Apomorphine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Apokyn, Kynmobi |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a604020 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

Subcutaneous injection (SQ), sublingual | |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

phase II | |

| Onset of action | 10–20 min |

| Elimination half-life | 40 minutes |

| Duration of action | 60–90 min |

| Excretion | Liver |

| Identifiers | |

| |

JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| Data page | |

| Apomorphine (data page) | |

| | |

Apomorphine, sold under the brand name Apokyn among others, is a type of

Historically, apomorphine has been tried for a variety of uses, including as a way to relieve anxiety and craving in alcoholics, an emetic (to induce vomiting), for treating stereotypies (repeated behaviour) in farmyard animals, and more recently in treating

Apomorphine was also used as a private treatment of

Medical uses

Apomorphine is used in advanced

Contraindications

The main and

Side effects

Nausea and vomiting are common side effects when first beginning therapy with apomorphine;[10] antiemetics such as trimethobenzamide or domperidone, dopamine antagonists,[11] are often used while first starting apomorphine. Around 50% of people grow tolerant enough to apomorphine's emetic effects that they can discontinue the antiemetic.[5][6]

Other side effects include orthostatic hypotension and resultant fainting,

Pharmacology

Mechanism of action

Apomorphine's

Apomorphine improves motor function by activating dopamine receptors in the

Apomorphine also decreases the breakdown of dopamine in the brain (though it inhibits its synthesis as well).

Apomorphine causes vomiting by acting on dopamine receptors in the

Pharmacokinetics

While apomorphine has lower

Apomorphine possesses

| Receptor | Ki (nM) | Action |

|---|---|---|

D1 |

484 | (partial) agonista |

D2 |

52 | partial agonist (IA = 79% at D2S; 53% at D2L) |

D3

|

26 | partial agonist (IA = 82%) |

D4

|

4.37 | partial agonist (IA = 45%) |

D5

|

188.9 | (partial) agonista |

| aThough its efficacies at D1 and D5 are unclear, it is known to act as an agonist at these sites.[29] | ||

| Receptor | Ki (nM) | Action |

|---|---|---|

| 5-HT1A | 2,523 | partial agonist |

| 5-HT1B | 2,951 | no action |

| 5-HT1D | 1,230 | no action |

| 5-HT2A | 120 | antagonist |

| 5-HT2B | 132 | antagonist |

| 5-HT2C | 102 | antagonist |

| Receptor | Ki (nM) | Action |

|---|---|---|

| α1A-adrenergic | 1,995 | antagonist |

| α1B-adrenergic | 676 | antagonist |

| α1D-adrenergic | 64.6 | antagonist |

| α2A-adrenergic | 141 | antagonist |

| α2B-adrenergic | 66.1 | antagonist |

| α2C-adrenergic | 36.3 | antagonist |

It has a Ki of over 10,000 nM (and thus negligible affinity) for

Apomorphine has a high

Toxicity depends on the route of administration; the

Chemistry

Properties

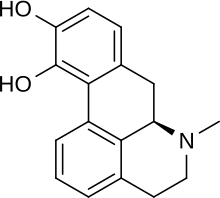

Apomorphine has a catechol structure similar to that of dopamine.[20]

Synthesis

Several techniques exist for the creation of apomorphine from morphine. In the past, morphine had been combined with hydrochloric acid at high temperatures (around 150 °C) to achieve a low yield of apomorphine, ranging anywhere from 0.6% to 46%.[31]

More recent techniques create the apomorphine in a similar fashion, by heating it in the presence of any acid that will promote the essential dehydration rearrangement of morphine-type

History

The pharmacological effects of the naturally-occurring analog

with the plant featuring in tomb frescoes and associated with entheogenic rites. It is also observed in Egyptian erotic cartoons, suggesting that they were aware of its erectogenic properties.The modern medical history of apomorphine begins with its synthesis by Arppe in 1845[35] from morphine and sulfuric acid, although it was named sulphomorphide at first. Matthiesen and Wright (1869) used hydrochloric acid instead of sulfuric acid in the process, naming the resulting compound apomorphine. Initial interest in the compound was as an emetic, tested and confirmed safe by London doctor Samuel Gee,[36] and for the treatment of stereotypies in farmyard animals.[37] Key to the use of apomorphine as a behavioural modifier was the research of Erich Harnack, whose experiments in rabbits (which do not vomit) demonstrated that apomorphine had powerful effects on the activity of rabbits, inducing licking, gnawing and in very high doses convulsions and death.

