Art of ancient Egypt

| History of art |

|---|

Ancient Egyptian art refers to art produced in ancient Egypt between the 6th millennium BC and the 4th century AD, spanning from Prehistoric Egypt until the Christianization of Roman Egypt. It includes paintings, sculptures, drawings on papyrus, faience, jewelry, ivories, architecture, and other art media. It was a conservative tradition whose style changed very little over time. Much of the surviving examples comes from tombs and monuments, giving insight into the ancient Egyptian afterlife beliefs.

The

Art of Pre-Dynastic Egypt (6000–3000 BC)

Pre-Dynastic Egypt, corresponding to the

Continued expansion of the desert forced the early ancestors of the Egyptians to settle around the Nile and adopt a more sedentary lifestyle during the Neolithic. The period from 9000 to 6000 BC has left very little archaeological evidence, but around 6000 BC, Neolithic settlements began to appear all over Egypt.[1] Studies based on morphological,[2] genetic,[3] and archaeological data[4] have attributed these settlements to migrants from the Fertile Crescent returning during the Neolithic Revolution, bringing agriculture to the region.[5]

Merimde culture (5000–4200 BC)

From about 5000 to 4200 BC, the Merimde culture, known only from a large settlement site at the edge of the Western Nile Delta, flourished in Lower Egypt. The culture has strong connections to the Faiyum A culture as well as the Levant. People lived in small huts, produced simple undecorated pottery, and had stone tools. Cattle, sheep, goats, and pigs were raised, and wheat, sorghum and barley were planted. The Merimde people buried their dead within the settlement and produced clay figurines.[6] The first Egyptian life-size head made of clay comes from Merimde.[7]

Badarian culture (4400–4000 BC)

The

-

A Badarian burial. 4500–3850 BC

-

Mortuary figurine of a woman; 4400–4000 BC; crocodile bone; height: 8.7 cm; Louvre

-

String of beads; 4400–3800 BC; the beads are made of bone, serpentinite and shell; length: 15 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Vase in the shape of a hippopotamus. Early Predynastic, Badarian. 5th millennium BC

Naqada culture (4000–3000 BC)

The

Naqada I

The Amratian (

-

OvoidNaqada I(Amratian) black-topped terracotta vase, (c. 3800–3500 BC)

-

Figurine of a bearded man; 3800–3500 BC; breccia; from Upper Egypt; Musée des Confluences (Lyon, France)

-

White cross-lined bowl with four legs; 3700–3500 BC; painted pottery; height: 15.6 cm, diameter: 19.7 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Naqada II

The

During this period, distinctly foreign objects and art forms entered Egypt, indicating contact with several parts of Asia, particularly with Mesopotamia. Objects such as the

The route of this trade is difficult to determine, but contact with

The fact that so many Gerzean sites are at the mouths of wadis which lead to the Red Sea may indicate some amount of trade via the Red Sea (though Byblian trade potentially could have crossed the Sinai and then taken to the Red Sea).[18] Also, it is considered unlikely that something as complicated as recessed panel architecture could have worked its way into Egypt by proxy, and at least a small contingent of migrants is often suspected.[17]

Despite this evidence of foreign influence, Egyptologists generally agree that the Gerzean Culture is predominantly indigenous to Egypt.

-

Decorated ware jar illustrating boats and trees; 3650–3500 BC; painted pottery; height: 16.2 cm, diameter: 12.9 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

Female figure; c. 3600 BC; terracotta; 29.2 × 14 × 5.7 cm; from Ma'mariya (Egypt); Brooklyn Museum (New York City)

-

Amulet in the form of a head of an elephant; 3500–3300 BC; serpentine (the green part) and bone (the eyes); 3.5 × 3.6 × 2.1 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

The Gebel el-Arak Knife; 3300–3200 BC; elephant ivory (the handle) and flint (the blade); length: 25.5 cm; most likely from Abydos (Egypt); Louvre

-

Jar with lug handles; c. 3500–3050 BC; diorite; height: 13 cm; Los Angeles County Museum of Art (US)

Protodynastic Period (Naqada III)

The Naqada III period, from about 3200 to 3000 BC,

Naqada III is notable for being the first era with

-

Squat vase with lug handles; 3050–2920 BC; porphyry; 11 × 20 cm; Los Angeles County Museum of Art (US)

-

The Davis comb; 3200–3100 BC; ivory; 5.5 × 3.9 × 0.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

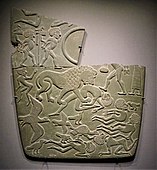

The Battlefield palette; 3100 BC; mudstone; width: 28.7 cm, depth: 1 cm; from Abydos (Egypt); British Museum (London)

-

Baboon Divinity bearing name of Pharaoh Narmer on its base; c. 3100 BC; calcite; height: 52 cm; Egyptian Museum of Berlin (Germany)

Art of Dynastic Egypt

Early Dynastic Period (3100–2685 BC)

The

Cosmetic palettes reached a new level of sophistication during this period, in which the Egyptian writing system also experienced further development. Initially, Egyptian writing was composed primarily of a few symbols denoting amounts of various substances. In the cosmetic palettes, symbols were used together with pictorial descriptions. By the end of the Third Dynasty, this had been expanded to include more than 200 symbols, both phonograms and ideograms.[20]

-

Both sides of theHierakonpolis (Egypt); Egyptian Museum (Cairo)

-

Tag depicting king Den; c. 3000 BC; ivory; 4.5 × 5.3 cm; from Abydos (Egypt); British Museum (London)[21]

-

Stela ofRaneb; c. 2880 BC; granite; height: 1 m, width: 41 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art(New York City)

-

Bracelet; c. 2650 BC; gold; diameter: 6 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Old Kingdom (2686–2181 BC)

The

-

Statue ofEgyptian Museum (Cairo). Demonstrates a group statue with Old Kingdom features and proportions.[23]

-

Statues of PrinceEgyptian museum at Cairo

-

louvre museum

-

Seated portrait statue of Dersenedj, scribe and administrator; circa 2400 BC; rose granite; height: 68 cm; from Giza; Egyptian Museum of Berlin

-

Seated portrait group of Dersenedj and his wife Nofretka; circa 2400 BC; rose granite; Egyptian Museum of Berlin

Middle Kingdom (c. 2055–1650 BC)

The Middle Kingdom of Egypt (a.k.a. "the Period of Reunification") is marked by political division known as the First Intermediate Period. The Middle Kingdom lasted from around 2050 BC to around 1710 BC, from the reunification of Egypt under the reign of Mentuhotep II of the Eleventh Dynasty to the end of the Twelfth Dynasty. The Eleventh Dynasty ruled from Thebes and the Twelfth Dynasty ruled from el-Lisht. During the Middle Kingdom period, Osiris became the most important deity in popular religion.[24] The Middle Kingdom was followed by the Second Intermediate Period of Egypt, another period of division that involved foreign invasions of the country by the Hyksos of West Asia.

After the reunification of Egypt in the Middle Kingdom, the kings of the Eleventh and Twelfth Dynasties were able to return their focus to art. In the Eleventh Dynasty, the king's monuments were made in a style influenced by the Memphite models of the Fifth and early Sixth Dynasties and the pre-unification Theban relief style all but disappeared. These changes had an ideological purpose, as the Eleventh Dynasty kings were establishing a centralized state, and returning to the political ideals of the Old Kingdom.[25] In the early Twelfth Dynasty, the artwork had a uniformity of style due to the influence of the royal workshops. It was at this point that the quality of artistic production for the elite members of society reached a high point that was never surpassed, although it was equaled during other periods.[26] Egypt's prosperity in the late Twelfth Dynasty was reflected in the quality of the materials used for royal and private monuments.

-

AnEgyptian Museum (Cairo)

-

Portrait head of an Egyptian from Thebes; circa 2000 BC; granite; Egyptian Museum of Berlin (Germany)

-

Coffin of Senbi; 1918–1859 BC; gessoed and painted cedar; overall: 70 x 55 cm; Cleveland Museum of Art

-

Jewelry chest of Sithathoryunet; 1887–1813 BC; ebony, ivory, gold, carnelian, blue faience and silver; height: 36.7 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Mirror with a papyrus-shaped handle; 1810–1700 BC; unalloyed copper, gold and ebony; 22.3 × 11.3 × 2.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Relief from the chapel of the overseer of the troops Sehetepibre; 1802–1640 BC; painted limestone; 30.5 × 42.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Lintel of Amenemhat I and deities; 1981–1952 BC; painted limestone; 36.8 × 172 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

A group of West Asiatic peoples (possibly Canaanites and precursors of the future Hyksos) depicted entering Egypt circa 1900 BC. From the tomb of a 12th dynasty official Khnumhotep II.[28][29][30][31]

Second Intermediate Period (c. 1650–1550 BC)

The

The so-called "

were found in Tanis and are associated with the Hyksos in the same manner.-

An official wearing the "mushroom-headed" hairstyle also seen in contemporary paintings of Western Asiatic foreigners such as in the tomb of Khnumhotep II, at Beni Hasan. Excavated in Avaris, the Hyksos capital. Staatliche Sammlung für Ägyptische Kunst.[40][41][42][43]

-

Lion inscribed with the name of the Hyksos ruler Khyan, found in Baghdad, suggesting relations with Babylon. The prenomen of Khyan and epithet appear on the breast. British Museum, EA 987.[44][45]

-

Apepi" and "Follower of his lord Nehemen", found at a burial at Saqqara.[46] Now at the Luxor Museum.[47][48]

-

An example of Egyptian Tell el-Yahudiyeh Ware, a Levantine-influenced style.

