Arsenic

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Arsenic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Allotropes | grey (most common), yellow, black (see Allotropes of arsenic) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | metallic grey | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar°(As) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Arsenic in the periodic table | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 34.76 kJ/mol (?) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | 24.64 J/(mol·K) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapor pressure

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Arabic alchemists (before AD 815) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Isotopes of arsenic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Arsenic is a

The primary use of arsenic is in alloys of

A few species of bacteria are able to use arsenic compounds as respiratory metabolites. Trace quantities of arsenic are an essential dietary element in rats, hamsters, goats, chickens, and presumably other species. A role in human metabolism is not known.[12][13] However, arsenic poisoning occurs in multicellular life if quantities are larger than needed. Arsenic contamination of groundwater is a problem that affects millions of people across the world.

The

Characteristics

Physical characteristics

The three most common arsenic

Isotopes

Arsenic occurs in nature as one stable

At least 10 nuclear isomers have been described, ranging in atomic mass from 66 to 84. The most stable of arsenic's isomers is 68mAs with a half-life of 111 seconds.[23]

Chemistry

Arsenic has a similar electronegativity and ionization energies to its lighter congener phosphorus and accordingly readily forms covalent molecules with most of the nonmetals. Though stable in dry air, arsenic forms a golden-bronze tarnish upon exposure to humidity which eventually becomes a black surface layer.

Compounds

Compounds of arsenic resemble in some respects those of

Inorganic compounds

One of the simplest arsenic compounds is the trihydride, the highly toxic, flammable,

Arsenic forms colorless, odorless, crystalline

The protonation steps between the arsenate and arsenic acid are similar to those between phosphate and phosphoric acid. Unlike phosphorous acid, arsenous acid is genuinely tribasic, with the formula As(OH)3.[29]

A broad variety of sulfur compounds of arsenic are known. Orpiment (

All trihalides of arsenic(III) are well known except the astatide, which is unknown. Arsenic pentafluoride (AsF5) is the only important pentahalide, reflecting the lower stability of the +5 oxidation state; even so, it is a very strong fluorinating and oxidizing agent. (The pentachloride is stable only below −50 °C, at which temperature it decomposes to the trichloride, releasing chlorine gas.[18])

Alloys

Arsenic is used as the group 5 element in the

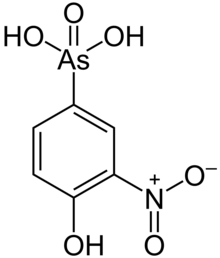

Organoarsenic compounds

A large variety of organoarsenic compounds are known. Several were developed as chemical warfare agents during World War I, including vesicants such as lewisite and vomiting agents such as adamsite.[37][38][39] Cacodylic acid, which is of historic and practical interest, arises from the methylation of arsenic trioxide, a reaction that has no analogy in phosphorus chemistry. Cacodyl was the first organometallic compound known (even though arsenic is not a true metal) and was named from the Greek κακωδία "stink" for its offensive odor; it is very poisonous.[40]

Occurrence and production

Arsenic is the 53rd most abundant element in the

In 2014, China was the top producer of white arsenic with almost 70% world share, followed by Morocco, Russia, and Belgium, according to the British Geological Survey and the United States Geological Survey.[44] Most arsenic refinement operations in the US and Europe have closed over environmental concerns. Arsenic is found in the smelter dust from copper, gold, and lead smelters, and is recovered primarily from copper refinement dust.[45]

On roasting arsenopyrite in air, arsenic sublimes as arsenic(III) oxide leaving iron oxides,[42] while roasting without air results in the production of gray arsenic. Further purification from sulfur and other chalcogens is achieved by sublimation in vacuum, in a hydrogen atmosphere, or by distillation from molten lead-arsenic mixture.[46]

| Rank | Country | 2014 As2O3 Production[44] |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 25,000 T | |

| 2 | 8,800 T | |

| 3 | 1,500 T | |

| 4 | 1,000 T | |

| 5 | 52 T | |

| 6 | 45 T | |

| — | World Total (rounded) | 36,400 T |

History

The word arsenic has its origin in the Syriac word ܙܪܢܝܟܐ zarnika,[47][48] from Arabic al-zarnīḵ الزرنيخ 'the orpiment', based on Persian zar ("gold") from the word زرنيخ zarnikh, meaning "yellow" (literally "gold-colored") and hence "(yellow) orpiment". It was adopted into Greek (using folk etymology) as arsenikon (ἀρσενικόν) – a neuter form of the Greek adjective arsenikos (ἀρσενικός), meaning "male", "virile".