Treatment of alcoholism

Apomorphine was one of the earliest used pharmacotherapies for

In four minutes free emesis followed, rigidity gave way to relaxation, excitement to somnolence, and without further medication the patient, who before had been wild and delirious, went off into a quiet sleep.

Douglas saw two purposes for apomorphine:

[it can be used to treat] a paroxysm of dipsomania [an episode of intense alcoholic craving]... in minute doses it is much more rapidly efficient in stilling the dipsomaniac craving than strychnine or atropine… Four or even 3m [minim – roughly 60 microlitres] of the solution usually checks for some hours the incessant demands of the patient… when he awakes from the apomorphine sleep he may still be demanding alcohol, though he is never then so insistent as before. Accordingly it may be necessary to repeat the dose, and even to continue to give it twice or three times a day. Such repeated doses, however, do not require to be so large: 4 or even 3m is usually sufficient.

This use of small, continuous doses (1/30th of a grain, or 2.16 mg by Douglas) of apomorphine to reduce alcoholic craving comes some time before Pavlov's discovery and publication of the idea of the "conditioned reflex" in 1903. This method was not limited to Douglas; the Irish doctor Francis Hare, who worked in a sanatorium outside London from 1905 onward, also used low-dose apomorphine as a treatment, describing it as "the most useful single drug in the therapeutics of inebriety".[41] He wrote:

In (the) sanatorium it is used in three different sets of circumstances: (1) in maniacal or hysterical drunkenness: (2) during the paroxysm of dipsomania, in order to still the craving for alcohol; and (3) in essential insomnia of a special variety... [after giving apomorphine] the patient's mental condition is entirely altered. He may be sober: he is free from the time being from any craving from alcohol. The craving may return, however, and then it is necessary to repeat the injection, it may be several times at intervals of a few hours. These succeeding injections should be quite small, 3 to 6 min. being sufficient. Doses of this size are rarely emetic. There is little facial pallor, a sensation as of the commencement of sea-sickness, perhaps a slight malaise with a sudden subsidence of the craving for alcohol, followed by a light and short doze.

He also noted there appeared to be a significant prejudice against the use of apomorphine, both from the associations of its name and doctors being reluctant to give hypodermic injections to alcoholics. In the US, the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act

In the 1950s the neurotransmitter dopamine was discovered in the brain by Katharine Montagu, and characterised as a neurotransmitter a year later by Arvid Carlsson, for which he would be awarded the Nobel Prize.[42] A. N. Ernst then discovered in 1965 that apomorphine was a powerful stimulant of dopamine receptors.[43] This, along with the use of sublingual apomorphine tablets, led to a renewed interest in the use of apomorphine as a treatment for alcoholism. A series of studies of non-emetic apomorphine in the treatment of alcoholism were published, with mostly positive results.[44][45][46][47][48] However, there was little clinical consequence.

Parkinson's disease

The use of apomorphine to treat "the shakes" was first suggested by Weil in France in 1884,[49] although seemingly not pursued until 1951.[50] Its clinical use was first reported in 1970 by Cotzias et al.,[51] although its emetic properties and short half-life made oral use impractical. A later study found that combining the drug with the antiemetic domperidone improved results significantly.[52] The commercialization of apomorphine for Parkinson's disease followed its successful use in patients with refractory motor fluctuations using intermittent rescue injections and continuous infusions.[53]

Aversion therapy

Aversion therapy in alcoholism had its roots in Russia in the early 1930s,[54] with early papers by Pavlov, Galant and Sluchevsky and Friken,[55] and would remain a strain in the Soviet treatment of alcoholism well into the 1980s. In the US a particularly notable devotee was Dr Voegtlin,[56] who attempted aversion therapy using apomorphine in the mid to late 1930s. However, he found apomorphine less able to induce negative feelings in his subjects than the stronger and more unpleasant emetic emetine.

