Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry | |

|---|---|

Occupied France | |

| Occupation | Aviator, writer |

| Education | Villa St. Jean International School |

| Genre | Autobiography, belles-lettres, essays, children's literature |

| Notable awards |

|

| Spouse | |

| Signature | |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ |

|

| Years of service |

|

| Rank | Commander |

| Unit |

|

| Battles/wars | World War II |

| Awards |

|

Antoine Marie Jean-Baptiste Roger, comte de Saint-Exupéry,[3] known simply as Antoine de Saint-Exupéry (UK: /ˌsæ̃tɪɡˈzuːpɛri/,[4] US: /-ɡzuːpeɪˈriː/,[5] French: [ɑ̃twan də sɛ̃t‿ɛɡzypeʁi]; 29 June 1900 – c. 31 July 1944), was a French writer, poet, journalist and aviator. He received several prestigious literary awards for his novella The Little Prince (Le Petit Prince) and for his lyrical aviation writings, including Wind, Sand and Stars and Night Flight (Vol de nuit). His works have been translated into many languages.

Saint-Exupéry was a successful commercial pilot before

Saint-Exupéry spent 28 months in the

Youth and aviation

Saint-Exupéry was born in

Saint-Exupéry had three sisters and a younger brother, François, who died at age 15 of

After twice failing his final exams at a preparatory

Later, Saint-Exupéry was reposted to the 34th Aviation Regiment at

By 1926, Saint-Exupéry was flying again. He became one of the pioneers of international

In 1929, Saint-Exupéry was transferred to Argentina, where he was appointed director of the Aeroposta Argentina airline. He lived in Buenos Aires, in the Galería Güemes building. He surveyed new air routes across South America, negotiated agreements, and occasionally flew the airmail as well as search missions looking for downed fliers. This period of his life is briefly explored in Wings of Courage, an IMAX film by French director Jean-Jacques Annaud.[16]

Writing career

Saint-Exupéry's first novella,

The 1931 publication of Night Flight established Saint-Exupéry as a rising star in the literary world. It was the first of his major works to gain widespread acclaim, and it won the prix Femina. The novel mirrored his experiences as a mail pilot and director of the Aeroposta Argentina.[20] That same year, at Grasse, Saint-Exupéry married Consuelo Suncin (née Suncín Sandoval), a once-divorced, once-widowed Salvadoran writer and artist, who Saint-Exupéry described as having possessed a bohemian spirit and a "viper's tongue".

Saint-Exupéry, would leave and then return to his wife many times—he saw her as both his muse, but, over the long term, the source of much of his angst.

Saint-Exupéry continued to write until the spring of 1943, when he left the United States with American troops bound for North Africa in the

Desert crash

On 30 December 1935, at 2:45 am, after 19 hours and 44 minutes in the air, Saint-Exupéry and his mechanic-navigator, André Prévot, crashed in the

Both Saint-Exupéry and Prévot survived the crash, only to face rapid dehydration due to the harsh weather conditions. Their maps were primitive and ambiguous, leaving them with no idea of their location. Their supplies consisted of some grapes, two oranges, a

The pair had only one day's worth of fluids.[30] They both saw mirages and experienced auditory hallucinations, which were quickly followed by more vivid hallucinations. By the second and third days, they were dehydrated to the point that they stopped sweating. On the fourth day, a Bedouin on a camel discovered them and administered a native rehydration treatment that saved their lives.[27] His near-death experience would feature prominently in his 1939 memoir, Wind, Sand and Stars, which won several awards. Saint-Exupéry's classic novella The Little Prince, which begins with a pilot being stranded in the desert, is, in part, a reference to this experience.[31]

Canadian and American sojourn and The Little Prince

Following the

After

Between January 1941 and April 1943, the Saint-Exupérys lived in New York City's

Saint-Exupéry and

Saint-Exupéry added the hyphen to his surname after his arrival in the United States, stating that he was annoyed with Americans addressing him as "Mr. Exupéry".[3] During this period, he authored Pilote de guerre (Flight to Arras), which earned widespread acclaim, and Lettre à un otage (Letter to a Hostage), dedicated to the 40 million French living under Nazi oppression, in addition to numerous shorter pieces in support of France. The Saint-Exupérys also resided in Quebec City, Canada for several weeks during the late spring of 1942. During their time in Quebec City, the family lived with the philosopher Charles De Koninck and his family, including his "precocious" 8 year old son, Thomas.[43][44][Note 4]

After he returned from his stay in Québec, which had been fraught with illness and stress, the wife of one of his publishers helped persuade Saint-Exupéry to produce a children's book,

Return to war

In April 1943, following his 27 months in North America, Saint-Exupéry departed with an American military convoy for

Saint-Exupéry was assigned with a number of other pilots to his former unit, renamed Groupe de reconnaissance 2/33 "Savoie", flying

After Saint-Exupéry resumed flying, he also returned to his longtime habit of reading and writing while flying his single-seat

Disappearance

Before his return to flight duty with his squadron in North Africa, the collaborationist

Saint-Exupéry's last reconnaissance mission was to collect intelligence on German troop movements in and around the

Discovery at sea

In September 1998, to the east of Riou Island (south of Marseille), a fisherman found a silver identity bracelet bearing the names of Saint-Exupéry, his wife Consuelo, and his American publisher, Reynal & Hitchcock.[61] The bracelet was hooked to a piece of fabric, presumably from his flight suit.[24] Announcement of the discovery was an emotional event in France, where Saint-Exupéry was a national icon, and some disputed its authenticity because it was found far from his intended flight path, implying that the aircraft might not have been shot down.[62]

In May 2000 a diver found debris from a Lockheed P-38 Lightning submerged off the coast of Marseille, near where the bracelet was found. The discovery galvanized the country, which had conducted searches for his aircraft and speculated on Saint-Exupéry's fate for decades.[63] After a two-year delay imposed by the French government, the remnants of the aircraft were recovered in October 2003.[61][Note 10] In 2004, French officials and investigators from the French Underwater Archaeological Department officially confirmed that the wreckage was from Saint-Exupéry's aircraft.[63][65]

No marks or holes attributable to gunfire were found, but that was not considered significant as only a small portion of the aircraft was recovered.

