performed, lasting less than a month (acute), one to three months (subchronic), and more than three months (chronic) to test general toxicity (damage to organs), eye and skin irritancy,

These toxicity tests provide, in the words of a 2006

Scientists face growing pressure to move away from using traditional animal toxicity tests to determine whether manufactured chemicals are safe.[209] Among variety of approaches to toxicity evaluation the ones which have attracted increasing interests are in vitro cell-based sensing methods applying fluorescence.[210]

Cosmetics testing

Cosmetics testing on animals is particularly controversial. Such tests, which are still conducted in the U.S., involve general toxicity, eye and skin irritancy,

Cosmetics testing on animals is banned in India, the United Kingdom, the European Union,

Drug testing

Before the early 20th century, laws regulating drugs were lax. Currently, all new pharmaceuticals undergo rigorous animal testing before being licensed for human use. Tests on pharmaceutical products involve:

- metabolic tests, investigating intramuscularly, or transdermally.

- toxicology tests, which gauge acute, sub-acute, and chronic toxicity. Acute toxicity is studied by using a rising dose until signs of toxicity become apparent. Current European legislation demands that "acute toxicity tests must be carried out in two or more mammalian species" covering "at least two different routes of administration".[218] Sub-acute toxicity is where the drug is given to the animals for four to six weeks in doses below the level at which it causes rapid poisoning, in order to discover if any toxic drug metabolites build up over time. Testing for chronic toxicity can last up to two years and, in the European Union, is required to involve two species of mammals, one of which must be non-rodent.[219]

- efficacy studies, which test whether experimental drugs work by inducing the appropriate illness in animals. The drug is then administered in a dose-responsecurve.

- Specific tests on reproductive function, embryonic toxicity, or carcinogenic potential can all be required by law, depending on the result of other studies and the type of drug being tested.

Education

It is estimated that 20 million animals are used annually for educational purposes in the United States including, classroom observational exercises, dissections and live-animal surgeries.

The Sonoran Arthropod Institute hosts an annual Invertebrates in Education and Conservation Conference to discuss the use of invertebrates in education.[226] There also are efforts in many countries to find alternatives to using animals in education.[227] The NORINA database, maintained by Norecopa, lists products that may be used as alternatives or supplements to animal use in education, and in the training of personnel who work with animals.[228] These include alternatives to dissection in schools. InterNICHE has a similar database and a loans system.[229]

In November 2013, the U.S.-based company Backyard Brains released for sale to the public what they call the "Roboroach", an "electronic backpack" that can be attached to cockroaches. The operator is required to amputate a cockroach's antennae, use sandpaper to wear down the shell, insert a wire into the thorax, and then glue the electrodes and circuit board onto the insect's back. A mobile phone app can then be used to control it via Bluetooth.[230] It has been suggested that the use of such a device may be a teaching aid that can promote interest in science. The makers of the "Roboroach" have been funded by the National Institute of Mental Health and state that the device is intended to encourage children to become interested in neuroscience.[230][231]

Defense

Animals are used by the military to develop weapons, vaccines, battlefield surgical techniques, and defensive clothing.[161] For example, in 2008 the United States Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency used live pigs to study the effects of improvised explosive device explosions on internal organs, especially the brain.[232]

In the US military,

Besides the United States, six out of 28 NATO countries, including Poland and Denmark, use live animals for combat medic training.[233]

Ethics

Most animals are

Viewpoints

| Part of a series on |

| Animal rights |

|---|

The moral and ethical questions raised by performing experiments on animals are subject to debate, and viewpoints have shifted significantly over the 20th century.[246] There remain disagreements about which procedures are useful for which purposes, as well as disagreements over which ethical principles apply to which species.

A 2015 Gallup poll found that 67% of Americans were "very concerned" or "somewhat concerned" about animals used in research.[247] A Pew poll taken the same year found 50% of American adults opposed the use of animals in research.[248]

Still, a wide range of viewpoints exist. The view that animals have moral rights (

Governments such as the Netherlands and New Zealand have responded to the public's concerns by outlawing invasive experiments on certain classes of non-human primates, particularly the

The British government has required that the cost to animals in an experiment be weighed against the gain in knowledge.[262] Some medical schools and agencies in China, Japan, and South Korea have built cenotaphs for killed animals.[263] In Japan there are also annual memorial services (Ireisai 慰霊祭) for animals sacrificed at medical school.

