Antithrombin

| SERPINC1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Gene ontology | |||

| Molecular function | |||

| Cellular component | |||

| Biological process |

| ||

| Sources:Amigo / QuickGO | |||

Ensembl | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UniProt | |||||||||

| RefSeq (mRNA) | |||||||||

| RefSeq (protein) | |||||||||

| Location (UCSC) | Chr 1: 173.9 – 173.92 Mb | Chr 1: 160.81 – 160.83 Mb | |||||||

| PubMed search | [3] | [4] | |||||||

| View/Edit Human | View/Edit Mouse |

Antithrombin (AT) is a small

Structure

Antithrombin is also termed antithrombin III (AT III). The designations antithrombin I through to antithrombin IV originate in early studies carried out in the 1950s by Seegers, Johnson and Fell.[7]

Antithrombin I (AT I) refers to the binding of

Antithrombin has a half-life in blood plasma of around 3 days.[9]

The normal antithrombin concentration in human blood plasma is high at approximately 0.12 mg/ml, which is equivalent to a molar concentration of 2.3 μM.[10]

Antithrombin has been isolated from the plasma of a large number of species additional to humans.

Antithrombin begins in its native state, which has a higher free energy compared to the latent state, which it decays to on average after 3 days. The latent state has the same form as the activated state - that is, when it is inhibiting thrombin. As such it is a classic example of the utility of kinetic vs thermodynamic control of protein folding.

Function

Antithrombin is a

The physiological target

Protease inactivation results as a consequence of trapping the protease in an equimolar complex with antithrombin in which the active site of the protease enzyme is inaccessible to its usual

It is thought that protease enzymes become trapped in inactive antithrombin-protease complexes as a consequence of their attack on the reactive bond. Although attacking a similar bond within the normal protease substrate results in rapid

The rate of antithrombin's inhibition of protease activity is greatly enhanced by its additional binding to heparin, as is its inactivation by neutrophil elastase.[23]

Antithrombin and heparin

Antithrombin inactivates its physiological target enzymes, Thrombin, Factor Xa and Factor IXa with

AT-III binds to a specific pentasaccharide sulfation sequence contained within the heparin polymer

GlcNAc/NS(6S)-GlcA-GlcNS(3S,6S)-IdoA(2S)-GlcNS(6S)

Upon binding to this pentasaccharide sequence, inhibition of protease activity is increased by heparin as a result of two distinct mechanisms.

Allosteric activation

Increased Factor IXa and Xa inhibition requires the minimal heparin pentasaccharide sequence. The conformational changes that occur within antithrombin in response to pentasaccharide binding are well documented.[18][31][32]

In the absence of heparin, amino acids P14 and P15 (see Figure 3) from the reactive site loop are embedded within the main body of the protein (specifically the top of

The conformational change most relevant for Factor IXa and Xa inhibition involves the P14 and P15 amino acids within the N-terminal region of the reactive site loop (circled in Figure 4 model B). This region has been termed the hinge region. The conformational change within the hinge region in response to heparin binding results in the expulsion of P14 and P15 from the main body of the protein and it has been shown that by preventing this conformational change, increased Factor IXa and Xa inhibition does not occur.[30] It is thought that the increased flexibility given to the reactive site loop as a result of the hinge region conformational change is a key factor in influencing increased Factor IXa and Xa inhibition. It has been calculated that in the absence of the pentasaccharide only one in every 400 antithrombin molecules (0.25%) is in an active conformation with the P14 and P15 amino acids expelled.[30]

Non-allosteric activation

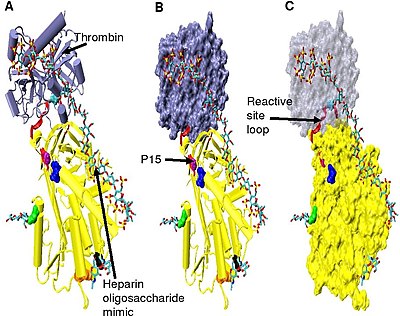

Increased thrombin inhibition requires the minimal heparin pentasaccharide plus at least an additional 13 monomeric units.[33] This is thought to be due to a requirement that antithrombin and thrombin must bind to the same heparin chain adjacent to each other. This can be seen in the series of models shown in Figure 5.