Speculations in 1948, 1972 and 2008

In 1948, former Luftwaffe telegrapher Rev. Hermann Korth published his war logs, noting an incident that occurred at around noon on 31 July 1944 in which a Focke-Wulf Fw 190 shot down a P-38 Lightning. Korth's account ostensibly supported a shoot-down hypothesis for Saint-Exupéry.[68][69] The veracity of his log was met with skepticism, because it could have described a P-38 which was flown by Second Lieutenant Gene Meredith on 30 July, shot down south of Nice.[68][70][Note 11]

In 1972, the German magazine Der Landser quoted a letter from Luftwaffe reconnaissance pilot Robert Heichele, in which he purportedly claimed to have shot down a P-38 on 31 July 1944.[72] His account, corroborated by a spotter, seemingly supported a shoot-down hypothesis of Saint-Exupéry.[73] Heichele's account was met with skepticism, because he described flying a Focke-Wulf Fw 190 D-9, a variant which had not yet entered Luftwaffe service.[74]

In the lists which are held by the Bundesarchiv-Militärarchiv, no victory was credited to Heichele or his unit in either July or August 1944, and the decrypted report of the day's reconnaissance does not include any flights by 2./NAG 13's Fw 190s.[75] Heichele was shot down on 16 August 1944 and died five days later.[Note 12][76]

In 2008, a French journalist from La Provence, who was investigating Saint-Exupéry's death, contacted former Luftwaffe pilots who flew in the area of Marseille, eventually getting an account from Horst Rippert (1922–2013).[66][77][78] Rippert was the older brother of the famous bass singer Ivan Rebroff, who was born in Berlin as Hans-Rolf Rippert. In his memoirs, Horst Rippert, an admirer of Saint-Exupéry's books, expressed both fears and doubts that he was responsible, but in 2003 he stated that he became certain that he was responsible when he learned the location of Saint-Exupéry's wreckage.[79] Rippert claimed to have reported the kill over his radio, but there are no surviving records to verify this account.[69][70][Note 13][Note 14]

Rippert's account, as it is discussed in two French and German books, was met with both publicity and skepticism.[81][82] Luftwaffe comrades expressed doubts in Rippert's claim, given that he held it private for 64 years.[83][84][Note 15] Very little German documentation survived the war, and contemporary archival sources, consisting mostly of Allied intercepts of Luftwaffe signals, offer no evidence to verify Rippert's claim.[85][86] The entry and exit points of Saint-Exupéry's mission were likely near Cannes, yet his wreckage was discovered south of Marseille.[80]

Though it is possible that German fighters could have intercepted, or at least altered, Saint-Exupéry's flight path, the cause of his death remains unknown, and Rippert's account remains one hypothesis among many.[70][80][87][Note 16]

Literary works

While not precisely autobiographical, much of Saint-Exupéry's work is inspired by his experiences as a pilot. One notable example is his novella, The Little Prince, a poetic tale self-illustrated in watercolours in which a pilot stranded in the desert meets a young prince fallen to Earth from a tiny asteroid. "His most popular work, The Little Prince was partially based upon a crash he and his navigator survived in the Libyan desert. They were stranded and dehydrated for four days, nearing death when they miraculously stumbled upon a Bedouin who gave them water.[89] Saint-Exupéry would later write in Wind, Sand and Stars that the Bedouin saved their lives and gave them "charity and magnanimity [by] bearing the gift of water."[90] The Little Prince is a philosophical story, including societal criticism, remarking on the strangeness of the adult world. One biographer wrote of his most famous work: "Rarely have an author and a character been so intimately bound together as Antoine de Saint-Exupéry and his Little Prince," and remarking of their dual fates, "...the two remain tangled together, twin innocents who fell from the sky."[24]

Saint-Exupéry's notable literary works (published English translations in parentheses) include:[91]

- L'Aviateur (1926) (The Aviator, in the anthology A Sense of Life)

- Southern Mail) – made as a movie in French

- Vol de nuit (1931) (Night Flight) – winner of the full prix Femina and made twice as a movie and a TV film, both in English

- The Wild Garden (1938) – Limited to one thousand copies privately printed for the friends of the author and his publishers as a New Year's Greeting. The story is taken from the forthcoming book, Wind, Sand and Stars, to be published in the spring of 1939.

- Terre des hommes (1939) – winner of the Grand Prix du roman de l'Académie française

- Wind, Sand and Stars (simultaneous distinct English version)[Note 17] – winner of the U.S. National Book Award[92][93]

- Pilote de guerre (1942) (titled in English as: Flight to Arras) – winner of the Grand Prix Littéraire de l'Aéro-Club de France[94]

- top four selling books in the world;[95] made as both movies and TV films in a number of languages, and adapted to numerous other mediain many languages

- Lettre à un otage (1944) (Letter to a Hostage, posthumous in English)[96]

Published posthumously

- Citadelle (1948) (titled in English: as The Wisdom of the Sands) – winner of the Prix des Ambassadeurs

- Lettres à une jeune fille (1950)

- Lettres de jeunesse, 1923–1931 (1953)

- Lettres à l'amie inventée (1953)[97]

- Carnets (1953)

- Lettres à sa mère (1955)

- Un sens à la vie (1956), (A Sense of Life)[98][99][Note 18]

- Lettres de Saint-Exupéry (1960)

- Lettres aux américains (1960)

- Écrits de guerre, 1939–1944 (1982) (Wartime Writings, 1939–1944)

- Manon, danseuse (2007)

- Lettres à l'inconnue (1992)

Other works

During the 1930s, Saint-Exupéry led a mixed life as an aviator, journalist, author and publicist for

Notable among those during World War II was "An Open Letter to Frenchmen Everywhere", which was highly controversial in its attempt to rally support for France against Nazi oppression at a time when the French were sharply divided between support of the

- "Une Lettre de M. de Saint-Exupéry", Les Annales politiques et littéraires, 15 December 1931; (extracts from a letter written to Benjamin Crémieux).

- Preface of Destin de Le Brix by José le Boucher, Nouvelle Librairie Française, 1932.

- Preface of Grandeur et servitude de l'aviation by Maurice Bourdet, Paris: Editions Corrêa, 1933.

- "Reflections on War", translated from Living Age, November 1938, pp. 225–228.

- Preface of Vent se lève (French translation of Listen! The Wind) by Anne Morrow Lindbergh, Paris: Editions Corrêa, 1939.[Note 19]

- Preface of Pilotes d'essai by Jean-Marie Conty, Paris: Edition Spes, 1939.

- "Books I Remember", Harper's Bazaar, April 1941.

- "Letter to Young Americans", The American High School Weekly, 25 May 1942, pp. 17–18.

- "Voulez-vous, Français, vous reconcilier?", Le Canada, de Montreal, 30 November 1942.

- "L'Homme et les éléments", Confluences, 1947, Vol. VII, pp. 12–14 (issue dedicated to Saint-Exupéry; originally published in English in 1939 as 'The Elements' in Wind, Sand and Stars).

- "Lettre Inédite au General C", Le Figaro Littéraire, 10 April 1948 (posthumous).

- "Seigneur Berbère", La Table Ronde, No. 7, July 1948 (posthumous).

