Ascalon

𐤀𐤔𐤒𐤋𐤍 אַשְׁקְלוֹן Ἀσκάλων عَسْقَلَان | |

Crusaders | |

| Site notes | |

|---|---|

| Excavation dates | 1815, 1920-1922, 1985-2016 |

| Archaeologists | Lady Hester Stanhope, John Garstang, W. J. Phythian-Adams, Lawrence Stager, Daniel Master |

Ascalon (

The site of Ascalon was first permanently settled in the

The ancient and

The modern Israeli city of Ashkelon takes its name from the site, and was established at the site of al-Majdal, the later town established to the northeast during the Mamluk period.

Names

Ascalon has been known by many variations of the same basic name over the millennia. The settlement is first mentioned in the

In the

History

Neolithic period

About 1.5 kilometres (1 mi) north of the ruins of Ascalon lies a

Canaanite settlement

The first constructed settlement was hewn into the sandstone outcrop along the coast in the Middle Bronze Age (2000–1550 BCE). A relatively large and thriving settlement for the period, its walls enclosed 60 hectares (150 acres) and as many as 15,000 people may have lived within these fortifications.

Its commanding ramparts measured 2.5 kilometres (1+1⁄2 mi) long, 15 m (50 ft) high and 45 m (150 ft) thick,[citation needed] and even as a ruin they stand two stories high. The thickness of the walls was so great that the mudbrick city gate had a stone-lined, 2.4-metre-wide (8 ft) tunnel-like barrel vault, coated with white plaster, to support the superstructure: it is the oldest such vault ever found.[9]

In the early MB IIA, the Egyptians mainly sent their ships further north to Lebanon (

Ascalon is mentioned in the

Egyptian period

Beginning in the time of Thutmose III (1479-1425 BC) the city was under Egyptian control, administered by a local governor. In the Amarna letters (c. 1350 BC), there are seven letters to and from King Yidya of Ašqaluna and the Egyptian pharaoh.

During the reign of Ramesses II the Southern Levant was the frontier of the epic war against the Hittites in Syria. In addition, the Sea Peoples attacked and rebellions occurred. These events coincide with a downturn in climatic conditions starting around 1250 BC onwards, ultimately causing the Late Bronze Age collapse. On the death of Ramesses II, turmoil and rebellion increased in the Southern Levant. The king Merneptah faced a series of uprisings, as told in the Merneptah Stele. The Pharaoh notes putting down a rebellion at "'Asqaluni".[3] Further north, the King Jabin of Hazor tried to fight for independence with Mycenaean mercenaries—Merneptah laying waste the grain fields in the Valley of Yizreel to starve out the northern rebellion. These events contributed to the fall of the 19th dynasty.[citation needed]

Philistine settlement

The Philistines conquered the Canaanite city in about 1150 BCE. Their earliest pottery, types of structures and inscriptions are similar to the early Greek urbanised centre at

In this period, the Hebrew Bible presents Ašqəlôn as one of the five Philistine cities that are constantly warring with the Israelites. According to Herodotus, the city's temple of Aphrodite (Derketo) was the oldest of its kind, imitated even in Cyprus, and he mentions that this temple was pillaged by marauding Scythians during the time of their sway over the Medes (653–625 BCE). It was the last of the Philistine cities to hold out against Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II. When it fell in 604 BCE, burnt and destroyed and its people taken into exile, the Philistine era was over.[citation needed]

Persian, Hellenistic and Roman periods

Until the conquest of

During the Persian period, the city was probably in

After the conquest of Alexander in the 4th century BCE, Ashkelon was an important free city and

It had mostly friendly relations with the

Roman and Islamic era fortifications, faced with stone, followed the same footprint as the earlier Canaanite settlement, forming a vast semicircle protecting the settlement on the land side. On the sea it was defended by a high natural bluff. A roadway more than six metres (20 ft) in width ascended the rampart from the harbor and entered a gate at the top.

The city remained loyal to Rome during the Great Revolt, 66–70 CE.

Byzantine period

The city of Ascalon appears on a fragment of the 6th-century Madaba Map.[16]

The bishops of Ascalon whose names are known include Sabinus, who was at the

No longer a residential bishopric, Ascalon is today listed by the Catholic Church as a titular see.[19]

Early Islamic period

During the

Asqalan prospered under the

Shrine of Husayn's Head

In 1091, a couple of years after a campaign by grand vizier Badr al-Jamali to reestablish Fatimid control over the region, the head of Husayn ibn Ali (a grandson of the Islamic prophet Muhammad) was "rediscovered", prompting Badr to order the construction of a new mosque and mashhad (shrine or mausoleum) to hold the relic, known as the Shrine of Husayn's Head.[21][22][23] According to another source, the shrine was built in 1098 by the Fatimid vizier al-Afdal Shahanshah.[24][verification needed]

The mausoleum was described as the most magnificent building in Asqalan.

