Antarctica

| |

| Area | 14,200,000 km2 5,500,000 sq mi[1] |

|---|---|

| Population | 1,300 to 5,100 (seasonal) |

| Population density | 0.00009/km2 to 0.00036/km2 (seasonal) |

| Countries | 7 territorial claims |

| Time zones | All time zones |

| Internet TLD | .aq |

| Largest settlements | |

| UN M49 code | 010 |

Antarctica (

Antarctica is, on average, the coldest, driest, and windiest of the continents, and it has the highest average

The

Antarctica is

Etymology

The name given to the continent originates from the word antarctic, which comes from Middle French antartique or antarctique ('opposite to the Arctic') and, in turn, the Latin antarcticus ('opposite to the north'). Antarcticus is derived from the Greek ἀντι- ('anti-') and ἀρκτικός ('of the Bear', 'northern').[5] The Greek philosopher Aristotle wrote in Meteorology about an "Antarctic region" in c. 350 BCE.[6] The Greek geographer Marinus of Tyre reportedly used the name in his world map from the second century CE, now lost. The Roman authors Gaius Julius Hyginus and Apuleius used for the South Pole the romanised Greek name polus antarcticus,[7] from which derived the Old French pole antartike (modern pôle antarctique) attested in 1270, and from there the Middle English pol antartik, found first in a treatise written by the English author Geoffrey Chaucer.[5]

Belief by Europeans in the existence of a Terra Australis—a vast continent in the far south of the globe to balance the northern lands of Europe, Asia, and North Africa—had existed as an intellectual concept since classical antiquity. The belief in such a land lasted until the European discovery of Australia.[8]

During the early 19th century, explorer Matthew Flinders doubted the existence of a detached continent south of Australia (then called New Holland) and thus advocated for the "Terra Australis" name to be used for Australia instead.[9][10] In 1824, the colonial authorities in Sydney officially renamed the continent of New Holland to Australia, leaving the term "Terra Australis" unavailable as a reference to Antarctica. Over the following decades, geographers used phrases such as "the Antarctic Continent". They searched for a more poetic replacement, suggesting names such as Ultima and Antipodea.[11] Antarctica was adopted in the 1890s, with the first use of the name being attributed to the Scottish cartographer John George Bartholomew.[12]

Geography

Positioned asymmetrically around the South Pole and largely south of the

The

Antarctica is divided into

East Antarctica comprises Coats Land, Queen Maud Land, Enderby Land, Mac. Robertson Land, Wilkes Land, and Victoria Land. All but a small portion of the region lies within the Eastern Hemisphere. East Antarctica is largely covered by the East Antarctic Ice Sheet.[22] There are numerous islands surrounding Antarctica, most of which are volcanic and very young by geological standards.[23] The most prominent exceptions to this are the islands of the Kerguelen Plateau, the earliest of which formed around 40 Ma.[23][24]

Geologic history

From the end of the Neoproterozoic era to the Cretaceous, Antarctica was part of the supercontinent Gondwana.[29] Modern Antarctica was formed as Gondwana gradually broke apart beginning around 183 Ma.[30] For a large proportion of the Phanerozoic, Antarctica had a tropical or temperate climate, and it was covered in forests.[31]

Palaeozoic era (540–250 Ma)

During the

Antarctica became glaciated during the

Mesozoic era (250–66 Ma)

The continued warming dried out much of Gondwana. During the Triassic, Antarctica was dominated by

The

Gondwana breakup (160–15 Ma)

Africa separated from Antarctica in the Jurassic around 160 Ma, followed by the Indian subcontinent in the early Cretaceous (about 125 Ma).[48] During the early Paleogene, Antarctica remained connected to South America as well as to southeastern Australia. Fauna from the La Meseta Formation in the Antarctic Peninsula, dating to the Eocene, is very similar to equivalent South American faunas; with marsupials, xenarthrans, litoptern, and astrapotherian ungulates, as well as gondwanatheres and possibly meridiolestidans.[49][50] Marsupials are thought to have dispersed into Australia via Antarctica by the early Eocene.[51]

Around 53 Ma, Australia-

Present day

The geology of Antarctica, largely obscured by the continental ice sheet,[56] is being revealed by techniques such as remote sensing, ground-penetrating radar, and satellite imagery.[57] Geologically, West Antarctica closely resembles the South American Andes.[58] The Antarctic Peninsula was formed by geologic uplift and the transformation of sea bed sediments into metamorphic rocks.[59]

West Antarctica was formed by the merging of several

East Antarctica is geologically varied. Its formation began during the Archean Eon (4,000 Ma–2,500 Ma), and stopped during the Cambrian Period.[61] It is built on a craton of rock, which is the basis of the Precambrian Shield.[62] On top of the base are coal and sandstones, limestones, and shales that were laid down during the Devonian and Jurassic periods to form the Transantarctic Mountains.[63] In coastal areas such as the Shackleton Range and Victoria Land, some faulting has occurred.[64][65]

Coal was first recorded in Antarctica near the

Climate

Antarctica is the coldest, windiest, and driest of Earth's continents.[1] Near the coast, the temperature can exceed 10 °C in summer and fall to below −40 °C in winter. Over the elevated inland, it can rise to about −30 °C in summer but fall below −80 °C in winter.

The lowest natural air temperature ever recorded on Earth was −89.2 °C (−128.6 °F) at the Russian Vostok Station in Antarctica on 21 July 1983.[69] A lower air temperature of −94.7 °C (−138.5 °F) was recorded in 2010 by satellite—however, it may have been influenced by ground temperatures and was not recorded at a height of 2 m (7 ft) above the surface as required for official air temperature records.[70][71]

Antarctica is a

Regional differences

East Antarctica is colder than its western counterpart because of its higher elevation.