New Kingdom (c. 1550–1069 BC)

The

The artwork produced during the New Kingdom falls into three broad periods: Pre-Amarna, Amarna, and

Pre-Amarna

The Pre-Amarna period, the beginning of the eighteenth dynasty of the New Kingdom, was marked by the growing power of Egypt as an expansive empire. The artwork reflects a combination of Middle Kingdom techniques and subjects with the newly accessed materials and styles of foreign lands.[50] A large portion of the art and architecture of the Pre-Amarna period was produced by Queen Hatshepshut, who led a widespread building campaign to all gods during her reign from 1473 to 1458 B.C.E.. The queen made significant additions to the temple at Karnak, undertook the construction of an extensive mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri, and produced a prolific amount of statuary and relief work in hard stone. The extent of these building projects was made possible by the centralization of power in Thebes and reopening of trade routes by previous New Kingdom ruler Ahmose I.[51]

The Queen's elaborate mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri provides many well-preserved examples of the artwork produced during the Pre-Amarna period. The massive three-level, colonnaded temple was built into the cliffs of Thebes and adorned with extensive painted relief. Subjects of these reliefs ranged from traditional funerary images and legitimization of Hatshepsut as the divine ruler of Egypt to battle and expedition scenes in foreign lands. The temple also housed numerous statues of the Queen and gods, particularly Amun-ra, some of which were colossal in scale. The artwork from Hatshepshut's reign is trademarked by the re-integration of Northern culture and style as a result of the reunification of Egypt. Thutmoses III, the predecessor to the Queen, also commissioned vast amounts of large-scale artwork and by his death Egypt was the most powerful empire in the world.[51]

State-Sponsored Temples

During the New Kingdom – the 18th Dynasty especially – it was common for Kings to commission large and elaborate temples dedicated to the major gods of Egypt. These structures, built from limestone or sandstone (materials more permanent than the mud brick used for earlier temples) and filled with rare materials and vibrant wall paintings, exemplify the wealth and access to resources that Egyptian Empire enjoyed during the New Kingdom. The temple at Karnak, dedicated to Amun-ra, is one of the largest and best surviving examples of this type of state-sponsored architecture.[50]

-

Eye; 1550–1069 BC; alabaster eye from a coffin; length: 50.8 mm; Auckland War Memorial Museum (Auckland, New Zealand)

-

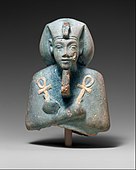

Ushabti of Amenhotep II; 1427–1400 BC; serpentine; 29 × 9 × 0.65 cm, 1.4 kg; British Museum (London)

-

Arm panel from a ceremonial chair of Thutmose IV; 1400–1390 BC; wood (ficus sycomorus?); height: 25.1 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

Gaming board inscribed for Amenhotep III with separate sliding drawer; 1390–1353 BC; glazed faience; 5.5 × 7.7 × 21 cm; Brooklyn Museum (New York City)

-

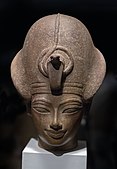

Head of Amenhotep III; 1390–1352 BC; quartzite; 24 × 20 cm, 9.8 kg; British Museum

-

Baboon figurine; 1390–1352 BC; quartzite; 68.5 × 38.5 × 45 cm, 180 kg (estimated); British Museum

-

Statuette of the lady Tiye; 1390–1349 BC; wood, carnelian, gold, glass, Egyptian blue and paint; height: 24 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

Abu Simbel, Temple of Ramesses II

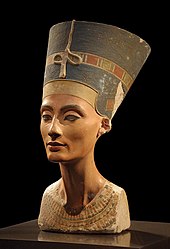

Amarna art (c. 1350 BC)

Amarna art is named for the extensive archeological site at Tel el-Amarna, where Pharaoh Akhenaten moved the capital in the late Eighteenth Dynasty. This period, and the years leading up to it, constitute the most drastic interruption in the style of Egyptian art in the Old, Middle, and New Kingdoms as a result of the rising prominence of the New Solar Theology and the eventual shift towards Atenism under Akhenaten.[54] Amarna art is characterized by a sense of movement and a "subjective and sensual perception" of reality as it appeared in the world. Scenes often include overlapping figures creating the sensation of a crowd, which was less common in earlier times.

The artwork produced under Akhenaten was a reflection of the dramatic changes in culture, style, and religion that occurred under Akhenaten's rule. Sometimes called the New Solar Theology, the

Portrayal of the human body shifted drastically under the reign of Akhenaten. For instance, many depictions of Akhenaten's body give him distinctly feminine qualities, such as large hips, prominent breasts, and a larger stomach and thighs. Facial representations of Akhenaten, such as in the sandstone Statue of Akhenaten, display him with an elongated chin, full lips, and hollow cheeks. These stylistic features extended past representations of Akhenaten and were further employed in the depiction of all figures of the royal family, as observed in the Portrait of Meritaten and Fragment of a queen's face. This is a divergence from the earlier Egyptian art which emphasized idealized youth and masculinity for male figures.

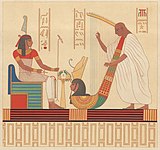

A notable innovation from the reign of Akhenaten was the religious elevation of the royal family, including Akhenaten's wife, Nefertiti, and their three daughters.[55] While earlier periods of Egyptian art depicted the king as the primary link between humanity and the gods, the Amarna period extended this power to those of the royal family.[55] As visualized in the relief of a royal family and the different talatat blocks, each figure of the royal family is touched by the rays of the Aten. Nefertiti specifically is believed to have held a significant cultic role during this period.[56]

Not many buildings from this period have survived, partially as they were constructed with standard-sized blocks, known as talatat, which were very easy to remove and reuse. Temples in Amarna, following the trend, did not follow traditional Egyptian customs and were open, without ceilings, and had no closing doors. In the generations after Akhenaten's death, artists reverted to the traditional Egyptian styles of earlier periods. There were still traces of this period's style in later art, but in most respects, Egyptian art, like Egyptian religion, resumed its usual characteristics as though the period had never happened. Amarna itself was abandoned and considerable effort was undertaken to deface monuments from the reign, including disassembling buildings and reusing the blocks with their decoration facing inwards, as has recently been discovered in one later building.[57] The last King of the Eighteenth Dynasty, Horemheb, sought to eliminate the influence of Amarna art and culture and reinstate the tradition powerful of the cult of Amun.[58]

-

Relief of the royal family: Akhenaten, Nefertiti and the three daughters; 1352–1336 BC; painted limestone; 25 × 20 cm; Egyptian Museum of Berlin (Germany)

-

Statue of Akhenaten; c. 1350 BC; painted sandstone; 1.3 × 0.8 × 0.6 m; Louvre

-

Talatat block with Akhenaton standing to the right, raising his hands in prayer to the rays of the sun god Aten; circa 1350 BC; painted sandstone; from Karnak; Egyptian Museum of Berlin

-

Shabti of Akhenaten; 1353–1336 BC; faience; height: 11 cm, width: 7.6 cm, depth: 5.2 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art(New York City)

-

Fragment of a queen's face; 1353–1336 BC; yellow jasper; height: 13 cm, width: 12.5 cm, depth: 12.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Cosmetic dish in the shape of a trussed duck; 1353-1327 BC; hippopotamus ivory (tinted); duck (left), length: 9.5 cm, width: 4.6 cm; cover (right), length: 7.3 cm, width: 4 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Ramesside Period

With a concerted effort from Horemheb, the last King of Dynasty Eighteen, to eradicate all Amarna art and influence, the style of the art and architecture of the Empire transitioned into the Ramesside Period for the remainder of the New Kingdom (

During the Ramesside period kings made further contributions to the Temple at Karnak. The Great Hypostyle Hall, commissioned by Sety I (19th Dynasty), consisted of 134 sandstone columns supporting a 20-meter-high ceiling, and covering an acre of land. Sety I decorated most surfaces with intricate bas-relief while his successor, Ramses II added sunken relief work to the walls and columns in the southern side of the Great Hall. The interior carvings show king-god interactions, such as traditional legitimization of power scenes, processions, and rituals. Expansive depictions of military campaigns cover the exterior walls of Hypostyle Hall. Battle scenes illustrating chaotic, disordered enemies strewn over the conquered land and the victorious king as the most prominent figure, trademark the Ramesside period.[50]

The last period of the New Kingdom demonstrates a return to traditional Egyptian form and style, but the culture is not purely a reversion to the past. The art of the Ramesside period demonstrates the integration of canonized Egypt forms with modern innovations and materials. Advancements such as adorning all surfaces of tombs with paintings and relief and the addition of new funerary texts to burial chambers demonstrate the non-static nature of this period.[50]

Third Intermediate Period (c.1069–664 BC)

The Third Intermediate Period was one of decline and political instability, coinciding with the

The Third Intermediate Period generally sees a return to archaic Egyptian styles, with particular reference to the art of the

Late Period (c. 664–332 BC)

In 525 BC, the political state of Egypt was taken over by the Persians, almost a century and a half into Egypt's Late Period. By 404 BC, the Persians were expelled from Egypt, starting a short period of independence. These 60 years of Egyptian rule were marked by an abundance of usurpers and short reigns. The Egyptians were then reoccupied by the Achaemenids until 332 BC with the arrival of Alexander the Great. Sources state that the Egyptians were cheering when Alexander entered the capital since he drove out the immensely disliked Persians. The Late Period is marked with the death of Alexander the Great and the start of the Ptolemaic dynasty.[66] Although this period marks political turbulence and immense change for Egypt, its art and culture continued to flourish.

