Artiodactyl

This article is missing information about cetacean traits and physical traits uniting cetaceans with terrestrial artiodactyls. (July 2023) |

| Artiodactyls | |

|---|---|

| |

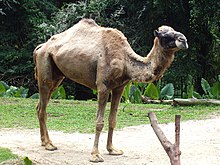

| Clockwise from center: American bison (Bison bison), dromedary (Camelus dromedarius), wild boar (Sus scrofa), orca (Orcinus orca), red deer (Cervus elaphus), and giraffe (Genus: Giraffa) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Clade: | Scrotifera |

| Grandorder: | Ferungulata |

| Clade: | Pan-Euungulata |

| Mirorder: | Euungulata |

| Clade: | Paraxonia

|

| Order: | Artiodactyla Owen, 1848 |

| Subdivisions | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Cetartiodactyla | |

Artiodactyls are

The roughly 270 land-based even-toed ungulate species include

Evolutionary history

The oldest fossils of even-toed ungulates date back to the early

Two formerly widespread, but now extinct, families of even-toed ungulates were

The camels (

South America was settled by even-toed ungulates only in the Pliocene, after the land bridge at the Isthmus of Panama formed some three million years ago. With only the peccaries, lamoids (or llamas), and various species of capreoline deer, South America has comparatively fewer artiodactyl families than other continents, except Australia, which has no native species.

Taxonomy and phylogeny

The classification of artiodactyls was hotly debated because ocean-dwelling cetaceans evolved from land-dwelling even-toed ungulates. Some semiaquatic even-toed ungulates (hippopotamuses) are more closely related to ocean-dwelling cetaceans than to other even-toed ungulates.

Phylogenetic classification only recognizes

Classification

- Order Artiodactyla/Clade Cetartiodactyla[4][6]

- Family †Diacodexeidae

- Family †Amphimerycidae

- Family †Robiacinidae

- Family †Cainotheriidae

- Suborder Tylopoda

- Family †Anoplotheriidae?

- Family †Merycoidodontidae

- Family †Agriochoeridae

- Family Camelidae: camels and lamoids or llamas (7 extant and 13 extinct species)

- Family †Oromerycidae

- Family †Xiphodontidae?

- Family †Protoceratidae?

- Clade Artiofabula

- Suborder Suina

- Family Suidae: pigs (19 species)

- Family Tayassuidae: peccaries (4 species)

- Family †Sanitheriidae

- Family †Doliochoeridae

- Clade Cetruminantia

- Clade Cetancodontamorpha

- Genus †Andrewsarchus?

- Family †Entelodontidae

- Suborder Whippomorpha

- Family †Raoellidae

- Superfamily Dichobunoidea – paraphyletic to Cetacea and Raoellidae

- Family †Dichobunidae

- Family †Helohyidae

- Family †Choeropotamidae

- Family †Cebochoeridae (Family contains Cebochoerus)

- Family †Mixtotheriidae

- Infraorder Ancodonta

- Family †Anthracotheriidae – paraphyletic to Hippopotamidae

- Family Hippopotamidae: hippos (two species)

- Infraorder Cetacea: whales (about 90 species)

- Parvorder †Archaeoceti

- Family †Pakicetidae

- Family †Ambulocetidae

- Family †Remingtonocetidae

- Family †Basilosauridae

- Clade Neoceti

- Parvorder Mysticeti: baleen whales

- Superfamily Balaenoidea: right whales

- Family Balaenidae: greater right whales (four species)

- Family Cetotheriidae: pygmy right whale (one species)

- Superfamily Balaenopteroidea: large baleen whales

- Family Balaenopteridae: slender-back rorquals and humpback whale(eight species)

- Family Eschrichtiidae: gray whale (one species)

- Family

- Superfamily Balaenoidea: right whales

- Parvorder Odontoceti: toothed whales

- Superfamily Delphinoidea: oceanic dolphins, porpoises, and others

- Family Delphinidae: oceanic true dolphins(38 species)

- Family Monodontidae: Arctic whales; narwhal and beluga (two species)

- Family Phocoenidae: porpoises(six species)

- Family

- Superfamily Physeteroidea: sperm whales

- Family Kogiidae: lesser sperm whales (two species)

- Family Physeteridae: sperm whale(one species)

- Superfamily Platanistoidea: river dolphins

- Family Iniidae: South American river dolphins (two species)

- Family Chinese river dolphin(one species, possibly extinct)

- Family Platanistidae: South Asian river dolphin (one species)

- Family Pontoporiidae: La Plata dolphin (one species)

- Superfamily Ziphioidea

- Family Ziphiidae: beaked whales(22 species)

- Family

- Superfamily Delphinoidea: oceanic dolphins, porpoises, and others

- Parvorder

- Parvorder †Archaeoceti

- Total-group Ruminantia

- Family †Anoplotheriidae?