In the structures shown in Figure 5 the C-terminal portion (P' side) of the reactive site loop is in an extended conformation when compared with other un-activated or heparin activated antithrombin structures.[34] The P' region of antithrombin is unusually long relative to the P' region of other serpins and in un-activated or heparin activated antithrombin structures forms a tightly hydrogen bonded β-turn. P' elongation occurs through the breaking of all hydrogen bonds involved in the β-turn.[34]

The hinge region of antithrombin in the Figure 5 complex could not be modelled due to its conformational flexibility, and amino acids P9-P14 are not seen in this structure. This conformational flexibility indicates an equilibrium may exist within the complex between a P14 P15 reactive site loop inserted antithrombin conformation and a P14 P15 reactive site loop expelled conformation. In support of this, analysis of the positioning of P15 Gly in the Figure 5 complex (labelled in model B) shows it to be inserted into beta sheet A (see model C).[34]

Effect of glycosylation on activity

α-Antithrombin and β-antithrombin differ in their affinity for heparin.[35] The difference in dissociation constant between the two is threefold for the pentasaccharide shown in Figure 3 and greater than tenfold for full length heparin, with β-antithrombin having a higher affinity.[36] The higher affinity of β-antithrombin is thought to be due to the increased rate at which subsequent conformational changes occur within the protein upon initial heparin binding. For α-antithrombin, the additional glycosylation at Asn-135 is not thought to interfere with initial heparin binding, but rather to inhibit any resulting conformational changes.[35]

Even though it is present at only 5–10% the levels of α-antithrombin, due to its increased heparin affinity, it is thought that β-antithrombin is more important than α-antithrombin in controlling thrombogenic events resulting from tissue injury. Indeed, thrombin inhibition after injury to the aorta has been attributed solely to β-antithrombin.[37]

Deficiencies

Evidence for the important role antithrombin plays in regulating normal blood coagulation is demonstrated by the correlation between

Acquired antithrombin deficiency

Acquired antithrombin deficiency occurs as a result of three distinctly different mechanisms. The first mechanism is increased excretion which may occur with renal failure associated with proteinuria

Inherited antithrombin deficiency

The incidence of inherited antithrombin deficiency has been estimated at between 1:2000 and 1:5000 in the normal population, with the first family suffering from inherited antithrombin deficiency being described in 1965.[40][41] Subsequently, it was proposed that the classification of inherited antithrombin deficiency be designated as either type I or type II, based upon functional and immunochemical antithrombin analyses.[42] Maintenance of an adequate level of antithrombin activity, which is at least 70% that of a normal functional level, is essential to ensure effective inhibition of blood coagulation proteases.[43] Typically as a result of type I or type II antithrombin deficiency, functional antithrombin levels are reduced to below 50% of normal.[44]

Type I antithrombin deficiency

Type I antithrombin deficiency is characterized by a decrease in both antithrombin activity and antithrombin concentration in the blood of affected individuals. Type I deficiency was originally further divided into two subgroups, Ia and Ib, based upon heparin affinity. The antithrombin of subgroup Ia individuals showed a normal affinity for heparin while the antithrombin of subgroup Ib individuals showed a reduced affinity for heparin.[45] Subsequent functional analysis of a group of 1b cases found them not only to have reduced heparin affinity but multiple or 'pleiotrophic' abnormalities affecting the reactive site, the heparin binding site and antithrombin blood concentration. In a revised system of classification adopted by the Scientific and Standardization Committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis, type Ib cases are now designated as type II PE, Pleiotrophic effect.[46]

Most cases of type I deficiency are due to point mutations, deletions or minor insertions within the antithrombin gene. These genetic mutations result in type I deficiency through a variety of mechanisms:

- Mutations may produce unstable antithrombins that either may be not exported into the blood correctly upon completion biosynthesis or exist in the blood for a shortened period of time, e.g., the deletion of 6 codons 106–108.[47]

- Mutations may affect mRNAprocessing of the antithrombin gene.

- Minor insertions or deletions may lead to frame shiftmutations and premature termination of the antithrombin gene.

- Point mutations may also result in the premature generation of a termination or stop codon e.g. the mutation of codon 129, CGA→TGA (UGA after transcription), replaces a normal codon for arginine with a termination codon.[48]

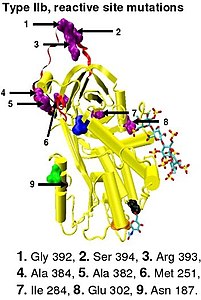

Type II antithrombin deficiency

Type II antithrombin deficiency is characterized by normal antithrombin levels but reduced antithrombin activity in the blood of affected individuals. It was originally proposed that type II deficiency be further divided into three subgroups (IIa, IIb, and IIc) depending on which antithrombin functional activity is reduced or retained.[45]

- Subgroup IIa - Decreased thrombin inactivation, decreased factor Xa inactivation and decreased heparin affinity.

- Subgroup IIb - Decreased thrombin inactivation and normal heparin affinity.

- Subgroup IIc - Normal thrombin inactivation, normal factor Xa inactivation and decreased heparin affinity.