Censorship and publication bans

Pilote de guerre (Flight To Arras), which describes the German invasion of France, was slightly censored when it was released in its original French during wartime by

In support of their German occupiers and masters, Vichy authorities attacked the author as a defender of

A further complication occurred due to Saint-Exupéry's and others' view of General

Extension of copyrights in France

Due to Saint-Exupéry's wartime death, the French government awarded his estate the

Honours and legacy

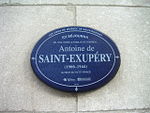

- Images of remembrance

-

Commemorative inscription in thePanthéon of Paris

-

Portrait and images from The Little Prince on a 50-franc banknote

-

Historical marker where the Saint-Exupérys resided in Quebec

- Saint-Exupéry is commemorated with an inscription in the Chevalier de la Légion d'honneur in April 1930 and was promoted to Officier de la Légion d'honneur in January 1939. He was awarded the Croix de Guerre in 1940 and was posthumously awarded the Croix de Guerre avec Palme in 1944.[citation needed]

- From 1993 until the introduction of the euro, Saint-Exupéry's portrait and several of his drawings from The Little Prince appeared on France's 50-franc banknote.[24] The French Government also later minted a 100-franc commemorative coin, with Saint-Exupéry on its obverse side, and the Little Prince on its reverse. Brass-plated souvenir Monnaie de Paris commemorative medallions were also created in his honour, depicting the pilot's portrait over the P-38 Lightning aircraft he last flew.

- In 1999, the Government of Quebec and Quebec City added a historical marker to the family home of Charles De Koninck, head of the Department of Philosophy at Université Laval, where the Saint-Exupérys stayed while lecturing in Canada for several weeks during May and June 1942.[citation needed]

- In 2000, on the centenary of his birth, in the city where he was born, he was memorialised when the Lyon Satolas Airport was renamed the Gare de Lyon Saint-Exupéry. The author is additionally commemorated by a statue in Lyon, depicting a seated Saint-Exupéry with the little prince standing behind him.[citation needed]

- A street in Montesson, a suburb of Paris, is named for him as Rue Antoine de Saint-Exupéry.[citation needed]

Museums and exhibits

Museum exhibits, exhibitions and theme villages dedicated to both him and his diminutive Little Prince have been created in Le Bourget, Paris and other locations in France, as well as in the Republic of South Korea, Japan, Morocco, Brazil, the United States and Canada:[citation needed]

- The Le Bourget Airport, in cooperation with The Estate of Saint-Exupéry-d'Agay, has created a permanent exhibit of 300 m2 dedicated to the author, pilot, person and humanist. The Espace Saint-Exupéry exhibit, officially inaugurated in 2006 on the anniversary of the aviator's birthday,[106] traces each stage of his life as an airmail pioneer, eclectic intellectual artist, and military pilot. It includes artifacts from his life: photographs, his drawings, letters, some of his original notebooks (carnets) he scribbled in voluminously and which were later published posthumously, plus remnants of the unarmed P-38 he flew on his last reconnaissance mission and which were recovered from the Mediterranean Sea.[107]

- In Tarfaya, Morocco, next to the Cape Juby airfield where Saint-Exupéry was based as an Aéropostale airmail pilot/station manager, Antoine de Saint-Exupery Museum was created honouring both him and the company. A small monument at the airfield is also dedicated to them.[citation needed]

- In Gyeonggi-do, South Korea, and Hakone, Japan, theme village museums have been created honouring Saint-Exupéry's Little Prince.

- In January 1995, the Alberta Aviation Museum of Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, in conjunction with the cultural organization Alliance française, presented a showing of Saint-Exupéry letters, watercolours, sketches and photographs.[108]

- In São Paulo, Brazil, through 2009, the Oca Art Exhibition Centre presented Saint-Exupéry and The Little Prince as part of The Year of France and The Little Prince. The displays covered over 10,000 m2 on four floors, and chronicled Saint-Exupéry, The Little Prince and their philosophies, as visitors passed through theme areas of the desert, asteroids, stars, and the cosmos. The ground floor of the giant exhibition was laid out as a huge map of the routes flown by the author with Aeropostale in South America and around the world. Also included was a full-scale replica of the author's crashed Caudron Simoun, lying wrecked on the ground of a simulated Libyan desert following his disastrous Paris-Saigon race attempt. The miraculous survival of Saint-Exupéry and his mechanic/navigator was subsequently chronicled in the award-winning memoir Wind, Sand and Stars (Terre des hommes), and also formed the introduction of his most famous work The Little Prince (Le Petit Prince).[109]

- In 2011, the City of Toulouse, France, home of Airbus and the pioneering airmail carrier Aéropostale, in conjunction with the Estate of Saint-Exupéry-d'Agay and the Youth Foundation of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, hosted a major exposition on Saint-Exupéry and his experience with Aéropostale. The exposition, titled L'année Antoine de Saint-Exupéry à Toulouse, exhibited selected personal artifacts of the author-aviator, including gloves, photos, posters, maps, manuscripts, drawings, models of the aircraft he flew, some of the wreckage from his Sahara Desert plane crash, and the personal silver identification bracelet engraved with his and Consuelo's name, presented by his U.S. publisher, which was recovered from his last, ultimate crash site in the Mediterranean Sea.[110]

- On 27 February 2012, Russia's Sorbonne professor of Slavic languages, who addressed the audience by video link from Paris.[111]

- A number of other prominent exhibitions were created in France and the United States, many of them in 2000, honouring the centenary of the author-aviator's birth.

- In January 2014, New York City's Morgan Library & Museum featured a major three-month-long exhibition, The Little Prince: A New York Story. Celebrating the 70th anniversary year of the novella's publication, its exhibits included many of Saint-Exupéry's original manuscript pages, his story's preliminary drawings and watercolor paintings, and also examined Saint-Exupéry's creative writing processes.[112][113][114][115][116]

International

- Saint-Exupéry's 1939 memoir 1967 International and Universal Exposition in Montreal, Quebec, Canada (Expo '67), the most successful world's fair of the 20th century. The central theme, which also generated the 17 subsidiary elements used for the world's fair, was elucidated at a 1963 Montebello, Quebec, conference held with some of Canada's leading thinkers. At Montebello, French-Canadian author Gabrielle Roy helped choose the central theme by quoting Saint-Exupéry on mankind's place in the universe:[citation needed]

"Être homme, c'est précisément être responsable. C'est sentir, en posant sa pierre, que l'on contribue à bâtir le monde" (to be a man is to be responsible, to feel that by laying one's own stone, one contributes to building the world)

- Additionally, Michèle Lalonde and André Prévost's oratorio Terre des hommes, performed at the Place des Nations opening ceremonies and attended by the international delegates of the participating countries, strongly projected the French writer's 'idealist rhetoric'. Consuelo de Saint-Exupéry (1901–1979), his widow, was also a guest of honour at the opening ceremonies of the world's fair.[117]

