Antarctica during World War II

International competition extended to the continent of Antarctica during the World War II era, though the region saw no combat. During the prelude to war, Nazi Germany organised the 1938 Third German Antarctic Expedition to preempt Norway's claim to Queen Maud Land.[1] The expedition served as the basis for a new German claim, called New Swabia.[2] A year later, the United States Antarctic Service Expedition established two bases, which operated for two years before being abandoned.[3] Responding to these encroachments, and taking advantage of Europe's wartime turmoil, the nearby nations of Chile and Argentina made their own claims. In 1940 Chile proclaimed the Chilean Antarctic Territory in areas already claimed by Britain, while Argentina proclaimed Argentine Antarctica in 1943 in an overlapping area.

In response to the activities of Germany, Chile, Argentina, and the United States, Britain launched Operation Tabarin in 1943. Its objective was to establish a permanent presence and assert Britain's claim to the Falkland Islands Dependencies,[4] as well as to deny use of the area to the Kriegsmarine, which was known to use remote islands as rendezvous points. There was also a fear that Japan might attempt to seize the Falkland Islands. The expedition under Lieutenant James Marr[5] left the Falklands on 29 January 1944. Bases were established on Deception Island, the coast of Graham Land, and at Hope Bay. The research begun by Operation Tabarin continued in subsequent years, ultimately becoming the British Antarctic Survey.[6]

In the postwar period, competition continued among Antarctica's claimant powers, as well as the United States and Soviet Union. In the late 1950s, this competition would gave way to a cooperative international framework with the International Geophysical Year and the Antarctic Treaty.

Third German Antarctic Expedition and New Swabia (1938–1939)

United States Antarctic Service Expedition (1939–1941)

The United States Antarctic Service Expedition was the first government funded Antarctic expedition since the

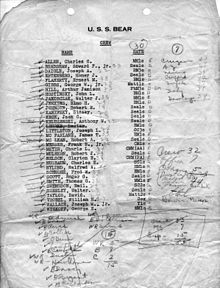

The Team brought along a newly designed Antarctic Snow Cruiser which had smooth tract-less tires which made it difficult to grip onto the Antarctic ice.[19] Due to this problem and constant repair and maintenance on the tires the vehicle was abandoned when the expedition team evacuated.[20] It was found years later during Operation Highjump and once more in 1958. It is now suspected to be lost to the sea or buried under mounds of ice and snow.[21] The crew of the mission which included Richard Black and Paul Siple[22] conducted multiple experiments and observations including collecting samples of plants, algae and lichen.[23] The mission resulted in a better understanding of polar science.[24] With World War II ramping up the U.S government deemed it wise to evacuate the two bases. West Base cleared on 1 February 1941 and East Base followed suite on 22 March 1941. The ships USMS North star and Bear of Oakland arrived on 5 May 1941 and 18 May 1941 respectively.[25]

German Pacific Commerce Raiders (1940–1943)

During World War II, Nazi Germany constructed a commerce-raiding fleet of Auxiliary Merchant Cruisers destined to sail through the Pacific and disrupt Allied shipping.[26] The main goal of these raiders was to destroy and capture enemy shipping. The Germans constructed 9 ships which were merchant ships that were converted to armed raiders with 5.9 inch guns and torpedo tubes.[27] They were often disguised as neutral vessels.[28]

While the ships mainly spent time in warmer waters near Asia many did stray into colder waters. The Atlantis for example stopped at Kerguelen Islands in December 1940 to rest and resupply on water and food.[29][30] The ship suffered its first wartime casualty when they lost Bernhard Herrmann after an accident on Christmas eve.[31] Many of the raiders used the islands as a stopping ground to swap disguises and refuel.[32] The cruiser Pinguin captured a fleet of Norwegian fishers on 14 January 1941 near South Georgia.[33][34]

German presence in the Pacific dwindled until the last ship was sunk or captured in the mid 1940s.