Various specific cases of animal testing have drawn attention, including both instances of beneficial scientific research, and instances of alleged ethical violations by those performing the tests. The fundamental properties of

Concerns have been raised over the mistreatment of primates undergoing testing. In 1985 the case of

Threats to researchers

Threats of violence to animal researchers are not uncommon.[vague][275]

In 2006, a primate researcher at the

In 1997, PETA filmed staff from Huntingdon Life Sciences, showing dogs being mistreated.[280][281] The employees responsible were dismissed,[282] with two given community service orders and ordered to pay £250 costs, the first lab technicians to have been prosecuted for animal cruelty in the UK.[283] The Stop Huntingdon Animal Cruelty campaign used tactics ranging from non-violent protest to the alleged firebombing of houses owned by executives associated with HLS's clients and investors. The Southern Poverty Law Center, which monitors US domestic extremism, has described SHAC's modus operandi as "frankly terroristic tactics similar to those of anti-abortion extremists", and in 2005 an official with the FBI's counter-terrorism division referred to SHAC's activities in the United States as domestic terrorist threats.[284][285] 13 members of SHAC were jailed for between 15 months and eleven years on charges of conspiracy to blackmail or harm HLS and its suppliers.[286][287]

These attacks—as well as similar incidents that caused the Southern Poverty Law Center to declare in 2002 that the animal rights movement had "clearly taken a turn toward the more extreme"—prompted the US government to pass the Animal Enterprise Terrorism Act and the UK government to add the offense of "Intimidation of persons connected with animal research organisation" to the Serious Organised Crime and Police Act 2005. Such legislation and the arrest and imprisonment of activists may have decreased the incidence of attacks.[288]

Scientific criticism

Systematic reviews have pointed out that animal testing often fails to accurately mirror outcomes in humans.[289][290] For instance, a 2013 review noted that some 100 vaccines have been shown to prevent HIV in animals, yet none of them have worked on humans.[290] Effects seen in animals may not be replicated in humans, and vice versa. Many corticosteroids cause birth defects in animals, but not in humans. Conversely, thalidomide causes serious birth defects in humans, but not in some animals such as mice (however, it does cause birth defects in rabbits).[291] A 2004 paper concluded that much animal research is wasted because systemic reviews are not used, and due to poor methodology.[292] A 2006 review found multiple studies where there were promising results for new drugs in animals, but human clinical studies did not show the same results. The researchers suggested that this might be due to researcher bias, or simply because animal models do not accurately reflect human biology.[293] Lack of meta-reviews may be partially to blame.[291] Poor methodology is an issue in many studies. A 2009 review noted that many animal experiments did not use blinded experiments, a key element of many scientific studies in which researchers are not told about the part of the study they are working on to reduce bias.[291][294] A 2021 paper found, in a sample of Open Access Alzheimer Disease studies, that if the authors omit from the title that the experiment was performed in mice, the News Headline follow suit, and that also the Twitter repercussion is higher.[295]

Activism

There are various examples of activists utilizing Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests to obtain information about taxpayer funding of animal testing. For example, the White Coat Waste Project, a group of activists that hold that taxpayers should not have

to pay $20 billion every year for experiments on animals,

Alternatives

Most scientists and governments state that animal testing should cause as little suffering to animals as possible, and that animal tests should only be performed where necessary.

The scientists and engineers at Harvard's Wyss Institute have created "organs-on-a-chip", including the "lung-on-a-chip" and "gut-on-a-chip". Researchers at cellasys in Germany developed a "skin-on-a-chip".[305] These tiny devices contain human cells in a 3-dimensional system that mimics human organs. The chips can be used instead of animals in in vitro disease research, drug testing, and toxicity testing.[306] Researchers have also begun using 3-D bioprinters to create human tissues for in vitro testing.[307]

Another non-animal research method is in silico or computer simulation and mathematical modeling which seeks to investigate and ultimately predict toxicity and drug effects on humans without using animals. This is done by investigating test compounds on a molecular level using recent advances in technological capabilities with the ultimate goal of creating treatments unique to each patient.[308][309]

Microdosing is another alternative to the use of animals in experimentation. Microdosing is a process whereby volunteers are administered a small dose of a test compound allowing researchers to investigate its pharmacological affects without harming the volunteers. Microdosing can replace the use of animals in pre-clinical drug screening and can reduce the number of animals used in safety and toxicity testing.[310]

Additional alternative methods include positron emission tomography (PET), which allows scanning of the human brain in vivo,[311] and comparative epidemiological studies of disease risk factors among human populations.[312]

Simulators and computer programs have also replaced the use of animals in dissection, teaching and training exercises.[313][314]

Official bodies such as the European Centre for the Validation of Alternative Test Methods of the European Commission, the Interagency Coordinating Committee for the Validation of Alternative Methods in the US,[315] ZEBET in Germany,[316] and the Japanese Center for the Validation of Alternative Methods[317] (among others) also promote and disseminate the 3Rs. These bodies are mainly driven by responding to regulatory requirements, such as supporting the cosmetics testing ban in the EU by validating alternative methods.