Latin-speakers adopted the Greek term as arsenicum, which in French ultimately became arsenic, whence the English word "arsenic".[48] Arsenic sulfides (orpiment,

During the Bronze Age, arsenic was often included in the manufacture of bronze, making the alloy harder (so-called "arsenical bronze").[54][55] Jabir ibn Hayyan described the isolation of arsenic before 815 AD.[56] Albertus Magnus (Albert the Great, 1193–1280) later isolated the element from a compound in 1250, by heating soap together with arsenic trisulfide.[57] In 1649, Johann Schröder published two ways of preparing arsenic.[58] Crystals of elemental (native) arsenic are found in nature, although rarely.

Cadet's fuming liquid (impure cacodyl), often claimed as the first synthetic organometallic compound, was synthesized in 1760 by Louis Claude Cadet de Gassicourt through the reaction of potassium acetate with arsenic trioxide.[59]

In the

Two arsenic pigments have been widely used since their discovery –

Applications

Agricultural

The toxicity of arsenic to

Arsenic was also used in various agricultural insecticides and poisons. For example,

The biogeochemistry of arsenic is complex and includes various adsorption and desorption processes. The toxicity of arsenic is connected to its solubility and is affected by pH. Arsenite (AsO3−3) is more soluble than arsenate (AsO3−4) and is more toxic; however, at a lower pH, arsenate becomes more mobile and toxic. It was found that addition of sulfur, phosphorus, and iron oxides to high-arsenite soils greatly reduces arsenic phytotoxicity.[77]

Arsenic is used as a feed additive in poultry and swine production, in particular it was used in the U.S. until 2015 to increase weight gain, improve feed efficiency, and prevent disease.[78][79] An example is roxarsone, which had been used as a broiler starter by about 70% of U.S. broiler growers.[80] In 2011, Alpharma, a subsidiary of Pfizer Inc., which produces roxarsone, voluntarily suspended sales of the drug in response to studies showing elevated levels of inorganic arsenic, a carcinogen, in treated chickens.[81] A successor to Alpharma, Zoetis, continued to sell nitarsone until 2015, primarily for use in turkeys.[81]

A 2006 study of the remains of the

Medical use

During the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, a number of arsenic compounds were used as medicines, including

Arsenic trioxide has been used in a variety of ways since the 15th century, most commonly in the treatment of

A 2008 paper reports success in locating tumors using arsenic-74 (a positron emitter). This isotope produces clearer PET scan images than the previous radioactive agent, iodine-124, because the body tends to transport iodine to the thyroid gland producing signal noise.[87] Nanoparticles of arsenic have shown ability to kill cancer cells with lesser cytotoxicity than other arsenic formulations.[88]

In subtoxic doses, soluble arsenic compounds act as

Alloys

The main use of arsenic is in alloying with lead. Lead components in

Military

After

Other uses

- Copper acetoarsenite was used as a green sweets.[98]

- Arsenic is used in bronzing[99] and pyrotechnics.