- Family †Xiphodontidae?

- Family †Cainotheriidae?

- Family †Protoceratidae?

- Suborder Ruminantia

- Infraorder Tragulina

- Family †Leptomerycidae

- Family †Hypertragulidae

- Family †Praetragulidae

- Family †Gelocidae

- Family †Bachitheriidae

- Family Tragulidae: chevrotains (ten species)

- Family †Archaeomerycidae

- Family †Lophiomerycidae

- Infraorder Pecora

- Family †Palaeomerycidae

- Family †Dromomerycidae

- Family Antilocapridae: pronghorn (one species)

- Family †Climacoceratidae

- Family Giraffidae: okapi and four species of giraffe (five species total)

- Family †Hoplitomerycidae

- Family Cervidae: deer(49 species)

- Family Moschidae: musk deer (seven species)

- Family goat-antelope, antelope, and others (135 species)

- Infraorder Tragulina

- Clade Cetancodontamorpha

- Suborder Suina

Research history

In the 1990s, biological systematics used not only morphology and fossils to classify organisms, but also molecular biology. Molecular biology involves sequencing an organism's DNA and RNA and comparing the sequence with that of other living beings—the more similar they are, the more closely they are related. Comparison of even-toed ungulate and cetaceans genetic material has shown that the closest living relatives of whales and hippopotamuses is the paraphyletic group Artiodactyla.

Dan Graur and Desmond Higgins were among the first to come to this conclusion, and included a paper published in 1994.

In 2001, the fossil limbs of a

The oldest cetaceans date back to the early Eocene (53 million years ago), whereas the oldest known hippopotamus dates back only to the Miocene (15 million years ago). The hippopotamids are descended from the anthracotheres, a family of semiaquatic and terrestrial artiodactyls that appeared in the late Eocene, and are thought to have resembled small- or narrow-headed hippos. Research is therefore focused on anthracotheres (family Anthracotheriidae); one dating from the Eocene to Miocene was declared to be "hippo-like" upon discovery in the 19th century. A study from 2005 showed that the anthracotheres and hippopotamuses had very similar skulls, but differed in the adaptations of their teeth. It was nevertheless believed that cetaceans and anthracothereres descended from a common ancestor, and that hippopotamuses developed from anthracotheres. A study published in 2015 confirmed this, but also revealed that hippopotamuses were derived from older anthracotherians.[11][16] The newly introduced genus Epirigenys from Eastern Africa is thus the sister group of hippos.

Historical classification of Artiodactyla

Internal morphology (mainly the stomach and the molars) were used for classification.

The taxonomy that was widely accepted by the end of the 20th century was:[18][full citation needed]

Even-toed ungulates

|

|

Historical classification of Cetacea

Modern cetaceans are highly adapted sea creatures which, morphologically, have little in common with land mammals; they are similar to other

The suspected relations can be shown as follows:[16][19][page needed]

Paraxonia

|

| ||||||

Inner systematics

Molecular findings and morphological indications suggest that artiodactyls, as traditionally defined, are paraphyletic with respect to cetaceans. Cetaceans are deeply nested within the former; the two groups together form a

The presumed lineages within Artiodactyla can be represented in the following cladogram:[20][21][22][23][24]

| Artiodactyla |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The four summarized Artiodactyla taxa are divided into ten extant families:[25]

- The camelids (Tylopoda) comprise only one family, Camelidae. It is a species-poor artiodactyl suborder of North American origin[26] that is well adapted to extreme habitats—the dromedary and Bactrian camels in the Old World deserts and the guanacos, llamas, vicuñas, and alpacas in South American high mountain regions.

- The pig-like creatures (Suina) are made up of two families:

- The pigs (domestic pig.

- The peccaries (Tayassuidae) are named after glands on their belly and are indigenous to Central and South America.

- The pigs (

- The ruminants (Ruminantia) consist of six families:

- The mouse deer (Tragulidae) are the smallest and most primitive even-toed-ruminants; they inhabit forests of Africa and Asia.

- The giraffe-like creatures (Giraffidae) are composed of two species: the giraffe and the okapi.

- The musk deer (Moschidae) is indigenous to East Asia.

- The antilocaprids (Antilocapridae) of North America comprise only one extant species: the pronghorn.