- Asteroid 2578 Saint-Exupéry, discovered in November 1975 by Russian astronomer Tamara Smirnova and provisionally cataloged as Asteroid 1975 VW3, was renamed in the author-aviator's honour.[118] Another asteroid was named as 46610 Bésixdouze (translated to and from both hexadecimal and French as 'B612').[119] Additionally the terrestrial-asteroid protection organization B612 Foundation was named in tribute to the author's Little Prince, who fell to Earth from Asteroid B-612.[120][121][122][123]

- Philatelic tributes have been printed in at least 25 other countries as of 2011[update].[124] Only three years after his death, the pilot-aviator was first featured on an 8 franc French West Africa airmail stamp (Scott Catalog # C11). France followed several months later in 1948 with an 80 franc airmail stamp honouring him (CB1), and later with another stamp honouring both him and airmail pioneer Jean Mermoz, plus the supersonic Concorde passenger airliner, in 1970 (C43).[124] In commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the writer's death, Israel issued a stamp honoring "Saint-Ex" and The Little Prince in 1994.[125]

- In Argentina and Brazil, where Saint-Exupéry became the founding director of the pioneering South American airmail airline Aeroposta Argentina:

- the Cerro Chaltén (also known as Monte Fitz Roy) in the Los Glaciares National Park in Patagonia, Argentina, The mountain peak is named in Saint-Exupéry's honour;[citation needed]

- the San Antonio Oeste municipal airport was named Aerodromo Saint Exupery.[126] A small museum exhibit resides in the airport building;

- the small Brazilian airport serving Ocauçu, São Paulo is named after the pilot, and[citation needed]

- several Argentinian schools are also named after the author-aviator.[citation needed]

- the

The main street of the town of Campeche on the Ilha da Santa Catarina (where florianopolis the capital the state is also situated), is named avenida principe pequeno because of his connection to the region.

Institutions and schools

- In 1960 the humanitarian organization Terre des hommes, named after Saint-Exupéry's 1939 philosophical memoir Terre des hommes (titled as Wind, Sand and Stars in English),[127] was founded in Lausanne, Switzerland by Edmond Kaiser. Other Terre des Hommes societies were later organized in more countries with similar social aid and humanitarian goals. The several independent groups joined to form a new umbrella organization, Terre des Hommes-Fédération Internationale (TDHFI, in English: International Federation of Terre des Hommes, or IFTDH). The national constituents first met in 1966 to formalize their new parent organization, headquartered in Geneva, Switzerland. As of 2009[update] eleven organizations in Canada, Denmark, Germany, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Spain, Switzerland, and Syria belonged to the Federation. An important part of their works is their consulting role to the United Nations Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC).[128]

- In June 2009, the Antoine de Saint-Exupéry Youth Foundation (FASEJ) was founded in Paris by the Saint-Exupéry–d'Agay Estate, to promote education, art, culture, health and sports for youth worldwide, especially those from disadvantaged backgrounds. This organization, which follows Saint-Exupéry's philosophies and his memory, was financed in part by the sale of one of his original 1936 handwritten manuscripts at a Sotheby's auction for €312,750.[129][130]

- Numerous public schools, lycées, high schools, colleges and technical schools have been named in honour of Saint-Exupéry across France, Europe, Québec and South America, as well as at least two in Africa. The

Other

Numerous other tributes have been awarded to honour Saint-Exupéry and his most famous literary creation, his Little Prince:

- The GR I/33 (later renamed as the 1/33 Belfort Squadron), one of the French Air Force squadrons Saint-Exupéry flew with, adopted the image of the Little Prince as part of the squadron and tail insignia on its Dassault Mirage fighter jets.[133]

- Google celebrated Saint-Exupéry's 110th birthday with a special logotype depicting the little prince being hoisted through the heavens by a flock of birds.[134]

- Numerous streets and place names are named after the author-aviator throughout France and other countries.[citation needed]

- Cafe Saint-Ex, a popular bar and nightclub in Washington, D.C. near the U-Street corridor, holds Saint-Exupéry as its name source.[citation needed]

- Uruguayan airline ATR-72 (CX-JPL), in honor of the aviator.[citation needed]

- International Watch Company (IWC) has created many Saint-Exupéry tribute versions of several of their wristwatch lines, with the distinctive 'A' from his signature featured on the dial.[citation needed]

- The American aviation magazine Flying ranked Saint-Exupéry number 41 on their list of the "51 Heroes of Aviation".[135]

- The French 50-franc banknote depicted Antoine de Saint-Exupéry and had several features that allude to his works.[136]

- The new flagship of CMA CGM Group for celebrating her 40th anniversary, takes the name of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry to commemorate his achievement.[citation needed]

In popular culture

Film

- Wings of Courage is a 1995 docudrama by French director Jean-Jacques Annaud. The movie was the world's first dramatic picture shot in the IMAX format and is an account of the true story of early airmail pilots Henri Guillaumet (played by Craig Sheffer), Saint-Exupéry played by Tom Hulce, and several others.[citation needed]

- Saint-Exupéry and his wife Consuelo were portrayed by Bruno Ganz and Miranda Richardson in the 1997 biopic Saint-Ex, a British film biography of the French author-pilot. It also featured Eleanor Bron and was filmed and distributed in the United Kingdom, with scripting by Frank Cottrell Boyce. The film combines elements of biography, documentary, and dramatic licence.[citation needed]

Literature

- After his disappearance, Consuelo de Saint-Exupéry wrote The Tale of the Rose, which was published in 2000 and subsequently translated into 16 languages.[137]

- Saint-Exupéry is mentioned in Tom Wolfe's The Right Stuff: "A saint in short, true to his name, flying up here at the right hand of God. The good Saint-Ex! And he was not the only one. He was merely the one who put it into words most beautifully and anointed himself before the altar of the right stuff."[citation needed]

- Comic-book author Hugo Pratt imagined the fantastic story of Saint-Exupéry's last flight in Saint-Exupéry: le dernier vol (1994).[citation needed]

- Saint-Exupéry is the subject of the 2013 historical novel Studio Saint-Ex (Knopf, New York / Penguin, Canada) by Ania Szado. In the novel Saint-Exupéry awaits the Americans' entry into World War II, while writing The Little Prince in New York.[citation needed]

- Wind, Sand and Stars is an important book to narrator Theo Decker, who re-reads it often, in The Goldfinch (2013) by Donna Tartt.[citation needed]

- Saint-Exupéry was the principal character in Antonio Iturbe's 2017 Spanish language novel A cielo abierto which was translated into English and published in 2021 with the title The Prince of the Skies.

Music

- Saint-Exupéry's death and speculation that Horst Rippert shot him down are the subject of "Saint Ex", a song on Widespread Panic's eleventh studio album, Dirty Side Down.[citation needed]

- "P 38", a 1983 song by the Swedish pop band Webstrarna took inspiration from Saint-Ex disappearance in July 1944.

