Art Nouveau in Brussels

Henry Van de Velde (1898); Bottom: Stoclet Palace by Josef Hoffmann (1905–1911) | |

| Years active | c. 1890–1910 |

|---|---|

| Location | Belgium |

The Art Nouveau movement of architecture and design first appeared in Brussels, Belgium, in the early 1890s, and quickly spread to France and to the rest of Europe. It began as a reaction against the formal vocabulary of European academic art, eclecticism and historicism of the 19th century, and was based upon an innovative use of new materials, such as iron and glass, to open larger interior spaces and provide maximum light; curving lines such as the whiplash line; and other designs inspired by plants and other natural forms.

The early Art Nouveau designers in Brussels created not only art and architecture but also furniture, glassware, carpets, and even clothing and other decoration to match. Some of Brussels' municipalities, such as Schaerbeek, Etterbeek, Ixelles, and Saint-Gilles, were developed during the heyday of Art Nouveau and have many buildings in that style. After 1900, the style gradually became more formal and geometric. The final Art Nouveau landmark in Brussels was the Stoclet Palace by the Austrian-Moravian architect Josef Hoffmann (1905–1911), now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, which marked the transition to a more geometric and formal style and the birth of Art Deco and early modernism.[1]

In spite of

Architecture

Paul Hankar

The first two Art Nouveau houses in Brussels were built at the same time, in 1892–93, by the architects and designers

In 1893, Hankar designed and built the

In 1897, Hankar designed one more important project: he was the artistic director for the

-

Facade of the Hankar House by Paul Hankar (1893)

-

Former Chemiserie Niguet storefront on the Rue Royale/Koningsstraat by Hankar (1896)

-

Hôtel Albert Ciamberlani by Hankar, with sgraffito murals (1897–98)

Victor Horta

At the same time Hankar was working on his house, Victor Horta (1861–1947) was building a very different kind of Art Nouveau house in Brussels, the Hôtel Tassel, for the scientist and professor Émile Tassel.[4] Horta, born in Ghent, was the son of a shoemaker, who had studied architecture at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Ghent, then at the Academy of Fine Arts in Brussels. He subsequently worked for the neoclassical architect Alphonse Balat, who was in the midst of constructing the enormous glass and iron Royal Greenhouses of Laeken in northern Brussels for King Leopold II. As his assistant, Horta learned how to use glass, iron, and later steel, materials he used skilfully in all of his later buildings.[2]

Hôtel Tassel (1892–93)

The Hôtel Tassel, completed in 1893, was on a relatively narrow lot, and the facade, designed to harmonise with the neighbouring buildings, was well-crafted but not revolutionary. The extraordinary part was the interior, designed with an open floor plan, and with an innovative use of iron columns and glass windows and skylights, and of decoration, to create a new idea of interior space.[5][6] The house was built around an open central stairway. The interior decoration featured curling lines, modelled after vines and flowers, which were repeated in the ironwork railings of the stairway, in the tiles of the floor, in the glass of the doors and skylights, and painted on the walls. The building is widely recognised as one of the first appearances of Art Nouveau in architecture (along with the Hankar House by Paul Hankar, built at the same time).[7][4][8] In 2000, it was designated, along with three other town houses designed soon afterwards, as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. In designating these sites, UNESCO explained: "The stylistic revolution represented by these works is characterised by their open plan, the diffusion of light, and the brilliant joining of the curved lines of decoration with the structure of the building."[9]

-

Facade of the Hôtel Tassel by Victor Horta (1892–93)

-

Stairway of the Hôtel Tassel

-

Floor of the Hôtel Tassel, with the characteristic curling vegetal design

Other works

Horta built several more town houses in variations of the style, each with its own original character. They include the Hôtel Winssinger (1895–96), the Hôtel Deprez-Van de Velde (1895–96), the Hôtel Solvay (1895–1900), the Hôtel van Eetvelde (1895–1901), and the Hôtel Aubecq (1900), as well as his own residence (1898–1901), which is now the Horta Museum. He applied the same original combination of a steel frame, open plan, skylights and functional features, without the decoration and luxury materials, for several larger buildings, including the headquarters of the Belgian Workers' Party (POB/BWP) or Maison du Peuple/Volkshuis (built in 1896–1899, and demolished in 1965). He also designed several commercial buildings, including the À L'Innovation department store (1901), which burnt down in 1967 (see L'Innovation department store fire), as well as a large fabric store, the Magasins Waucquez (1905–1906), which is now the Belgian Comic Strip Center.