Climate change

Climate change caused by greenhouse gas emissions from human activities occurs everywhere on Earth, and while Antarctica is less vulnerable to it than any other continent,[77] climate change in Antarctica has already been observed. There has been an average temperature increase of >0.05 °C/decade since 1957 across the continent, although it had been uneven.[78] While West Antarctica warmed by over 0.1 °C/decade from the 1950s to the 2000s and the exposed Antarctic Peninsula has warmed by 3 °C (5.4 °F) since the mid-20th century,[79] the colder and more stable East Antarctica had been experiencing cooling until the 2000s.[80][81] Around Antarctica, the Southern Ocean has absorbed more heat than any other ocean,[82] with particularly strong warming at depths below 2,000 m (6,600 ft)[83]: 1230 and around the West Antarctic, which has warmed by 1 °C (1.8 °F) since 1955.[79]

The warming of Antarctica's territorial waters has caused the weakening or outright collapse of

The fresh

Ozone depletion

Scientists have studied the

The ozone depletion can cause a cooling of around 6 °C (11 °F) in the stratosphere. The cooling strengthens the polar vortex and so prevents the outflow of the cold air near the South Pole, which in turn cools the continental mass of the East Antarctic ice sheet. The peripheral areas of Antarctica, especially the Antarctic Peninsula, are then subjected to higher temperatures, which accelerate the melting of the ice.[102] Models suggest that ozone depletion and the enhanced polar vortex effect may also account for the period of increasing sea ice extent, lasting from when observation started in the late 1970s until 2014. Since then, the coverage of Antarctic sea ice has decreased rapidly.[108][109]

Biodiversity

Most species in Antarctica seem to be the descendants of species that lived there millions of years ago. As such, they must have survived multiple

Animals

Invertebrate life of Antarctica includes species of microscopic

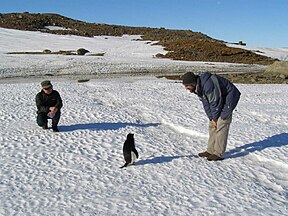

Antarctic krill, which congregates in large schools, is the keystone species of the ecosystem of the Southern Ocean, being an important food organism for whales, seals, leopard seals, fur seals, squid, icefish, and many bird species, such as penguins and albatrosses.[113] Some species of marine animals exist and rely, directly or indirectly, on phytoplankton. Antarctic sea life includes penguins, blue whales, orcas, colossal squids and fur seals.[114] The Antarctic fur seal was very heavily hunted in the 18th and 19th centuries for its pelt by seal hunters from the United States and the United Kingdom.[115] Leopard seals are apex predators in the Antarctic ecosystem and migrate across the Southern Ocean in search of food.[116]

There are approximately 40 bird species that breed on or close to Antarctica, including species of

A

Fungi

About 1,150 species of fungi have been recorded in the Antarctic region, of which about 750 are non-lichen-forming.[119][120] Some of the species, having evolved under extreme conditions, have colonised structural cavities within porous rocks and have contributed to shaping the rock formations of the McMurdo Dry Valleys and surrounding mountain ridges.[121]

The simplified

The same features can be observed in algae and cyanobacteria, suggesting that they are adaptations to the conditions prevailing in Antarctica. This has led to speculation that life on Mars might have been similar to Antarctic fungi, such as Cryomyces antarcticus and Cryomyces minteri.[121] Some of the species of fungi, which are apparently endemic to Antarctica, live in bird dung, and have evolved so they can grow inside extremely cold dung, but can also pass through the intestines of warm-blooded animals.[123][124]

Plants

Throughout its history, Antarctica has seen a wide variety of plant life. In the Cretaceous, it was dominated by a fern-conifer ecosystem, which changed into a temperate rainforest by the end of that period. During the colder Neogene (17–2.5 Ma), a tundra ecosystem replaced the rainforests. The climate of present-day Antarctica does not allow extensive vegetation to form.[125] A combination of freezing temperatures, poor soil quality, and a lack of moisture and sunlight inhibit plant growth, causing low species diversity and limited distribution. The flora largely consists of bryophytes (25 species of liverworts and 100 species of mosses). There are three species of flowering plants, all of which are found in the Antarctic Peninsula: Deschampsia antarctica (Antarctic hair grass), Colobanthus quitensis (Antarctic pearlwort) and the non-native Poa annua (annual bluegrass).[126]

Other organisms

Of the 700 species of algae in Antarctica, around half are marine phytoplankton. Multicoloured snow algae are especially abundant in the coastal regions during the summer.[127] Even sea ice can harbour unique ecological communities, as it expels all salt from the water when it freezes, which accumulates into pockets of brine that also harbour dormant microorganisms. When the ice begins to melt, brine pockets expand and can combine to form brine channels, and the algae inside the pockets can reawaken and thrive until the next freeze.[128][129] Bacteria have also been found as deep as 800 m (0.50 mi) under the ice.[130] It is thought to be likely that there exists a native bacterial community within the subterranean water body of Lake Vostok.[131] The existence of life there is thought to strengthen the argument for the possibility of life on Jupiter's moon Europa, which may have water beneath its water-ice crust.[132] There exists a community of extremophile bacteria in the highly alkaline waters of Lake Untersee.[133][134] The prevalence of highly resilient creatures in such inhospitable areas could further bolster the argument for extraterrestrial life in cold, methane-rich environments.[135]

Conservation and environmental protection

The first international agreement to protect Antarctica's biodiversity was adopted in 1964.[136] The overfishing of krill (an animal that plays a large role in the Antarctic ecosystem) led officials to enact regulations on fishing. The Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources, an international treaty that came into force in 1980, regulates fisheries, aiming to preserve ecological relationships.[1] Despite these regulations, illegal fishing—particularly of the highly prized Patagonian toothfish which is marketed as Chilean sea bass in the U.S.—remains a problem.[137]

In analogy to the 1980 treaty on

The pressure group

Despite these protections, the biodiversity in Antarctica is still at risk from human activities.