- The Norwegian progressive rock band Gazpacho's concept album Tick Tock is based on Saint-Exupéry's desert crash.[citation needed]

- "On the Planet of the Living", a song sung by Eduard Khil, was dedicated to Saint-Exupéry.[citation needed]

- "St. Exupéry Blues" – a song by Russian folk-rock band Melnitsa from their album "Alchemy"[citation needed]

- "Far Side of the World" a song by American singer-songwriter Jimmy Buffett, he mentions both Saint-Exupery and "Wind, Sand and Stars"

Theatre

- In August 2011, Saint-Ex, a theatrical production of Saint-Exupéry's life, premiered in Weston, Vermont.[138]

- Saint-Exupéry appears as one of the 3 historical characters in the one-act play, DINNER @ AMELIA'S ((c) 2019) by Myles A. Garcia, an American playwright. The two other historical characters in the same play are Alberto Santos-Dumont, the Brazilian pioneering aviator, and T.E. Lawrence (the future Lawrence of Arabia).

See also

- List of people who disappeared

General

- Consuelo de Saint-Exupéry, wife of Saint-Exupéry

- Indexed listing of Wikipedia's Saint-Exupéry articles

Literary works in English

- The Aviator

- Southern mail

- Night Flight

- Wind, Sand and Stars

- Flight to Arras

- The Little Prince

- A Sense of Life

Media and popular culture

- List of The Little Prince adaptations

- Saint-Ex, a 1997 British biopic

Notes

- ^ Saint-Exupéry was born at No. 8 rue Peyrat, later rue Alphonse Fochier, and still later renamed rue Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, in Lyon's 2nd arrondissement.[9] He was the third of five children (and nicknamed 'Tonio'), after older sisters Marie-Madeleine ("Biche", 26 January 1897 – 1927), Simone ("Monot", 26 January 1898 – 1978), and his younger siblings François (1902–1917) and Gabrielle ("Didi", 1903–1986). His father and mother were Viscount Jean de Saint-Exupéry (1863–1904; different sources name his father as Jean-Marc or Caesar de Saint-Exupéry[11]) and Viscountess Marie, née Boyer de Fonscolombe (1875–1972). He was baptized in a Catholic ceremony in his great-aunt's chapel on 15 August 1900 in Saint-Maurice-de-Rémens; his godfather was his uncle, Roger de Saint-Exupéry, Earl of Miremont (1865 – August 1914, killed leading his battalion in Maissin, Belgium, during the First World War), and his godmother was his aunt Madeleine Fonscolombe.[10]

- ^

Hélène (Nelly) de Vogüé (1908–2003), born Hélène Jaunez to a French businessman, became a well-known French business executive and also an intellectual fluent in several languages. She married the equally well-known French noble, Jean de Vogüé, in 1927 and had one child with him, a son named Patrice. Hélène is referred to only as "Madame de B." in multiple Saint-Exupéry biographies. This occurred due to agreements she made with writers before granting them access to her troves of the author-aviator's writings, which she deposited in the French national archives—from which they will not be released until 2053. It is believed she sought her anonymity to protect Saint-Exupéry's reputation, as during the collaborator.[23]

- ^

The aircraft Saint-Exupéry was flying when he crashed in the Sahara was a Caudron C.630 Simoun, Serial Number 7042, with the French registration F-ANRY, with 'F' being the international designator for France, and the remainder being derived from 'ANtoine de saint-exupéRY'.

- ^ The large home of Charles De Koninck has since been classified as a historical building and has been visited frequently by numerous worldwide personalities from academic, scientific, intellectual, and political circles. Thomas kept a few memories from Saint-Exupéry's visit: "[He was] a great man. He was the aviator. Someone we would get attached to quite easily, who would show interest in us, the kids. He would make us paper planes, drawings. [...] He loved mathematical enigmas." The following year, he published The Little Prince. According to the local legend, Saint-Exupéry received his inspiration from the junior De Koninck, who asked many questions. However, Thomas De Koninck denied this interpretation: "The Little Prince is Saint-Exupéry himself."

- ^ Although Saint-Exupéry's regular publisher in France, Gallimard, lists Le Petit Prince as being published in 1946, that apparently is a legalistic interpretation possibly designed to allow for an extra year of the novella's copyright protection period and is based on Gallimard's explanation that sales of the book started only in 1946. Other sources, such as the one referenced, depict the first Librairie Gallimard printing of 12,250 copies as occurring on 30 November 1945.[48]

- ^ After being grounded following his crash, Saint-Exupéry spared no efforts in his campaign to return to active combat flying duty. He utilized all his contacts and powers of persuasion to overcome his age and physical handicap barriers, which would have completely barred an ordinary patriot from serving as a war pilot. Instrumental in his reinstatement was an agreement he proposed to John Phillips, a fluently bilingual Life magazine correspondent in February 1944, where Saint-Exupéry committed to "...write, and I'll donate what I do to you, for your publication, if you get me reinstated into my squadron."[53] Phillips later met with a high-level U.S. Army Air Forces press officer in Italy, Colonel John Reagan McCrary, who conveyed the Life magazine request to General Eaker. The approval for return to flying status would be made "...not through favoritism, but through exception". The brutalized French, it was noted, would cut a German's throat "...probably with more relish than anybody".

- ^ Saint-Exupéry suffered recurring pain and immobility from previous injuries due to his five serious aircraft crashes. After his death, they were also vague suggestions that his disappearance was the result of suicide rather than aircraft failure or combat loss.

- ^ Various sources state that his final flight was either his seventh, eight, ninth, and even his tenth mission. He volunteered for almost every proposed mission submitted to his squadron, and protested fiercely after being grounded following his second sortie, which ended with a demolished P-38. Saint-Exupéry's friends, colleagues and compatriots were working to keep him grounded and out of harm's way, but his connections in high places, plus a publishing agreement with Life magazine, were instrumental in having the grounding lifted.[58]

- ^ One ruse contemplated by GR II/33's commanders was to expose Saint-Exupéry "accidentally" to the plans of the pending invasion of France so he could be subsequently grounded. No air force general would countermand such a grounding order and risk Saint-Exupéry's being captured by the Germans if he were forced down. Saint-Exupéry's commanding officer—a close friend of his—was ill and absent when the author took off on his final flight. The commander "bawled out" his staff when he learned that a grounding scheme had not been implemented.

- ^ Saint-Exupéry's P-38, as identified in the wreckage recovery report, was an F-5B-1-LO, LAC 2734 variant, serial number 42-68223, which departed Borgo-Porreta, Bastia, Corsica, France on 31 July 1944, at 8:45 a.m. The report includes an image of a component bearing a serial number which confirmed it came from Saint-Exupéry's aircraft. The size of the debris field—1 km (0.62 mi) long and 400 m (1,300 ft) wide—suggested that the aircraft had struck the water at high velocity.[64]

- 23rd Photographic Squadron/5th Reconnaissance Group. The intercepted Mediterranean Allied Air Forces Signals Intelligence Report for 30 July records that "an Allied reconnaissance aircraft was claimed shot down at 1115 [GMT]". The last estimated position of Meredith's plane is 4307N, 0756E.[71]

- ^ He is buried in the German military cemetery at Dagneux, France.

