Ankle

| Ankle | |

|---|---|

Human ankle | |

Lateral view of the human ankle | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | tarsus |

| MeSH | D000842 |

| TA98 | A01.1.00.041 |

| TA2 | 165 |

| FMA | 9665 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The ankle, the talocrural region

The main bones of the ankle region are the talus (in the foot), and the tibia and fibula (in the leg). The talocrural joint is a synovial hinge joint that connects the distal ends of the tibia and fibula in the lower limb with the proximal end of the talus.[7] The articulation between the tibia and the talus bears more weight than that between the smaller fibula and the talus.

Structure

Region

The ankle region is found at the junction of the leg and the foot. It extends downwards (distally) from the narrowest point of the lower leg and includes the parts of the foot closer to the body (proximal) to the heel and upper surface (dorsum) of the foot.[8]: 768

Ankle joint

The talocrural joint is the only mortise and tenon joint in the human body,

Because the motion of the subtalar joint provides a significant contribution to positioning the foot, some authors will describe it as the lower ankle joint, and call the talocrural joint the upper ankle joint.[11] Dorsiflexion and Plantarflexion are the movements that take place in the ankle joint. When the foot is plantar flexed, the ankle joint also allows some movements of side to side gliding, rotation, adduction, and abduction.[12]

The bony arch formed by the tibial plafond and the two malleoli is referred to as the ankle "mortise" (or talar mortise). The mortise is a rectangular socket.[1] The ankle is composed of three joints: the talocrural joint (also called talotibial joint, tibiotalar joint, talar mortise, talar joint), the subtalar joint (also called talocalcaneal), and the Inferior tibiofibular joint.[3][4][5] The joint surface of all bones in the ankle are covered with articular cartilage.

The distances between the bones in the ankle are as follows:[13]

- Talus - medial malleolus : 1.70 ± 0.13 mm

- Talus - tibial plafond: 2.04 ± 0.29 mm

- Talus - lateral malleolus: 2.13 ± 0.20 mm

Decreased distances indicate osteoarthritis.

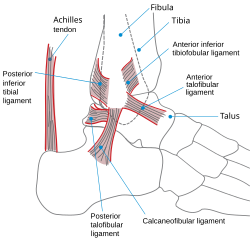

Ligaments

The ankle joint is bound by the strong deltoid ligament and three lateral ligaments: the anterior talofibular ligament, the posterior talofibular ligament, and the calcaneofibular ligament.

- The deltoid ligament supports the medial side of the joint, and is attached at the navicular tuberosity, and to the medial surface of the talus.

- The anterior and posterior talofibular ligaments support the lateral side of the joint from the lateral malleolusof the fibula to the dorsal and ventral ends of the talus.

- The calcaneofibular ligament is attached at the lateral malleolus and to the lateral surface of the calcaneus.

Though it does not span the ankle joint itself, the syndesmotic ligament makes an important contribution to the stability of the ankle. This ligament spans the syndesmosis, i.e. the articulation between the medial aspect of the distal fibula and the lateral aspect of the distal tibia. An isolated injury to this ligament is often called a high ankle sprain.

The bony architecture of the ankle joint is most stable in

Retinacula, tendons and their synovial sheaths, vessels, and nerves

A number of tendons pass through the ankle region. Bands of connective tissue called retinacula (singular: retinaculum) allow the tendons to exert force across the angle between the leg and foot without lifting away from the angle, a process called bowstringing.[11] The

The flexor retinaculum of foot extends from the medial malleolus to the medical process of the calcaneus, and the following structures in order from medial to lateral: the tendon of the tibialis posterior muscle, the tendon of the flexor digitorum longus muscle, the posterior tibial artery and vein, the tibial nerve, and the tendon of the flexor hallucis longus muscle.

The

Mechanoreceptors

Mechanoreceptors of the ankle send proprioceptive sensory input to the central nervous system (CNS).[15] Muscle spindles are thought to be the main type of mechanoreceptor responsible for proprioceptive attributes from the ankle.[16] The muscle spindle gives feedback to the CNS system on the current length of the muscle it innervates and to any change in length that occurs.

It was hypothesized that muscle spindle feedback from the ankle dorsiflexors played the most substantial role in proprioception relative to other muscular receptors that cross at the ankle joint. However, due to the multi-planar range of motion at the ankle joint there is not one group of muscles that is responsible for this.[17] This helps to explain the relationship between the ankle and balance.

In 2011, a relationship between proprioception of the ankle and balance performance was seen in the CNS. This was done by using a fMRI machine in order to see the changes in brain activity when the receptors of the ankle are stimulated.[18] This implicates the ankle directly with the ability to balance. Further research is needed in order to see to what extent does the ankle affect balance.