In the revised system of classification again adopted by the Scientific and Standardization Committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis, type II antithrombin deficiency remains subdivided into three subgroups: the already mentioned type II PE, along with type II RS, where mutations effect the reactive site and type II HBS, where mutations effect the antithrombin heparin binding site.[46] For the purposes of an antithrombin mutational database compiled by members of the Plasma Coagulation Inhibitors Subcommittee of the Scientific and Standardization Committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis, type IIa cases are now classified as type II PE, type IIb cases as type II RS and type IIc cases as type II HBS.[49]

Toponyms

Presently it is relatively easy to characterise a specific antithrombin genetic mutation. However prior to the use of modern characterisation techniques investigators named mutations for the town or city where the individual suffering from the deficiency resided i.e. the antithrombin mutation was designated a

Medical uses

Antithrombin is used as a

It is approved by the FDA as an anticoagulant for the prevention of clots before, during, or after surgery or birthing in patients with hereditary antithrombin deficiency.[51][53]

It has been studied in

Cleaved and latent antithrombin

Cleavage at the reactive site results in entrapment of the thrombin protease, with movement of the cleaved reactive site loop together with the bound protease, such that the loop forms an extra sixth strand in the middle of beta sheet A. This movement of the reactive site loop can also be induced without cleavage, with the resulting crystallographic structure being identical to that of the physiologically latent conformation of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1).[55] For this reason the conformation of antithrombin in which the reactive site loop is incorporated uncleaved into the main body of the protein is referred to as latent antithrombin. In contrast to PAI-1 the transition for antithrombin from a normal or native conformation to a latent conformation is irreversible.

Native antithrombin can be converted to latent antithrombin (L-antithrombin) by heating alone or heating in the presence of

The 3-dimensional structure of native antithrombin was first determined in 1994.[31][32] Unexpectedly the protein crystallized as a heterodimer composed of one molecule of native antithrombin and one molecule of latent antithrombin. Latent antithrombin on formation immediately links to a molecule of native antithrombin to form the heterodimer, and it is not until the concentration of latent antithrombin exceeds 50% of the total antithrombin that it can be detected analytically.[59] Not only is the latent form of antithrombin inactive against its target coagulation proteases, but its dimerisation with an otherwise active native antithrombin molecule also results in the native molecules inactivation. The physiological impact of the loss of antithrombin activity either through latent antithrombin formation or through subsequent dimer formation is exacerbated by the preference for dimerisation to occur between heparin activated β-antithrombin and latent antithrombin as opposed to α-antithrombin.[59]

A form of antithrombin that is an intermediate in the conversion between native and latent forms of antithrombin has also been isolated and this has been termed prelatent antithrombin.[60]

Antiangiogenic antithrombin

References

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000117601 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000026715 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-306-45698-5.

- S2CID 22500786.

- PMID 13124503.

- PMID 4102937.

- S2CID 22494710.

- PMID 6667903.

- PMID 6607710.

- ^ S2CID 28872063.

- S2CID 35438503.

- PMID 3473488.

- PMID 2592368.

- PMID 1995647.

- PMID 7646463.

- ^ PMID 10966821.

- PMID 6035483.

- PMID 11389142.

- PMID 982345.

- S2CID 40067251.

- ^ PMID 8670081.

- ^ PMID 12846563.

- ^ PMID 6448846.

- PMID 7085630.

- PMID 2007588.

- ^ PMID 1618758.

- PMID 16973611.

- ^ PMID 15326167.

- ^ S2CID 39110624.

- ^ PMID 8087553.

- S2CID 4339441.

- ^ S2CID 28790576.

- ^ PMID 12581643.

- PMID 9184148.

- PMID 8857927.

- PMID 9241705.

- S2CID 46971091.

- PMID 8813337.

- S2CID 42594050.

- S2CID 38459609.

- PMID 1469094.

- PMID 7937056.

- ^ PMID 6724355.

- ^ S2CID 43884122.

- PMID 8486379.

- PMID 1808766.

- ^ a b Imperial College London, Faculty of Medicine, Antithrombin Mutation Database. Retrieved on 2008-08-16.

- PMID 1421387.

- ^ a b "Thrombate III label" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-11-15. Retrieved 2013-02-23.

- ^ FDA website for ATryn (BL 125284)

- ^ a b Antithrombin (Recombinant) US Package Insert ATryn for Injection February 3, 2009

- PMID 26862016.

- S2CID 4365370.

- S2CID 21583152.

- PMID 9335576.

- S2CID 21452323.

- ^ PMID 10552948.

- PMID 11278631.

- S2CID 260321466.

- PMID 10489375.

Further reading

- Panzer-Heinig, Sabine (2009). Antithrombin (III) - Establishing Pediatric Reference Values, Relevance for DIC 1992 versus 2007 (Thesis). Medizinische Fakultät Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin.

External links

- The MEROPS online database for peptidases and their inhibitors: I04.018 Archived 2019-10-16 at the Wayback Machine

- Antithrombin+III at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Human SERPINC1 genome location and SERPINC1 gene details page in the UCSC Genome Browser.