After about 1910, Art Nouveau features gradually disappeared from Horta's work, as his style evolved into a fusion of neoclassicism and early modernism. Major later buildings include the Centre for Fine Arts, as well as Brussels-Central railway station, which he began in 1910 and was still working on when he died in 1947.[10]

-

Autrique House by Victor Horta(1893)

-

Facade of the Maison du Peuple/Volkshuis by Horta (1896–1899)

-

Hôtel Solvay by Horta (1895–1900)

-

Entrance of the Hôtel Solvay

-

Hôtel van Eetvelde by Horta (1895–1901)

-

Horta's residence and studio, now the Horta Museum (1898–1901)

-

À L'Innovation department store, pictured soon after its opening in 1901

Henry Van de Velde

Another major figure in Brussels Art Nouveau was

Josef Hoffmann and the Stoclet Palace (1905–1911)

Brussels has the earliest Art Nouveau houses, and also the finest example of a late Art Nouveau or Vienna Secession house, the Stoclet Palace (1905–1911), by Josef Hoffmann, in the Woluwe-Saint-Pierre municipality. The building has virtually nothing in common with the first Art Nouveau houses, except a certain audacity and willingness to break all the previous styles' rules. It was built for the Brussels banker and art collector Adolphe Stoclet, who met Hoffmann in Vienna, and was impressed by his work. The exterior of the Palace is assembled out of large marble cubes, mounting to a tower. The only decoration on the exterior is a small work of sculpture by Franz Metzner over a doorway, and narrow, stylised bands of sculpture accenting the cubes' horizontal and vertical edges.

The interior is much more lavish, with a richness of varied stones and woods, but it is also incessantly geometric. The most famous feature is the ceramic frieze in the dining room by the Austrian symbolist painter Gustav Klimt.[12] The house was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2009.[1]

-

Stoclet Palace by Josef Hoffmann (1905–1911)

-

Windows of the Stoclet Palace

-

Detail of the facade, made of reinforced concrete covered with marble plaques

-

Photograph of the Stoclet Palace's dining room, with furniture by Hoffmann and ceramic frieze by Gustav Klimt

Other notable Brussels architects

Other notable Art Nouveau architects in Brussels include:

- balustrades with curling lines. His most famous work is the former Old England department store (1898–99), on the Rue Montagne de la Cour/Hofberg, in central Brussels, now the Musical Instruments Museum (MIM). It features natural light, rich decoration of iron grill-work and ceramic tiles, and an open floor plan. In 1899, he also completed the first apartment building in Brussels built of reinforced concrete.[13]

- Léon Sneyers (1877–1958). Sneyers was trained by Hankar, and then became his collaborator, working in particular on the Belgian participation in the 1902 Turin Exposition of Decorative Arts, which brought Belgian design to a wider European audience. He designed many displays for expositions across Europe. He was attracted to the style of the Wiener Werkstätte, and ran a gallery that promoted their products in Brussels.[14]

- Gustave Strauven (1878–1919). Strauven began his career as an assistant designer working with Horta, before he started his own practice at age 21, making some of the most extravagant Art Nouveau buildings in Brussels. His most famous work is the Saint-Cyr House at 11, square Ambiorix/Ambiorixsquare (1901–1903). The house is only 4 metres (13 ft) wide, but is given extraordinary height by his elaborate architectural inventions. It is entirely covered by polychrome bricks and a network of curling vegetal forms in wrought iron, in a virtually Art Nouveau-Baroque style.[15]