This can be seen in Egyptian temples starting with the

Another relief originating from the Thirtieth Dynasty was the rounded modeling of the body and limbs,[66] which gave the subjects a more fleshy or heavy effect. For example, for female figures, their breasts would swell and overlap the upper arm in painting. In more realistic portrayals, men would be fat or wrinkled.

Another type of art that became increasingly common during this period was the Horus stelae.[66] These originate from the late New Kingdom and intermediate period but were increasingly common during the fourth century to the Ptolemaic era. These statues would often depict a young Horus holding snakes and standing on some kind of dangerous beast. The depiction of Horus comes from the Egyptian myth where a young Horus is saved from a scorpion bite, resulting in his gaining power over all dangerous animals. These statues were used "to ward off attacks from harmful creatures, and to cure snake bites and scorpion stings".[66]

-

Composite papyrus capital; 380–343 BC; painted sandstone; height: 126 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

Magical stela or cippus of Horus; 332–280 BC; chlorite schist; height: 20.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Relief showing , Egypt)

Ptolemaic Period (305–30 BC)

Discoveries made since the end of the 19th century surrounding the (now submerged) ancient Egyptian city of Heracleion at Alexandria include a 4th century BC, unusually sensual, detailed and feministic (as opposed to deified) depiction of Isis, marking a combination of Egyptian and Hellenistic forms beginning around the time of Egypt's conquest by Alexander the Great in 332–331 BC. However, this was atypical of Ptolemaic sculpture, which generally avoided mixing Egyptian styles with the Hellenistic style used in the court art of the Ptolemaic dynasty,[68] while temples in the rest of the country continued using late versions of traditional Egyptian formulae.[69] Scholars have proposed an "Alexandrian style" in Hellenistic sculpture, but there is in fact little to connect it with Alexandria.[70]

In the 2nd century, Egyptian temple sculptures began to reuse court models in their faces, and sculptures of a priest often used a Hellenistic style to achieve individually distinctive portrait heads.[75] Many small statuettes were produced, with the most common types being Alexander, a generalized "King Ptolemy", and a naked Aphrodite. Pottery figurines included grotesques and fashionable ladies of the Tanagra figurine style.[69] Erotic groups featured absurdly large phalli. Some fittings for wooden interiors include very delicately patterned polychrome falcons in faience.

-

Ptolemy XII making offerings to Egyptian Gods, in the Temple of Hathor, 54 BC, Dendera, Egypt

-

Double-sided votive relief; c. 305 BC; limestone; 8.3 × 6.5 × 1.4 cm; Cleveland Museum of Art (Cleveland, Ohio, US)

-

Statue of the goddess Raet-Tawy; 332–30 BC; limestone; 46 × 13.7 × 23.7 cm; Louvre

-

Ibis coffin; 305–30 BC; wood, silver, gold, and rock crystal; 38.2 × 20.2 × 55.8 cm; Brooklyn Museum (New York City)

-

Statue of a Ptolemaic king; 1st century BC; basalt; height: 82 cm, width: 39.5 cm; Louvre

Roman Period (30 BC–619 AD)

Mummy portraits have been found across

The portraits date to the Imperial Roman era, from the late 1st century BC or the early 1st century AD onwards. It is not clear when their production ended, but recent research suggests the middle of the 3rd century. They are among the largest groups among the very few survivors of the panel painting tradition of the classical world, which was continued into Byzantine and Western traditions in the post-classical world, including the local tradition of Coptic iconography in Egypt.

-

The Fayum mummy portraits epitomize the meeting of Egyptian and Roman cultures.

-

Mummy mask of a man; early 1st century AD; stucco, gilded and painted; 51.5 x 33 x 20 cm; Brooklyn Museum (New York City)

-

Portrait of a young woman in red; c. 90–120 ; encaustic painting on limewood with gold leaf; height: 38 cm (15 in); Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

Statue of Anubis; 100–138; marble; height: 1.5 m, width: 50 cm; from Tivoli (Rome); Vatican Museums (Vatican City)[79]

-

Mummy portrait of a man; late 1st century; encaustic painting on wood; Walters Art Museum (Baltimore, Maryland, US)

-

Isis suckling her baby Horus (of whom only the left leg is preserved); 1st century AD; siltstone (basis: limestone); height: 33.9 cm; from Mata´na el-Asfu; Staatliche Sammlung für Ägyptische Kunst (Munich, Germany)

Characteristics

Egyptian art is known for its distinctive figure convention used for the main figures in both

Anonymity

Ancient Egyptian artists rarely left their names. The Egyptian artwork is anonymous also because most of the time it was collective. Diodorus of Sicily, who traveled and lived in Egypt, has written: "So, after the craftsmen have decided the height of the statue, they all go home to make the parts which they have chosen" (I, 98).[86]

Symbolism

Symbolism pervaded Egyptian art and played an important role in establishing a sense of order. The pharaoh's regalia, for example, represented his power to maintain order. Animals were also highly symbolic figures in Egyptian art. Some colors were expressive.[87]

The

This color symbolism explains the popularity of turquoise and faience in funerary equipment. The use of black for royal figures similarly expressed the fertile alluvial soil[87] of the Nile from which Egypt was born, and carried connotations of fertility and regeneration. Hence statues of the king as Osiris often showed him with black skin. Black was also associated with the afterlife, and was the color of funerary deities such as Anubis.

Gold indicated divinity due to its unnatural appearance and association with precious materials.[87] Furthermore, gold was regarded by the ancient Egyptians as "the flesh of the god".[90] Silver, referred to as "white gold" by the Egyptians, was likewise called "the bones of the god".[90]

Red, orange and yellow were ambivalent colors. They were, naturally, associated with the sun; red stones such as quartzite were favored for royal statues which stressed the solar aspects of kingship. Carnelian has similar symbolic associations in jewelry. Red ink was used to write important names on papyrus documents. Red was also the color of the deserts, and hence associated with Set.

Materials

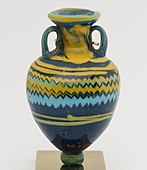

Faience

Egyptian faience is a ceramic material, made of quartz sand (or crushed quartz), small amounts of lime, and plant ash or natron. The ingredients were mixed together, glazed and fired to a hard shiny finish. Faience was widely used from the Predynastic Period until Islamic times for inlays and small objects, especially ushabtis. More accurately termed 'glazed composition', Egyptian faience was so named by early Egyptologists after its superficial resemblance to the tin-glazed earthenwares of medieval Italy (originally produced at Faenza). The Egyptian word for it was tjehenet, which means 'dazzling', and it was probably used, above all, as a cheap substitute for more precious materials like turquoise and lapis lazuli. Indeed, faience was most commonly produced in shades of blue-green, although a large range of colours was possible.[91]

-

William the Faience Hippopotamus; 1961–1878 BC; faience; 11.2 × 7.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

Bowl; 200–150 BC; faience; 4.8 × 16.9 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Glass

Although the glassy materials faience and

-

Kohl vase in the shape of a palm column; 1550–1086 BC; glass; height: 8.9 cm; Walters Art Museum (Baltimore, US)

-

Bottle; 1353–1336 BC; glass; height: 8.1 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

Bottle; 1295–1070 BC; glass; height: 10 cm (4 in); Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Small amphoriskos; 664–332 BC; glass; height: 7 cm (2.8 in); Metropolitan Museum of Art

Egyptian blue

Egyptian blue is a material related to, but distinct from, faience and glass. Also called "frit", Egyptian blue was made from

The color blue was used only sparingly even up until as late as Dynasty IV, where the color was found adorning mat-patterns in the Tomb of Saccara, which was constructed during the first Dynasty. Until this discovery was made, the color blue had not been known in Egyptian art.[94]

-

Powder of Egyptian blue

-

Amphora, an example of so-called "Egyptian blue" ceramic ware; 1380–1300 BC; height: 12.6 cm (4.9 in); Walters Art Museum (Baltimore, US)

Metals

While not a leading center of metallurgy, ancient Egypt nevertheless developed technologies for extracting and processing the metals found within its borders and in neighbouring lands.