History of exploration

Early world maps, like the 1513 Piri Reis map, feature the hypothetical continent Terra Australis. Much larger than and unrelated to Antarctica, Terra Australis was a landmass that classical scholars presumed necessary to balance the known lands in the northern hemisphere.[144]

19th century

Sealers were among the earliest to go closer to the Antarctic landmass, perhaps in the earlier part of the 19th century. The oldest known human remains in the Antarctic region was a skull, dated from 1819 to 1825, that belonged to a young woman on Yamana Beach at the South Shetland Islands. The woman, who was likely to have been part of a sealing expedition, was found in 1985.[148]

The first person to see Antarctica or its ice shelf was long thought to have been the British sailor Edward Bransfield, a captain in the Royal Navy, who discovered the tip of the Antarctic peninsula on 30 January 1820. However, a captain in the Imperial Russian Navy, Fabian Gottlieb von Bellingshausen, recorded seeing an ice shelf on 27 January.[149] The American sealer Nathaniel Palmer, whose sealing ship was in the region at this time, may also have been the first to sight the Antarctic Peninsula.[150]

The

On 22 January 1840, two days after the discovery of the coast west of the Balleny Islands, some members of the crew of the 1837–1840 expedition of the French explorer Jules Dumont d'Urville disembarked on the Dumoulin Islands, off the coast of Adélie Land, where they took some mineral, algae, and animal samples, erected the French flag, and claimed French sovereignty over the territory.[155] The American captain Charles Wilkes led an expedition in 1838–1839 and was the first to claim he had discovered the continent.[156] The British naval officer James Clark Ross failed to realise that what he referred to as "the various patches of land recently discovered by the American, French and English navigators on the verge of the Antarctic Circle" were connected to form a single continent.[157][158][159][note 5] The American explorer Mercator Cooper landed on East Antarctica on 26 January 1853.[162]

The first confirmed landing on the continental mass of Antarctica occurred in 1895 when the Norwegian-Swedish whaling ship Antarctic reached Cape Adare.[163]

20th century

During the Nimrod Expedition led by the British explorer

The American explorer Richard E. Byrd led four expeditions to Antarctica during the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s, using the first mechanised tractors. His expeditions conducted extensive geographical and scientific research, and he is credited with surveying a larger region of the continent than any other explorer.[167] In 1937, Ingrid Christensen became the first woman to step onto the Antarctic mainland.[168] Caroline Mikkelsen had landed on an island of Antarctica, earlier in 1935.[169]

The South Pole was next reached on 31 October 1956, when a U.S. Navy group led by Rear Admiral George J. Dufek successfully landed an aircraft there.[170] Six women were flown to the South Pole as a publicity stunt in 1969.[171][note 6] In the summer of 1996–1997, Norwegian explorer Børge Ousland became the first person to cross Antarctica alone from coast to coast, helped by a kite on parts of the journey.[172] Ousland holds the record for the fastest unsupported journey to the South Pole, taking 34 days.[173]

Population

The first semi-permanent inhabitants of regions near Antarctica (areas situated south of the Antarctic Convergence) were British and American sealers who used to spend a year or more on South Georgia, from 1786 onward. During the whaling era, which lasted until 1966, the population of the island varied from over 1,000 in the summer (over 2,000 in some years) to some 200 in the winter. Most of the whalers were Norwegian, with an increasing proportion from Britain.[174][note 7]

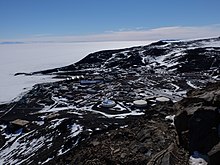

Antarctica's population consists mostly of the staff of research stations in Antarctica (which are continuously maintained despite the population decline in the winter), although there are 2 all-civilian bases in Antarctica: the Esperanza Base and the Villa Las Estrellas base.[175] The number of people conducting and supporting scientific research and other work on the continent and its nearby islands varies from about 1,200 in winter to about 4,800 in the summer, with an additional 136 people in the winter to 266 people in the summer from the 2 civilian bases (as of 2017). Some of the research stations are staffed year-round, the winter-over personnel typically arriving from their home countries for a one-year assignment. The Russian Orthodox Holy Trinity Church at the Bellingshausen Station on King George Island opened in 2004; it is manned year-round by one or two priests, who are similarly rotated every year.[176][177]

The first child born in the southern polar region was a Norwegian girl,

The

Politics

Antarctica's status is regulated by the 1959

Territorial claims

In 1539, the

In the present, sovereignty over regions of Antarctica is claimed by seven countries.[1] While a few of these countries have mutually recognised each other's claims,[190] the validity of the claims is not recognised universally.[1] New claims on Antarctica have been suspended since 1959, although in 2015, Norway formally defined Queen Maud Land as including the unclaimed area between it and the South Pole.[191]

The Argentine, British, and Chilean claims overlap and have caused friction. In 2012, after the British

Brazil has a designated "zone of interest" that is not an actual claim.[195]

Brazil has a designated "zone of interest" that is not an actual claim.[195] Peru formally reserved its right to make a claim.[194]

Peru formally reserved its right to make a claim.[194] Russia inherited the Soviet Union's right to claim territory under the original Antarctic Treaty.[196]

Russia inherited the Soviet Union's right to claim territory under the original Antarctic Treaty.[196] South Africa formally reserved its right to make a claim.[194]

South Africa formally reserved its right to make a claim.[194] The United States reserved its right to make a claim in the original Antarctic Treaty.[196]

The United States reserved its right to make a claim in the original Antarctic Treaty.[196]

| Date | Claimant | Territory | Claim limits | Map |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1840 | Originally undefined; later specified to be 142°2′E to 136°11′E |

| ||

| 1908 | 80°0′W to 20°0′W

|

| ||

| 1923 | 160°0′E to 150°0′W |

| ||

| 1931 | 68°50′S 90°35′W / 68.833°S 90.583°W |

| ||

| 1933 | 44°38′E to 136°11′E, and 142°2′E to 160°00′E |

| ||

| 1939 | 20°00′W to 44°38′E |

| ||

| 1940 | 90°0′W to 53°0′W

|

| ||

| 1943 | 74°0′W to 25°0′W

|

| ||

| – | (Unclaimed territory) | 150°0′W to 90°0′W (except Peter I Island) |

|

Human activity

Economic activity and tourism

Deposits of coal, hydrocarbons, iron ore, platinum, copper, chromium, nickel, gold, and other minerals have been found in Antarctica, but not in large enough quantities to extract.[197] The Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty, which came into effect in 1998 and is due to be reviewed in 2048, restricts the exploitation of Antarctic resources, including minerals.[198]