- The deer ( (caribou).

- The bovids (Bovidae) are the most species-rich. Among them are cattle, sheep, caprines, and antelopes.

- The mouse deer (

- The whippomorphans include hippos and cetaceans:

- The hippos (pygmy hippo.

- The whales (Mysticeti)

- The hippos (

Although deer, musk deer, and pronghorns have traditionally been summarized as cervids (Cervioidea), molecular studies provide different—and inconsistent—results, so the question of phylogenetic systematics of infraorder Pecora (the horned ruminants) for the time being, cannot be answered.

Anatomy

Artiodactyls are generally

Almost all even-toed ungulates have fur, with the exception being the nearly hairless hippopotamus. Fur varies in length and coloration depending on the habitat. Species in cooler regions can shed their coat. Camouflaged coats come in colors of yellow, gray, brown, or black tones.

Limbs

Even-toed ungulates bear their name because they have an even number of

-

Hippopotamuses have all four toes pointing out.

-

For pigs and other biungulates the second and fifth toes are directed backwards.

-

When camels have only two toes present, the claws are transformed into nails.

When camels have only two toes present, the claws are transformed into nails (while both are made of keratin, claws are curved and pointed while nails are flat and dull).[27] These claws consist of three parts: the plate (top and sides), the sole (bottom), and the bale (rear). In general, the claws of the forelegs are wider and blunter than those of the hind legs, and they are farther apart. Aside from camels, all even-toed ungulates put just the tip of the foremost phalanx on the ground.[28]

In even-toed ungulates, the bones of the stylopodium (upper arm or thigh bone) and

Head

Many even-toed ungulates have a relatively large head. The skull is elongated and rather narrow; the frontal bone is enlarged near the back and displaces the parietal bone, which forms only part of the side of the cranium (especially in ruminants).

Horns and antlers

Four families of even-toed ungulates have cranial appendages. These Pecora (with the exception of the musk deer), have one of four types of cranial appendages: true horns, antlers, ossicones, or pronghorns.[29]

True horns have a bone core that is covered in a permanent sheath of keratin, and are found only in the

All these cranial appendages can serve for posturing, battling for mating privilege, and for defense. In almost all cases, they are sexually dimorphic, and are often found only on the males. One exception is the species Rangifer tarandus, known as reindeer in Europe or caribou in North America, where both sexes can grow antlers yearly, though the females' antlers are typically smaller and not always present.

Teeth

Dental formula

|

I | C | P | M | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30–44 | = | 0–3 | 0–1 | 2–4 | 3 |

| 1–3 | 1 | 2–4 | 3 | ||

There are two trends in terms of teeth within Artiodactyla. The Suina and hippopotamuses have a relatively large number of teeth (with some pigs having 44); their dentition is more adapted to a squeezing

The

The molars of porcine have only a few bumps. In contrast, camels and ruminants have bumps that are crescent-shaped cusps (selenodont).

Senses

Artiodactyls have a well-developed sense of smell and sense of hearing. Unlike many other mammals, they have a poor sense of sight—moving objects are much easier to see than stationary ones. Similar to many other prey animals, their eyes are on the sides of the head, giving them an almost panoramic view.

Digestive system

The

Unlike other even-toed ungulates, pigs have a simple sack-shaped

Genitourinary system

The penises of even-toed ungulates have an S-shape at rest and lie in a pocket under the skin on the belly. The corpora cavernosa are only slightly developed; and an erection mainly causes this curvature to extend, which leads to an extension, but not a thickening, of the penis. Cetaceans have similar penises.[35] In some even-toed ungulates, the penis contains a structure called the urethral process.[36][37][38]

The testicles are located in the scrotum and thus outside the abdominal cavity. The ovaries of many females descend—as the testicles descend of many male mammals—and are close to the pelvic inlet at the level of the fourth lumbar vertebra. The uterus has two horns (uterus bicornis).[35]

Other

The number of

Secretory glands in the skin are present in virtually all species and can be located in different places, such as in the eyes, behind the horns, the neck, or back, on the feet, or in the anal region.

Artiodactyls have a

Lifestyle

Distribution and habitat

Artiodactyls are native to almost all parts of the world, with the exception of Oceania and Antarctica. Humans have introduced different artiodactyls worldwide as hunting animals.[40] Artiodactyls inhabit almost every habitat, from tropical rainforests and steppes to deserts and high mountain regions. The greatest biodiversity prevails in open habitats such as grasslands and open forests.