Copper was the first metal to be exploited in Egypt. Small beads have been found in

The golden treasure of

Silver had to be imported from the

Iron was the last metal to be exploited on a large scale by the Egyptians. Meteoritic iron was used for the manufacture of beads from the Badarian period. However, the advanced technology required to smelt iron was not introduced into Egypt until the Late Period. Before that, iron objects were imported and were consequently highly valued for their rarity. The

-

Amun-Ra figurine; 1069–664 BC; silver and gold; 24 × 6 × 8.5 cm, 0.7 kg; British Museum (London)

-

Statuette of Amun; 945–715 BC; gold; 17.5 × 4.7 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

Figurine of Horus as falcon god with an Egyptian crown; circa 500 BC; silver and electrum; height: 26.9 cm; Staatliche Sammlung für Ägyptische Kunst (Munich, Germany)

-

Statuette of Isis and Horus; 305–30 BC; solid cast of bronze; 4.8 × 10.3 cm; Cleveland Museum of Art (Cleveland, Ohio, US)

Wood

Because of its relatively poor survival in archaeological contexts, wood is not particularly well represented among artifacts from Ancient Egypt. Nevertheless, woodworking was evidently carried out to a high standard from an early period. Native trees included

-

Model of a procession of offering bearers. Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

Figurine of a female servant carrying provisions; 1981–1975 BC; painted wood and gesso; 112 × 17 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

Model of a sailboat; 1981–1975 BC; painted wood, plaster, linen twine and linen fabric; length: 145 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Duck-shaped box; 16th–11th century BC; wood and ivory; Louvre

-

Figurine of Isis; Ptolemaic dynasty; painted wood and stucco; height: 40.5 cm; Roemer- und Pelizaeus-Museum Hildesheim (Hildesheim, Germany)

Lapis lazuli

Lapis lazuli is a dark blue semi-precious stone highly valued by the ancient Egyptians because of its symbolic association with the heavens. It was imported via long-distance trade routes from the mountains of north-eastern Afghanistan, and was considered superior to all other materials except gold and silver. Coloured glass or faience provided a cheap imitation. Lapis lazuli is first attested in the Predynastic Period. A temporary interruption in supply during the Second and Third Dynasties probably reflects political changes in the ancient Near East. Thereafter, it was used extensively for jewelry, small figurines and amulets.[97]

-

Scarab finger ring; 1850–1750 BC; diameter: 2.5 cm, the scarab: 1.8 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

Cult image of Ptah; 945–600 BC; height of the figure: 5.2 cm, height of the dais: 0.4 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Falcom amulet; 664–332 BC; height: 2.2 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Child god (Harpokrates?) amulet; 664–30 BC; height: 4.3 cm, width: 1.2 cm, depth: 1.6 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Other materials

- Jasper is an impure form of chalcedony with bands or patches of red, green or yellow. Red jasper, symbol of life and of positive aspects of the universe, was used above all to make amulets. It was ideal for certain amulets, such as the tit amulet, or tyet (also known as knot of Isis), to be made of red jasper, as specified in Spell 156 of the Book of the Dead. The more rarely used green jasper was especially indicated for making scarabs, particularly heart scarabs.

- Serpentine is the generic term for the hydrated silicates of magnesium. It came mostly from the eastern desert, and occurs in many shades of color, from a pale green to a dark verging on black. Used from the earliest times, it was sought specially for making heart scarabs.

- Predynastic Periodon, although in subsequent periods it was usually covered in a fine layer of faience and was used in the manufacture of numerous scarabs.

- Late Period, turquoise (like lapis lazuli) was synonymous with joy and delight.

-

Pendant; circa 1069 BC; gold and turquoise; overall: 5.1 x 2.3 cm; Cleveland Museum of Art (Cleveland, USA)

-

Heart scarab of Hatnefer; 1492–1473 BC; serpentine (the scarab) and gold; 5.3 × 2.8 cm; chain: 77.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Head from a spoon in the form of a swimming girl; 1390–1353 BC; travertine (the head) and steatite (the hair); 2.8 × 2.7 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Amulet; 1295–1070 BC; red jasper; 2.3 × 1.2 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Sculpture

The

Egyptian

By Dynasty IV (2680–2565 BC), the idea of the

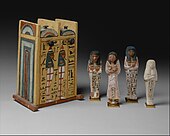

Early tombs also contained small models of the slaves, animals, buildings and objects such as boats (and later ushabti figures) necessary for the deceased to continue his lifestyle in the afterlife.[100] However, the great majority of wooden sculpture have been lost to decay, or probably used as fuel. Small figures of deities, or their animal personifications, are very common, and found in popular materials such as pottery. There were also large numbers of small carved objects, from figures of the gods to toys and carved utensils. Alabaster was used for expensive versions of these, though painted wood was the most common material, and was normal for the small models of animals, slaves and possessions placed in tombs to provide for the afterlife.

Very strict conventions were followed while crafting statues, and specific rules governed the appearance of every Egyptian god. For example, the sky god (Horus) was to be represented with a falcon's head, the god of funeral rites (Anubis) was to be shown with a jackal's head. Artistic works were ranked according to their compliance with these conventions, and the conventions were followed so strictly that, over three thousand years, the appearance of statues changed very little. These conventions were intended to convey the timeless and non-ageing quality of the figure's ka.[citation needed]

A common relief in ancient Egyptian sculpture was the difference between the representation of men and women. Women were often represented in an idealistic form, young and pretty, and rarely shown in an older maturity. Men were shown in either an idealistic manner or a more realistic depiction.[49] Sculptures of men often showed men that aged, since the regeneration of ageing was a positive thing for them whereas women are shown as perpetually young.[101]

-

Both sides of theHierakonpolis (Egypt); Egyptian Museum (Cairo). This very old palette shows the canonical Egyptian profile view and proportions of the figure

-

Portrait statue of Henka, administrator of the two pyramids of pharaohSnofru; 2500–2350 BC; limestone; height: 40 cm; Egyptian Museum of Berlin(Germany)

-

The Ka statue of Awibre Hor, which provided a physical place for the ka to manifest; c. 1700 BC; wood, rock crystal, quartz, plaster, traces of gold; height: 1.7 m; from Dahshur; Egyptian Museum (Cairo)

-

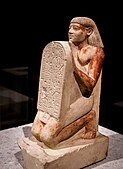

Kneeling portrait statue of Amenemhat holding a stele with an inscription; circa 1500 BC; limestone; Egyptian Museum of Berlin

-

Portrait head of pharaoh Hatshepsut or Thutmose III; 1480–1425 BC; most probably granite; height: 16.5 cm; Egyptian Museum of Berlin

-

Portrait statuette of Taitai; 1380–1300 BC; greywacke; height: height: 27.5 cm; Egyptian Museum of Berlin

-

The Anubis Shrine; 1336–1327 BC; painted wood and gold; 1.1 × 2.7 × 0.52 m; from the Valley of the Kings; Egyptian Museum (Cairo)

-

Osiris on a lapis lazuli pillar in the middle, flanked by Horus on the left, and Isis on the right; 875–850 BC; gold and lapis lazuli; 9 cm; Louvre

-

Four cats; 664–332 BC; wood; height: 14 cm, width: 27 cm; Louvre

-

Statuette of Anubis; 332–30 BC; plastered and painted wood; 42.3 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

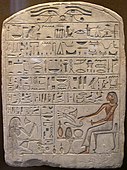

Stele

A stele is an upright tablet of stone or wood, often with a curved top, painted and carved with text and pictures. Numerous examples were produced throughout Egyptian history for a variety of purposes, including funerary, votive and commemorative. Funerary stelae, attested from the early 1st Dynasty, typically bore the name and titles of the deceased. This basic form, which served to identify the tomb owner, evolved into a key component of the funerary equipment with a magical function. Hence, from the 2nd Dynasty onward, the owner was usually shown seated before an offering table piled with food and drink; in the Middle Kingdom, the offering formula was generally inscribed along the top of the stele. Both were designed to ensure a perpetual supply of offerings in the afterlife. Votive stelae, inscribed with prayers to deities, were dedicated by worshipers seeking a favorable outcome to a particular situation. In the Middle Kingdom, many hundreds were set up by pilgrims on the "terrace of the great god" at Abydos, so that they might participate in the annual procession of Osiris. One particular variety of votive stele common in the New Kingdom was the ear stele, inscribed with images of human ears to encourage the deity to listen to the prayer or request.

Commemorative stelae were produced to proclaim notable achievements (for example, the stela of

-

Kamose stela; circa 1550 BC; limestone; height: 2.3 m, width: 1.1 m, depth: 28.5 cm; from the Karnak Temple (Egypt); Luxor Museum (Luxor, Egypt)[104]

-

Stela ofSankt Petersburg, Russia)

-

Stela of Nacht-Mahes-eru; 664–610 BC; polychromy on wood; 42 × 31.5 × 3.5 cm;National Museum in Warsaw(Poland)

Pyramidia

A pyramidion is a capstone at the top of a pyramid. Called benbenet in

-

Fragment of a pyramidion; c. 1600 BC; from Thebes; British Museum (London)

-

Pyramidion from the pyramid of Nebamun; circa 1380 BC; painted limestone; height: 23 cm; Staatliche Sammlung für Ägyptische Kunst (Munich, Germany)

-

Pyramidion from the tomb of the priest Rer in Abydos, Egypt. Hermitage Museum

-

Pyramidion of Iufaa; 664–525 BC; painted limestone; height: 36 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Painting

Not all Egyptian

Many ancient Egyptian paintings have survived in tombs, and sometimes temples, due to Egypt's extremely dry climate. The paintings were often made with the intent of making a pleasant afterlife for the deceased. The themes included journeys through the afterworld or protective deities introducing the deceased to the gods of the underworld (such as Osiris). Some tomb paintings show activities that the deceased were involved in when they were alive and wished to carry on doing for eternity.[citation needed]

From the New Kingdom period and afterwards, the Book of the Dead was buried with the entombed person. It was considered important for an introduction to the afterlife.[107]

Egyptian paintings are painted in such a way to show a side view and a front view of the animal or person at the same time. For example, the painting to the right shows the head from a profile view and the body from a frontal view. Their main colors were red, blue, green, gold, black and yellow.[citation needed]

Paintings showing scenes of hunting and fishing can have lively close-up landscape backgrounds of reeds and water, but in general Egyptian painting did not develop a sense of depth, and neither landscapes nor a sense of visual perspective are found, the figures rather varying in size with their importance rather than their location.[citation needed]

