Antiochus I Soter

| Antiochus I | |

|---|---|

| |

| Died | 2 June 261 BC (aged 61–63) |

| Spouse | Stratonice |

| Issue |

|

Mesopotamian religion[1] and Greek polytheism | |

Antiochus I Soter (Greek: Ἀντίοχος Σωτήρ, Antíochos Sōtér; "Antiochus the Savior"; c. 324/3 – 2 June 261 BC) was a Macedonian king of the Seleucid Empire.[2] Antiochus succeeded his father Seleucus I Nicator in 281 BC and reigned during a period of instability which he mostly overcame until his death on 2 June 261 BC.[3] He is the last known ruler to be attributed the ancient Mesopotamian title King of the Universe.[4]

Biography

Antiochus's father was Seleucus I Nicator[5][6] and his mother was Apama, daughter of Spitamenes,[7][8] being one of the princesses whom Alexander the Great had given as wives to his generals in 324 BC.[9][10] The Seleucids fictitiously claimed that Apama was the daughter of Darius III, in order to legitimise themselves as the inheritors of both the Achaemenids and Alexander, and therefore the rightful lords of western and central Asia.[11]

In 294 BC, prior to the death of his father

The Ruin of Esagila Chronicle, dated between 302 and 281 BC, mentions that a crown prince, most likely Antiochus, decided to rebuild the ruined Babylonian temple Esagila, and made a sacrifice in preparation. However, while there, he stumbled on the rubble and fell. He then ordered his troops to destroy the last of the remains.[13]

On the assassination of his father in 281 BC, the task of holding together the empire was a formidable one. A revolt in

In 278 BC the

At the end of 275 BC the question of

In 268 BC Antiochus I laid the foundation for the Ezida Temple in

Ai-Khanoum

Recent analysis strongly suggests that the city of

Relations with India

Antiochus I maintained friendly diplomatic relations with

Antiochus is probably the Greek king mentioned[24] in the Edicts of Ashoka, as one of the recipients of the Indian Emperor Ashoka's Buddhist proselytism:

And even this conquest [preaching Buddhism] has been won by the Beloved of the Gods here and in all the borderlands, as far as six hundred

Ashoka also claims that he encouraged the development of herbal medicine, for men and animals, in the territories of the Hellenic kings:

Everywhere within Beloved-of-the-Gods, King Piyadasi's [Ashoka's] domain, and among the people beyond the borders, the

Pandyas, the Satiyaputras, the Keralaputras, as far as Tamraparni and where the Greek king Antiochus rules, and among the kings who are neighbors of Antiochos, everywhere has Beloved-of-the-Gods, King Piyadasi, made provision for two types of medical treatment: medical treatment for humans and medical treatment for animals. Wherever medical herbs suitable for humans or animals are not available, I have had them imported and grown. Wherever medical roots or fruits are not available I have had them imported and grown. Along roads I have had wells dug and trees planted for the benefit of humans and animals.[26]

Alternatively, the Greek king mentioned in the Edict of Ashoka could also be Antiochus's son and successor, Antiochus II Theos, although the proximity of Antiochus I with the East may makes him a better candidate.[24]

Neoclassical art

The love between Antiochus and his stepmother Stratonice was often depicted in Neoclassical art, as in a painting by Jacques-Louis David.

References

- ^ "Antiochus Cylinder - Livius". www.livius.org.

- ISBN 978-1-107-60572-5.

- ^ "Antiochus I Soter". Livius.

- ISSN 0075-4269.

- ^ "Antiochus I Soter | Seleucid king". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2021-07-25.

- ^ "Antiochus I Soter - Livius". www.livius.org. Retrieved 2021-07-25.

- ISBN 0-89356-313-7.

- ISBN 90-04-08612-9.

- ^ Arrian, Anabasis 7.4.6

- ^ a b c d e One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Seleucid Dynasty s.v. Antiochus I. Soter". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 24 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 604.

- ^ Shahbazi, A. Sh. "Apama". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- ^ Plutarch, Demetrius, 38 gives the most famous account of this tale. See also Appian, Syr. IX.59

- ^ "BCHP 6 (Ruin of Esagila Chronicle)". Livius.

- ISBN 9781107010765.

- ISBN 9781107244566.

- ^ "Antiochus cylinder". British Museum.

- ^ Wallis Budge, Ernest Alfred (1884). Babylonian Life and History. Religious Tract Society. p. 94.

- ^ Oelsner, Joachim (2000). "Hellenization of the Babylonian Culture?" (PDF). The Melammu Project. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ Smith, Andrew. "Johannes Malalas - translation". www.attalus.org. Retrieved 2017-06-06.

- .

- S2CID 194685024.

- ^ Kosmin 2014, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Mookerji 1988, p. 38.

- ^ Antiochus I, with stronger connections in the East.

- ^ Translation of Jarl Charpentier 1931:303–321.

- ^ Edicts of Ashoka, 2nd Rock Edict.

Bibliography

- ISBN 978-0-674-72882-0

- ISBN 81-208-0433-3

- Traver, Andrew G. (2002). From Polis to Empire, the Ancient World, c. 800 B.C.-A.D. 500: A Biographical Dictionary. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780313309427. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

External links

Media related to Antiochus I at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Antiochus I at Wikimedia Commons- Appianus' Syriaka Archived 2015-11-19 at the Wayback Machine

- Antiochus I Soter Archived 2016-10-19 at the Livius.org

- Babylonian Chronicles of the Hellenic Period Archived 2012-10-01 at the Wayback Machine

- Antiochus I Soter entry in historical sourcebook by Mahlon H. Smith

- Hellenization of the Babylonian Culture?

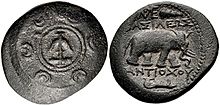

- Coins of Antiochus I