In the UK, however, the publication of J Y Dent's (who later went on to treat Burroughs) 1934 paper "Apomorphine in the treatment of Anxiety States"[57] laid out the main method by which apomorphine would be used to treat alcoholism in Britain. His method in that paper is clearly influenced by the then-novel idea of aversion:

He is given his favourite drink, and his favourite brand of that drink... He takes it stronger than is usual to him... The small dose of apomorphine, one-twentieth of a grain [3.24mg], is now given subcutaneously into his thigh, and he is told that he will be sick in a quarter of an hour. A glass of whisky and water and a bottle of whisky are left by his bedside. At six o'clock (four hours later) he is again visited and the same treatment is again administered... The nurse is told in confidence that if he does not drink, one-fortieth [1.62 mg] of a grain of apomorphine should be injected during the night at nine o'clock, one o'clock, and five o'clock, but that if he drinks the injection should be given soon after the drink and may be increased to two hourly intervals. In the morning at about ten he is again given one or two glasses of whisky and water... and again one-twentieth of a grain [3.24 mg] of apomorphine is injected... The next day he is allowed to eat what he likes, he may drink as much tea as he likes... He will be strong enough to get up and two days later he leaves the home.

However, even in 1934 he was suspicious of the idea that the treatment was pure conditioned reflex – "though vomiting is one of the ways that apomorphine relives the patient, I do not believe it to be its main therapeutic effect." – and by 1948 he wrote:[3]

It is now twenty-five years since I began treating cases of anxiety and alcoholism with apomorphine, and I read my first paper before this Society fourteen years ago. Up till then I had thought, and, unfortunately, I said in my paper, that the virtue of the treatment lay in the conditioned reflex of aversion produced in the patient. This statement is not even a half truth… I have been forced to the conclusion that apomorphine has some further action than the production of a vomit.

This led to his development of lower-dose and non-aversive methods, which would inspire a positive trial of his method in Switzerland by Dr Harry Feldmann[58] and later scientific testing in the 1970s, some time after his death. However, the use of apomorphine in aversion therapy had escaped alcoholism, with its use to treat homosexuality leading to the death of a British Army Captain Billy Clegg Hill in 1962,[59] helping to cement its reputation as a dangerous drug used primarily in archaic behavioural therapies.

Opioid addiction

In his Deposition: Testimony Concerning a Sickness in the introduction to later editions of Naked Lunch (first published in 1959), William S. Burroughs wrote that apomorphine treatment was the only effective cure to opioid addiction he has encountered:

The apomorphine cure is qualitatively different from other methods of cure. I have tried them all. Short reduction, slow reduction,

tranquilizers, sleeping cures, tolserol, reserpine. None of these cures lasted beyond the first opportunity to relapse. I can say that I was never metabolically cured until I took the apomorphine cure... The doctor, John Yerbury Dent, explained to me that apomorphine acts on the back brain to regulate the metabolism and normalize the blood stream in such a way that the enzyme stream of addiction is destroyed over a period of four to five days. Once the back brain is regulated apomorphine can be discontinued and only used in case of relapse.

He goes on to lament the fact that as of his writing, little to no research has been done on apomorphine or variations of the drug to study its effects on curing addiction, and perhaps the possibility of retaining the positive effects while removing the side effect of vomiting.

Despite his claims throughout his life, Burroughs never really cured his addiction and was back to using opiates within years of his apomorphine "cure".[60] However, he insisted on apomorphine's effectiveness in several works and interviews.[citation needed]

Society and culture

- Apomorphine has a vital part in Agatha Christie's detective story Sad Cypress.

- The 1965 Tuli Kupferberg song "Hallucination Horrors" recommends apomorphine at the end of each verse as a cure for hallucinations brought on by a humorous variety of intoxicants; the song was recorded by The Fugs and appears on the album Virgin Fugs.

Research

There is renewed interest in the use of apomorphine to treat addiction, in both smoking cessation[61] and alcoholism.[62] As the drug is known to be reasonably safe for use in humans, it is a viable target for repurposing.

Apomorphine has been researched as a possible treatment for erectile dysfunction and female hypoactive sexual desire disorder, though its efficacy has been limited.