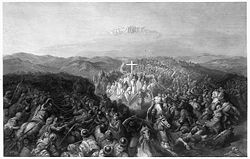

Crusaders, Ayyubids, and Mamluks

During the Crusades, Asqalan (known to the Crusaders as Ascalon) was an important city due to its location near the coast and between the Crusader States and Egypt. In 1099, shortly after the Siege of Jerusalem, a Fatimid army that had been sent to relieve Jerusalem was defeated by a Crusader force at the Battle of Ascalon. The city itself was not captured by the Crusaders because of internal disputes among their leaders. This battle is widely considered to have signified the end of the First Crusade.[citation needed] As a result of military reinforcements from Egypt and a large influx of refugees from areas conquered by the Crusaders, Asqalan became a major Fatimid frontier post.[24] The Fatimids utilized it to launch raids into the Kingdom of Jerusalem.[31] Trade ultimately resumed between Asqalan and Crusader-controlled Jerusalem, though the inhabitants of Asqalan regularly struggled with shortages in food and supplies, necessitating the provision of goods and relief troops to the city from Egypt on several occasions each year.[24] According to William of Tyre, the entire civilian population of the city was included in the Fatimid army registers.[24] The Crusaders' capture of the port city of Tyre in 1134 and their construction of a ring of fortresses around the city to neutralize its threat to Jerusalem strategically weakened Asqalan.[24] In 1150 the Fatimids fortified the city with fifty-three towers, as it was their most important frontier fortress.[32]

Three years later, after a seven-month siege, the city was captured by a Crusader army led by King Baldwin III of Jerusalem.[24] Ibn al-Qalanisi recorded that upon the city's surrender, all Muslims with the means to do so emigrated from the city.[33] The Fatimids secured the head of Husayn from its mausoleum outside the city and transported it to their capital Cairo.[24] Ascalon was then added to the County of Jaffa to form the County of Jaffa and Ascalon, which became one of the four major seigneuries of the Kingdom of Jerusalem.

After the Crusader conquest of Jerusalem the six elders of the Karaite Jewish community in Ascalon contributed to the ransoming of captured Jews and holy relics from Jerusalem's new rulers. The Letter of the Karaite elders of Ascalon, which was sent to the Jewish elders of Alexandria, describes their participation in the ransom effort and the ordeals suffered by many of the freed captives. A few hundred Jews, Karaites and Rabbanites, were living in Ascalon in the second half of the 12th century, but moved to Jerusalem when the city was destroyed in 1191.[34]

In 1187,

The ancient and medieval history of Ascalon was brought to an end in 1270, when the then Mamluk sultan Baybars ordered the citadel and harbour at the site to be destroyed as part of a wider decision to destroy the Levantine coastal towns in order to forestall future Crusader invasions. Some monuments, like the shrine of Sittna Khadra and Shrine of Husayn's Head survived. According to Marom and Taxel, this event irreversibly changed the settlement patterns in the region. As a substitute for ‘Asqalān, Baybars established Majdal ‘Asqalān, 3 km inland, and endowed it with a magnificent Friday Mosque, a marketplace and religious shrines.[35]

Archaeology

Beginning in the 18th century, the site was visited, and occasionally drawn, by a number of adventurers and tourists. It was also often scavenged for building materials. The first known excavation occurred in 1815. The Lady Hester Stanhope dug there for two weeks using 150 workers. No real records were kept.[36] In the 1800s some classical pieces from Ascalon (though long thought to be from Thessaloniki) were sent to the Ottoman Museum.[37] From 1920 to 1922 John Garstang and W. J. Phythian-Adams excavated on behalf of the Palestine Exploration Fund. They focused on two areas, one Roman and the other Philistine/Canaanite.[38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45] Over the following years a number of salvage excavations were carried out by the Israel Antiquities Authority.[46]

In 1954 by French archaeologist

Modern excavation began in 1985 with the Leon Levy Expedition. Between then and 2006 seventeen seasons of work occurred, led by Lawrence Stager of Harvard University.[47][48][49][50][51][52][53] In 2007 the next phase of excavation began under Daniel Master. It continued until 2016.

In 1991 the ruins of a small ceramic tabernacle was found a finely cast bronze statuette of a bull calf, originally silvered, ten centimetres (4 in) long. Images of calves and bulls were associated with the worship of the Canaanite gods El and Baal.

In the 1997 season a cuneiform table fragment was found, being a lexical list containing both Sumerian and Canaanite language columns. It was found in a Late Bronze Age II context, about 13th century BC.[54]

In 2012 an Iron Age IIA Philistine cemetery was discovered outside the city. In 2013 200 graves were excavated of the estimated 1,200 the cemetery contained. Seven were stone built tombs.[55]

One ostracon and 18 jar handles were recovered inscribed with the

Notable people

- Antiochus of Ascalon (125–68 BC), Platonic philosopher

- Ibn Hajar al-Asqalani (1372–1449), Islamic hadith scholar

See also

- List of cities of the ancient Near East

- Im schwarzen Walfisch zu Askalon, song

- Scallion and shallot, types of onion known from and named after ancient Ascalon - Ascalōnia caepa or Ascalonian onion[57]

References

- ^ JSTOR 26751887.