- ^ The RAF's No. 276 Wing (Signals Intelligence, Allied intercepts of Luftwaffe communications) Operations Record Book for 31 July 1944 notes only: "... three enemy fighter sections between 0758/0929 hours operating in reaction to Allied fighters over Cannes, Toulon and the area to the North. No contacts. Patrol activity north of Toulon reported between 1410/1425 hours".[70]

- ^ In documents OIS 4FG 40 and OP rep 25 (available at SHD / Air), the 4th Fighter Squadron on a sweeping mission from Vercors to Orange, observed two German "bogeys" flying East at 11:30 a.m. Given Saint-Exupéry's fuel reserves and expected mission duration, it is possible that he crossed paths with the German aircraft.[80]

- ^ The proposed "suppression" of Rippert's claim due to Saint-Exupéry's stature was also met with skepticism as Luftwaffe pilots tended to immediately report their kills, and the Allies did not broadcast Saint-Exupéry's status as missing for at least two days.[70] It is feasible that Rippert did not push for an official kill, given that he was flying alone with no spotter to corroborate.[80] After the war, Horst Rippert became a television journalist and led the ZDF sports department. He was the brother of German singer Ivan Rebroff. Rippert died in 2013.

- The Saturday Review of Literature on 14 October 1939.[92]

- ^ The last paragraph of Flying's book review of A Sense of Life incorrectly states that Saint-Exupéry's last mission was a bombing run, when in fact it was a photo-reconnaissance assignment for the pending invasion of Southern France.

- The Saturday Review of Literature on 14 October 1939.[92]

References

Citations

- ^ a b Commire (1980), p. 158.

- ^ Commire (1980), p. 161.

- ^ a b Schiff (2006), p. xi.

- ^ "Saint-Exupéry, Antoine de". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 6 September 2021.

- ^ "Saint-Exupéry". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). HarperCollins. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- ^ Kocis, Desiree (17 December 2019). "Mysteries of Flight: The Disappearance of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry". Plane & Pilot Magazine. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- ^ Acte de naissance numéro 1703, page 158/257, reg. 2E1847, with marginal note concerning his marriage with Consuelo Suncin (Nice, 22 April 1931). Archives municipales numérisées de Lyon.

- ^ a b Webster (1994), p. 12.

- ^ a b Chronology of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. Archived 1 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine AntoinedeSaint-Exupéry.com website. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ^ Commire (1980), p. 154.

- ^ Schiff (2006), p. ix.

- ^ Schiff (1996), pp. 61–62.

- ^ Schiff (1996), p. 80.

- ^ Schiff, Stacy (1994). Saint-Exupéry: A Biography. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

- ^ James, Caryn. "Wings of Courage: High Over the Andes, In Enormous Goggles (1995 Film Review)." The New York Times, 21 April 1995. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

- ^ Actualités: Découverte d'un film en couleur sur Saint Exupéry Archived 4 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine (media release), AntoinedeSaintExupéry.com website (in French). Retrieved 25 September 2011.

- ^ Willsher, Kim. "Haunting Film of Petit Prince Author Saint-Exupéry For Auction." Guardian.uk.co, 9 April 2010. On 10 April 2010, a version appeared in print on p. 31. Revised: 13 April 2010.

- ^ Ibert, Jean-Claude. Antoine de Saint-Exupéry: Classiques de XXe Siècle. Paris: Éditions Universitaires, 1953, p. 123.

- ^ Schiff (1996), p. 210.

- ^ Webster, Paul. "Flying Into A Literary Storm: Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, Author of 'The Little Prince', was born 100 years ago. The Celebrations, however, have been marred by his widow's bitter account of their marriage." The Guardian (London), 24 June 2000.

- ^ "Biography: Nelly de Vogüé (1908–2003)." AntoinedeSaintExupery.com. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- ^ Carrol, Tim. "Secret Love of a Renaissance Man". The Daily Telegraph, 30 April 2007.

- ^ a b c d e Schiff, Stacy. "Bookend: Par Avion." The New York Times, 25 June 2000.

- ^ Antoine de Saint-Exupery. Poems poemhunter.com

- ^ Schiff (1996), p. 258.

- ^ a b Schiff 1994, pp. 256–267.

- ^ Schiff (1996), p. 263.

- ^ Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, Wind, Sand, and Stars, 1939, p127-152

- ^ Schiff (2006), p. 258.

- ^ Kantor |, Emma. "'The Little Prince' Comes of Age". PublishersWeekly.com. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ^ Exiles Memorial Center.

- ^ Saint-Exupéry, A. (1943) Lettre à un Otage, Éditions Brentano's. PDF version Archived 16 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ellis Island Passenger Registration Records.

- ^ Schiff (1996), p. 331.

- ^ "French Flier Gets Book Prize for 1939: Antoine de St. Exupery Able at Last to Receive ..." The New York Times, 15 January 1941, p. 6. via ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The New York Times (1851–2007).

- ^ Saint-Exupéry, Consuelo de, tr. by Woods, Katherine. Kingdom of the Rocks: Memories of Oppède, Random House, 1946.

- ^ Schiff (1996), p. 338.

- ^ Dunning (1989).

- ^ Cotsalas (2000).

- Public Broadcasting Systemwebsite. Retrieved from PBS.org 1 February 2013.

- ^ a b c Milestones, Aug. 14, 1944. Missing in Action: Count Antoine de Saint Exupéry. Time, 14 August 1944. Quote: "Saint Exupery, veteran of over 13,000 flying hours, was grounded last March by a U.S. Army Air Forces officer because of age, was later put back into his plane by a decision of Lieut. General Ira C. Eaker, flew some 15 flak-riddled missions in a P-38 before his disappearance."

- ^ a b Schiff (2006), p. 379.

- ^ Brown (2004).

- ^ Schiff (1996), p. 278.

- ^ a b Severson (2004), p. 166, 171.

- ^ a b c Schiff (1996), p. 366.

- ^ "Le Petit Prince – 1945 – Gallimard." Archived 4 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine LePetitPrince.net website. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

- ^ Saint-Exupéry (1943), Preamble.

- ^ Schiff (2006), p. 180.

- ^ Cate (1970).

- ^ Schiff (2006), p. 423.

- ^ Schiff (2006), p. 421.

- ^ Schiff (2006).

- ^ Buckley, Martin. "Mysterious Wartime Death of French Novelist." Archived 23 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine BBC News, World Edition, 7 August 2004. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ^ Schiff (2006), pp. 430–433, 436–437.

- ^ Schiff (2006), p. 430.