Tourists have been visiting Antarctica since 1957.[199] Tourism is subject to the provisions of the Antarctic Treaty and Environmental Protocol;[200] the self-regulatory body for the industry is the International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators.[201] Tourists arrive by small or medium ship at specific scenic locations with accessible concentrations of iconic wildlife.[199] Over 74,000 tourists visited the region during the 2019–2020 season, of which 18,500 travelled on cruise ships but did not leave them to explore on land.[202] The numbers of tourists fell rapidly after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Some nature conservation groups have expressed concern over the potential adverse effects caused by the influx of visitors and have called for limits on the size of visiting cruise ships and a tourism quota.[203] The primary response by Antarctic Treaty parties has been to develop guidelines that set landing limits and closed or restricted zones on the more frequently visited sites.[204]

Overland sightseeing flights operated out of Australia and New Zealand until the Mount Erebus disaster in 1979, when an Air New Zealand plane crashed into Mount Erebus, killing all of the 257 people on board. Qantas resumed commercial overflights to Antarctica from Australia in the mid-1990s.[205] There are many airports in Antarctica.

Research

In 2017, there were more than 4,400 scientists undertaking research in Antarctica, a number that fell to just over 1,100 in the winter.

The high elevation of the interior, the low temperatures, and the length of polar nights during the winter months all allow for better

Antarctica provides a unique environment for the study of meteorites: the dry polar desert preserves them well, and meteorites older than a million years have been found. They are relatively easy to find, as the dark stone meteorites stand out in a landscape of ice and snow, and the flow of ice accumulates them in certain areas. The Adelie Land meteorite, discovered in 1912, was the first to be found. Meteorites contain clues about the composition of the Solar System and its early development.[214] Most meteorites come from asteroids, but a few meteorites found in Antarctica came from the Moon and Mars.[215][note 8]

Major scientific organizations in Antarctica have released strategy and action plans focused on advancing national interests and objectives in Antarctica, supporting cutting-edge research to understand the interactions between the Antarctic region and climate systems. The

See also

Notes

- ^ The word was originally pronounced with the first c silent in English, but the spelling pronunciation has become common and is often considered more correct. However, the pronunciation with a silent c, and even with the first t silent as well, is widespread and typical of many similar English words.[2] The c had ceased to be pronounced in Medieval Latin and was dropped from the spelling in Old French, but it was added back for etymological reasons in English in the 17th century and thereafter began to be pronounced, but (as with other spelling pronunciations) at first only by less educated people.[3] For those who pronounce the first t, there is also variation between the pronunciations Ant-ar(c)tica and An-tar(c)tica.

- ^ Before the Southern Ocean was recognised as a separate ocean, it was considered to be surrounded by the southern Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian Oceans.[13]

- ^ Geographical features, such as ice caps, are shown as they are today for identification purposes, not as how they appeared at these times.

- ^ The feature discovered by the Russians was the Fimbul ice shelf.

- ^ Ross passed through what is now known as the Ross Sea and discovered Ross Island (both of which were named after him) in 1841. He sailed along a huge wall of ice that was later named the Ross Ice Shelf.[160] Mount Erebus and Mount Terror are named after two ships from his expedition: HMS Erebus and Terror.[161]

- ^ The first settlements included Grytviken, Leith Harbour, King Edward Point, Stromness, Husvik, Prince Olav Harbour, Ocean Harbour and Godthul. Managers and other senior officers of the whaling stations often lived together with their families. Among them was the founder of Grytviken, Captain Carl Anton Larsen, a prominent Norwegian whaler and explorer who, along with his family, adopted British citizenship in 1910.[174]

- ALH84001 discovered by ANSMET, were at the centre of the controversy about possible evidence of life on Mars. Because meteorites in space absorb and record cosmic radiation, the time elapsed since the meteorite hit the Earth can be calculated.[216]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Antarctica". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. 3 May 2022. Archived from the original on 9 May 2022. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- American Heritage Dictionary.

- ^ Crystal 2006, p. 172

- ^ Smith, Cynthia (21 September 2021). "Reaching the South Pole During the Heroic Age of Exploration | Worlds Revealed". The Library of Congress. Retrieved 17 April 2024.

- ^ a b "Antarctic". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. December 2021. Retrieved 17 January 2022. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Lettinck 2021, p. 158.

- ^ Hyginus 1992, p. 176.

- ^ Scott, Hiatt & McIlroy 2012, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Cawley 2015, p. 130.

- ^ McCrone & McPherson 2009, p. 75.

- ^ Cameron-Ash 2018, p. 20.

- ^ "Highlights from the Bartholomew Archive: The naming of Antarctica". The Bartholomew Archive. National Library of Scotland. Archived from the original on 18 February 2022. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- ^ "How many oceans are there?". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 20 August 2023. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- ^ Drewry 1983.

- ^ a b Trewby 2002, p. 115.

- ^ Day 2019, Is all of Antarctica snow-covered?.

- ^ Carroll & Lopes 2019, p. 99.

- .

- (PDF) from the original on 16 February 2020. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- ^ Lucibella, Michael (21 October 2015). "The Lost Dry Valleys of the Polar Plateau". The Antarctic Sun. United States Antarctic Program. Archived from the original on 15 January 2022. Retrieved 16 January 2022.

- ^ Hallberg, Robert; Sergienko, Olga (2019). "Ice Sheet Dynamics". Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory. Archived from the original on 28 April 2021. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ^ Siegert & Florindo 2008, p. 532.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 6 March 2022. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- ISSN 0012-821X.

- ^ Monteath 1997, p. 135.

- ^ Trewby 2002, p. 75.

- ^ Carroll & Lopes 2019, p. 38.