The European Partnership for Alternative Approaches to Animal Testing serves as a liaison between the European Commission and industries.[318] The European Consensus Platform for Alternatives coordinates efforts amongst EU member states.[319]

Academic centers also investigate alternatives, including the Center for Alternatives to Animal Testing at the Johns Hopkins University[320] and the NC3Rs in the UK.[321]

See also

References

Citations

- ^ ""Introduction", Select Committee on Animals in Scientific Procedures Report". UK Parliament. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- ^ S2CID 206268293.

- PMID 21731811.

- PMID 17545991.

- ^ Meredith Cohn (26 August 2010). "Alternatives to Animal Testing Gaining Ground," The Baltimore Sun.

- S2CID 211261775.

- ^ "REPORT FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE COUNCIL AND THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT Seventh Report on the Statistics on the Number of Animals used for Experimental and other Scientific Purposes in the Member States of the European Union". No. Document 52013DC0859. EUR-Lex. 12 May 2013.

- ^ Carbone, Larry. (2004). What Animals Want: Expertise and Advocacy in Laboratory Animal Welfare Policy.

- ^ "EU statistics show decline in animal research numbers". Speaking of Research. 2013. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- ^ "U.S. Will No Longer Require Animal Testing for New Drugs". 13 January 2022.

- S2CID 260938742.

- PMID 33331099.

- S2CID 221621465.

- S2CID 3378256.

- S2CID 226204296.

- S2CID 259915886.

- ^ "Using animals in experiments | The Humane Society of the United States". www.humanesociety.org. Retrieved 20 February 2024.

- ^ ISBN 1-85649-732-1.

- ^ "Vivisection". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Archived from the original on 1 January 2008.

- ^ "Vivisection FAQ" (PDF). British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 May 2015.

- ^ "Vivisection". Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- ^ "Vivisection". Definition of VIVISECTION. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- ^ a b Carbone, p. 22.

- PMID 10089552.

- ISBN 0-19-518179-4.

- ^ Cohen and Loew 1984.

- ^ "History of nonhuman animal research". Laboratory Primate Advocacy Group. Archived from the original on 13 October 2006.

- PMID 16155644.

- PMID 17106533.

- ^ Costello J (9 June 2011). "The great zoo's who". Irish Independent.

- PMID 11544370.

- S2CID 141344843.

- ISBN 978-0-8160-7364-1

- PMID 9285027.

- PMID 7242665.

- PMID 16614253.

- PMID 4364530.

- ^ S2CID 4260518.

- ^ "History of animal research". www.understandinganimalresearch.org.uk. Retrieved 8 April 2016.

- ^ "Taste of Raspberries, Taste of Death. The 1937 Elixir Sulfanilamide Incident". FDA Consumer magazine. June 1981.

- ^ Burkholz H (1 September 1997). "Giving Thalidomide a Second Chance". FDA Consumer. US Food and Drug Administration.

- ^ ISBN 1-85649-732-1p. 11.

- ^ a b Bernard, Claude An Introduction to the Study of Experimental Medicine, 1865. First English translation by Henry Copley Greene, published by Macmillan & Co., Ltd., 1927; reprinted in 1949, p. 125.

- ISBN 1-85973-330-1.

- ^ a b c "Animal Experimentation: A Student Guide to Balancing the Issues", Australian and New Zealand Council for the Care of Animals in Research and Teaching (ANZCCART), accessed 12 December 2007, cites original reference in Maehle, A-H. and Tr6hler, U. Animal experimentation from antiquity to the end of the eighteenth century: attitudes and arguments. In N. A. Rupke (ed.) Vivisection in Historical Perspective. Croom Helm, London, 1987, p. 22.

- ISBN 0-520-23154-6.

- ^ "In sickness and in health: vivisection's undoing", The Daily Telegraph, November 2003

- ^ LaFollette, H., Shanks, N., Animal Experimentation: the Legacy of Claude Bernard Archived 10 January 2020 at the Wayback Machine, International Studies in the Philosophy of Science (1994) pp. 195–210.

- PMID 1775539.

- ^ Mason, Peter. The Brown Dog Affair Archived 6 October 2020 at the Wayback Machine. Two Sevens Publishing, 1997.

- ^ "The Life and Letters of Charles Darwin, Volume II". Fullbooks.com.

- ISBN 0-393-30930-4.

- ISBN 978-0-9560008-0-4.

- ^ Publications of the Research Defence Society: March 1908–1909; Selected by the committee. London: Macmillan. 1909. p. xiv.

