Aries (constellation)

| Constellation | |

| |

| Abbreviation | Ari[1] |

|---|---|

| Genitive | Arietis |

| Pronunciation | /ˈɛəriːz/, genitive 39th) |

| Main stars | 4, 9 |

| Bayer/Flamsteed stars | 61 |

| Stars with planets | 6 |

| Stars brighter than 3.00m | 2 |

| Stars within 10.00 pc (32.62 ly) | 2[a] |

| Brightest star | Hamal (α Ari) (2.01m) |

| Messier objects | 0 |

| Meteor showers |

|

| Bordering constellations | |

| Visible at latitudes between +90° and −60°. Best visible at 21:00 (9 p.m.) during the month of December. | |

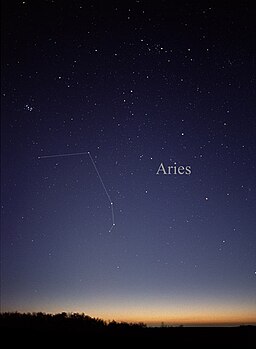

Aries is one of the constellations of the zodiac. It is located in the Northern celestial hemisphere between Pisces to the west and Taurus to the east. The name Aries is Latin for ram. Its old astronomical symbol is ![]() (♈︎). It is one of the 48 constellations described by the 2nd century astronomer Ptolemy, and remains one of the 88 modern constellations. It is a mid-sized constellation ranking 39th in overall size, with an area of 441 square degrees (1.1% of the celestial sphere).

(♈︎). It is one of the 48 constellations described by the 2nd century astronomer Ptolemy, and remains one of the 88 modern constellations. It is a mid-sized constellation ranking 39th in overall size, with an area of 441 square degrees (1.1% of the celestial sphere).

Aries has represented a ram since late Babylonian times. Before that, the stars of Aries formed a farmhand. Different cultures have incorporated the stars of Aries into different constellations including twin inspectors in China and a porpoise in the Marshall Islands. Aries is a relatively dim constellation, possessing only four bright stars:

History and mythology

Aries is now recognized as an official constellation, albeit as a specific region of the sky, by the

In ancient Egyptian astronomy, Aries was associated with the god

Aries was not fully accepted as a constellation until classical times.

Historically, Aries has been depicted as a crouched, wingless ram with its head turned towards Taurus.

The

The

In 1922, the International Astronomical Union defined its recommended three-letter abbreviation, "Ari".

In non-Western astronomy

In traditional

In a similar system to the Chinese, the first lunar mansion in

Features

Stars

Bright stars

Aries has three prominent stars forming an

The constellation is home to several double stars, including Epsilon, Lambda, and Pi Arietis. ε Arietis is a binary star with two white components. The primary is of magnitude 5.2 and the secondary is of magnitude 5.5. The system is 290 light-years from Earth.[12] Its overall magnitude is 4.63, and the primary has an absolute magnitude of 1.4. Its spectral class is A2. The two components are separated by 1.5 arcseconds.[29] λ Arietis is a wide double star with a white-hued primary and a yellow-hued secondary. The primary is of magnitude 4.8 and the secondary is of magnitude 7.3.[12] The primary is 129 light-years from Earth.[35] It has an absolute magnitude of 1.7 and a spectral class of F0.[29] The two components are separated by 36 arcseconds at an angle of 50°; the two stars are located 0.5° east of 7 Arietis.[3] π Arietis is a close binary star with a blue-white primary and a white secondary. The primary is of magnitude 5.3 and the secondary is of magnitude 8.5.[12] The primary is 776 light-years from Earth.[36] The primary itself is a wide double star with a separation of 25.2 arcseconds; the tertiary has a magnitude of 10.8. The primary and secondary are separated by 3.2 arcseconds.[29]

Most of the other stars in Aries visible to the naked eye have magnitudes between 3 and 5.

Variable stars

Aries has its share of variable stars, including R and U Arietis, Mira-type variable stars, and T Arietis, a semi-regular variable star.

Deep sky objects

NGC 821 is an E6 elliptical galaxy. It is unusual because it has hints of an early spiral structure, which is normally only found in

Meteor showers

Aries is home to several

The

The Autumn Arietids also radiate from Aries. The shower lasts from 7 September to 27 October and peaks on 9 October. Its peak rate is low.[57] The Epsilon Arietids appear from 12 to 23 October.[8] Other meteor showers radiating from Aries include the October Delta Arietids, Daytime Epsilon Arietids, Daytime May Arietids, Sigma Arietids, Nu Arietids, and Beta Arietids.[54] The Sigma Arietids, a class IV meteor shower, are visible from 12 to 19 October, with a maximum zenithal hourly rate of less than two meteors per hour on 19 October.[58]

Planetary systems

Aries contains several stars with

See also

- Aries (Chinese astronomy)

References

Explanatory notes

- Teegarden's star and TZ Arietis. The distance can be calculated from their parallax, listed in SIMBAD, by taking the inverse of the parallax and multiplying by 3.26.