-

Block from a relief depicting a battle; 1427–1400 BC; painted sandstone; height: 61.5 cm (24.2 in); Metropolitan Museum of Art (US)

-

Fresco which depicts Nebamun hunting birds; 1350 BC; paint on plaster; 98 × 83 cm (3 ft 2.5 in × 2 ft 8.7 in); British Museum (London)

-

Fresco which depicts the pool in Nebamun's estate garden; c. 1350 BC; painted plaster; height: 64 cm; British Museum

-

Frescos in theTomb of Nefertari, in which appear Kheprisitting on a very colourful square-shaped throne

-

Wall painting fromTutankhamun's tomb depicting Ayperforming the Opening of the Mouth ceremony

-

Scene from the tomb of Tutankhamun in which appears Osiris

-

The Book of the Dead of Hunefer; c. 1275 BC; ink and pigments on papyrus; 45 × 90.5 cm; British Museum (London)

Architecture

Ancient Egyptian architects used sun-dried and kiln-baked bricks, fine sandstone, limestone and granite. Architects carefully planned all their work. The stones had to fit precisely together, since no mud or mortar was used. When creating the pyramids it is unknown how the workers or stones reached the top of them as no records were kept of their construction. When the top of the structure was completed, the artists decorated from the top down, removing ramp sand as they went down. Exterior walls of structures like the pyramids contained only a few small openings. Hieroglyphic and pictorial carvings in brilliant colors were abundantly used to decorate Egyptian structures, including many motifs, like the scarab, sacred beetle, the solar disk, and the vulture. They described the changes the Pharaoh would go through to become a god.[109]

As early as 2600 BC the architect Imhotep made use of stone columns whose surface was carved to reflect the organic form of bundled reeds, like papyrus, lotus and palm; in later Egyptian architecture faceted cylinders were also common. Their form is thought to derive from archaic reed-built shrines. Carved from stone, the columns were highly decorated with carved and painted hieroglyphs, texts, ritual imagery and natural motifs. One of the most important types are the papyriform columns. The origin of these columns goes back to the

-

Pair of obelisks of Nebsen; 2323–2100 BC; limestone; (the one from left) height: 52.7 cm, (the one from right) height: 51.1 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

Model of a house; 1750–1700 BC; pottery; 27 x 27 x 17 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Ceiling painting from the palace of Amenhotep III; circa 1390–1353 BC; dried mud, mud plaster and paint Gesso; 140 x 140 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Window grill from a palace of Ramesses III; 1184–1153 BC; painted sandstone; height: 103.5 cm, width: 102.9 cm, depth: 14.6 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Column with Hathor-emblem capital and names of Nectanebo I on the shaft; 380–362 BC; limestone; height: 102 cm, width: 34.3 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

The Temple of Dendur; completed by 10 BC; aeolian sandstone; temple proper: height: 6.4 m, width: 6.4 m; length: 12.5 m; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

A view of the pyramids at Giza. From left to right, the three largest are: theGreat Pyramid of Khufu

-

The well preserved Temple of Isis fromPhilae (Egypt) is an example of Egyptian architecture and architectural sculpture

-

TheGreat Temple of Ramesses II from Abu Simbel, founded in circa 1264 BC, in the Aswan Governorate(Egypt)

-

Relief from the Dendera Temple complex (Egypt)

-

Illustrations of various types of capitals, drawn by the Egyptologist Karl Richard Lepsius

-

Illustrations with two types of columns from the hall of theRamses IITemple, drawn in 1849

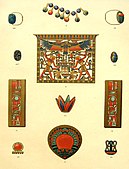

Jewelry

The ancient Egyptians exhibited a love of ornament and personal decoration from earliest

The particular choice of materials depended upon practical, aesthetical and symbolic considerations. Some types of jewelry remained perennially popular, while others went in and out of fashion. In the first category were bead necklaces, bracelets, armlets and girdles. Bead aprons are first attested in the 1st Dynasty, while

The techniques of jewelry-making can be reconstructed from surviving artifacts and from tomb decoration. A jeweler's workshop is shown in the tomb of Mereruka; several New Kingdom tombs at Thebes contain similar scenes.[110]

-

Broad collar of Wah; 1981–1975 BC; faience and linen thread; height: 34.5 cm, width: 39 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

Pectoral and necklace of Princess Sithathoriunet; 1887–1813 BC; gold, carnelian, lapis lazuli, turquoise, garnet & feldspar; height of the pectoral: 4.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Broad collar of Senebtisi; 1850–1775 BC; faience, gold, carnelian and turquoise; outside diameter: 25 cm, maxim width: 7.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Pectoral (chest jewellery) of Tutankhamun; 1336–1327 BC (Reign of Tutankhamun); gold, silver and meteoric glass; height: 14.9 cm; Egyptian Museum (Cairo)

-

Pectoral of Horus with sundisk; circa 1325 BC; gold with gemstones; width: 12.6 cm; Egyptian Museum (Cairo)

-

Signet ring; 664–525 BC; gold; diameter 3 cm, length: 3.4 cm (bezel); British Museum (London)

-

1849 illustrations of the Ferlini Treasures, discovered in 1830 by the Italian explorer, Giuseppe Ferlini; in the New York Public Library

-

Illustration of jewelry from the tomb of princess Merit

Amulets

An amulet is a small charm worn to afford its owner magical protection, or to convey certain qualities (for example, a lion amulet might convey strength, or a set-square amulet might convey rectitude). Attested from the

-

Amulet that depicts Thoth as a baboon holding the Eye of Horus; 664–332 BC; Egyptian faience with light green glaze; height: 3.9 cm, width: 2.4 cm, depth: 2.5 cm; Walters Art Museum (Baltimore, US)

-

Amulet which depicts a triad of Isis, Horus and Nephthys; 664–332 BC; faience; height: 4.5 cm, width: 3 cm, depth: 2.2 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

Amulet depicting Taweret; 664–332 BC; faience; height: 9.7 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Scarab-shaped amulets

The protective amulet for the heart was in the form of the scarab beetle, the manifestation of the creator and solar deity Khepri. It was a symbol of new life and resurrection. The scarab beetle was seen to push a ball of dung along the ground, and from this came the idea of the beetle rolling the sun across the sky. Subsequently, the young beetles were observed to hatch from their eggs inside the ball, hence the idea of creation: life springs forth from primordial mud.

The heart scarab was a large scarab amulet which was wrapped in the mummy bandaging over the deceased's heart. It was made from a range of green and dark-colored materials, including faience, glass, glazed

-

Heart scarab of the singer of Amun Iakai; 1550–1186 BC; glass; length: 4.8 cm, width: 3.5 cm, height: 1.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

The back of a heart scarab of the singer of Amun Iakai; 1550–1186 BC; glass; length: 4.8 cm, width: 3.5 cm, height: 1.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Commemorative scarab of Amenhotep III, recording a lion hunt; 1390–1352 BC; blue-glazed steatite; length: 8 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

The back of a commemorative scarab of Amenhotep III, recording a lion hunt; 1390–1352 BC; blue glazed steatite; length: 8 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

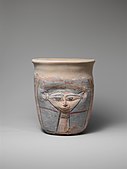

Pottery

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2019) |

Different types of pottery items were deposited in tombs of the dead. Some such pottery items represented interior parts of the body, such as the

-

Blue-painted jar from Malqata; 1390–1353 BC; painted pottery; height: 69 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

Hathor-shaped jar; 1390–1353 BC; painted pottery; height: 24.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Cup ornated with papyrus flowers; 653–640 BC; terracotta; Louvre

-

Goblet ornated with uraeuses; 653–640 BC; terracotta; Louvre

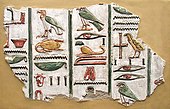

Calligraphy

Egyptian writing remained a remarkably conservative system, and the preserve of a tiny literate minority, while the spoken language underwent considerable change. Egyptian stelas are decorated with finely carved hieroglyphs.

The use of hieroglyphic writing arose from

-

Relief with hieroglyphs from theEdfu Temple (Edfu, Egypt)

-

Hieroglyphs on the Stele Minnakht from c. 1321 BC, in the Louvre

-

Detail from the side of a sarcophagus, circa 530 BC, in the British Museum (London)

-

Hieroglyphs from the tomb of Seti I

Furniture

Although, by modern standards, ancient Egyptian houses would have been very sparsely furnished, woodworking and cabinet-making were highly developed crafts. All the main types of furniture are attested, either as surviving examples or in tomb decoration. Chairs were only for the wealthy; most people would have used low stools. Beds consisted of a wooden frame, with matting or leather webbing to provide support; the most elaborate beds also had a canopy, hung with netting, to provide extra privacy and protection from insects. The feet of chairs, stools and beds were often modeled to resemble bull hooves or, in later periods, lion feet or duck heads. Wooden furniture was often coated with a layer of plaster and painted.