- ^ Buettinger, Craig (1 January 1993) Antivivisection and the charge of zoophil-psychosis in the early twentieth century. The Historian.

- ^ Carbone, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare. Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. nih.gov

- ^ Title 9 – Animals and Animal Products. Code of Federal Regulations. Vol. 1 (1 January 2008).

- ^ a b "Animal Testing and the Law – Animal Legal Defense Fund". Animal Legal Defense Fund. Archived from the original on 23 August 2017. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- ^ Harden G. "USDA Inspector General Audit Report of APHIS Animal Care Program Inspection and Enforcement Activities" (PDF). United States Department of Agriculture Office of Inspector General (Report No. 33601–0001–41). Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- ^ Young R (September 2005). "Audit Report: APHIS Animal Care Program Inspection and Enforcement Activities" (PDF). USDA Office of Inspector General Western Region (Report No. 33002–3–SF). Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- PMID 26486777.

- ^ Carbone, p. 94.

- S2CID 33314019.

- ^ Nandi J (27 April 2012). "Scientists take on activists, want ban on live testing on animals lifted". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 27 October 2012. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- S2CID 196613886.

- ^ a b c d "The Ethics of research involving animals" (PDF). Nuffield Council on Bioethics. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 June 2008.

- ^ "USDA publishes 2016 animal research statistics – 7% rise in animal use". Speaking of Research. 19 June 2017. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g "USDA Statistics for Animals Used in Research in the US". Speaking of Research. 20 March 2008.

- S2CID 46187262. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- ^ Rowan, A., Loew, F., and Weer, J. (1995) "The Animal Research Controversy. Protest, Process and Public Policy: An Analysis of Strategic Issues." Tufts University, North Grafton. cited in Carbone 2004, p. 26.

- ^ Alternatives to Animal Use in Research, Testing and Education, U.S. Congress Office of Technology Assessment, Washington, D.C.:Government Printing Office, 1986, p. 64. In 1966, the Laboratory Animal Breeders Association estimated in testimony before Congress that the number of mice, rats, guinea pigs, hamsters, and rabbits used in 1965 was around 60 million. (Hearings before the Subcommittee on Livestock and Feed Grains, Committee on Agriculture, U.S. House of Representatives, 1966, p. 63.)

- ^ a b "Animal research numbers in 2017". Understanding Animal Research. 2017.

- ^ a b "Home Office Statistics for Animals Used in Research in the UK". Speaking of Research. 23 October 2012.

- ^ OCLC 27347928. Archived from the originalon 27 September 2011. Retrieved 16 August 2013.

- PMID 24987170.

- ^ "2009 CCAC Survey of Animal Use" (PDF). Canadian Council on Animal Care. December 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 June 2015. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- ^ Merkes M, Buttrose R. "New code, same suffering: animals in the lab". ABC. The Drum. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- ^ Even D (29 May 2013). "Number of animal experiments up for first time since 2008". Haaretz. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- ^ "Rise in animal research in South Korea in 2017". Speaking of Research. 20 April 2018. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- ^ "Number of laboratory animals in Germany". Max-Planck-Gesellschaft. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- PMID 20075493.

- S2CID 12923468.

- S2CID 31002250.

- S2CID 21541043.

- S2CID 7395057.

- PMID 15972468.

- ^ PMID 14975532.

- ^ PMID 21829642.

- ^ PMID 17400503.

- PMID 18838673.

- S2CID 10122407.

- ^ S2CID 4472227.

- .

- S2CID 22522876.

- ^ a b c d "Statistics of Scientific Procedures on Living Animals, Great Britain" (PDF). UK Home Office. 2017. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- ^ "Statistics of Scientific Procedures on Living Animals, Great Britain" (PDF). British government. 2004. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- ^ Statistics of Scientific Procedures on Living Animals, Great Britain, 1996 – UK Home Office, Table 13

- ^ "Annual Report Animals" (PDF). Aphis.usda.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 November 2020. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- S2CID 211261775.

- ^ Dog profile, The Humane Society of the United States

- PMID 12388850.

- PMID 23882369.

- ^ "Germany sees 7% rise in animal research procedures in 2016". Speaking of Research. 6 February 2018.

- ^ "France, Italy and the Netherlands publish their 2016 statistics". Speaking of Research. 20 March 2018.

- PMID 33758544.

- PMID 20502460.

- PMID 30643816.

- ^ International Perspectives: The Future of Nonhuman Primate Resources, Proceedings of the Workshop Held 17–19 April, pp. 36–45, 46–48, 63–69, 197–200.