- ^ Hund 2014, pp. 362–363.

- ^ Browne, Malcolm W.; et al. (1995). Antarctic News Clips. National Science Foundation. p. 109. Archived from the original on 14 August 2023. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ Trewby 2002, p. 92.

- from the original on 22 April 2021. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- ^ Cantrill & Poole 2012, p. 31.

- from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 14 February 2021.

- ^

- ISBN 978-0-12-817925-3.

- ^ a b Collinson, James; William R., Hammer (2007). "Migration of Triassic tetrapods to Antarctica". United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 2 April 2022. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

- ^ Jasinoski 2013, p. 139.

- from the original on 29 April 2021. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- ^ Cantrill & Poole 2012, pp. 9, 35, 56, 71, 185, 314.

- S2CID 131433262.

- ^ Riffenburgh 2007, p. 413.

- ^ Smith, Nathan D.; Pol, Diego (2007). "Anatomy of a basal sauropodomorph dinosaur from the Early Jurassic Hanson Formation of Antarctica" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 52 (4): 657–674. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- hdl:11336/76749.

- .

- S2CID 146325060.

- ^ Leslie, Mitch (December 2007). "The Strange Lives of Polar Dinosaurs". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on 30 January 2008. Retrieved 24 January 2008.

- .

- ^ Defler 2019, pp. 185–198

- doi:10.13679/j.advps.2019.0021. Archived from the originalon 6 January 2022. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- from the original on 18 October 2021. Retrieved 18 October 2021.

- S2CID 11271131.

- S2CID 133542067.

- (PDF) from the original on 9 August 2023. Retrieved 4 January 2023.

- PMID 27917060.

- ^ Trewby 2002, p. 88.

- from the original on 2 April 2022. Retrieved 17 March 2022 – via ScienceDirect.

- ^ Stonehouse 2002, p. 116.

- from the original on 14 August 2023. Retrieved 18 March 2023.

- ^ Trewby 2002, pp. 144, 197–198.

- ^ Anderson 2010, p. 28.

- ^ Trewby 2002, p. 71.

- ^ Campbell & Claridge 1987.

- S2CID 56243069. Archived from the originalon 27 November 2020. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- .

- ^ Trewby 2002, p. 124.

- New York Times. Archivedfrom the original on 14 March 2022. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- United States Geographical Survey. Santa Barbara, California: United States Department of the Interior. p. 12. Archived(PDF) from the original on 7 January 2016. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ISSN 2156-2202.

- ^ Rice, Doyle (10 December 2013). "Antarctica records unofficial coldest temperature ever". USA Today. Gannett. Archived from the original on 7 February 2021. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- Government of Australia. 18 February 2019. Archivedfrom the original on 13 January 2022. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- ^ "Antarctic weather". Australian Antarctic Program. 18 February 2019. Archived from the original on 13 January 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- S2CID 22195720.

- S2CID 13190037. Archived from the originalon 7 May 2021. Retrieved 12 October 2020 – via Wiley Online Library.

- ^ Rohli & Vega 2018, p. 241.

- ^ "Facts / Vital signs / Ice Sheets / Antarctica Mass Variation Since 2002". climate.NASA.gov. NASA. 2020. Archived from the original on 9 December 2020.

- S2CID 222179485.

- ^ Steig, Eric; Schneider, David; Rutherford, Scott; Mann, Michael E.; Comiso, Josefino; Shindell, Drew (1 January 2009). "Warming of the Antarctic ice-sheet surface since the 1957 International Geophysical Year". Arts & Sciences Faculty Publications.

- ^ a b "Impacts of climate change". Discovering Antarctica. Retrieved 15 May 2022.

- S2CID 220261150.

- .

- PMID 35039511.

- ^ a b c d Fox-Kemper, B.; Hewitt, H.T.; Xiao, C.; Aðalgeirsdóttir, G.; Drijfhout, S.S.; Edwards, T.L.; Golledge, N.R.; Hemer, M.; Kopp, R.E.; Krinner, G.; Mix, A. (2021). Masson-Delmotte, V.; Zhai, P.; Pirani, A.; Connors, S.L.; Péan, C.; Berger, S.; Caud, N.; Chen, Y.; Goldfarb, L. (eds.). "Chapter 9: Ocean, Cryosphere and Sea Level Change" (PDF). Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA: 1270–1272.

- .

- PMID 31110015.

- S2CID 218541055.

- PMID 29675467.

- PMID 35013425.

- ^ Lenton, T. M.; Armstrong McKay, D.I.; Loriani, S.; Abrams, J.F.; Lade, S.J.; Donges, J.F.; Milkoreit, M.; Powell, T.; Smith, S.R.; Zimm, C.; Buxton, J.E.; Daube, Bruce C.; Krummel, Paul B.; Loh, Zoë; Luijkx, Ingrid T. (2023). The Global Tipping Points Report 2023 (Report). University of Exeter.

- ^ Logan, Tyne (29 March 2023). "Landmark study projects 'dramatic' changes to Southern Ocean by 2050". ABC News.

- S2CID 53093132.

- ^ Carlson, Anders E; Walczak, Maureen H; Beard, Brian L; Laffin, Matthew K; Stoner, Joseph S; Hatfield, Robert G (10 December 2018). Absence of the West Antarctic ice sheet during the last interglaciation. American Geophysical Union Fall Meeting.

- S2CID 266436146.

- S2CID 264476246.

- S2CID 221885420.

- ^ S2CID 252161375.

- ^ a b c Armstrong McKay, David (9 September 2022). "Exceeding 1.5°C global warming could trigger multiple climate tipping points – paper explainer". climatetippingpoints.info. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- ^ PMID 33931453.

- (PDF) from the original on 16 February 2020. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- PMID 36088458.

- hdl:1721.1/99159. Archivedfrom the original on 27 February 2021. Retrieved 7 February 2021 – via MIT Open Access Articles.

- ^ PMID 19675624.