- Paul Cauchie (1875–1952). Cauchie was an architect, decorator, painter, furniture designer, and a specialist in sgraffito, the Renaissance technique of decorating a facade with murals made of tinted plaster applied to a wet surface. He founded his own enterprise in Brussels in 1896 to decorate houses with this technique, which was widely used in the Art Nouveau period. He designed his own house in 1905, at 5, rue des Francs/Frankenstraat, with a facade almost entirely covered with sgraffito. He also decorated the interior with friezes, furniture and woodwork he had designed.[16]

-

Former Old England department store by Paul Saintenoy (1898–99)

-

Saint-Cyr House by Gustave Strauven (1901–1903)

-

La Marjolaine storefront by Léon Sneyers (1904)

-

House of the architect Paul Cauchie with sgraffito decoration (1905)

-

Villa Beau-Site, house of the architect Arthur Nelissen (1905)

-

Bay window on the first floor of Villa Beau-Site

-

Asymmetric facade with curved lines of the De Beck building by Strauven (1905)

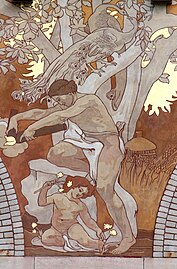

Painting and Sgraffito

One particular aspect of Brussels' Art Nouveau was the use of sgraffito for exterior or interior decoration. This was a technique invented during the Renaissance, involving applying layers of tinted plaster to a damp wall. It was used in particular by architect Paul Hankar on the facades of houses. The artist-decorator Paul Cauchie made sgraffito for the facade of his own residence, as did the painter Albert Ciamberlani.

-

Sgraffito by Cauchie on the Rue Malibran/Malibranstraat (1900)

-

Sgraffito by Cauchie on his residence and studio (1905)

-

Sgraffito panel in the Cauchie House

-

Preparatory painting for dining room of the Stoclet Palace by Gustav Klimt (1905–1911)

Glass art

-

Drawing for Les Chardons ("The Thistles") vase by Philippe Wolfers (1896)

-

Vase by Wolfers (1899)

-

Crépuscule ("Twilight") vase with bat design by Wolfers (1901)

Another feature of Brussels' Art Nouveau was the use of stained glass windows with that style of floral themes in residential salons. Victor Horta used stained glass windows, combined with ceramics, wood and iron decoration with similar motifs, to create a harmony between functional elements and decoration, making a unified work of art or Gesamtkunstwerk ("total work of art"). One example is the stained glass window of the doorway of the Hôtel van Eetvelde (1895).

-

Doorway window of the Hôtel van Eetvelde by Victor Horta (1895)

-

Skylight above the stairway of the Horta Museum (1898–1901)

-

Furnishings of the Hôtel Aubecq by Horta (1899–1902) on display at the Musée d'Orsay, Paris

-

Detail of La Marjolaine storefront by Léon Sneyers (1904)

Metal art

Art Nouveau architecture made use of many technological innovations of the late 19th century, especially the use of exposed iron and large, irregularly shaped pieces of glass for architecture. The French architectural theorist Eugène Viollet-le-Duc had advocated showing, rather than concealing the iron frameworks of modern buildings, but Brussels' Art Nouveau architects went a step further: they added iron decoration in curves inspired by floral and vegetal forms both in the interiors and exteriors of their buildings. They took the form of stairway railings, light fixtures, and other details in the interior, as well as balconies and other ornaments on the exterior.[19]

Victor Horta, who had worked on the construction of iron and glass Royal Greenhouses of Laeken, was one of the first to create Art Nouveau ironwork. His use of wrought iron or cast iron in scrolling whiplash forms on doorways, balconies and gratings became some of the most distinctive features of Art Nouveau architecture. The use of metal decoration in vegetal forms soon also appeared in silverware, lamps, and other decorative items.[19]

-

Detail of the Winter Garden of the Hôtel van Eetvelde by Victor Horta (1898–1900)

-

Spiral staircase in the Horta Museum (1898–1901)

-

Light fixture by Horta (1903)

-

Gate of the Stoclet Palace by Josef Hoffmann (1905–1911)