Argentine expeditions (1942 and 1943)

Argentina conducted two expeditions during the Second World War.[35] The first occurred in late 1942, the second in February 1943.[35]

1942 expedition

The first expedition happened in 1942 when the ship Primero De Mayo captained by Alberto J. Oddera landed on Deception Island where surveying was conducted. Following the surveying the crew of the expedition planted a flag to claim the area for Argentina.[36]

1943 expedition

The 1943 expedition occurred in February following the destruction of the previous expeditions flag by MV Carnarvon Castle.[37] The expedition was largely uneventful with little activity besides photographic surveys of the Port Lockroy area.[35]

Operation Tabarin (1943–1946)

Operation Tabarin was a secret mission undertaken by the British

The rest of the expedition team left for

In February 1945 Fitzroy, William Scorresby and the

Secret Nazi Bunker

Throughout the years, rumors of a hidden German base in the Antarctic have persisted, stemming from theories of escaped Nazi leaders and the appearance of a U-boat in July 1945.[58] The theory was set forward by the Hungarian Ladislas Szabo, who set forth the idea in 1947.[59] Many noted scientists such as Colin Summerhayes have disproved these theories in peer reviewed papers.[60][61][62] They prove through declassified documents that the Nazi regime was present in Antarctica for only a month in 1939 on a simple surveying expedition which left little time to build a city-sized structure in the ice.[63]

References

- ^ Widerøe, Turi (2008). "Annekteringen av Dronning Maud Land". Norsk Polarhistorie (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 15 July 2011.

- ^ D. T. Murphy, German exploration of the polar world. A history, 1870–1940 (Nebraska 2002), p. 204.

- ^ Bertrand, Kenneth J. (1971). Americans in Antarctica 1775–1948. New York: American Geographical Society.

- ^ "About – British Antarctic Survey". www.antarctica.ac.uk. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- ^ "Scott Polar Research Institute, Cambridge » Picture Library catalogue". www.spri.cam.ac.uk. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- ^ "Operation Tabarin overview". British Antarctic Survey – Polar Science for Planet Earth. British Antarctic Survey. 2015. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- ^ "Antarctica - National rivalries and claims". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2021-03-07.

- ^ MS Schwabenland / DOFW, MS Schwabenland / DOFW (2021-03-07). "MS Schwabenland / DOFW". DOFW. Archived from the original on 2005-02-25.

- S2CID 129305837.

- ^ Niiler, Eric. "Hitler Sent a Secret Expedition to Antarctica in a Hunt for Margarine Fat". HISTORY. Retrieved 2021-03-07.

- ^ Grossman, David (2017-03-14). "Nope, There Was Never a Secret Nazi Base in Antarctica". Popular Mechanics. Retrieved 2021-03-07.

- ^ "Antarctic Explorers: Richard E. Byrd: The US Antarctic Service Expedition 1939-41". www.south-pole.com. Retrieved 2021-03-10.

- ^ "Richard E. Byrd". Virginia Museum of History & Culture. Retrieved 2021-05-22.

- ^ Dewing, Charles E.; Kelsay, Laura E. (1955). "RECORDS OF THE UNITED STATES ANTARCTIC SERVICE" (PDF). The National Archives of the United States: 6 and 7.

- JSTOR 4250004.

- JSTOR 4250004.

- ^ "Bear, 1885". United States Coast Guard. Retrieved 2021-03-11.

- JSTOR 4250004.

- ^ Holderith, Peter (29 October 2020). "Scientists Find Probable Location of Massive Polar Exploration Vehicle Lost for Decades". The Drive. Retrieved 2021-03-11.

- ^ Taylor, Alan. "The Antarctic Snow Cruiser—Updated - The Atlantic". www.theatlantic.com. Retrieved 2021-03-13.

- S2CID 128811407.

- JSTOR 1797429.

- ^ "Byrd Antarctic Expedition | Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History". naturalhistory.si.edu. Retrieved 2021-03-11.

- JSTOR 985310.

- ^ "Antarctic Postal History: An Introduction to B.A.E. III Philately". www.south-pole.com. Retrieved 2021-03-11.

- ^ Ghaleb, Sam. "German Merchant Cruiser Komet hits seas". Ocean City Today. Retrieved 2021-03-16.

- ^ "German Raiders in the Pacific | NZETC". nzetc.victoria.ac.nz. Retrieved 2021-03-17.

- ISBN 978-1-78200-001-3.

- ISBN 9780275966850.

- ^ "The Atlantis: The Kriegsmarine's Last Corsair". Warfare History Network. 2016-11-08. Retrieved 2021-05-21.