Royal furniture was more elaborate, making use of inlays, veneers and marquetry. Funerary objects from the

-

Furniture leg in shape of bull's leg; 2960–2770 BC; hippopotamus ivory; height: 17 cm, width: 3.4 cm, depth: 5.8 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

Stool with woven seat; 1991–1450 BC; wood & reed; height: 13 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Inlaid box for cosmetic vessels of Sithathoryunet; 1887–1813 BC; ebony, inlaid with ivory and red wood (restored) and gold trim; height: 25.2 cm, length: 36.4 cm, depth: 25.2 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Headrest; 1539–1190 BC; wood; 17.8 x 28.6 x 7.6 cm; Brooklyn Museum (New York City)

-

Chair ofHatnefer; 1492–1473 BC; boxwood, cypress, ebony & linen cord; height: 53 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Chair of Reniseneb; 1450 BC; wood, ebony & ivory; height: 86.2 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

The Throne ofsemi-precious and other stones, faience, glass and bronze; height: 1 m; Egyptian Museum(Cairo)

-

Armchair of Tutankhamun; 1336–1326 BC; wood, ebony, ivory and gold leaf; height: 71 cm; Exposition of Tutankhamun Treasure in Paris (2019)

Clothing

Artistic representations, supplemented by surviving garments, are the main sources of evidence for ancient Egyptian fashion. The two sources are not always in agreement, however, and it seems that representations were more concerned with highlighting certain attributes of the person depicted than with accurately recordings their true appearance. For example, women were often shown with restrictive, tight-fitting dresses, perhaps to emphasize their figures.

As in most societies, fashions in Egypt changed over time; different clothes were worn in different seasons of the year, and by different sections of society. Particular office-holders, especially priests and the king, had their own special garments.

For the general population, clothing was simple, predominantly of linen, and probably white or off-white in color. It would have shown the dirt easily, and professional launderers are known to have been attached to the New Kingdom workmen's village at Deir el-Medina. Men would have worn a simple loin-cloth or short kilt (known as shendyt), supplemented in winter by a heavier tunic. High-status individuals could express their status through their clothing, and were more susceptible to changes in fashion.

Longer, more voluminous clothing made an appearance in the

-

Pair of sandals; 1390–1352 BC; grass, reed and papyrus; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

Illustration from the book Ancient Egyptian, Assyrian, and Persian costumes and decorations

-

Illustration of a goddess from Ancient Egyptian, Assyrian, and Persian costumes and decorations

-

Statue of Tjahapimu wearing a shendyt, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Cosmetics

Use of makeup, especially around the eyes, was a characteristic feature of ancient Egyptian culture from Predynastic times. Black kohl (eye-paint) was applied to protect the eyes, as well as for aesthetic reasons. It was usually made of galena, giving a silvery-black color; during the Old Kingdom, green eye-paint was also used, made from malachite. Egyptian women painted their lips and cheeks, using rouge made from red ochre. Henna was applied as a dye for hair, fingernails and toenails, and perhaps also nipples. Creams and unguents to condition the skin were popular, and were made from various plant extracts.[117]

-

Cosmetic Box of the Royal Butler Kemeni; 1814–1805 BC;cedar with ebony, ivory veneer and silver mounting; height: 20.3 cm (8 in); Metropolitan Museum of Art(New York City)

-

Cosmetic dish in the shape of a tilapia fish; 1479–1425 BC; glazed steatite; 8.6 × 18.1 cm (3.4 × 7.1 in); Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Cosmetic box in the shape of an Egyptian composite capital, its cap being in the left side; 664–300 BC; glassy faience; 8.5 × 9 cm (3.4 × 3.5 in); Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Perfume vase in shape of an amphoriskos; 664–630 BC; glass: 8 × 4 cm (3.1 × 1.5 in); Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

An 18th Dynasty ancient Egyptian kohl container inscribed for Queen Tiye (1410–1372 BC)

Music

On secular and religious occasions, music played an important part in celebrations. Musicians, playing instruments such as the castanets and flute, are depicted on objects from the

-

A blind harpist from a mural of the 15th century BC

-

Arched Harp (shoulder harp); 1390–1295 BC; wood; length of sound box: 36 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

Head of Hathor from a clapper; 1295–664 BC; possibly boxwood; 12 × 6.2 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Detail of a frieze from TT52 in which are depicted three musicians

-

Illustration of a harper playing in front of god Shu

Sistrum

A sistrum (plural: sistra) is a rattle used in religious ceremonies, especially temple rituals, and usually played by women. Called a "seshsehet" in Egyptian, the name imitates the swishing sound the small metal disks made when the instrument was shaken. It was closely associated with Hathor in her role as "lady of music", and the handle was often decorated with a Hathor head. Two kinds of sistrum are attested, naos-shaped and hoop-shaped; the latter became the more common.[119]

-

Sistrum decorated with a Hathor face; 664–332 BC; faience; length: 15.5 cm, width: 6.4 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

Sistrum inscribed with the name ofPtolemy I; 305–282 BC; faience; 26.7 × 7.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Sistrum with the face of the goddess Hathor depicted with cow ears; 380–250 BC; bronze; 36.3 cm; Walters Art Museum (Baltimore, US)

-

1st–2nd century AD; bronze or copper alloy; 20.6 × 14 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Funerary art

Coffins

The earliest purpose-built funerary containers for bodies were simple rectangular wooden boxes, attested in the 1st Dynasty. A coffin swiftly became an essential part of the burial equipment. Known euphemistically as the "lord of life", its primary function was to provide a home for the Ka and to protect the physical body from harm. In the 4th Dynasty, the development of longer coffins allowed the body to be buried fully extended (rather than curled up on its side in a foetal position). At the end of the Old Kingdom, it became customary once more for the body to be laid on its side. The side of the coffin that faced east in the tomb was decorated with a pair of eyes so that the deceased could look out towards the rising sun with its promise of daily rebirth. Coffins also began to be decorated on the outside with bands of funerary texts, while pictures of food and drink offerings were painted on the inside to provide a magical substitute for the real provisions placed in the tomb.[citation needed]

In the

Coffins were generally made of wood; those of high-status individuals used fine quality, imported

-

Coffin of the estate manager Khnumhotep; 1981–1802 BC; painted wood (ficus sycomorus); height: 81.3 cm (32 in); Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

Coffin of Nesykhonsu; c. 976 BC; gessoed and painted sycamore fig; overall: 70 cm; Cleveland Museum of Art (Cleveland, Ohio, US)

-

Inner coffin ofAmenemopet; 975–909 BC; painted wood & gesso; length: 195 cm (77 in); Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Coffin of Irtirutja; 332–250 BC; plastered, painted and gilded wood; length: 198.8 cm (78.3 in); Metropolitan Museum of Art

Canopic jars

Canopic jars are vessels which were used for storing the internal organs removed during mummification. These were named after the human-headed jars that were worshiped as personifications of Kanops (the helmsman of

-

Canopic jars of Ruiu; 1504–1447 BC; painted pottery; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

Canopic jars of Tutankhamun; 1333–1323 BC; alabaster; total height: 85.5 cm; Egyptian Museum (Cairo)

-

Complete set of canopic jars; 900–800 BC; painted limestone; Walters Art Museum (Baltimore, US)

-

Complete set of canopic jars decorated withhieroglyphics; 744–656 BC; painted sycomore fig wood; various heights; British Museum(London)

Masks

Funerary masks have been used at all periods. Examples range from the gold masks of

-

Mask of Sitdjehuti; c. 1500 BC; linen, plaster, gold and paint; height: 61 cm (24 in); British Museum (London)

-

Mask ofTjuyu; c. 1387–1350 BC; gold, past of glass, alabaster and other materials; height: 40 cm; Egyptian Museum (Cairo)

-

The Mask of Tutankhamun; c. 1327 BC; gold, glass and semi-precious stones; height: 54 cm (21 in); Egyptian Museum

-

Mummy portrait of a young woman; 100–150 AD; cedar wood, encaustic painting and gold; height: 42 cm, width: 24 cm; Louvre

Ushabti

-

Shabti of Paser, the vizier of Seti I and Ramesses II; 1294–1213 BC; faience; height: 15 cm, width: 4.9 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

Shabti of Sennedjem; 1279–1213 BC; painted limestone; height: 27 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Four ushabtis of Khabekhnet and their box; 1279–1213 BC; painted limestone; height of the ushabtis: 16.7 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Ushabti; 360–343 BC; ceramic and enamel; 26.7 × 7.1 cm; from Saqqara; Museum of Art and History (Geneva, Switzerland)

Art of Meroë

Ancient Egypt shared a long and complex history with the Nile Valley to the south, the region called Nubia (modern Sudan). Beginning with the Kerma culture and continuing with the Kingdom of Kush based at Napata and then Meroë, Nubian culture absorbed Egyptian influences at various times, for both political and religious reasons. The result is a rich and complex visual culture.

The artistic production of Meroë reflects a range of influences. First, it was an indigenous African culture with roots stretching back thousands of years. To this is added the fact that the wealth of Meroë was based on trade with Egypt when it was ruled by the

-

Votive plaque of king Tanyidamani; c. 100 BC; siltstone; 18.5 × 9.5 cm; Walters Art Museum (Baltimore, US)

-

Votive plaque of king Tanyidamani; c. 100 BC; siltstone; 18.5 × 9.5 cm Walters Art Museum

-

Pot from Faras; 300 BC – 350 AD; terracotta; height: 18 cm; Egyptian Museum of Berlin (Germany)

-

Beaker; 300 BC – 350 BAD; terracotta; height: 10.5 cm; Egyptian Museum of Berlin

Egyptian Revival art

Egyptian Revival art is a style in Western art, mainly of the early nineteenth century, in which Egyptian motifs were applied to a wide variety of

Enthusiasm for the artistic style of Ancient Egypt is generally attributed to the excitement over Napoleon's conquest of Egypt and, in Britain, to Admiral Nelson's defeat of Napoleon at the Battle of the Nile in 1798. Napoleon took a scientific expedition with him to Egypt. Publication of the expedition's work, the Description de l'Égypte, began in 1809 and came out in a series though 1826, inspiring everything from sofas with sphinxes for legs, to tea sets painted with the pyramids. It was the popularity of the style that was new, Egyptianizing works of art had appeared in scattered European settings from the time of the Renaissance.

