Artificial cranial deformation

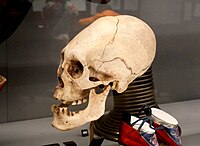

Right: Elongated skull excavated in Samarkand (dated 600–800 CE), Afrasiab Museum of Samarkand

Artificial cranial deformation or modification, head flattening, or head binding is a form of

Typically, the alteration is carried out on an infant, when the skull is most pliable. In a typical case, head binding begins approximately a month after birth and continues for about six months.

History

Intentional cranial deformation predates

The earliest suggested examples were once thought to include Neanderthals and the Proto-

The earliest written record of cranial deformation comes from Hippocrates in about 400 BCE. He described a group known as the Macrocephali or Long-heads, who were named for their practice of cranial modification.[7]

Eurasia

In the

In the

In western Germanic tribes, artificial skull deformations rarely have been found.[19]

-

Female skull found in Mozs, Hungary, c. 5th century

-

Landesmuseum Württemberg elongated skull, early 6th century Alemannic culture

Elongated skulls of three women have been discovered among

The custom of binding babies' heads in Europe in the twentieth century, though dying out at the time, was still extant in France, and also found in pockets in

Americas

In the Americas, the

The practice of cranial deformation was also practiced by the

-

Proto Nazca elongated skull, c. 200–100 BCE

-

An elongated female human skull in Olmec and Gulf Coast Gallery, in the National Museum of Anthropology (Mexico)

-

Tiwanaku skull from Bolivia, on display in the Horniman Museum, London

Austronesia

The

They were first recorded in 1604 by the Spanish priest Diego Bobadilla. He reported that in the central Philippines, people placed the heads of children between two boards to horizontally flatten their skulls towards the back, and that they viewed this as a mark of beauty. Other historic sources confirmed the practice, further identifying it as also being a practice done by the nobility (

People with flattened foreheads were known as tinangad. People with unmodified crania were known as ondo, which literally means "packed tightly" or "overstuffed", reflecting the social attitudes towards unshaped skulls (similar to the binatakan and puraw distinctions in Visayan tattooing). People with flattened backs of the head were known as puyak, but it is unknown whether puyak were intentional.[32]

Other

It was also practiced at least into the 1930s on the island of New Britain in the Bismarck Archipelago of Papua New Guinea.[34]

Africa

In Africa, the Mangbetu elongated their heads. Traditionally, babies' heads were wrapped tightly with cloth, called "Limpombo", in order to give them this distinctive appearance. The practice began dying out in the 1950s.[citation needed]

Japan

On the southern Japanese island of Tanegashima, from the third century to the seventh century, a group potentially bound the skulls of babies to flatten the back of the skull, possibly as an expression of group identity to facilitate the trade of shell goods. [35]

China

Cranial deformation was also practiced in the Neolithic period at the Houtaomuga Site in Northeast China.[36] Most had fronto-occipital modification, but there were other types of modification discovered, also. It was found that the practice had been practiced for thousands of years, some skulls being much older than others.

Methods and types

Deformation usually begins just after birth for the next couple of years until the desired shape has been reached or the child rejects the apparatus.[22][page needed][3][37]

There is no broadly established classification system for cranial deformations, and many scientists have developed their own classification systems without agreeing on a single system for all forms observed.[38] An example of an individual system is that of E. V. Zhirov, who described three main types of artificial cranial deformation—round, fronto-occipital, and sagittal—for occurrences in Europe and Asia, in the 1940s.[39]: 82

-

Various methods used by the Mayan people to shape a child's head

-

An anatomical illustration from the 1921 German edition of Anatomie des Menschen: ein Lehrbuch für Studierende und Ärzte with Latin terminology

Motivations and theories

According to one modern theory, cranial deformation was likely performed to signify group affiliation

Historically, there have been a number of various theories regarding the motivations for these practices.

It has also been considered possible that the practice of cranial deformation originates from an attempt to emulate those groups of the population in which elongated head shape was a natural condition. The skulls of some

the same formation [i.e. absence of the signs of artificial pressure] of the head presents itself in children yet unborn; and of this truth we have had convincing proof in the sight of a foetus, enclosed in the womb of a mummy of a pregnant woman, which we found in a cave of Huichay, two leagues from

Huancas. We present the reader with a drawing of this conclusive and interesting proof in opposition to the advocates of mechanical action as the sole and exclusive cause of the phrenological form of the Peruvian race.[43]