- ^ "Kerguelen Islands, French Southern and Antarctic Lands (Part 2) - Iles Kerguelen, TAAF". www.discoverfrance.net. Retrieved 2021-05-21.

- ^ "Antarctic Exploration Timeline - 1940s". ku-prism.org. Archived from the original on 2021-10-28. Retrieved 2021-05-21.

- ^ "Norwegian Victims of Pinguin - Norwegian Merchant Fleet 1939-1945". www.warsailors.com. Retrieved 2021-05-21.

- ^ Bennet, H. J. (1954). Cruise Of The Raider HK 33. Thomas Y. Crowell Company. pp. 192–202.

- ^ a b c Argentine Antarctic Expeditions, 1942, 1943, 1947, and 1947–48. (1953). Polar Record, 6(45), 656-662. doi:10.1017/S0032247400047835

- JSTOR 40507108– via JSTOR.

- ^ "Scott Polar Research Institute, Cambridge » Picture Library catalogue". www.spri.cam.ac.uk. Retrieved 2021-05-21.

- ^ "Scott Polar Research Institute, Cambridge » SPRI Museum news". University of Cambridge. Retrieved 2021-03-08.

- ^ "Operation Tabarin overview". British Antarctic Survey. Retrieved 2021-03-07.

- ISSN 1475-3057.

- ArcGIS Online. Retrieved 2021-03-09.

- ^ "'The late Sir Ernest Shackleton and the Crew of the "Quest"' (including Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton)". National Portrait Gallery. Retrieved 2021-03-08.

- ^ "AD6-24-1-5". British Antarctic Survey Club. Retrieved 2021-03-08.

- ^ "List of Tabarin personnel". British Antarctic Survey. Retrieved 2021-03-08.

- ^ "AD6-24-1-2". British Antarctic Survey Club. Retrieved 2021-03-08.

- ^ "History of Port Lockroy (Station A)". British Antarctic Survey. Retrieved 2021-03-08.

- ^ "Departure Notes" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-05-17.

- ^ Dickinson, Anthony (January 2016). "Maritime Support for Great Britain's Antarctic Sovereignty Claim: Operation Tabarin and the 1944-45 Voyage of the Newfoundland Sealing Ship Eagle" (PDF). The Northern Mariner. XXVI (1): 1–20.

- ^ "Transition". British Antarctic Survey. Retrieved 2021-03-09.

- ^ "History of Hope Bay (Station D)". British Antarctic Survey. Retrieved 2021-03-08.

- ^ "Dog sledging". British Antarctic Survey. Retrieved 2021-03-08.

- ^ "Celebrating the anniversary of Operation Tabarin". GOV.UK. Retrieved 2021-03-08.

- ^ "Operation Tabarin 75th Anniversary". British Antarctic Survey. Archived from the original on 2022-10-09. Retrieved 2021-03-08.

- ^ "Port Lockroy". British Antarctic Survey. Archived from the original on 2016-02-07. Retrieved 2021-03-08.

- ^ "Conservation of historic British bases in Antarctica". British Antarctic Survey. Retrieved 2021-03-08.

- ^ "Antarctica In Sight". UK Antarctica Heritage Trust. Retrieved 2021-03-08.

- ^ "A new beginning". British Antarctic Survey. Retrieved 2021-03-08.

- ^ "Fake News About a Secret Nazi UFO Base In Antarctica Refuses to Die". www.vice.com. Retrieved 2021-05-21.

- ^ Moncure, Billy (2018-10-28). "The Secret Nazi Super Fortress in Antarctica - Fact or Fiction?". WAR HISTORY ONLINE. Retrieved 2021-05-21.

- ^ "Hitler on Ice: Did the Nazis Have a Secret Antarctic Fortress?". www.mentalfloss.com. 2012-03-19. Retrieved 2021-05-21.

- ^ Summerhayes, Colin (May 2006). "Hitler's Antarctic base: the myth and the reality" (PDF). Polar Record. 43. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-12-13. Retrieved 2021-05-21 – via PDF.

- ^ "Weird Antarctica - the truth behind secret Nazi bases and aliens". ABC Radio National. 2020-06-05. Retrieved 2021-05-21.

- ^ "The Nazi Bunkers of Antarctica | The Psychology of Extraordinary Beliefs". u.osu.edu. Retrieved 2021-05-21.