- ^ Bates, Sofie (30 October 2020). "Large, Deep Antarctic Ozone Hole Persisting into November". NASA. Archived from the original on 31 October 2020. Retrieved 6 February 2021.

- ^ "Record-breaking 2020 ozone hole closes". World Meteorological Organization. 6 January 2021. Retrieved 6 February 2021.

- ^ "The Ozone Hole". British Antarctic Survey. 1 April 2017. Archived from the original on 4 March 2022. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ^ "Q10: Why has an "ozone hole" appeared over Antarctica when ozone-depleting substances are present throughout the stratosphere?" (PDF). 20 Questions: 2010 Update. NOAA. 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 April 2021. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ "World Meteorological Organization Global Ozone Research and Monitoring Project—Report No. 58: Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion 2018" (PDF). Scientific Assessment Panel (SAP). World Meteorological Organization. ES.3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 December 2019. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- PMID 31262810.

- from the original on 5 October 2022. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- ISBN 978-0-12-817925-3.

- ^ "Land Animals of Antarctica". British Antarctic Survey. Natural Environment Research Council. Archived from the original on 7 October 2008. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- ^ Sandro, Luke; Constible, Juanita. "Antarctic Bestiary – Terrestrial Animals". Laboratory for Ecophysiological Cryobiology. Miami University. Archived from the original on 4 May 2019. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- ^ Trewby 2002, p. 114.

- ^ Elsevier Science Direct.

- ^ Stromberg 1991, p. 247

- PMID 29870541.

- ISBN 978-3-540-93922-1.

- ^ Kinver, Mark (15 February 2009). "Ice oceans 'are not poles apart'". BBC News. Archived from the original on 16 April 2016. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- ^ "Plants of Antarctica". British Antarctic Survey. Natural Environment Research Council. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- ^ Bridge, Paul D.; Spooner, Brian M.; Roberts, Peter J. (2008). "Non-lichenized fungi from the Antarctic region". Mycotaxon. 106: 485–490. Archived from the original on 11 August 2013. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- ^ a b c Selbmann, L; de Hoog, G S; Mazzaglia, A; Friedmann, E. I.; Onofri, S (2005). "Fungi at the edge of life: cryptoendolithic black fungi from Antarctic desert" (PDF). Studies in Mycology. 51: 1–32. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 April 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- S2CID 73420634.

- ^ de Hoog 2005, p. vii.

- PMID 23702515.

- S2CID 46651929.

- from the original on 18 March 2021. Retrieved 27 January 2019.

- Government of Australia. Archivedfrom the original on 19 August 2020. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- S2CID 3759495.

- ^ kazilek (15 July 2014). "Brine Channels". askabiologist.asu.edu. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ Gorman, James (6 February 2013). "Bacteria Found Deep Under Antarctic Ice, Scientists Say". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 January 2022. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- S2CID 8399775.

- from the original on 2 April 2022. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- PMID 31134036.

- ^ Hoover, Richard Brice; Pikuta, Elena V. (January 2010). "5.4: Microbial Extremophiles from Lake Untersee". Psychrophilic and Psychrotolerant Microbial Extremophiles in Polar Environments (PDF) (Report). NASA. pp. 25–26. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 January 2022. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

- ^ Coulter, Dana. Tony Phillips (ed.). "Extremophile Hunt Begins". Science News. NASA. Archived from the original on 23 March 2010. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- ^ PMID 30808907.

- ^ "Toothfish fisheries". Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources. 2 July 2021. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- ^ Day 2019, The Antarctic Treaty of 1959.

- ^ "The Madrid Protocol". Australian Antarctic Division. 17 May 2019. Archived from the original on 15 August 2020. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- ^ "Protocol on Environmental Protection To The Antarctic Treaty (The Madrid Protocol)". Australian Antarctic Programme. 17 May 2019. Archived from the original on 15 August 2020. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ "Now you see it now you don't!" (PDF). ECO. Vol. 82, no. 3. November 1992. p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 February 2022. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- ^ "Southern Ocean Whale Sanctuary". Antarctic and Southern Coalition. Archived from the original on 13 January 2022. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- S2CID 89943276.

- ISBN 9780820343594.

- ^ Riffenburgh 2007, p. 296.

- ^ Edwards 1999, p. 250.

- ^ Beaglehole 1968, p. 643.

- ^ Henriques, Martha (22 October 2018). "The bones that could shape Antarctica's fate". BBC Future. Archived from the original on 22 July 2021. Retrieved 22 July 2021.

- ^ Trewby 2002, p. 39.

- ^ Trewby 2002, p. 139.

- ^ Tammiksaar, Erki (14 December 2013). "Punane Bellingshausen" [Red Bellingshausen]. Postimees (in Estonian). Archived from the original on 13 February 2022. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

- S2CID 129664580.

- ^ Baughmann 1994, p. 133

- ^ Joyner 1992, p. 5.

- ^ Trewby 2002, p. 67.

- from the original on 2 April 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ Cawley 2015, p. 131.

- ^ Ainsworth 1847, p. 479.

- from the original on 6 December 2022. Retrieved 6 December 2022 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Trewby 2002, p. 154.

- ^ Trewby 2002, pp. 154, 185.

- ^ Day 2013, p. 88.

- ^ Pyne 2017, p. 85

- ^ "Tannatt William Edgeworth David". Australian Antarctic Division. Archived from the original on 29 September 2010. Retrieved 27 September 2010.

- ^ Riffenburgh 2007, pp. 30–32.

- ^ Trewby 2002, p. 159.

- ^ Trewby 2002, p. 44.

- ^ Blackadder, Jesse (December 2012). "The first woman in Antarctica". Australian Antarctic Program. Australian Antarctic Division. Archived from the original on 13 April 2020. Retrieved 27 June 2016.

- from the original on 20 February 2022. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ "Dates in American Naval History: October". Naval History and Heritage Command. United States Navy. Archived from the original on 26 June 2004. Retrieved 12 February 2006.