Social behavior

The social behavior of even-toed ungulates varies from species to species. Generally, there is a tendency to merge into larger groups, but some live alone or in pairs. Species living in groups often have a

Many artiodactyls are territorial and mark their territory, for example, with glandular secretions or urine. In addition to year-round sedentary species, there are animals that migrate seasonally.

There are

Reproduction and life expectancy

Generally, even-toed ungulates tend to have long

The length of the gestation period varies from four to five months for porcine, deer, and musk deer; six to ten months for hippos, deer, and bovines; ten to thirteen months with camels; and fourteen to fifteen months with giraffes. Most deliver one or two babies, but some pigs can deliver up to ten.

The newborns are

Life expectancy is typically twenty to thirty years; as in many mammals, smaller species often have a shorter lifespan than larger species. The artiodactyls with the longest lifespans are the hippos, cows, and camels, which can live 40 to 50 years.

Predators and parasites

Artiodactyls have different

Interactions with humans

Domestication

Artiodactyls have been hunted by primitive humans for various reasons: for meat or

Today, artiodactyls are kept primarily for their meat, milk, and wool, fur, or hide for clothing. Domestic cattle, the water buffalo, the yak, and camels are used for work, as rides, or as pack animals.[44][page needed]

Threats

The endangerment level of each even-toed ungulate is different. Some species are

Conversely, many artiodactyls have declined significantly in numbers, and some have even gone extinct, largely due to

See also

References

- S2CID 2010691.

- ^ ISBN 9780801887352.

- S2CID 134967454.

- ^ PMID 19774069.

- ^ PMID 9159933.

- ISBN 978-1-4214-0093-8.

- ^ Graur, Dan; Higgins, Desmond G. (1994). "Molecular Evidence for the Inclusion of Cetaceans within the Order Artiodactyla" (PDF). Molecular Biology and Evolution: 357–364. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 23 August 2015.

- PMID 8752004.

- S2CID 4429657.

- PMID 9159931.

- ^ PMID 18590827.

- PMID 12078645.

- PMID 12446807.

- PMID 12878460.

- ISBN 978-0-8160-1194-0.

- ^ S2CID 45056197.

- ^ Owen, Richard (1848). "Description of Teeth and portions of Jaws of two extinct Anthracotherioid Quadrupeds (Hyopotamus vectianus and Hyop. bovinus) discovered by the Marchioness of Hastings in the Eocene Deposits on the N.W. coast of the Isle of Wight: with an attempt to develope Cuvier's idea of the Classification of Pachyderms by the Number of their Toes". Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London. 4 (1): 103–141. Retrieved 16 February 2024.

- ^ etwa noch bei Nowak (1999) oder Hendrichs (2004)

- ISBN 978-0-231-11013-6.

- PMID 17101039.

- S2CID 206544776.

- PMID 22930817.

- PMID 22628470.

- PMID 31800571.(see e.g. Fig S10)

- ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0.

- PMID 17640355.

- ^ "Claws Out: Things You Didn't Know About Claws". Thomson Safaris. 7 January 2014. Retrieved 24 September 2016.

- ISBN 978-3-8304-1075-1.

- PMID 24148672.

- hdl:2246/5180. Archived from the originalon 6 October 2014. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-87196-871-5.

- ^ JSTOR 3801702.

- ^ a b c "Artiodactyl". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 2008. Retrieved 17 October 2008.

- ISBN 9781482295986.

- ^ ISBN 978-3-8304-1075-1.

- ^ Spinage, C. A. "Reproduction in the Uganda defassa waterbuck, Kobus defassa ugandae Neumann." Journal of reproduction and fertility 18.3 (1969): 445-457.

- ^ Yong, Hwan-Yul. "Reproductive System of Giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis). Archived 25 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine" Journal of Embryo Transfer 24.4 (2009): 293-295.

- ^ Sumar, Julio. "Reproductive physiology in South American Camelids." Genetics of Reproduction in Sheep (2013): 81.

- PMID 18426746.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-13-127836-3.

- ^ "Killer Whale". NOAA Fisheries. 3 August 2021. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- ^ McKie, Robin (22 September 2012). "Humans hunted for meat 2 million years ago". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- ^ "Bones From French Cave Show Neanderthals, Cro-Magnon Hunted Same Prey". ScienceDaily. 2003. Retrieved 17 October 2008.

- ISBN 978-1-55963-370-3.

- ^ "Cetartiodactyla". Retrieved 12 March 2007.

- ^ "Artiodactyla". Encyclopedia of Life. Retrieved 15 November 2014.