- ^ "Seventh Report on the Statistics on the Number of Animals used for Experimental and other Scientific Purposes in the Member States of the European Union". Report from the Commission to the Council and the European Parliament. 12 May 2013. Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- ^ "U.S. primate import statistics for 2014". International Primate Protection League. Archived from the original on 4 July 2017. Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- ^ a b Kathleen M. Conlee, Erika H. Hoffeld and Martin L. Stephens (2004) Demographic Analysis of Primate Research in the United States, ATLA 32, Supplement 1, 315–22

- ^ St Fleur N (12 June 2015). "U.S. Will Call All Chimps 'Endangered'". The New York Times. The New York Times. Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- S2CID 19980505.

- PMID 11209082.

- PMID 18488016.

- ^ The Royal Society, 2004, p. 1

- ^ PMID 17712221.

- ^ McKie R (2 November 2008). "Ban on primate experiments would be devastating, scientists warn". The Observer. London.

- ^ Invertebrate Animal Resources Archived 25 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine. National Center for Research Resources. ncrr.nih.gov

- ^ "Who's Who of Federal Oversight of Animal Issues". Aesop-project.org. Archived from the original on 22 September 2007.

- S2CID 18872015.

- ^ a b Gillham, Christina (17 February 2006). "Bought to be sold", Newsweek.

- ^ Class B dealers Archived 29 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Humane Society of the United States.

- ^ "Who's Who of Federal Oversight of Animal Issues" Archived 22 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Aesop Project.

- ^ Salinger, Lawrence and Teddlie, Patricia. "Stealing Pets for Research and Profit: The Enforcement (?) of the Animal Welfare Act" Archived 16 January 2013 at archive.today, paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Criminology, Royal York, Toronto, 15 October 2006

- ISBN 0-8217-4951-X.

- ^ Moran, Julio (12 September 1991) "Three Sentenced to Prison for Stealing Pets for Research," L.A. Times.

- ^ Francione, Gary. Animals, Property, and the Law. Temple University Press, 1995, p. 192; Magnuson, Warren G., Chairman. "Opening remarks in hearings prior to enactment of Pub. L. 89-544, the Laboratory Animal Welfare Act," U.S. Senate Committee on Commerce, 25 March 1966.

- ^ Notorious Animal Dealer Loses License and Pays Record Fine, The Humane Society of the United States

- ^ Animal Testing: Where Do the Animals Come From?. American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. According to the ASPCA, the following states prohibit shelters from providing animals for research: Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Vermont, and West Virginia.

- ^ "Council Directive 86/609/EEC of 24 November 1986". Eur-lex.europa.eu. 24 November 1986.

- ^ "Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 September 2010 on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes Text with EEA relevance". Eur-lex.europa.eu. 22 September 2010.

- ^ Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) Archived 31 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs

- ^ a b ""Statistics of Scientific Procedures on Living Animals", Statistics of Scientific Procedures on Living Animals, Home Office" (PDF). 2004. p. 87.

- ^ U.S. Primate Imports Spike International Primate Protection League April 2007

- PMID 1808195.

- PMID 1808193.

- ^ Carbone, p. 149.

- ^ Rollin drafted the 1985 Health Research Extension Act and an animal welfare amendment to the 1985 Food Security Act: see Rollin, Bernard. "Animal research: a moral science. Talking Point on the use of animals in scientific research", EMBO Reports 8, 6, 2007, pp. 521–25

- ^ a b Rollin, Bernard. The Unheeded Cry: Animal Consciousness, Animal Pain, and Science. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. xii, 117–18, cited in Carbone 2004, p. 150.

- S2CID 8650837.

- PMID 9464883.

- ^ "Smarter Than You Think: Renowned Canine Researcher Puts Dogs' Intelligence on Par with 2-Year-Old Human". www.apa.org. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- ^ "Animal Welfare Act 1999". Parliamentary Counsel Office. 2015. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- ^ "Norwegian animal welfare act". Animal Legal and Historical Center. 2011. Retrieved 25 January 2016.

- ISBN 0-309-05377-3.

- ^ "How to Work With Your Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC)". ori.hhs.gov.

- PMID 38003070.

- ISSN 0952-8369.

- PMID 30970545.

- ^ PMID 12098013.

- ^ Animal Procedures Committee: review of cost-benefit assessment in the use of animals in research Archived 27 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine The Animal Procedures Committee, June 2003 p46-7

- ^ Carbone, Larry. "Euthanasia," in Bekoff, M. and Meaney, C. Encyclopedia of Animal Rights and Welfare. Greenwood Publishing Group, pp. 164–66, cited in Carbone 2004, pp. 189–90.