- As much as 2% of produced arsenic is used in lead alloys for

- Arsenic is added in small quantities to alpha-brass to make it dezincification-resistant. This grade of brass is used in plumbing fittings and other wet environments.[101]

- Arsenic is also used for taxonomic sample preservation. It was also used in embalming fluids historically.[102]

- Arsenic was used in the taxidermy process up until the 1980s.[103]

- Arsenic was used as an opacifier in ceramics, creating white glazes.[104]

- Until recently, arsenic was used in optical glass. Modern glass manufacturers have ceased using both arsenic and lead.[105][106][107]

- In computers; arsenic is used in the chips as the n-type doping.[108]

Biological role

Bacteria

Some species of bacteria obtain their energy in the absence of oxygen by oxidizing various fuels while reducing arsenate to arsenite. Under oxidative environmental conditions some bacteria use arsenite as fuel, which they oxidize to arsenate.[109] The enzymes involved are known as arsenate reductases (Arr).[110]

In 2008, bacteria were discovered that employ a version of

In 2011, it was postulated that a strain of Halomonadaceae could be grown in the absence of phosphorus if that element were substituted with arsenic,[112] exploiting the fact that the arsenate and phosphate anions are similar structurally. The study was widely criticised and subsequently refuted by independent researcher groups.[113][114]

Essential trace element in higher animals

Arsenic is understood to be an essential trace mineral in birds as it is involved in the synthesis of methionine metabolites, with feeding recommendations being between 0.012 and 0.050 mg/kg.[115]

Some evidence indicates that arsenic is an essential trace mineral in mammals. However, the

Heredity

Arsenic has been linked to

The Chinese brake fern (Pteris vittata) hyperaccumulates arsenic from the soil into its leaves and has a proposed use in phytoremediation.[118]

Biomethylation

Inorganic arsenic and its compounds, upon entering the

Environmental issues

Exposure

Naturally occurring sources of human exposure include volcanic ash, weathering of minerals and ores, and mineralized groundwater. Arsenic is also found in food, water, soil, and air.[123] Arsenic is absorbed by all plants, but is more concentrated in leafy vegetables, rice, apple and grape juice, and seafood.[124] An additional route of exposure is inhalation of atmospheric gases and dusts.[125] During the Victorian era, arsenic was widely used in home decor, especially wallpapers.[126]

Occurrence in drinking water

Extensive arsenic contamination of groundwater has led to widespread

Since the 1980s, residents of the Ba Men region of Inner Mongolia, China have been chronically exposed to arsenic through drinking water from contaminated wells.[132] A 2009 research study observed an elevated presence of skin lesions among residents with well water arsenic concentrations between 5 and 10 µg/L, suggesting that arsenic induced toxicity may occur at relatively low concentrations with chronic exposure.[132] Overall, 20 of China's 34 provinces have high arsenic concentrations in the groundwater supply, potentially exposing 19 million people to hazardous drinking water.[133]

A study by IIT Kharagpur found high levels of Arsenic in groundwater of 20% of India's land, exposing more than 250 million people. States such as Punjab, Bihar, West Bengal, Assam, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, and Gujarat have highest land area exposed to arsenic.[134]

In the United States, arsenic is most commonly found in the ground waters of the southwest.[135] Parts of New England, Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota and the Dakotas are also known to have significant concentrations of arsenic in ground water.[136] Increased levels of skin cancer have been associated with arsenic exposure in Wisconsin, even at levels below the 10 ppb drinking water standard.[137] According to a recent film funded by the US Superfund, millions of private wells have unknown arsenic levels, and in some areas of the US, more than 20% of the wells may contain levels that exceed established limits.[138]

Low-level exposure to arsenic at concentrations of 100 ppb (i.e., above the 10 ppb drinking water standard) compromises the initial immune response to H1N1 or swine flu infection according to NIEHS-supported scientists. The study, conducted in laboratory mice, suggests that people exposed to arsenic in their drinking water may be at increased risk for more serious illness or death from the virus.[139]

Some Canadians are drinking water that contains inorganic arsenic. Private-dug–well waters are most at risk for containing inorganic arsenic. Preliminary well water analysis typically does not test for arsenic. Researchers at the Geological Survey of Canada have modeled relative variation in natural arsenic hazard potential for the province of New Brunswick. This study has important implications for potable water and health concerns relating to inorganic arsenic.[140]