-

The Egyptian Revival portico of the Hôtel Beauharnais from Paris

-

Coin cabinet; by François-Honoré-Georges Jacob-Desmalter; 1809–1819; mahogany with silver; 90.2 x 50.2 x 37.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

1862 lithograph of the Aegyptischer Hof (English: Egyptian court), from the Neues Museum (Berlin)

-

Center table; 1870–1875; rosewood, walnut and marble; 79.4 x 119.4 x 78.7 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Side chair and armchair; 1870–1875; rosewood and prickly juniper veneer; various dimensions; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Pitcher; circa 1872; silver; overall: 28.6 x 15.6 x 21.9 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Design for a costume of Princess Amnéris; by Henri de Montaut; 1879; pencil and watercolor paint; unknown dimensions; in a temporary exhibition called "L'aventure Champollion" at the Site François-Mitterrand, part of the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris

-

Clock; by Tiffany & Co.; circa 1885; marble & bronze; 46 x 51.1 x 19.7 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

The Supreme Constitutional Court of Egypt.

See also

Notes

- ^ It is disputed whether Cleopatra was deliberately depicted as a male or whether a stele made under her father with his portrait was later inscribed with an inscription for Cleopatra. On this and other uncertainties regarding this stele, see Pfeiffer (2015, pp. 177–181).

References

- ^ Redford 1992, p. 6.

- PMID 16371462.

- ^ Genetic data:

- Chicki, L; Nichols, RA; Barbujani, G; Beaumont, MA (2002). "Y genetic data support the Neolithic demic diffusion model". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 99 (17): 11008–11013. PMID 12167671.

- "Estimating the Impact of Prehistoric Admixture on the Genome of Europeans, Dupanloup et al., 2004". Mbe.oxfordjournals.org. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- Semino, O; Magri, C; Benuzzi, G; et al. (May 2004). "Origin, Diffusion, and Differentiation of Y-Chromosome Haplogroups E and J: Inferences on the Neolithization of Europe and Later Migratory Events in the Mediterranean Area, 2004". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 74 (5): 1023–34. PMID 15069642.

- Cavalli-Sforza (1997). "Paleolithic and Neolithic lineages in the European mitochondrial gene pool". Am J Hum Genet. 61 (1): 247–54. PMID 9246011. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- Chikhi (21 July 1998). "Clines of nuclear DNA markers suggest a largely Neolithic ancestry of the European gene". PNAS. 95 (15): 9053–9058. PMID 9671803.

- Chicki, L; Nichols, RA; Barbujani, G; Beaumont, MA (2002). "Y genetic data support the Neolithic demic diffusion model". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 99 (17): 11008–11013.

- ^ Archaeological data:

- Bar Yosef, Ofer (1998). "The Natufian Culture in the Levant, Threshold to the Origins of Agriculture". Evolutionary Anthropology. 6 (5): 159–177. S2CID 35814375.

- Zvelebil, M. (1986). Hunters in Transition: Mesolithic Societies and the Transition to Farming. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 5–15, 167–188.

- Bellwood, P. (2005). First Farmers: The Origins of Agricultural Societies. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

- Dokládal, M.; Brožek, J. (1961). "Physical Anthropology in Czechoslovakia: Recent Developments". Current Anthropology. 2 (5): 455–477. S2CID 161324951.

- Zvelebil, M. (1989). "On the transition to farming in Europe, or what was spreading with the Neolithic: a reply to Ammerman (1989)". Antiquity. 63 (239): 379–383. S2CID 162882505.

- Bar Yosef, Ofer (1998). "The Natufian Culture in the Levant, Threshold to the Origins of Agriculture". Evolutionary Anthropology. 6 (5): 159–177.

- ISBN 0-393-31755-2.

- ^ Eiwanger, Josef (1999). "Merimde Beni-salame". In Bard, Kathryn A. (ed.). Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. London/New York. pp. 501–505.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "picture of the Merimde head" (in German). Auswaertiges-amt.de. Archived from the original on 2 March 2012. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- ^ ISBN 0-19-815034-2.

- ^ a b Gardiner, Alan, Egypt of the Pharaohs (Oxford: University Press, 1964), p. 389.

- ^ a b c Gardiner, Alan, Egypt of the Pharaohs (Oxford: University Press, 1964), p. 390.

- ^ a b "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr.

- ISBN 9780931464966.

- ^ a b c Redford 1992, p. 16.

- ^ Shaw, Ian. & Nicholson, Paul, The Dictionary of Ancient Egypt, (London: British Museum Press, 1995), p. 109.

- ^ Redford 1992, p. 18.

- ^ Redford 1992, p. 17.

- ^ a b c Redford 1992, p. 22.

- ^ Redford 1992, p. 20.

- ^ "Naqada III". Faiyum.com. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- ^ Kinnaer, Jacques. "Early Dynastic Period" (PDF). The Ancient Egypt Site. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- ISBN 978-0-500-51984-4.

- ^ "Old Kingdom of Egypt". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2017-12-04.

- ^ "Statue of Menkaure with Hathor and Cynopolis". The Global Egyptian Museum.

- ^ David, Rosalie (2002). Religion and Magic in Ancient Egypt. Penguin Books. p. 156

- ^ Robins 2008, p. 90.

- ^ Robins 2008, p. 109.

- ^ "Guardian Figure". www.metmuseum.org. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 9 February 2022.

- ^ Bard 2015, p. 188.

- ^ Van de Mieroop 2010, p. 131.

- S2CID 199601200.

- ^ Curry, Andrew (2018). "The Rulers of Foreign Lands - Archaeology Magazine". www.archaeology.org.

- ^ a b c el-Shahawy 2005, p. 160.

- ^ Bietak 1999, p. 379.

- ^ Müller 2018, p. 212.

- ^ Bard 2015, p. 213.

- ^ Van de Mieroop 2021, pp. 151–153.

- ^ Redford 1992, p. 122.

- ^ Candelora 2018, p. 54.

- ISBN 978-3-7347-3964-4.

- ^ Candelora, Danielle. "The Hyksos". www.arce.org. American Research Center in Egypt.

- ^ Roy 2011, pp. 291–292.

- ^ "The Rulers of Foreign Lands". Archaeology Magazine.

A head from a statue of an official dating to the 12th or 13th Dynasty (1802–1640 B.C.) sports the mushroom-shaped hairstyle commonly worn by non-Egyptian immigrants from western Asia such as the Hyksos.

- ISBN 978-1-4443-6077-6.

- ISBN 978-1-108-08291-4.

- ^ "Statue". The British Museum.

- ^ O'Connor 2009, pp. 116–117.

- ISBN 978-0-500-77162-4.

- ^ Daressy 1906, pp. 115–120.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-815034-3.

- ^ a b c d e Robin, Gay (2008). The Art of Ancient Egypt. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. pp. 127–193.

- ^ a b c Aldred, Cyril (1951). New Kingdom Art in Ancient Egypt during the Eighteenth Dynast. London: Alec Tiranti.

- ISBN 9780500051597.

The foreigners of the fourth register, with long hairstyles and calf-length fringed robes, are labeled Chiefs of Retjenu, the ancient name tor the Syrian region. Like the Nubians, they come with animals, in this case horses, an elephant, and a bear; they also offer weapons and vessels most likely filled with precious substance.

- ISBN 978-1-317-39195-1.

- ISBN 0801436583.

- ^ a b Fazzini, Richard (October 1973). "ART from the Age of Akhenaten". Archaeological Institute of America. 26 (4): 298–302 – via JSTOR.

- – via JSTOR.

- ^ Brand, Peter (September 25, 2010). "Reuse and Restoration". UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology. 1 (1) – via Escholarship.

- ^ Aldred, Cyril (1951). New Kingdom Art in Ancient Egypt. New Kindgom: Alec Tiranti.

- ISBN 978-0-87099-907-9.

- ^ JSTOR 3822074.

- JSTOR 3822074.

- ^ Robins 2008, p. 216.

- ^ a b c "Taharqa et Hémen". Louvre Collections.

- ^ Razmjou, Shahrokh (1954). Ars orientalis; the arts of Islam and the East. Freer Gallery of Art. pp. 81–101.

- ISBN 978-0-500-20428-3.

- ^ ISBN 0674046609.

- ^ "The long skirt shown wrapped around this statue’s body and tucked in at the upper edge of the garment is typically Persian. The necklace, called a torque, is decorated with images of ibexes, symbols in ancient Persia of agility and sexual prowess. The depiction of this official in Persian dress may have been a demonstration of loyalty to the new rulers." "Egyptian Man in a Persian Costume". www.brooklynmuseum.org. Brooklyn Museum.

- ^ Smith 1991, pp. 206, 208–209.

- ^ a b Smith 1991, p. 210.

- ^ Smith 1991, p. 205.

- ^ Smith 1991, p. 206.

- ^ Smith 1991, p. 207.

- ^ Smith 1991, p. 209.

- ^ Smith 1991, p. 208.

- ^ Smith 1991, pp. 208–209, 210.

- ^ Tiradritti 2005, pp. 21, 212.

- ISBN 978-90-5867-239-1.