- ^ Cooper D (11 June 2017). ""Euthanasia Guidelines", Research animal resources". University of Minnesota.

- PMID 8938617.

- ISBN 0-309-05377-3.

- S2CID 51865025.

- ^ "AVMA Guidelines on Euthanasia, June 2007 edition, Report of the AVMA Panel on Euthanasia" (PDF). Avma.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 August 2011.

- ^ a b "Select Committee on Animals in Scientific Procedures Report", House of Lords, 16 July 2002. See chapter 3: "The purpose and nature of animal experiments." Retrieved 6 July 2010.

- ^ PMID 15025339.

- S2CID 21184903.

- PMID 14761310.

- S2CID 23492348.

- PMID 8577843.

- PMID 10203825.

- PMID 18050439.

- .

- ISBN 0-12-473070-1[page needed]

- ^ For example "in addition to providing the chimpanzees with enrichment, the termite mound is also the focal point of a tool-use study being conducted", from the web page of the Lincoln Park Zoo. Retrieved 25 April 2007.

- The Jackson Laboratory. Retrieved 30 January 2008.

- PMID 16252286.

- S2CID 4304296.

- PMID 17712222.

- PMID 15787657.

- PMID 17401426.

- S2CID 6490409.

- PMID 16678276.

- S2CID 32489790.

- ^ PMID 10480640.

- PMID 14988196.

- ^ Langley, Gill (2006) next of kin...A report on the use of primates in experiments Archived 27 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine, BUAV.

- ^ The History of Deep Brain Stimulation Archived 31 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine. parkinsonsappeal.com

- S2CID 72941995.

- ^ PMID 17981539.

- PMID 16131605.

- S2CID 22668776.

- ^ Townsend, Mark (20 April 2003). "Exposed: secrets of the animal organ lab" Archived 6 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine, The Guardian.

- ^ Curtis, Polly (11 July 2003). "Home Office under renewed fire in animal rights row", The Guardian.

- ^ BUAV

- ^ Fifth Report on the Statistics on the Number of Animals used for Experimental and other Scientific Purposes in the Member States of the European Union, Commission of the European Communities, published November 2007

- ^ S2CID 4422086. Archived from the original(PDF) on 27 February 2008.

- PMID 2760837.

- PMID 2336839.

- ^ "Testing of chemicals – OECD". www.oecd.org. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- PMID 9599698.

- ^ Inter-Governmental Organization Eliminates the LD50 Test, The Humane Society of the United States (2003-02-05)

- ^ "OECD guideline 405, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2008. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- ^ Species Used in Research: Rabbit, Humane Society of the United States

- PMID 11425356.

- S2CID 24972694.

- ^ a b Draize rabbit eye test replacement milestone welcomed. Dr Hadwen Trust (2009-09-21)

- ^ Toxicity Testing for Assessment of Environmental Agents" National Academies Press, (2006), p. 21.

- S2CID 851143.

- ^ "Where is the toxicology for the twenty-first century?". Pro-Test Italia. 2013. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- PMID 11395155.

- PMID 3051142.

- PMID 26018957.

- PMID 27653274.

- ^ Stephens, Martin & Rowan, Andrew. An overview of Animal Testing Issues, Humane Society of the United States

- ^ "Cosmetics animal testing in the EU". Archived from the original on 30 December 2020. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- ^ Engebretson, Monica (16 March 2014). "India Joins the EU and Israel in Surpassing the US in Cruelty-Free Cosmetics Testing Policy". The World Post.

- ^ "Cruelty Free International Applauds Congressman Jim Moran for Bill to End Cosmetics Testing on Animals in the United States" (Press release). 5 March 2014. Archived from the original on 18 March 2014.

- ^ Fox, Stacy (10 March 2014). "Animal Attraction: Federal Bill to End Cosmetics Testing on Animals Introduced in Congress" (Press release). Humane Society of the United States. Archived from the original on 11 March 2014.

- ^ a b Osborn, Andrew & Gentleman, Amelia."Secret French move to block animal-testing ban", The Guardian (19 August 2003). Retrieved 27 February 2008.

- ^ Mohan V (14 October 2014). "India bans import of cosmetics tested on animals". The Times of India. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- ^ "EU Directive 2001/83/EC, p. 44". Eur-lex.europa.eu.

- ^ "EU Directive 2001/83/EC, p. 45". Eur-lex.europa.eu.

- PMID 17199490.

- ISBN 978-0-313-32390-4.

- ISBN 978-0-19-511908-4.