Epidemiological evidence from Chile shows a dose-dependent connection between chronic arsenic exposure and various forms of cancer, in particular when other risk factors, such as cigarette smoking, are present. These effects have been demonstrated at contaminations less than 50 ppb.[141] Arsenic is itself a constituent of tobacco smoke.[142]

Analyzing multiple epidemiological studies on inorganic arsenic exposure suggests a small but measurable increase in risk for bladder cancer at 10 ppb.[143] According to Peter Ravenscroft of the Department of Geography at the University of Cambridge,[144] roughly 80 million people worldwide consume between 10 and 50 ppb arsenic in their drinking water. If they all consumed exactly 10 ppb arsenic in their drinking water, the previously cited multiple epidemiological study analysis would predict an additional 2,000 cases of bladder cancer alone. This represents a clear underestimate of the overall impact, since it does not include lung or skin cancer, and explicitly underestimates the exposure. Those exposed to levels of arsenic above the current WHO standard should weigh the costs and benefits of arsenic remediation.

Early (1973) evaluations of the processes for removing dissolved arsenic from drinking water demonstrated the efficacy of co-precipitation with either iron or aluminium oxides. In particular, iron as a coagulant was found to remove arsenic with an efficacy exceeding 90%.[145][146] Several adsorptive media systems have been approved for use at point-of-service in a study funded by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) and the National Science Foundation (NSF). A team of European and Indian scientists and engineers have set up six arsenic treatment plants in West Bengal based on in-situ remediation method (SAR Technology). This technology does not use any chemicals and arsenic is left in an insoluble form (+5 state) in the subterranean zone by recharging aerated water into the aquifer and developing an oxidation zone that supports arsenic oxidizing micro-organisms. This process does not produce any waste stream or sludge and is relatively cheap.[147]

Another effective and inexpensive method to avoid arsenic contamination is to sink wells 500 feet or deeper to reach purer waters. A recent 2011 study funded by the US National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences' Superfund Research Program shows that deep sediments can remove arsenic and take it out of circulation. In this process, called adsorption, arsenic sticks to the surfaces of deep sediment particles and is naturally removed from the ground water.[148]

Magnetic separations of arsenic at very low magnetic field

Epidemiological studies have suggested a correlation between chronic consumption of drinking water contaminated with arsenic and the incidence of all leading causes of mortality.[150] The literature indicates that arsenic exposure is causative in the pathogenesis of diabetes.[151]

Chaff-based filters have recently been shown to reduce the arsenic content of water to 3 µg/L. This may find applications in areas where the potable water is extracted from underground aquifers.[152]

San Pedro de Atacama

For several centuries, the people of San Pedro de Atacama in Chile have been drinking water that is contaminated with arsenic, and some evidence suggests they have developed some immunity.[153][154][155]

Hazard maps for contaminated groundwater

Around one-third of the world's population drinks water from groundwater resources. Of this, about 10 percent, approximately 300 million people, obtains water from groundwater resources that are contaminated with unhealthy levels of arsenic or fluoride.[156] These trace elements derive mainly from minerals and ions in the ground.[157][158]

Redox transformation of arsenic in natural waters

Arsenic is unique among the trace

Arsenic may be solubilized by various processes. When pH is high, arsenic may be released from surface binding sites that lose their positive charge. When water level drops and sulfide minerals are exposed to air, arsenic trapped in sulfide minerals can be released into water. When organic carbon is present in water, bacteria are fed by directly reducing As(V) to As(III) or by reducing the element at the binding site, releasing inorganic arsenic.[160]

The aquatic transformations of arsenic are affected by pH, reduction-oxidation potential, organic matter concentration and the concentrations and forms of other elements, especially iron and manganese. The main factors are pH and the redox potential. Generally, the main forms of arsenic under oxic conditions are H3AsO4, H2AsO4−, HAsO42−, and AsO43− at pH 2, 2–7, 7–11 and 11, respectively. Under reducing conditions, H3AsO4 is predominant at pH 2–9.