- ^ a b "Pamela Young". Royal Society Te Apārangi. Archived from the original on 21 February 2022. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- from the original on 10 October 2019. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- ^ "Fastest unsupported (kite assisted) journey to the South Pole taking just 34 days". Guinness World Records. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- ^ a b Headland 1984, p. 238.

- ^ "Antarctica". Resource Library. National Geographic. 4 January 2012. Archived from the original on 2 March 2021. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- ^ "Flock of Antarctica's Orthodox temple celebrates Holy Trinity Day". Serbian Orthodox Church. 24 May 2004. Archived from the original on 26 August 2016. Retrieved 7 February 2009.

- ^ Владимир Петраков: 'Антарктика – это особая атмосфера, где живут очень интересные люди' [Vladimir Petrakov: "Antarctic is a special world, full of very interesting people"]. Pravoslavye (in Russian). 28 April 2021. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 28 February 2009.

- ^ Headland 1984, pp. 12, 130.

- ^ Russell 1986, p. 17

- ^ "Antarctic Treaty". Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research. Archived from the original on 6 February 2006. Retrieved 9 February 2006.

- Antarctica Institute of Argentina. Archived from the originalon 6 March 2006. Retrieved 9 February 2006.

- ^ "Parties". Secretariat of the Antarctic Treaty. Archived from the original on 23 February 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- S2CID 239218549.

- ^ M. Wright, Note, "The Ownership of Antarctica, its Living and Mineral Resources", Journal of Law and the Environment Vol. 4, 1987.

- ^ Pinochet de la Barra, Óscar (November 1944). La Antártica Chilena. Editorial Andrés Bello.

- ^ Calamari, Andrea (June 2022). "El conjurado que gobernó la Antártida" (in Spanish). Jot Down. Archived from the original on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- ^ "Pedro Sancho de la Hoz" (in Spanish). Real Academia de la Historia. Archived from the original on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 25 August 2022.

- ^ "1544" (in Spanish). Biografía de Chile. Archived from the original on 19 August 2022. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- Santiago de Chile: Instituto de Estudios Internacionales, Universidad de Chile; Editorial Universitaria. Archivedfrom the original on 19 August 2022. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- ^ a b Von Tigerstrom & Leane 2005, p. 204.

- ^ Rapp, Ole Magnus (21 September 2015). "Norge utvider Dronning Maud Land helt frem til Sydpolen". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). Oslo. Archived from the original on 21 February 2022. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ "The Foreign Secretary has announced that the southern part of British Antarctic Territory has been named Queen Elizabeth Land". Foreign & Commonwealth Office. HM Government. 18 December 2012. Archived from the original on 7 July 2013. Retrieved 22 December 2012.

- ^ "Argentina angry after Antarctic territory named after Queen". BBC News. 22 December 2012. Archived from the original on 15 January 2013. Retrieved 22 December 2012.

- ^ a b c Ribadeneira, Diego (1988). "La Antartida" (PDF). AFESE (in Spanish). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ Morris 1988, p. 219

- ^ a b "Disputes – international". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. 2011. Archived from the original on 15 September 2020. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

... the US and Russia reserve the right to make claims ...

- ^ "Natural Resources". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 3 April 2022. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ^ Press, Tony (5 October 2016). "Antarctica: The Madrid Protocol 25 Years On". Australian Institute of International Affairs. Archived from the original on 18 January 2022. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- ^ a b Trewby 2002, pp. 187–188.

- ^ "During Your Visit". International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators. Archived from the original on 7 June 2020. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ^ Trewby 2002, p. 107.

- ^ "IAATO Antarctic visitor figures 2019–2020". Data & Statistics. International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators. July 2020. Archived from the original on 9 June 2020. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ^ Rowe, Mark (11 February 2006). "Tourism threatens the Antarctic". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 24 February 2008. Retrieved 5 February 2006.

- ^ "Tourism and Non-Governmental Activities". Secretariat of the Antarctic Treaty. Archived from the original on 30 September 2019. Retrieved 7 February 2022.

- ^ Day 2013, pp. 507–509.

- ^ Hund 2014, p. 41.

- S2CID 132258248.

- ^ Carroll & Lopes 2019, p. 160.

- from the original on 8 February 2021. Retrieved 8 February 2021 – via Elsevier Science Direct.

- ^ "Human Biology and Medicine". Australian Antarctic Programme. 16 September 2020. Archived from the original on 22 August 2020. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- S2CID 16843819.

- ^ "Science Goals: Celebrating a Century of Science and Exploration". National Science Foundation. 2011. Archived from the original on 29 December 2007. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- ^ "IceCube Quick Facts". IceCube Neutrino Observatory. Archived from the original on 13 February 2021. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- ^ "Finding Meteorite Hotspots in Antarctica". Earth Observatory. NASA. 9 March 2022. Archived from the original on 9 March 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ Talbert, Tricia (14 November 2016). "Science from the Sky: NASA Renews Search for Antarctic Meteorites". NASA. Archived from the original on 19 November 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ "Meteorites from Antarctica". NASA. Archived from the original on 6 March 2006. Retrieved 9 February 2006.

- ^ "British Antarctic Survey" (PDF). bas.ac.uk. British Antarctic Survey. Retrieved 27 March 2024.

- ^ "British Antarctic Survey" (PDF). bas.ac.uk. British Antarctic Survey. Retrieved 27 March 2024.

- ^ "Australian Antarctic Science Strategic Plan" (PDF). Australian Antarctic Science Council. Retrieved 27 March 2024.

- ISBN 978-0-309-26818-9. Retrieved 27 March 2024.

- ISBN 978-0-309-26818-9. Retrieved 27 March 2024.

- ^ a b "ICE SHEETS AND SEA-LEVEL RISE". antarctica.gov.au. Australian Antarctic Program. 2 February 2014. Retrieved 27 March 2024.

Bibliography

- Ainsworth, William Harrison, ed. (1847). "The Antarctic Voyage of Discovery". The New Monthly Magazine and Humourist. London: Chapman & Hall.

- Anderson, John B. (2010). Antarctic Marine Geology. Cambridge: ISBN 978-05211-3-168-1.