Citations

- ^ a b Russell 1922, p. 469.

- ^ a b "Aries, constellation boundary". The Constellations. International Astronomical Union. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g Thompson & Thompson 2007, pp. 90–91.

- ^ a b RECONS, The 100 Nearest Star Systems.

- ^ Pasachoff 2000, pp. 128–189.

- ^ Evans 1998, p. 6.

- ^ Rogers, Mesopotamian Traditions 1998.

- ^ a b c d e f g Staal 1988, pp. 36–41.

- ^ Olcott 2004, p. 56.

- ^ Rogers, Mediterranean Traditions 1998.

- ^ a b Pasachoff 2000, pp. 84–85.

- ^ a b c d e f Ridpath 2001, pp. 84–85.

- ^ a b c d e f Moore & Tirion 1997, pp. 128–129.

- ^ a b c d e f Ridpath, Star Tales Aries: The Ram.

- ^ Evans 1998, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Winterburn 2008, p. 5.

- ^ a b c d Olcott 2004, pp. 57–58.

- ^ a b c d Winterburn 2008, pp. 230–231.

- ^ Savage-Smith & Belloli 1985, p. 80.

- ^ Savage-Smith & Belloli 1985, p. 123.

- ^ Savage-Smith & Belloli 1985, pp. 162–164.

- ^ a b Ridpath, Star Tales Musca Borealis.

- ^ IAU, The Constellations, Aries.

- ^ Staal 1988, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Makemson 1941, p. 279.

- ^ Ridpath, Popular Names of Stars.

- ^ a b "Naming Stars". IAU.org. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- ^ SIMBAD Alpha Arietis.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Moore 2000, pp. 337–338.

- ^ a b Savage-Smith & Belloli 1985, p. 121.

- ^ SIMBAD Beta Arietis.

- ^ a b c d e f Burnham 1978, pp. 245–252.

- ^ Davis 1944.

- ^ SIMBAD Gamma Arietis.

- ^ SIMBAD Lambda Arietis.

- ^ SIMBAD Pi Arietis.

- ^ SIMBAD Delta Arietis.

- ^ SIMBAD Zeta Arietis.

- ^ SIMBAD 14 Arietis.

- ^ SIMBAD 39 Arietis.

- ^ SIMBAD 35 Arietis.

- ^ SIMBAD 41 Arietis.

- ^ SIMBAD 53 Arietis.

- ^ SIMBAD R Arietis.

- ^ SIMBAD T Arietis.

- ^ Good 2003, pp. 136–137.

- ^ a b c d e Bratton 2011, pp. 63–66.

- ^ SIMBAD Arp 276.

- ^ Belokurov et al. 2009.

- ^ Jopek, "Daytime Arietids".

- ^ Bakich 1995, p. 60.

- ^ NASA, "June's Invisible Meteors".

- ^ a b Jenniskens 2006, pp. 427–428.

- ^ a b Jopek, "Meteor List".

- ^ Levy 2007, p. 122.

- ^ Langbroek 2003.

- ^ Levy 2007, p. 119.

- ^ Lunsford, Showers.

- ^ Wright et al. 2009.

- ^ ExoPlanet HD 12661.

- ^ ExoPlanet HD 20367.

- ^ S2CID 189999121.

- S2CID 50864060.

Bibliography

- Bakich, Michael E. (1995). The Cambridge Guide to the Constellations. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-44921-2.

- Belokurov, V.; Walker, M. G.; Evans, N. W.; Gilmore, G.; Irwin, M. J.; Mateo, M.; Mayer, L.; Olszewski, E.; Bechtold, J.; Pickering, T. (August 2009). "The discovery of Segue 2: a prototype of the population of satellites of satellites". S2CID 20051174.

- Bratton, Mark (2011). The Complete Guide to the Herschel Objects: Sir William Herschel's Star Clusters, Nebulae, and Galaxies. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-76892-4.

- Burnham, Robert Jr. (1978). Burnham's Celestial Handbook (2nd ed.). Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-24063-3.

- Davis, George A. Jr. (1944). "The Pronunciations, Derivations, and Meanings of a Selected List of Star Names". Popular Science. 52: 8. Bibcode:1944PA.....52....8D.