Oxidation and reduction affects the migration of arsenic in subsurface environments. Arsenite is the most stable soluble form of arsenic in reducing environments and arsenate, which is less mobile than arsenite, is dominant in oxidizing environments at neutral pH. Therefore, arsenic may be more mobile under reducing conditions. The reducing environment is also rich in organic matter which may enhance the solubility of arsenic compounds. As a result, the adsorption of arsenic is reduced and dissolved arsenic accumulates in groundwater. That is why the arsenic content is higher in reducing environments than in oxidizing environments.[161]

The presence of sulfur is another factor that affects the transformation of arsenic in natural water. Arsenic can

Redox reactions involving Fe also appear to be essential factors in the fate of arsenic in aquatic systems. The reduction of iron oxyhydroxides plays a key role in the release of arsenic to water. So arsenic can be enriched in water with elevated Fe concentrations.[162] Under oxidizing conditions, arsenic can be mobilized from pyrite or iron oxides especially at elevated pH. Under reducing conditions, arsenic can be mobilized by reductive desorption or dissolution when associated with iron oxides. The reductive desorption occurs under two circumstances. One is when arsenate is reduced to arsenite which adsorbs to iron oxides less strongly. The other results from a change in the charge on the mineral surface which leads to the desorption of bound arsenic.[163]

Some species of bacteria catalyze redox transformations of arsenic. Dissimilatory arsenate-respiring prokaryotes (DARP) speed up the reduction of As(V) to As(III). DARP use As(V) as the electron acceptor of anaerobic respiration and obtain energy to survive. Other organic and inorganic substances can be oxidized in this process.

Equilibrium thermodynamic calculations predict that As(V) concentrations should be greater than As(III) concentrations in all but strongly reducing conditions, i.e. where SO42− reduction is occurring. However, abiotic redox reactions of arsenic are slow. Oxidation of As(III) by dissolved O2 is a particularly slow reaction. For example, Johnson and Pilson (1975) gave half-lives for the oxygenation of As(III) in seawater ranging from several months to a year.[165] In other studies, As(V)/As(III) ratios were stable over periods of days or weeks during water sampling when no particular care was taken to prevent oxidation, again suggesting relatively slow oxidation rates. Cherry found from experimental studies that the As(V)/As(III) ratios were stable in anoxic solutions for up to 3 weeks but that gradual changes occurred over longer timescales.[166] Sterile water samples have been observed to be less susceptible to speciation changes than non-sterile samples.[167] Oremland found that the reduction of As(V) to As(III) in Mono Lake was rapidly catalyzed by bacteria with rate constants ranging from 0.02 to 0.3-day−1.[168]

Wood preservation in the US

As of 2002, US-based industries consumed 19,600 metric tons of arsenic. Ninety percent of this was used for treatment of wood with

Although discontinued, this application is also one of the most concerning to the general public. The vast majority of older

Mapping of industrial releases in the US

One tool that maps the location (and other information) of arsenic releases in the United States is

Bioremediation

Physical, chemical, and biological methods have been used to remediate arsenic contaminated water.[177] Bioremediation is said to be cost-effective and environmentally friendly.[178] Bioremediation of ground water contaminated with arsenic aims to convert arsenite, the toxic form of arsenic to humans, to arsenate. Arsenate (+5 oxidation state) is the dominant form of arsenic in surface water, while arsenite (+3 oxidation state) is the dominant form in hypoxic to anoxic environments. Arsenite is more soluble and mobile than arsenate. Many species of bacteria can transform arsenite to arsenate in anoxic conditions by using arsenite as an electron donor.[179] This is a useful method in ground water remediation. Another bioremediation strategy is to use plants that accumulate arsenic in their tissues via phytoremediation but the disposal of contaminated plant material needs to be considered.

Bioremediation requires careful evaluation and design in accordance with existing conditions. Some sites may require the addition of an electron acceptor while others require microbe supplementation (bioaugmentation). Regardless of the method used, only constant monitoring can prevent future contamination.