- ^ Downey M (25 June 2013). "Should students dissect animals or should schools move to virtual dissections?". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- ^ Pulla P (6 August 2014). "Dissections banned in Indian universities". Science. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- ^ Shine N. "The Battle Over High School Animal Dissection". Pacific Standard. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- ^ "Invertebrates in Education and Conservation Conference | Department of Neuroscience". Neurosci.arizona.edu. Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- ^ Dalal R, Even M, Sandusky C, Barnard N (August 2005). "Replacement Alternatives in Education: Animal-Free Teaching" (Abstract from Fifth World Congress on Alternatives and Animal Use in the Life Sciences, Berlin). The Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine. Archived from the original on 22 July 2014. Retrieved 9 April 2015.

- ^ "The NORINA database of alternatives". Oslovet.norecopa.no. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- ^ "Welcome". Interniche.org. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- ^ a b "Row over US mobile phone 'cockroach backpack' app". BBC News. 9 November 2013. Retrieved 9 November 2013.

- ^ Hamilton, Anita (1 November 2013). "Resistance is Futile: PETA Attempts to Halt the Sale of Remote-Controlled Cyborg Cockroaches". Time. Retrieved 10 November 2013.

- ^ Brook, Tom Vanden, "Brain Study, Animal Rights Collide", USA Today (7 April 2009), p. 1.

- ^ a b Kelly J (7 March 2013). "Who, What, Why: Does shooting goats save soldiers' lives?". BBC News Magazine.

- ^ Londoño E (24 February 2013). "Military is required to justify using animals in medic training after pressure from activists". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 15 December 2013.

- ^ Vergakis B (14 February 2014). "Coast Guard reduces use of live animals in training". Archived from the original on 9 July 2015. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- ^ Bender B (12 November 2014). "Military to curtail use of live animals in medical training". Boston Globe. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- ^ Champaco B (15 August 2013). "PETA: Madigan Army Medical Center Has Stopped 'Cruel' Ferret-Testing". Patch. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- ISBN 0-309-07878-4.

- ^ Cooper, Sylvia (1 August 1999). "Pets crowd animal shelter" Archived 2 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine, The Augusta Chronicle.

- National Research Council of the National Academies2004, p. 2

- ^ "About". Peta.org. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- ^ "UK Legislation: A Criticism" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 June 2008. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection. Archived from the original(PDF) on 13 May 2015. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- ^ "Biomedical Research: The Humane Society of the United States". Humanesociety.org. Archived from the original on 30 September 2020. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- ^ "Animal Testing and Animal Experimentation Issues | Physicians Committee". Pcrm.org. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- S2CID 18620094. Archived from the original(PDF) on 8 October 2020. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- ^ Riffkin R (18 May 2015). "In U.S., More Say Animals Should Have Same Rights as People". Gallup. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- ^ Funk C, Rainie L (29 January 2015). "Public and Scientists' Views on Science and Society". Pew Research Center. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- ^ Singer, Peter (ed.). "A Companion to Ethics". Blackwell Companions to Philosophy, 1991.

- ^ a b Chapter 14, Discussion of ethical issues, p . 244 Archived 28 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine in: The ethics of research involving animals Archived 29 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine at the Nuffield Council on Bioethics. Published 25 May 2005

- ^ George R. "Donald Watson 2002 Unabridged Interview" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 October 2019.

- ISBN 0-631-23019-X.

- PMID 12782533.

- PMID 18635842.

- PMID 17204689.

- PMID 24906117.

- PMID 20361020.

- S2CID 11500691.

- S2CID 9892510.

- ^ St Fleur N (12 June 2015). "U.S. Will Call All Chimps 'Endangered'". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- ^ Kaiser J (26 June 2013). "NIH Will Retire Most Research Chimps, End Many Projects". sciencemag.org. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- ^ "Summary of House of Lords Select Committee on Animals in Scientific Procedures". UK Parliament. 24 July 2002. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- ^ 韓国・食薬庁で「実験動物慰霊祭」挙行 Archived 29 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- S2CID 26159256.

- PMID 5921536.

- PMID 3872938.

- S2CID 3477585.

- ISBN 978-0-7817-3061-7.

- ^ Franklin, Ben A. (30 August 1987) "Going to Extremes for 'Animal Rights'", The New York Times.

- PMID 3952503.

- ^ Laville, Sandra (8 February 2005). "Lab monkeys 'scream with fear' in tests", The Guardian.

- ^ "Columbia in animal cruelty dispute", CNN (2003-10-12)

- ^ Benz, Kathy and McManus, Michael (17 May 2005). PETA accuses lab of animal cruelty, CNN.

- ^ Scott, Luci (1 April 2006). "Probe leads to Covance fine", The Arizona Republic. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- S2CID 8006958.

- PMID 17021020.