Function

Historically, the role of the ankle in locomotion has been discussed by Aristotle and Leonardo da Vinci. There is no question that ankle push-off is a significant force in human gait, but how much energy is used in leg swing as opposed to advancing the whole-body center of mass is not clear.[19]

Clinical significance

Traumatic injury

Of all major joints, the ankle is the most commonly injured. If the outside surface of the foot is twisted under the leg during weight bearing, the

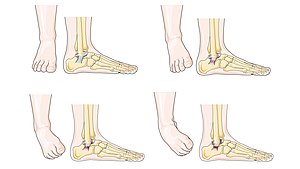

Fractures

An

Ankle fractures may result from excessive stress on the joint such as from rolling an ankle or from

Treatment depends on the fracture type. Ankle stability largely dictates non-operative vs. operative treatment. Non-operative treatment includes splinting or casting while operative treatment includes fixing the fracture with metal implants through an open reduction internal fixation (

Imaging

The initial evaluation of suspected ankle pathology is usually by projectional radiography ("X-ray").

Varus or valgus deformity, if suspected, can be measured with the frontal tibiotalar surface angle (TTS), formed by the mid-longitudinal tibial axis (such as through a line bisecting the tibia at 8 and 13 cm above the tibial plafond) and the talar surface.[24] An angle of less than 84 degrees is regarded as talipes varus, and an angle of more than 94 degrees is regarded as talipes valgus.[25]

For ligamentous injury, there are three main landmarks on X-rays: The first is the tibiofibular clear space, the horizontal distance from the lateral border of the posterior tibial malleolus to the medial border of the fibula, with greater than 5 mm being abnormal. The second is tibiofibular overlap, the horizontal distance between the medial border of the fibula and the lateral border of the anterior tibial prominence, with less than 10 mm being abnormal. The final measurement is the medial clear space, the distance between the lateral aspect of the medial malleolus and the medial border of the talus at the level of the talar dome, with a measurement greater than 4 mm being abnormal. Loss of any of these normal anatomic spaces can indirectly reflect ligamentous injury or occult fracture, and can be followed by MRI or CT.[26]

Abnormalities

Clubfoot or talipes equinovarus, which occurs in one to two of every 1,000 live births, involves multiple abnormalities of the foot.[27] Equinus refers to the downard deflection of the ankle, and is named for the walking on the toes in the manner of a horse.[28] This does not occur because it is accompanied by an inward rotation of the foot (varus deformity), which untreated, results in walking on the sides of the feet. Treatment may involve manipulation and casting or surgery.[27]

Ankle joint equinus, normally in adults, relates to restricted ankle joint range of motion(ROM).[29] Calf muscle stretching exercises are normally helpful to increase the ankle joint dorsiflexion and used to manage clinical symptoms resulting from ankle equinus.[30]

Occasionally a human ankle has a ball-and-socket ankle joint and fusion of the talo-navicular joint.[31]

History

The word ankle or ancle is common, in various forms, to

Other animals

Evolution

It has been suggested that dexterous control of toes has been lost in favour of a more precise voluntary control of the ankle joint.[33]

See also

Footnotes

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4511-1945-9.

- ISBN 978-0-544-18897-6.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-683-30663-7.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-443-10351-3.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4557-3394-1.

- ^ Gray, Henry (1918). "Talocrural Articulation or Ankle-joint". Anatomy of the Human Body.

- ISBN 978-0-544-18897-6.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4963-4721-3.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7020-6851-5.

- ISBN 978-1-4511-6144-1.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-323-39935-7.

- ^ Joseph H Volker (2018-08-08). "Ankle Joint". Earth's Lab.

- PMID 26146520.

- ^ Gatt, A. and Chockalingam, N., 2011. Clinical Assessment of Ankle Joint DorsiflexionA Review of Measurement Techniques. Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association, 101(1), pp.59-69.https://doi.org/10.7547/1010059

- PMID 7706334.

- S2CID 13099542.

- S2CID 14626459.

- PMID 22072686.

- PMID 27903626.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Ankle Fractures (Broken Ankle) - OrthoInfo - AAOS". www.orthoinfo.org. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ PMID 31194464.

- PMID 27033333.

- ISSN 2667-3967.

- PMID 22609967.

- ISBN 9789463750479.

- PMID 17106502.

- ^ PMID 14989573.

- ISBN 978-3-319-01471-5.

- PMID 21242472.

- PMID 21944945.

- PMID 6490876.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 2 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 58.

- S2CID 24650165.

References

- Anderson, Stephen A.; Calais-Germain, Blandine (1993). Anatomy of Movement. Chicago: Eastland Press. ISBN 978-0-939616-17-6.

- McKinley, Michael P.; Martini, Frederic; Timmons, Michael J. (2000). Human Anatomy. Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-010011-5.

- Marieb, Elaine Nicpon (2000). Essentials of Human Anatomy and Physiology. San Francisco: Benjamin Cummings. ISBN 978-0-8053-4940-5.

Additional images

-

Dorsum of Foot. Ankle joint. Deep dissection.

-

Dorsum of Foot. Ankle joint. Deep dissection.

-

Ankle joint. Deep dissection. Anterior view.

-

Dorsum of Foot. Ankle joint. Deep dissection.

External links

- Ardizzone, Remy; Valmassy, Ronald L. (October 2005). "How To Diagnose Lateral Ankle Injuries". Podiatry Today. Archived from the original on January 4, 2010. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- Haddad, Steven L. (ed.). "Foot & Ankle". Your orthopaedic connection (American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons). Archived from the original on 23 March 2010. Retrieved September 21, 2017.