Arsenic removal

Coagulation and flocculation

Coagulation and flocculation are closely related processes common in arsenate removal from water. Due to the net negative charge carried by arsenate ions, they settle slowly or do not settle at all due to charge repulsion. In coagulation, a positively charged coagulent such as Fe and Alum (common used salts: FeCl3,[180] Fe2(SO4)3,[181] Al2(SO4)3[182]) neutralise the negatively charged arsenate, enable it to settle. Flocculation follows where an flocculant bridge smaller particles and allows the aggregate to precipitate out from water. However, such methods may not be efficient on arsenite as As(III) exist in uncharged arsenious acid, H3AsO3, at near neutral pH.[183]

The major drawbacks of coagulation and flocculation is the costly disposal of arsenate-concentrated sludge, and possible secondary contamination of environment. Moreover, coagulents such as Fe may produce ion contamination that exceeds safety level.[180]

Toxicity and precautions

| Hazards | |

|---|---|

| GHS labelling:[184] | |

| |

| Danger | |

| H301+H331, H315, H318, H350, H410 | |

| P273, P280, P301+P310, P302+P352, P304+P340+P311, P305+P351+P338 | |

Arsenic and many of its compounds are especially potent poisons. Small amount of arsenic can be detected by pharmacopoial methods which includes reduction of arsenic to arsenious with help of zinc and can be confirmed with mercuric chloride paper.[185]

Classification

Elemental arsenic and arsenic sulfate and trioxide compounds are classified as "toxic" and "dangerous for the environment" in the European Union under directive 67/548/EEC. The

Arsenic is known to cause arsenicosis when present in drinking water, "the most common species being arsenate [HAsO2−4; As(V)] and arsenite [H3AsO3; As(III)]".

Legal limits, food, and drink

In the United States since 2006, the maximum concentration in drinking water allowed by the

In 2008, based on its ongoing testing of a wide variety of American foods for toxic chemicals,[191] the U.S. Food and Drug Administration set the "level of concern" for inorganic arsenic in apple and pear juices at 23 ppb, based on non-carcinogenic effects, and began blocking importation of products in excess of this level; it also required recalls for non-conforming domestic products.[187] In 2011, the national Dr. Oz television show broadcast a program highlighting tests performed by an independent lab hired by the producers. Though the methodology was disputed (it did not distinguish between organic and inorganic arsenic) the tests showed levels of arsenic up to 36 ppb.[192] In response, the FDA tested the worst brand from the Dr. Oz show and found much lower levels. Ongoing testing found 95% of the apple juice samples were below the level of concern. Later testing by Consumer Reports showed inorganic arsenic at levels slightly above 10 ppb, and the organization urged parents to reduce consumption.[193] In July 2013, on consideration of consumption by children, chronic exposure, and carcinogenic effect, the FDA established an "action level" of 10 ppb for apple juice, the same as the drinking water standard.[187]

Concern about arsenic in rice in Bangladesh was raised in 2002, but at the time only Australia had a legal limit for food (one milligram per kilogram, or 1000 ppb).[194][195] Concern was raised about people who were eating U.S. rice exceeding WHO standards for personal arsenic intake in 2005.[196] In 2011, the People's Republic of China set a food standard of 150 ppb for arsenic.[197]

In the United States in 2012, testing by separate groups of researchers at the Children's Environmental Health and Disease Prevention Research Center at Dartmouth College (early in the year, focusing on urinary levels in children)[198] and Consumer Reports (in November)[199][200] found levels of arsenic in rice that resulted in calls for the FDA to set limits.[201] The FDA released some testing results in September 2012,[202][203] and as of July 2013, is still collecting data in support of a new potential regulation. It has not recommended any changes in consumer behavior.[204]

Consumer Reports recommended:

- That the EPA and FDA eliminate arsenic-containing fertilizer, drugs, and pesticides in food production;

- That the FDA establish a legal limit for food;

- That industry change production practices to lower arsenic levels, especially in food for children; and