- ^ Epstein, David (22 August 2006). Throwing in the Towel Archived 27 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Inside Higher Education

- ^ Predators Unleashed, Investor's Business Daily (2006-08-24)

- ^ McDonald, Patrick Range (8 August 2007). UCLA Monkey Madness, LA Weekly.

- ^ "It's a Dog's Life", Countryside Undercover, Channel Four Television, UK (26 March 1997).

- ^ "It's a dog's life" Archived 8 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Small World Productions (2005). Retrieved 6 July 2010.

- ^ "A controversial laboratory". BBC News. 18 January 2001. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- ^ Broughton, Zoe (March 2001). "Seeing Is Believing – cruelty to dogs at Huntingdon Life Sciences", The Ecologist.

- ^ "From push to shove" Archived 22 November 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Southern Poverty Law Group Intelligence Report, Fall 2002

- ^ Lewis, John E. "Statement of John Lewis", US Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works, 26 October 2005, accessed 17 January 2011.

- ^ Evers, Marco. "Resisting the Animal Avengers", Part 1, Part 2, Der Spiegel, 19 November 2007.

- ^ Weaver, Matthew. "Animal rights activists jailed for terrorising suppliers to Huntingdon Life Sciences", The Guardian, 25 October 2010.

- ^ Herbert, Ian (27 January 2007). "Collapse in support for animal rights extremist attacks", The Independent.

- PMID 18474018.

- ^ PMID 23372426.

- ^ PMID 19297654.

- PMID 14988196.

- PMID 17175568.

- S2CID 34932997.

- PMID 34129637.

- ^ "White Coat Waste Project". Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- ^ "Should dogs be guinea pigs in government research? A bipartisan group says no". The Washington Post. 15 November 2016.

- ^ "WCW EXPOSÉ: FAUCI SPENT $424K ON BEAGLE EXPERIMENTS, DOGS BITTEN TO DEATH BY FLIES". 30 July 2021.

- ^ "PETA calls for Dr. Fauci to resign: 'Our position is clear'". Fox News. 5 November 2021.

- ^ "Experimenters Fed Puppies' Heads to Infected Flies, but That's Not All Fauci's NIH Funded". 25 October 2021.

- ^ "What are the 3Rs?". NC3Rs. Archived from the original on 1 August 2014. Retrieved 16 December 2018.

- PMID 12513669.

- S2CID 25015151.

- PMID 14671703.

- PMID 29466319.

- ^ "Alternatives to Animal Testing | Animals Used for Experimentation | The Issues". Peta.org. 21 June 2010. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- ^ Rhodes M (28 May 2015). "Inside L'Oreal's Plan to 3-D Print Human Skin". Wired. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- PMID 17255608.

- PMID 20836040.

- ^ "Microdosing". 3Rs. Canadian Council on Animal Care in Science. Archived from the original on 7 June 2015. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- ^ "What Is A PET Scan? How Does A PET Scan Work?". Medicalnewstoday.com. 23 June 2017.

- PMID 19918375.

- ^ McNeil D (13 January 2014). "PETA's Donation to Help Save Lives, Animal and Human". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- ^ Bernstein F (4 October 2005). "An On-Screen Alternative to Hands-On Dissection". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- ^ "NTP Interagency Center for the Evaluation of Alternative Toxicological Methods – NTP". Iccvam.niehs.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 9 December 2013. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- ^ ZEBET database on alternatives to animal experiments on the Internet (AnimAlt-ZEBET). BfR (30 September 2004). Retrieved on 2013-01-21.

- ^ About JaCVAM-Organization of JaCVAM Archived 11 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Jacvam.jp. Retrieved on 2013-01-21.

- ^ EPAA – Home Archived 1 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Ec.europa.eu. Retrieved on 2013-01-21.

- ^ ecopa – european consensus-platform for alternatives. Ecopa.eu. Retrieved on 2013-01-21.

- ^ Center for Alternatives to Animal Testing – Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Caat.jhsph.edu. Retrieved on 2013-01-21.

- ^ "NC3Rs". NC3Rs.org.uk. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

Works cited

- Carbone L (2004). What animals want: expertise and advocacy in laboratory animal welfare policy. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. OCLC 57138138.

Further reading

- Conn, P. Michael and Parker, James V (2008). The Animal Research War, Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 978-0-230-60014-0

- Guerrini, Anita (2003). Experimenting with humans and animals: from Galen to animal rights. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-7197-9.

- 15 Companies That Still Test on Animals in 2022. Yahoo! Finance. January 9, 2023.

External links

Media related to Animal testing at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Animal testing at Wikimedia Commons Quotations related to Animal testing at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Animal testing at Wikiquote