P. F. Bellamy makes a similar observation about the two elongated skulls of infants, which were discovered and brought to England by a "Captain Blankley" and handed over to the Museum of the Devon and Cornwall Natural History Society in 1838. According to Bellamy, these skulls belonged to two infants, female and male, "one of which was not more than a few months old, and the other could not be much more than one year."[44] He writes,

It will be manifest from the general contour of these skulls that they are allied to those in the Museum of the College of Surgeons in London, denominated Titicacans. Those adult skulls are very generally considered to be distorted by the effects of pressure; but in opposition to this opinion Dr. Graves has stated that "a careful examination of them has convinced him that their peculiar shape cannot be owing to artificial pressure;" and to corroborate this view, we may remark that the peculiarities are as great in the child as in the adult, and indeed more in the younger than in the elder of the two specimens now produced: and the position is considerably strengthened by the great relative length of the large bones of the cranium; by the direction of the plane of the occipital bone, which is not forced upwards, but occupies a place in the under part of the skull; by the further absence of marks of pressure, there being no elevation of the vertex nor projection of either side; and by the fact of there being no instrument nor mechanical contrivance suited to produce such an alteration of form (as these skulls present) found in connexion with them.[45]

Health effects

There is no statistically significant difference in

See also

References

- ^ Taipale, Eric (January 28, 2022). "Tracing the History and Health Impacts of Skull Modification". Discover Magazine.

- ^ .

- ^ S2CID 144182791.

- S2CID 85239949.

- JSTOR 41496548.

- ^ K.O. Lorentz (2010) "Ubaid head shaping," in Beyond the Ubaid (R.A. Carter & G. Philip, Eds.), pp. 125-148.[full citation needed]

- ^ Hippocrates of Cos (1923) [ca. 400 BCE] Airs, Waters, and Places, Part 14, e.g., Loeb Classic Library Vol. 147, pp. 110–111 (W. H. S. Jones, transl.), DOI: 10.4159/DLCL.hippocrates_cos-airs_waters_places.1923, see [1]. Alternatively, the Adams 1849 and subsequent English editions (e.g., 1891), The Genuine Works of Hippocrates (Francis Adams, transl.), New York, NY, USA: William Wood, at the [MIT] Internet Classics Archive (Daniel C. Stevenson, compiler), see [2]. Alternatively, the Clifton 1752 English editions, "Hippocrates Upon Air, Water, and Situation; Upon Epidemical Diseases; and Upon Prognosticks, In Acute Cases especially. To which is added…" Second edition, pp. 22-23 (Francis Clifton, transl.), London, GBR: John Whiston and Benj. White; and Lockyer Davis, see [3]. All web versions accessed 1 August 2015.

- ISBN 978-1-4744-0030-5.

- ^ "A Silk Road Renaissance - Archaeology Magazine". www.archaeology.org.

- ^ The Hephthalites: Archaeological And Historical Analysis by Aydogdy Kurbanov, page 60/ digital page 65 - https://refubium.fu-berlin.de/bitstream/handle/fub188/8366/01_Text.pdf

- ISBN 978-2-87772-337-4., p. 15

- ^ ISBN 978-94-93194-00-7.

- JSTOR 44710198.

- PMID 21121717.

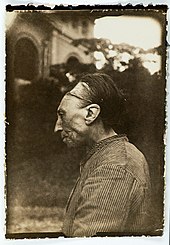

- ^ "Attila und die Hunnen - Schädelrekonstruktion und Atelierfoto". Das Historische Museum der Pfalz (in German).

- ^ Bachrach, Bernard S. (1973) A History of the Alans in the West: From Their First Appearance in the Sources of Classical Antiquity Through the Early Middle Ages, pp. 67-69, Minneapolis, MN, USA: University of Minnesota Press.

- ^ Herbert Schutz, The Germanic Realms in Pre-Carolingian Central Europe, 400-750, P. Lang, 2000, p. 62.

- ISBN 951-650-196-6.

- ^ Pany, Doris & Karin Wiltschke-Schrotta, "Artificial cranial deformation in a migration period burial of Schwarzenbach, Lower Austria," ViaVIAS, no. 2, pp. 18-23, Vienna, AUT: Vienna Institute for Archaeological Science.

- ^ Anderson, Sonja, Vikings May Have Used Body Modification as a ‘Sign of Identification’, Smiuthsonian, April 8, 2024

- ^ Three strange skull modifications discovered in Viking women, Arkeonews, April 14, 2024

- ^ a b c d Eric John Dingwall, Eric John (1931) "Later artificial cranial deformation in Europe (Ch. 2)," in Artificial Cranial Deformation: A Contribution to the Study of Ethnic Mutilations, pp. 46-80, London, GBR:Bale, Sons & Danielsson, see "Chapter 2" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-09-12. Retrieved 2014-02-20.[page needed] and [4][page needed], both accessed 1 August 2015.