- That consumers test home water supplies, eat a varied diet, and cook rice with excess water, then draining it off (reducing inorganic arsenic by about one third along with a slight reduction in vitamin content).[200]

- Evidence-based public health advocates also recommend that, given the lack of regulation or labeling for arsenic in the U.S., children should eat no more than 1.5 servings per week of rice and should not drink rice milk as part of their daily diet before age 5.[205] They also offer recommendations for adults and infants on how to limit arsenic exposure from rice, drinking water, and fruit juice.[205]

A 2014 World Health Organization advisory conference was scheduled to consider limits of 200–300 ppb for rice.[200]

Reducing arsenic content in rice

In 2020, scientists assessed multiple preparation procedures of rice for their capacity to reduce arsenic content and preserve nutrients, recommending a procedure involving parboiling and water-absorption.[207][206][208]

Occupational exposure limits

| Country | Limit[209] |

|---|---|

| Argentina | Confirmed human carcinogen |

| Australia | TWA 0.05 mg/m3 – Carcinogen |

| Belgium | TWA 0.1 mg/m3 – Carcinogen |

| Bulgaria | Confirmed human carcinogen |

| Canada | TWA 0.01 mg/m3 |

| Colombia | Confirmed human carcinogen |

| Denmark | TWA 0.01 mg/m3 |

| Finland | Carcinogen |

| Egypt | TWA 0.2 mg/m3 |

| Hungary | Ceiling concentration 0.01 mg/m3 – Skin, carcinogen |

| India | TWA 0.2 mg/m3 |

| Japan | Group 1 carcinogen |

| Jordan | Confirmed human carcinogen |

| Mexico | TWA 0.2 mg/m3 |

| New Zealand | TWA 0.05 mg/m3 – Carcinogen |

| Norway | TWA 0.02 mg/m3 |

| Philippines | TWA 0.5 mg/m3 |

| Poland | TWA 0.01 mg/m3 |

| Singapore | Confirmed human carcinogen |

| South Korea | TWA 0.01 mg/m3[210][211] |

| Sweden | TWA 0.01 mg/m3 |

| Thailand | TWA 0.5 mg/m3 |

| Turkey | TWA 0.5 mg/m3 |

| United Kingdom | TWA 0.1 mg/m3 |

| United States | TWA 0.01 mg/m3 |

| Vietnam | Confirmed human carcinogen |

Ecotoxicity

Arsenic is bioaccumulative in many organisms, marine species in particular, but it does not appear to biomagnify significantly in food webs.[212] In polluted areas, plant growth may be affected by root uptake of arsenate, which is a phosphate analog and therefore readily transported in plant tissues and cells. In polluted areas, uptake of the more toxic arsenite ion (found more particularly in reducing conditions) is likely in poorly-drained soils.

Toxicity in animals

| Compound | Animal | LD50 | Route |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arsenic | Rat | 763 mg/kg | oral |

| Arsenic | Mouse | 145 mg/kg | oral |

| Calcium arsenate | Rat | 20 mg/kg | oral |

| Calcium arsenate | Mouse | 794 mg/kg | oral |

| Calcium arsenate | Rabbit | 50 mg/kg | oral |

| Calcium arsenate | Dog | 38 mg/kg | oral |

Lead arsenate

|

Rabbit | 75 mg/kg | oral |

| Compound | Animal | LD50[213] | Route |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arsenic trioxide (As(III)) | Mouse | 26 mg/kg | oral |

| Arsenite (As(III)) | Mouse | 8 mg/kg | im |

| Arsenate (As(V)) | Mouse | 21 mg/kg | im |

| MMA (As(III)) | Hamster | 2 mg/kg | ip |

| MMA (As(V)) | Mouse | 916 mg/kg | oral |

| DMA (As(V)) | Mouse | 648 mg/kg | oral |

| im = injected intramuscularly

ip = administered intraperitoneally | |||

Biological mechanism

Arsenic's toxicity comes from the affinity of arsenic(III) oxides for thiols. Thiols, in the form of cysteine residues and cofactors such as lipoic acid and coenzyme A, are situated at the active sites of many important enzymes.[11]