Trajan was, in fact, quite active in Egypt. Separate scenes of Domitian and Trajan making offerings to the gods appear on reliefs on the propylon of the Temple of Hathor at Dendera. There are cartouches of Domitian and Trajan on the column shafts of the Temple of Knum at Esna, and on the exterior a frieze text mentions Domitian, Trajan, and Hadrian

- ISBN 0-87846-661-4

- ISBN 978-0-500-51984-4.

- ^ Smith & Simpson 1998, p. 33.

- ^ Smith & Simpson 1998, pp. 12–13 and note 17.

- ^ Smith & Simpson 1998, pp. 21–24.

- ^ Smith & Simpson 1998, pp. 170–178, 192–194.

- ^ Smith & Simpson 1998, pp. 102–103, 133–134.

- ^ The Art of Ancient Egypt. A resource for educators (PDF). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 44. Retrieved July 7, 2013.

- ^ Constantin Daniel (1980). Arta Egipteană și Civilizațiile Mediteraneene (in Romanian). Bucharest: Editura Meridiane. p. 54.

- ^ a b c Historical Atlas of Ancient Egypt, Bill Manley (1996) p. 83

- ^ "Color in Ancient Egypt". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2018-10-04.

- ^ Wilkinson 2008, p. 55.

- ^ a b Lacovara, Peter; Markowitz, Yvonne J. (2001). "Materials and Techniques in Egyptian Art". The Collector's Eye: Masterpieces of Egyptian Art from the Thalassic Collection, Ltd. Atlanta: Michael C. Carlos Museum. pp. XXIII–XXVIII.

- ^ Wilkinson 2008, p. 78.

- ^ Wilkinson 2008, p. 92.

- ^ Wilkinson 2008, pp. 73 & 74.

- ^ Smith, William (1999). The Art and Architecture of Ancient Egypt (The Yale University Press Pelican History of Art). Yale: Yale University Press. pp. 23–24.

- ^ Wilkinson 2008, pp. 153 & 154.

- ^ Wilkinson 2008, p. 263.

- ^ Wilkinson 2008, pp. 134 & 135.

- ^ Smith & Simpson 1998, p. 2.

- ^ Smith & Simpson 1998, pp. 4–5, 208–209.

- ^ Smith & Simpson 1998, pp. 89–90.

- JSTOR 20297188.

- ISBN 978-0-7148-7502-6.

- ^ Wilkinson 2008, p. 235.

- ISBN 978-0-500-51984-4.

- ^ Wilkinson 2008, p. 197.

- ^ Grove[full citation needed]

- ^ Mark, Joshua J. (24 March 2016). "Egyptian Book of the Dead". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2019-04-23.

- ISBN 978-0-500-29148-1.

- ^ Jenner, Jan (2008). Ancient Civilizations. Toronto: Scholastic.

- ^ Wilkinson 2008, pp. 119 & 120.

- ^ Wilkinson 2008, pp. 24 & 25.

- ^ Gahlin, Lucia (2014). Egypt God, Myths and Religion. Hermes House. p. 159.

- ^ Wilkinson 2008, p. 87.

- ^ Ecaterina Oproiu, Tatiana Corvin (1975). Enciclopedia căminului (in Romanian). Editura științifică și enciclopedică. p. 17.

- ^ Graur, Neaga (1970). Stiluri în arta decorativă (in Romanian). Cerces. p. 16 & 17.

- ^ Wilkinson 2008, p. 53.

- ^ Wilkinson 2008, p. 57.

- ^ Wilkinson 2008, p. 161.

- ^ Wilkinson 2008, p. 230.

- ^ Wilkinson 2008, pp. 53, 54 & 55.

- ^ Wilkinson 2008, p. 48.

- ^ Wilkinson 2008, p. 144.

- ^ Wilkinson 2008, p. 226.

- ^ Sara Ickow. "Egyptian Revival". The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Sources

- Bard, Kathryn A. (2015). An Introduction to the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt (2nd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 9780470673362.

- el-Shahawy, Abeer (2005). The Egyptian Museum in Cairo: A Walk Through the Alleys of Ancient Egypt. Farid Atiya Press. ISBN 977-17--2183-6.

- ISBN 9781134665259.

- Evers, Hans Gerhard: Staat aus dem Stein – Denkmäler, Geschichte und Bedeutung der ägyptischen Plastik während des Mittleren Reichs. 2 volumes, Bruckmann, Munich 1929 (download at archiv.evers.frydrych.org).

- Müller, Vera (2018). "Chronological Concepts for the Second Intermediate Period and Their Implications for the Evaluation of Its Material Culture". In Forstner-Müller, Irene; Moeller, Nadine (eds.). THE HYKSOS RULER KHYAN AND THE EARLY SECOND INTERMEDIATE PERIOD IN EGYPT: PROBLEMS AND PRIORITIES OF CURRENT RESEARCH. Proceedings of the Workshop of the Austrian Archaeological Institute and the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, Vienna, July 4 – 5, 2014. Holzhausen. pp. 199–216. ISBN 978-3-902976-83-3.

- ISBN 3-8053-2591-6.

- Candelora, Danielle (2018). "Entangled in Orientalism: How the Hyksos Became a Race". Journal of Egyptian History. 11 (1–2): 45–72. S2CID 216703371.

- Roy, Jane (2011). The Politics of Trade: Egypt and Lower Nubia in the 4th Millennium BC. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-19610-0.

- Pfeiffer, Stefan (2015). Griechische und lateinische Inschriften zum Ptolemäerreich und zur römischen Provinz Aegyptus. Einführungen und Quellentexte zur Ägyptologie (in German). Vol. 9. Münster: Lit.

- O'Connor, David (2009). "Egypt, the Levant, and the Aegean: From the Hyksos Period to the Rise of the New Kingdom". In Aruz, Joan; Benzel, Kim; Evans, Jean M. (eds.). Beyond Babylon : art, trade, and diplomacy in the second millennium B.C. Yale University Press. pp. 108–122. ISBN 9780300141436.

- Daressy, Georges (1906). "Un poignard du temps des Rois Pasteurs". Annales du Service des Antiquités de l'Égypte. 7: 115–120.

- ISBN 978-0-691-03606-9.

- Robins, Gay (2008). The Art of Ancient Egypt. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-03065-7.

- Smith, R.R.R. (1991). Hellenistic Sculpture, a handbook. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0500202494.

- Smith, W. Stevenson; Simpson, William Kelly (1998). The Art and Architecture of Ancient Egypt. Penguin/Yale History of Art (3rd ed.). Yale University Press. ISBN 0300077475.

- Tiradritti, Francesco (2005). "The Return of Isis in Egypt: Remarks on Some Statues of Isis and the Diffusion of Her Cult in the Graeco-Roman World". In Hoffmann, Adolf (ed.). Ägyptische Kulte und ihre Heiligtümer im Osten des Römischen Reiches. Internationales Kolloquium 5./6. September 2003 in Bergama (Türkei). Ege Yayınları. ISBN 978-1-55540-549-6.

- ISBN 978-1-4051-6070-4.

- ISBN 978-1-1196-2087-7.

- Wilkinson, Toby (2008). Dictionary of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-20396-5.

Further reading

Hill, Marsha (2007). Gifts for the gods: images from Egyptian temples. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

External links

- Ancient Egyptian Art – Aldokkan

- Senusret Collection: A well-annotated introduction to the arts of Egypt

![Tag depicting king Den; c. 3000 BC; ivory; 4.5 × 5.3 cm; from Abydos (Egypt); British Museum (London)[21]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b3/MacGregor_Plate_%28with_background%29.jpg/170px-MacGregor_Plate_%28with_background%29.jpg)

![Statue of Menkaure with Hathor and Cynopolis; 2551–2523 BC; schist; height: 95.5 cm; Egyptian Museum (Cairo). Demonstrates a group statue with Old Kingdom features and proportions.[23]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/ac/Menkaura.jpg/113px-Menkaura.jpg)

![A guardian statue which reflects the facial features of the reigning king, probably Amenemhat I or Senwosret I, and which functioned as a divine guardian for the imiut. Made of cedar wood and plaster c. 1919–1885 BC[27]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/0b/GuardianStatueofAmenemhmatII.jpg/127px-GuardianStatueofAmenemhmatII.jpg)

![An official wearing the "mushroom-headed" hairstyle also seen in contemporary paintings of Western Asiatic foreigners such as in the tomb of Khnumhotep II, at Beni Hasan. Excavated in Avaris, the Hyksos capital. Staatliche Sammlung für Ägyptische Kunst.[40][41][42][43]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a1/Asiatic_official_Munich_%28retouched%29.jpg/127px-Asiatic_official_Munich_%28retouched%29.jpg)

![Lion inscribed with the name of the Hyksos ruler Khyan, found in Baghdad, suggesting relations with Babylon. The prenomen of Khyan and epithet appear on the breast. British Museum, EA 987.[44][45]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/26/Khyan.jpg/170px-Khyan.jpg)

![Electrum dagger handle of a soldier of Hyksos Pharaoh Apepi, illustrating the soldier hunting with a short bow and sword. Inscriptions: "The perfect god, the lord of the two lands, Nebkhepeshre Apepi" and "Follower of his lord Nehemen", found at a burial at Saqqara.[46] Now at the Luxor Museum.[47][48]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b3/Hyksos_dagger_handle.jpg/170px-Hyksos_dagger_handle.jpg)