- ^ Eyheramonno, Joelle. "Antoine de Saint-Exupéry." Slamaj personal website, 22 October 2011. Archived 11 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Schiff (2006), pp. 402–451.

- ^ Schiff (2006), pp. 434–438.

- ^ a b "Saint-Exupery Committed Suicide Says Diver Who Found Plane Wreckage." Archived 18 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine Cyber Diver News Network, 7 August 2004. (Note: old link location became a dead link)

- ^ Lichfield, John. "St Exupery plane wreck found in Med." The Independent, 28 May 2000.

- ^ a b "France Finds Crash Site of 'Little Prince' Author Saint-Exupery." Europe Intelligence Wire, Agence France-Presse, 7 April 2004. Retrieved 9 November 2011 via Gale General OneFile (subscription); Gale Document Number: GALE|A115071273.

- ^ a b Aero-relic.org. "Riou Island's F-5B Lightning, Rhône's Delta, France. Pilot: Commander Antoine de Saint-Exupéry (aircraft crash recovery report)". Archived 21 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine Aero-relic.org, 12 April 2004. Retrieved 10 August 2009.

- ^ "Saint-Exupéry's Plane Found". Toronto: The Globe and Mail, 8 April 2004, p. R6.

- ^ a b "Antoine de Saint-Exupéry aurait été abattu par un pilote allemand" (in French). Le Monde, 15 March 2008.

- ^ "Current Exhibitions: IWC-Saint Exupery Space." Archived 2 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine Association des Amis du Musée de l'Air website, 21 September 2011.

- ^ a b Rumbold, Richard & Stewart, Lady Margaret. The Winged Life Archived 16 April 2018 at the Wayback Machine, N.Y.: David McKay Company, 1953. P.214

- ^ Cicero magazine, 12 April 2008. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f Beale, Nick. "Saint-Exupéry Entre mythe et réalité." Aero Journal, No. 4, 2008, pp. 78–81. More details on the web-site "Ghost Bombers" (see External links)

- ^ "Saint-Exupéry episode." Archived 5 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine Ghostbombers.com. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

- ^ "Letter of Robert Heichele". Der Landser. No. 725. 1972.

- ^ Jackson, Michael (2013). The Other Shore: Essays on Writers and Writing. University of California Press. pp. 47–48.

- ISBN 978-0966070606.

- ^ UK National Archives file HW5/548, item CX/MSS/T263/29

- ^ "Detailansicht". Volksbund.de.

- ^ Tagliabue (2008).

- ^ "Wartime author mystery 'solved'". 17 March 2008. Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ Tagliabue, John. On the Trail of a Missing Aviator, Saint-Exupery The New York Times New York edition, 10 April 2008. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Julien, Guy. "Revisting Saint-Exupery." Aero Journal, No. 6, 2008.

- ^ "Ivan Rebroffs Bruder schoss Saint-Exupéry ab" (in German). Agence France-Presse, 15 March 2008. Archived 20 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ German "Pilot fears he killed writer St. Exupéry." Reuters news story quoting Rippert in Le Figaro, 16 March 2008. Retrieved 16 March 2008. Archived 19 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Altweg (2008).

- ^ Boenisch, Georg & Leick, Romain. Legenden | Gelassen in den Tod, Der Spiegel, 22 March 2008. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- ^ Bönisch & Leick (2008).

- ^ Bobek, Jan.Saint-Exupéry, lack of archival documents, HNED.cz, 29 March 2008. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- ^ Von Gartzen, Lino & Triebel, Claas. The Prince, The Pilot, and Antoine de Saint-Exupery, Herbig Verlag Publishing, 1 August 2008.

- ^ Ehrhardt, Patrick (1997). Les Chevaliers de l'Ombre : La 33eme Escadre de Reconnaissance : 1913–1993. Saverne.

- ^ "The True Events That Inspired 'The Little Prince'". Time. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- ^ "Wind, Sand and Stars Quotes by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry". www.goodreads.com. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- ^ "Brief Chronograph Of Publications." Archived 14 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine LePetitPrince.net, 26 October 2011. Note: the earliest year of publication is given for either of the French or English versions. All of Saint-Exupéry's literary works were originally created in French (he could neither speak nor write English very well), but some of his writings were translated and published in English prior to their French publication.

- ^ The French Review, American Association of Teachers of French, Vol. 19, No. 5, March 1946, p. 300 (subscription). Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- ^ "1939 Book Awards Given by Critics: Elgin Groseclose's 'Ararat' is Picked as Work Which Failed to Get Due Recognition", The New York Times, 14 February 1940, p. 25. via ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The New York Times (1851–2007).

- ^ a b Fay, Elliot G. "Saint-Exupéry in New York." Modern Language Notes, Johns Hopkins University Press, Vol. 61, No. 7, November 1946, p. 461.

- ^ Inman, William H. "Hotelier Saint-Exupery's Princely Instincts." Institutional Investor, March 2011. Retrieved online from General OneFile: 6 November 2011 (subscription).

- ^ Fay 1946, p. 463.

- ^ a b Smith, Maxwell A. Knight of the Air: The Life and Works of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry New York: Pageant Press, 1956; London: Cassell, 1959, bibliography, pp. 205–221.

- ^ Saint-Exupéry, Antoine de. A Sense of Life. New York: Funk & Wagnalls, 1965.

- Flying Magazine, January 1966, p. 114.

- ^ Saint-Exupéry (1965).

- ^ a b Saint-Exupéry, Antoine. Retrieved from Trussel.com: 26 May 2012:

- Saint-Exupéry, Antoine de. An Open Letter to Frenchmen Everywhere, The New York Times Magazine, 29 November 1942, p. 7. Also published in French as:

- Saint-Exupéry, Antoine de. "Voulez-vous, Français, vous reconcilier? (French People, Would You Reconcile?)." Le Canada, de Montréal, 30 November 1942.

- ^ "Articles of StEx: Brief Chronograph of Publications." Archived 15 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine lepetitprince.net, 2011. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ^ Schiff (1996), p. 414.

- ^ "French Code of Intellectual Property (in French)." Archived 29 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine celog.fr. Retrieved: 22 August 2012.

- ^ Schiff (2006), p. 438.

- ^ Basse, D.H. Le musée de l'Air du Bourget va ouvrir un espace Saint-Exupéry, French Recreational Aviation bulletin board website. Retrieved from Groups.Google.com 14 March 2013. (in French)

- Archive.org, 13 March 2013. (in French)

- ^ Mandel, Charles. "Museum Marks Pilot's Life And Dangerous Times." Edmonton Journal, Edmonton, Alberta, 17 January 1995, p. A.11.

- ^ "The Legend of Saint-Exupéry in Brazil." Archived 26 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine TheLittlePrince.com, 11 March 2011.