Arsenic disrupts

Exposure risks and remediation

Occupational exposure and arsenic poisoning may occur in persons working in industries involving the use of inorganic arsenic and its compounds, such as wood preservation, glass production, nonferrous metal alloys, and electronic semiconductor manufacturing. Inorganic arsenic is also found in coke oven emissions associated with the smelter industry.[214]

The conversion between As(III) and As(V) is a large factor in arsenic environmental contamination. According to Croal, Gralnick, Malasarn and Newman, "[the] understanding [of] what stimulates As(III) oxidation and/or limits As(V) reduction is relevant for bioremediation of contaminated sites (Croal). The study of chemolithoautotrophic As(III) oxidizers and the heterotrophic As(V) reducers can help the understanding of the oxidation and/or reduction of arsenic.[215]

Treatment

Treatment of chronic arsenic poisoning is possible. British anti-lewisite (dimercaprol) is prescribed in doses of 5 mg/kg up to 300 mg every 4 hours for the first day, then every 6 hours for the second day, and finally every 8 hours for 8 additional days.[216] However the USA's Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) states that the long-term effects of arsenic exposure cannot be predicted.[125] Blood, urine, hair, and nails may be tested for arsenic; however, these tests cannot foresee possible health outcomes from the exposure.[125] Long-term exposure and consequent excretion through urine has been linked to bladder and kidney cancer in addition to cancer of the liver, prostate, skin, lungs, and nasal cavity.[217]

See also

References

- ^ "Standard Atomic Weights: Arsenic". CIAAW. 2013.

- ISSN 1365-3075.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-62708-155-9.

- ^ .

- PMID 19937872.

- PMID 15360247.

- ISBN 978-0-87170-768-0. pdf.

- ISBN 0849304814.

- ISBN 0-8493-0464-4.

- .

- ^ ISBN 978-3527306732.

- ^ a b Anke M. (1986) "Arsenic", pp. 347–372 in Mertz W. (ed.), Trace elements in human and Animal Nutrition, 5th ed. Orlando, FL: Academic Press

- ^ S2CID 22882255.

- Uthus E.O. (1994) "Arsenic essentiality and factors affecting its importance", pp. 199–208 in Chappell W.R, Abernathy C.O, Cothern C.R. (eds.) Arsenic Exposure and Health. Northwood, UK: Science and Technology Letters.

Arsenic was nicknamed 'the inheritance powder' as it was commonly used to poison family members for a fortune in the Renaissance era.

At first, green papers were coloured with the traditional mineral pigment verdigris or buy mixing blues and yellows of plant origin. But once Scheele's green began to be produced in quantity, it was adopted as an improvement over the old colours and became a common constituent in wallpaper by 1800.

The wallpaper-as-arsenic-source of poison made the headlines in 1982 [...] when analysis of a sample of wallpaper from the living room in Longwood, Napoleon's residence on St. Helena, revealed arsenic concentrations of about 0.12 g/m2.

- Fred Campbell (11 August 2008). "Arsenic-loving bacteria rewrite photosynthesis rules". Chemistry World.

Bibliography

- Emsley J (2011). "Arsenic". Nature's Building Blocks: An A–Z Guide to the Elements. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. pp. 47–55. ISBN 978-0-19-960563-7.

- ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- Rieuwerts, John (2015). The Elements of Environmental Pollution. Abingdon and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-85920-2.

Further reading

- Whorton JG (2011). The Arsenic Century. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-960599-6.

External links

- WHO fact sheet on arsenic

- Arsenic Cancer Causing Substances, U.S. National Cancer Institute.

- CTD's Arsenic page and CTD's Arsenicals page from the Comparative Toxicogenomics Database

- Contaminant Focus: Arsenic Archived 1 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine by the EPA.

- Environmental Health Criteria for Arsenic and Arsenic Compounds, 2001 by the WHO.

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health – Arsenic Page