Furniture and decoration

Many Brussels architects, including

Another notable figure in early Belgian Art Nouveau furniture and design was

-

Furniture designed byHenry Van de Velde for the Villa Bloemenwerf(1895)

-

Chair by Van de Velde for the Villa Bloemenwerf (1895)

-

Desk, chair and lamps by Van de Velde (1898–99) (Musée d'Orsay, Paris)

-

Dining room furniture and wall panel by Victor Horta from the Hôtel Aubecq (1899–1902), now in the Musée d'Orsay

-

Chair by Horta from the Hôtel Aubecq, now in the Musée d'Orsay

-

Dining room by Horta displayed at the 1902 Turin International Exposition

-

Table designed by Horta, probably for the 1902 Turin Exposition

-

Peacock Chair by Horta from either the Hôtel Tassel or the Castle of La Hulpe

-

Mahogany chair by Horta (1900) (Cleveland Museum of Art)

Jewellery

The most prominent Art Nouveau

-

Plumes de Paon ("Peacock Feathers"), belt buckle by Wolfers (1898)

-

Cygne et Serpents ("Swan and Serpents"), pendant by Wolfers (1899–1900)

Protection status

Among Brussels' Art Nouveau creations, four buildings by

The

See also

- Art Nouveau in Antwerp

- Art Deco in Brussels

- History of Brussels

- Culture of Belgium

- Belgium in the long nineteenth century

References

Citations

- ^ a b c "Stoclet House". whc.unesco.org. UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ a b c Culot & Pirlot 2005, p. 74.

- ^ Culot & Pirlot 2005, p. 74–75.

- ^ a b Oudin 1994, p. 237.

- ^ [1] Victor Horta - Encyclopaedia Britannica

- ^ Oudin 1994.

- ^ Giedion 1941.

- ^ Sembach 2013, p. 47.

- ^ a b "Major Town Houses of the Architect Victor Horta (Brussels)". whc.unesco.org. UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- ^ Culot & Pirlot 2005, p. 78–79.

- ^ Culot & Pirlot 2005, p. 89–90.

- ^ Sembach 2013, p. 230–235.

- ^ Culot & Pirlot 2005, p. 85–90.

- ^ Culot & Pirlot 2005, p. 86–87.

- ^ Culot & Pirlot 2005, p. 87.

- ^ Culot & Pirlot 2005, p. 67.

- ^ Thiébaut 2007, p. 238.

- ^ Fahr-Becker 2015, p. 151–152.

- ^ a b Riley 2004, p. 322.

- ^ Sembach 2013, p. 45.

- ^ Fahr-Becker 2015, p. 152.

Bibliography

- Culot, Maurice; Pirlot, Anne-Marie (2005). Bruxelles Art Nouveau (in French). Brussels: Archives d'Architecture Moderne. ISBN 978-2-87143-126-8.

- Fahr-Becker, Gabriele (2015). Art Nouveau. Rheinbreitbach: H.F. Ullmann. ISBN 978-3-8480-0834-6.

- Giedion, Sigfried (1941). Space Time and Architecture. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-67403-047-3.

- Oudin, Bernard (1994). Dictionnaire des Architectes (in French). Paris: Seghers. ISBN 978-2-232-10398-8.

- Riley, Noël (2004). Grammaire des Arts Décoratifs (in French). Paris: Flammarion. ISBN 978-2-08-011327-6.

- Sembach, Klaus-Jürgen (2013). L'Art Nouveau- L'Utopie de la Réconciliation (in French). Cologne: Taschen. ISBN 978-3-8228-3005-5.

- Thiébaut, Olivier (2007). Un Ensemble Art Nouveau - La Donation Rispal (in French). Paris: Musée d'Orsay - Flammarion. ISBN 978-2-08-011608-6.

- Victoir, Jef; Vanderperren, Jos (1992). Henri Beyaert: Du classicisme à l’art nouveau (in French). St Martens-Latem: Editions de la Dyle. ISBN 978-90-801124-1-4.

External links

Media related to Art Nouveau in Brussels at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Art Nouveau in Brussels at Wikimedia Commons