- ISBN 978-0-8032-1228-2.

- ISBN 978-1-4724-5324-2.

- Cameron-Ash, Margaret (2018). Lying for the Admiralty. Sydney: Rosenberg Publishing. ISBN 978-06480-4-396-6.

- Campbell, I.B.; Claridge, G.G.C., eds. (1987). "Chapter 2 the Geology and Geomorphology of Antarctica". Antarctica: Soils, Weathering Processes and Environment. Developments in Soil Science. Vol. 16. Amsterdam: ISSN 0166-2481.

- Cantrill, David J.; Poole, Imogen (2012). The Vegetation of Antarctica through Geological Time. Cambridge: ISBN 978-1-139-56028-3.

- Carroll, Michael; Lopes, Rosaly (2019). Antarctica : Earth's Own Ice World. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Praxis Books. ISBN 978-3-319-74623-4.

- Cawley, Charles (2015). Colonies in Conflict: The History of the British Overseas Territories. Newcastle: ISBN 978-14438-8-128-9.

- ISBN 978-0-19-920764-0.

- ISBN 978-0-19-967055-0.

- Day, David (2019). Antarctica: What Everyone Needs to know. Oxford: ISBN 978-0-19-064132-0.

- ISBN 978-3-319-98448-3.

- ISBN 978-0-901021-04-5.

- ISBN 978-0-14-192808-1.

- Headland, Robert (1984). The Island of South Georgia. Cambridge: ISBN 978-0-521-25274-4.

- de Hoog, G.S. (2005). "Fungi of the Antarctic: evolution under extreme conditions" (PDF). ISBN 9789070351557.

- Hund, Andrew J., ed. (2014). Antarctica And The Arctic Circle: A Geographic Encyclopedia of the Earth's Polar Regions. Vol. 1. ABC-CLIO, LLC. ISBN 978-1-61069-392-9.

- ISBN 978-35190-1-438-6.

- Jasinoski, Sandra C.; et al. (2013). "Anatomical Plasticity in the Snout of Lystrosaurus". In Kammerer, Christian F.; Frobisch, Jörg; Angielczyk, Kenneth D. (eds.). Early Evolutionary History of the Synapsida. ISBN 978-94-007-6841-3.

- ISBN 978-0-7923-1823-1.

- Lettinck, Paul (2021). Aristotle's Meteorology and Its Reception in the Arab World. Leiden; Boston (Massachusetts): ISBN 978-90-04-44917-6.

- McCrone, David; McPherson, Gayle, eds. (2009). National Days: Constructing and Mobilising National Identity. Basingstoke, UK: ISBN 978-02302-5-117-5.

- Monteath, Colin (1997). Hall & Ball Kiwi Mountaineers: from Mount Cook to Everest. Christchurch: Cloudcap. ISBN 978-0-938567-42-4.

- Morris, Michael (1988). The Strait of Magellan. Dordrecht; London: ISBN 978-0-7923-0181-3.

- ISBN 978-0-295-80523-8.

- ISBN 978-1-1358-7866-5.

- Rohli, Robert V.; Vega, Anthony J. (2018). Climatology (4th ed.). Burlington, Massachusetts: ISBN 978-1-284-12656-3.

- Russell, Alan (1986). ISBN 978-0-8069-4768-6.

- Scott, Anne W.; Hiatt, Alfred; McIlroy, Claire, eds. (2012). European Perceptions of Terra Australis. Farnham, UK: ISBN 978-1-4094-3941-7.

- ISBN 978-0-08-093161-6.

- Stromberg, O.; et al. (1991). Nemoto, Takahisa; Mauchline, John (eds.). Marine Biology: Its Accomplishment and Future Prospect. ISBN 978-0-444-98696-2.

- ISBN 978-0-471-98665-2.

- Thomas, David Neville (2007). Surviving Antarctica. London: ISBN 978-0-565-09217-7.

- Von Tigerstrom, Barbara; Leane, Geoffrey W. G., eds. (2005). International Law Issues in the South Pacific. Aldershot, UK; Burlington, Vermont: ISBN 978-0-7546-4419-4.

- Trewby, Mary, ed. (2002). Antarctica: An Encyclopedia from Abbott Ice Shelf to Zooplankton. Buffalo, New York: Firefly Books. ISBN 978-1-55297-590-9.

- "British Antarctic Survey" (PDF). bas.ac.uk. British Antarctic Survey. Retrieved 27 March 2024.

- "Australian Antarctic Science Strategic Plan" (PDF). Australian Antarctic Science Council. Retrieved 27 March 2024.

- Mid-Term Assessment of Progress on the 2015 Strategic Vision for Antarctic and Southern Ocean Research. The National Academies Press. 2021. ISBN 978-0-309-26818-9. Retrieved 27 March 2024.

- "ICE SHEETS AND SEA-LEVEL RISE". antarctica.gov.au. Australian Antarctic Program. 2 February 2014. Retrieved 27 March 2024.

Further reading

- De Pomereu, Jean; and McCahey, Daniella. Antarctica: A History in 100 Objects (Conway, 2022) online book review

- Kleinschmidt, Georg (2021). The geology of the Antarctic continent. Stuttgart: Bornträger Science Publisher. ISBN 978-3-443-11034-5.

- Lucas, Mike (1996). Antarctica. ISBN 978-1-85368-743-3.

- ISBN 978-18974-7-235-4 – via Internet Archive.

- Stewart, John (2011). Antarctica: An Encyclopedia. Jefferson, N.C. and London: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-3590-6.

- Ivanov, Lyubomir; Ivanova, Nusha (2022). The World of Antarctica. Generis Publishing. 241 pp. ISBN 979-8-88676-403-1

External links

- High resolution map (2022) – Reference Elevation Model of Antarctica (REMA)

- Antarctica. on In Our Time at the BBC

- Official website of the Antarctic Treaty Secretariat (de facto government)

- British Antarctic Survey (BAS)

- U.S. Antarctic Program Portal