- Evans, James (1998). The History and Practice of Ancient Astronomy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-509539-5.

- Good, Gerry A. (2003). Observing Variable Stars. Springer. ISBN 978-1-85233-498-7.

- Jenniskens, Peter (2006). Meteor Showers and Their Parent Comets. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85349-1.

- Langbroek, Marco (20 August 2003). "The November–December delta-Arietids and asteroid 1990 HA: On the trail of meteoroid stream with meteorite-sized members". WGN, Journal of the International Meteor Organization. 31 (6): 177–182. Bibcode:2003JIMO...31..177L.

- Levy, David H. (2007). David Levy's Guide to Observing Meteor Showers. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-69691-3.

- Makemson, Maud Worcester (1941). The Morning Star Rises: an account of Polynesian astronomy. Yale University Press. Bibcode:1941msra.book.....M.

- Moore, Patrick; Tirion, Wil (1997). Cambridge Guide to Stars and Planets (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-58582-8.

- Moore, Patrick (2000). The Data Book of Astronomy. Institute of Physics Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7503-0620-1.

- Olcott, William Tyler (2004). Star Lore: Myths, Legends, and Facts. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-43581-7.

- Pasachoff, Jay M. (2000). A Field Guide to the Stars and Planets (4th ed.). Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-93431-9.

- Ridpath, Ian (2001). Stars and Planets Guide. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-08913-3.

- Rogers, John H. (1998). "Origins of the Ancient Constellations: I. The Mesopotamian Traditions". Journal of the British Astronomical Association. 108 (1): 9–28. Bibcode:1998JBAA..108....9R.

- Rogers, John H. (1998). "Origins of the Ancient Constellations: II. The Mediterranean Traditions". Journal of the British Astronomical Association. 108 (2): 79–89. Bibcode:1998JBAA..108...79R.

- Russell, Henry Norris (October 1922). "The New International Symbols for the Constellations". Bibcode:1922PA.....30..469R.

- S2CID 129450664.

- Staal, Julius D. W. (1988). The New Patterns in the Sky: Myths and Legends of the Stars. The McDonald and Woodward Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-939923-04-5.

- Thompson, Robert Bruce; Thompson, Barbara Fritchman (2007). Illustrated Guide to Astronomical Wonders. O'Reilly Media. ISBN 978-0-596-52685-6.

- Winterburn, Emily (2008). The Stargazer's Guide: How to Read Our Night Sky. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-06-178969-4.

- Wright, J. T.; Fischer, D. A.; Ford, Eric B.; Veras, D.; Wang, J.; Henry, G. W.; Marcy, G. W.; Howard, A. W.; Johnson, John Asher (2009). "A Third Giant Planet Orbiting HIP 14810". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 699 (2): L97–L101. S2CID 8075527.

Online sources

- "Aries Constellation Boundary". The Constellations. International Astronomical Union. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- "Notes for star HD 12661". Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia. Archived from the original on 5 May 2012. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- "Notes for star HD 20367". Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia. Archived from the original on 6 November 2007. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- Jopek, T. J. (3 March 2012). "Daytime Arietids". Meteor Data Center. International Astronomical Union. Archived from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- Jopek, T. J. (3 March 2012). "List of All Meteor Showers". Meteor Data Center. International Astronomical Union. Archived from the original on 12 August 2012. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- Lunsford, Robert (16 January 2012). "2012 Meteor Shower List". American Meteor Society. Retrieved 20 June 2012.

- "June's Invisible Meteors". NASA. 6 June 2000. Archived from the original on 17 August 2020. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- "The 100 Nearest Star Systems". Research Consortium on Nearby Stars. 1 January 2012. Archived from the original on 13 May 2012. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- Ridpath, Ian. "Popular Names of Stars". Retrieved 26 May 2012.

- Ridpath, Ian (1988). "Aries: The Ram". Star Tales. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- Ridpath, Ian (1988). "Musca Borealis". Star Tales. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- "Alpha Arietis". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- "Beta Arietis". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- "Gamma Arietis". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- "Lambda Arietis". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- "Pi Arietis". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- "Delta Arietis". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- "Zeta Arietis". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- "14 Arietis". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- "39 Arietis". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- "35 Arietis". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- "41 Arietis". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- "53 Arietis". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- "R Arietis". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- "T Arietis". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- "Arp 276". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

External links

- The Deep Photographic Guide to the Constellations: Aries

- The clickable Aries

- Star Tales – Aries

- Warburg Institute Iconographic Database (medieval and early modern images of Aries)