Alzheimer's disease

Apomorphine is reported to be an inhibitor of amyloid beta protein fiber formation, whose presence is a hallmark of Alzheimer's disease, and a potential therapeutic under the amyloid hypothesis.[65]

Alternative administration routes

Two routes of administration are currently clinically utilized: subcutaneous (either as intermittent injections or continuous infusion) and sublingual. Other non-invasive administration routes were investigated as a substitute for parenteral administration, reaching different preclinical and clinical stages. These include: peroral,[66] nasal,[67][68][69][70] pulmonary,[71] transdermal,[72] rectal,[73][74] and buccal,[75][76] as well as iontophoresis methods.[77]

Veterinary use

Apomorphine is used to inducing vomiting in

One of the reasons apomorphine is a preferred drug is its reversibility:

Apomorphine does not work in

References

- ^ S2CID 6200455.

- S2CID 32386793.

- ^ .

- ^ "Apomorphine Uses, Side Effects & Warnings". Drugs.com. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-323-37697-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Apomorphine Hydrochloride Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- ^ PMID 9522772.

- S2CID 231945531.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7506-5428-9.

- S2CID 19617827.

- ^ PMID 11128615.

- ^ "Apomorphine". Medline Plus. US National Library of Medicine. 15 June 2017. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4051-7872-3.

- PMID 21873960.

- PMID 18083605.

- ^ a b c d e f g U.S. National Library of Medicine. "Apomorphine". PubChem. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- ISBN 978-1-85317-379-0.

- PMID 18274665.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-203-33776-9.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4684-8514-1.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-08-058106-4.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link - PMID 10872797.

- S2CID 38444849.

- S2CID 20317993.

- ISBN 978-0-8138-2061-3.

- ^ Roth BL, Driscol J (12 January 2011). "PDSP Ki Database". Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the United States National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved 1 July 2014. Note: Values for humans are used. If there is more than one value listed for humans, their average is used.

- S2CID 35238120.

- S2CID 19260572.

- S2CID 7485959.

- ISBN 978-0471476627.

- ^ a b Gurusamy N. "Process for making apomorphine and apocodeine".

- ISBN 978-1483152233.

- PMID 28266899.

- PMID 14749409.

- PMID 23549143.

- ^ Gee S (1869). "On the action of a new organic base, apomorphia". Transactions of the Clinical Society of London. 2: 166–169.

- ^ Feser J (1873). "Die in neuester Zeit in Anwendung gekommen Arzneimittel: 1. Apomorphinum hydrochloratum" [The most recently used medicines: 1. Apomorphine hydrochloride]. Z Prakt Veterinairwiss: 302–306.

- ^ Tompkins J (1899). "Apomorphine in Acute Alcoholic Delirium". Medical Record.

- .

- ^ Douglas CJ (1899). "The withdrawal of alcohol in delirium tremens". The New York Medical Journal: 626.

- ^ Hare F (1912). On alcoholism; its clinical aspects and treatment. London: Churchill.

- PMID 11165672.

- S2CID 7445311.

- PMID 14328866.

- PMID 326687.

- PMID 352969.

- PMID 341937.

- PMID 5033142.

- ^ Weil E (1884). "De l'apomorphine dans certain troubles nerveux" [On apomorphine in certain nervous shakes]. Lyon Med (in French). 48: 411–419.

- PMID 14913646.

- PMID 4901383.

- S2CID 43526111.

- S2CID 35208453.

- OCLC 191318001.

- )

- PMID 15424345.

- ISSN 1360-0443.

- PMID 13075975.

- ^ "Gay injustice 'was widespread'". 12 September 2009. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ Birmingham J (2 November 2009). "William Burroughs and the History of Heroin". RealityStudio.

- PMID 26690764.

- ^ "Apomorphine – A forgotten treatment for alcoholism". apomorphine.info. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ISBN 978-3-319-52539-6.

- ^ "Abbott Withdraws Application for an Impotence Pill". Bloomberg News via The New York Times. 1 July 2000.

- PMID 12167652.

- PMID 27615708.

- PMID 27615996.

- PMID 2283516.

- S2CID 7126130.

- PMID 10915935.

- S2CID 22189634.

- S2CID 28397399.

- PMID 1527553.

- S2CID 30947265.

- S2CID 229317834.

- S2CID 219331493.

- PMID 15588905.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-323-44402-6.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4557-4325-4.

- ISBN 978-0-470-95964-0.

- ISBN 978-0-7216-0639-2.