- ^ "Toulouse va célébrer Antoine de Saint-Exupéry." Toulouse7.com, 22 September 2011.

- ^ USU Opens International Saint-Exupery Center Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Lomonosov Moscow State University in Ulyanovsk website, 28 February 2012. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ^ Rothstein, Edward. 70 Years on, Magic Concocted in Exile: The Morgan Explores the Origins of 'The Little Prince', The New York Times website, 23 January 2014, published in print 24 January 2014, p. C25 (New York edition). Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ Gaffney, Adrienne. On View | Long Live "The Little Prince", The New York Times blog website, 23 January 2014. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ Maloney, Jennifer. 'The Little Prince' lands at the Morgan Library: A New Exhibit Explores the Author's Years Writing in New York Archived 27 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine, The Wall Street Journal website, 23 January 2014. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- The Morgan Library & Museumwebsite, January 2014. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ^ Runcie, Charlotte. The story of The Little Prince and the Big Apple, The Telegraph website, 24 January 2014. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ Krôller, Eva-Marie. "Expo '67: Canada's Camelot?"[permanent dead link] Canadian Literature, Spring–Summer 1997, Issue 152–153, pp. 36–51. [dead link]

- ^ "MPC/MPO/MPS Archive". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- ISBN 978-3-540-00238-3.

- National Public Radio. Archivedfrom the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 8 November 2023.

- ^ Hut, Piet. Asteroid Deflection: Project B612 Archived 2020-08-18 at the Wayback Machine, Piet Hut webpage at the Institute for Advanced Study website. Retrieved July 24, 2014.

- ^ Powell, Corey S. "Developing Early Warning Systems for Killer Asteroids" Archived 2019-10-26 at the Wayback Machine, Discover, August 14, 2013, pp. 60–61 (subscription required).

- Marin County, California: Pacific Sun, July 7, 2004, via HighBeam Research; also published online as Rusty Schweickart: Space Man Archived 2015-12-05 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b Images of International Stamps (Government- and Private-Issue) Honoring Saint-Exupéry. Trussel.com website. Retrieved 9 February 2012.

- ^ Images of the Israeli Stamp and Related Issues. Trussel.com website. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- ^ "Antoine de Saint Exupéry Airport, San Antonio Oeste, Argentina" Archived 12 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Airport-information. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ^ About Us: What's In A Name? Archived 22 December 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Terre des hommes Ontario. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- ^ "About TDFIF: Our History." Archived 26 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine Terre des Hommes International Federation. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- ^ Mun-Delsalle, Y-Jean. "Guardians of the Future." The Peak Magazine, March 2011, p. 63. Archived 2 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Mun-Delsalle, Y-Jean. "Pursuits: Guardians Of The Future (article synopsis)." The Peak (magazine), March 2011. Archived 26 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "AEFE – École française Antoine-de-Saint-Exupéry". Aefe.fr. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ "École française Saint-Exupery". Ecole-saintexupery.org. Archived from the original on 4 January 2019. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ Schiff (2006), p. 445.

- ^ "Google's Celebration of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry's 110th Birthday." Archived 11 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine Logo-Google.com website, 29 June 2010.

- ^ "51 Heroes of Aviation". Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- ^ "A Note Fit for a Little Prince – PMG". Pmgnotes.com. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ Saint-Exupéry (2003).

- ^ Grode, Eric. "Musical Couple Turn to Aviator and His Wife." The New York Times New York edition, 21 August 2011, p. AR6.

Sources

- Altweg, Jurg (28 March 2008). "Aus Erfahrung skeptisch: Französische Zweifel an Saint-Exuperys Abschuss durch Horst Rippert". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. No. 32/S44. Frankfurt.

- Berton, Pierre. ISBN 0-385-25662-0.

- Bönisch, Georg; Leick, Romain (21 March 2008). "Gelassen in den Tod". Der Spiegel (in German).

- Brown, Hannibal (2004). "The Country Where the Stones Fly: Visions of a Little Prince". Archived from the original on 9 November 2006.[unreliable source?]

- Cate, Curtis (1970). Antoine de Saint-Exupéry : his life and times. Toronto: Longmans Canada Limited. ISBN 978-1557782915.

- ISBN 978-0-8103-0053-8.

- Cotsalas, Valerie (10 September 2000). "'The Little Prince': Born in Asharoken". The New York Times.

- Dunning, Jennifer (12 May 1989). "In the Footsteps of Saint-Exupery". The New York Times.

- Murland, Hugh (1991). "The Spirit of Saint-Exupery". ISSN 0143-5450.

- Saint-Exupéry, Antoine de (1943). The Little Prince (1st ed.). San Diego.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Saint-Exupéry, Antoine de (1965) [1956]. A Sense of Life. Translated by Adrienne W. Foulke. Funk & Wagnalls.

- Saint-Exupéry, Consuelo (2003). The Tale of the Rose: The Love Story Behind The Little Prince. Translated by ISBN 978-0-8129-6717-3.

- ISBN 978-0-3068-0740-4.

- ISBN 978-0-8050-7913-5.

- Severson, Marilyn S. (2004). Masterpieces of French literature. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-31484-1.

- La Gazette des Français du Paraguay Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, Vol de nuit 1931, Vaincre l'impossible – Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, Vuelo nocturno 1931, Superar lo desconocido bilingue, numéro 14 année II, Assomption, Paraguay.

- Webster, Paul (1994). Antoine de Saint-Exupéry : the life and death of The Little Prince. London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0333617021.

Further reading

Selected biographies

- Chevrier, Pierre (pseudonym of Hélène (Nelly) de Vogüé). Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. Montreal, Quebec, Canada: La librairie Gallimard de Montréal, 1950.

- Migeo, Marcel. Saint-Exupéry. New York: McGraw-Hill, (trans. 1961), 1960.

- Peyre, Henri. French Novelists of Today. New York: Oxford UP, 1967.

- Robinson, Joy D. Marie. Antoine de Saint-Exupéry (Twayne's World Authors series: French literature). Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1984, pp. 120–142.

- Rumbold, Richard and Lady Margaret Stewart. The Winged Life: A Portrait of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, Poet and Airman. New York: D. McKay, 1955.

- Smith, Maxwell A. Knight of the Air: The Life and Works of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. New York: Pageant Press, 1956.

External links

- Works by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry at Faded Page (Canada)

- Antoine de Saint-Exupéry (society) (official website) (in French)

- Antoine de Saint-Exupéry Youth Foundation (F-ASEJ) (official website) (in French)

- 2011 Année Antoine de Saint-Exupéry Toulouse celebration of Saint-Exupéry in 2011 (in French)

- Major bibliography of French and English biographical works on Saint-Exupéry

- A website dedicated to the Centennial Anniversary of Antoine and Consuelo de Saint-Exupéry

- The Luftwaffe and Saint-Exupéry: the evidence (in the website "Ghost Bombers")