- ^ Delaire, MMJ; Billet, J (1964). "Considérations sur les déformations crâniennes intentionnelles" (PDF). Rev Stomatol. 69: 535–541.

- S2CID 9347535.

- ^ Tiesler, Vera (Autonomous University of Yucatan) (1999). Head Shaping and Dental Decoration Among the Ancient Maya: Archeological and Cultural Aspects (PDF). 64th Meeting of the Society of American Archaeology. Chicago, IL, USA. pp. 1–6. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- ^ Tiesler, Vera (2012). "Studying cranial vault modifications in ancient Mesoamerica". Journal of Anthropological Sciences. 90: 1–26.

- ^ Tiesler, Vera & Ruth Benítez (2001). "Head shaping and dental decoration: Two biocultural attributes of cultural integration and social distinction among the Ancient Maya," American Journal of Physical Anthropology, Annual Meeting Supplement, 32, p. 149".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Elliott Shaw, 2015, "Choctaw Religion," at Overview Of World Religions, Carlisle, CMA, GBR: University of Cumbria Department of Religion and Ethics, see [5], accessed 1 August 2015.

- ^ Hudson, Charles (1976). The Southeastern Indians. University of Tennessee Press. p. 31.

- doi:10.1002/oa.1180.

- ^ S2CID 53623866.

- ^ ISBN 9789715501354.

- ^ Ratzel, Friedrich (1896). "The History of Mankind". MacMillan, London. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 4 October 2009.

- ^ Blackwood, Beatrice, and P. M. Danby. "A study of artificial cranial deformation in New Britain." The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 85, no. 1/2 (1955): 173-191.

- ^ Noriko Seguchi, James Frances Loftus III, Shiori Yonemoto, Mary-Margaret Murphy. Investigating intentional cranial modification: A hybridized two-dimensional/three-dimensional study of the Hirota site, Tanegashima, Japan. PLOS ONE. PLOS ONE Online

- ^ Zhang, Qun, Peng Liu, Hui‐Yuan Yeh, Xingyu Man, Lixin Wang, Hong Zhu, Qian Wang, and Quanchao Zhang. "Intentional cranial modification from the Houtaomuga Site in Jilin, China: Earliest evidence and longest in situ practice during the Neolithic Age." American Journal of Physical Anthropology 169, no. 4 (2019): 747-756. Summary online

- PMID 10068066.

- ^ S2CID 163711418.

- ^ E. V. Zhirov (1941).[full citation needed]

- ^ PMID 7501099.

- ^ Tubbs, Salter, and Oaks, 2006.[full citation needed]

- ^ Colin Barras (13 October 2014). "Why early humans reshaped their children's skulls". BBC Earth. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ Rivero and Tschudi (1852) Antigüedades peruanas (Peruvian Antiquities), issue 1851/1852.

- ^ Bellamy, P. F. (1842) "A brief Account of two Peruvian Mummies in the Museum of the Devon and Cornwall Natural History Society, in Annals and Magazine of Natural History, X (October).[6]

- ^ P. F. Bellamy: A brief Account of two Peruvian Mummies in the Museum of the Devon and Cornwall Natural History Society. In: The Annals and Magazine of Natural History. Bd. 10, No. 63, 1842, p.p 95–100.

- PMID 12923900.

Further reading

- Trinkaus, Erik (1982). The Shanidar Neandertals. New York, NY, USA: Academic Press.

- Tiesler, Vera (2013) The Bioarchaeology of Artificial Cranial Modifications: New Approaches to Head Shaping and its Meanings in Pre-Columbian Mesoamerica and Beyond [Vol. 7, Springer Interdisciplinary Contributions to Archaeology], Berlin, NY, USA:Springer Science & Business, ISBN 1461487609, see [7], accessed 1 August 2015.

- FitzSimmons, Ellen; Jack H. Prost & Sharon Peniston (1998) "Infant Head Molding, A Cultural Practice," Arch. Fam. Med., 7 (January/February).

- Adebonojo, F. O. (1991). "Infant head shaping". J. Am. Med. Assoc. 265 (9): 1179. PMID 1996005.

- Henshen, F. (1966) The Human Skull: A Cultural History, New York, NY, USA: Frederick A. Praeger.