- ^ Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 150. Quoted in Khalidi, 1992, p. 116

- ^ JSTOR 27926029.

- ^ "Ascalon". Oxford Reference.

- .

- JSTOR 991676.

- .

- ^ a b c d e f g h Hartmann & Lewis 1960, p. 710.

- ^ a b Lefkovits, Etgar (8 April 2008). "Oldest arched gate in the world restored". The Jerusalem Post. Jerusalem. Archived from the original on 14 August 2013. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- ^ M. Stern, Greek and Latin Authors on Jews and Judaism, Vol. III: III. Pseudo-Scylax

- ^ Andrea M. Berlin, Archaeological Sources for the History of Palestine: Between Large Forces: Palestine in the Hellenistic Period, The Biblical Archaeologist 60, 1997, p 42 doi: 10.2307/3210581

- Sanhedrin, 6:6.

- ^ "Ashkelon". Project on Ancient Cultural Engagement/Brill. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- ^ Negev, A (1976). Stillwell, Richard.; MacDonald, William L.; McAlister, Marian Holland (eds.). The Princeton encyclopedia of classical sites. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Eusebius (1890). "VI". In McGiffert, Arthur Cushman (ed.). The Church History of Eusebius. Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, series II. §2, notes 90-91.

- ISBN 978-90-3900011-3. quoted in The Madaba Mosaic Map: Ascalon

- ^ Bagatti, Ancient Christian Villages of Judaea and Negev, quoted in The Madaba Mosaic Map: Ascalon

- ^ Pius Bonifacius Gams, Series episcoporum Ecclesiae Catholicae, Leipzig 1931, p. 452

- ISBN 978-88-209-9070-1), p. 840

- ^ Lecker 1989, p. 35, note 109.

- ISBN 9781474421522.

- S2CID 240874864.

- ISBN 9780195309911.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hartmann & Lewis 1960, p. 711.

- ISBN 0-521-59984-9.

- ^ Canaan, 1927, p. 151

- ^ Meron Rapoport, 'History Erased,' Haaretz, 5 July 2007.

- ^ Talmon-Heller, Kedar & Reiter 2016.

- ^ Petersen 2017, p. 108.

- doi:10.1515/islam-2016-0008. Archived from the originalon 12 May 2020.

- ^ Hartmann & Lewis 1960, pp. 710–711.

- ^ Gore, Rick (January 2001). "Ancient Ashkelon". National Geographic. Archived from the original on March 26, 2008.

- ^ Benjamin Z. Kedar. “Subjected Muslims of the Frankish Levant.” In James M. Powell, editor. Muslims under Latin Rule, 1100-1300. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1985. p. 150

- ISBN 3-88226-479-9.

- ISSN 0305-7488.

- ^ Charles L. Meryon, Travels of Lady Hester Stanhope. 3 vols. London: Henry Colburn, 1846

- S2CID 164821955.

- ^ Garstang, John (1921). "The Fund's Excavation of Ashkalon". PEFQS. 53: 12–16.

- ^ John Garstang, "The Fund's Excavation of Askalon, 1920-1921", PEFQS, vol. 53, pp. 73–75, 1921

- ^ John Garstang, "Askalon Reports: The Philistine Problem", PEFQS, vol. 53, pp. 162–63, 1921

- ^ John Garstang, "The Excavations at Ashkalon", PEFQS, vol. 54, pp. 112–19, 1922

- ^ John Garstang, "Ashkalon", PEFQS, vol. 56, pp. 24–35, 1924

- ^ W. J. Phythian-Adams, "History of Askalon", PEFQS, vol. 53, pp. 76–90, 1921

- ^ W. J. Phythian-Adams, "Askalon Reports: Stratigraphical Sections", PEFQS, vol. 53, pp. 163–69, 1921

- ^ W. J. Phythian-Adams, "Report on the Stratification of Askalon", PEFQS, vol. 55, pp. 60–84, 1923

- ^ [1] Yaakov Huster, Daniel M. Master, and Michael D. Press, "Ashkelon 5 The Land behind Ashkelon", Eisenbrauns, 2015 ISBN 978-1-57506-952-4

- ^ [2] Daniel M. Master, J. David Schloen, and Lawrence E. Stager, "Ashkelon 1 Introduction and Overview (1985-2006)", Eisenbrauns, 2008 ISBN 978-1-57506-929-6

- ^ [3] Barbara L. Johnson, "Ashkelon 2 Imported Pottery of the Roman and Late Roman Periods", Eisenbrauns, 2008 ISBN 978-1-57506-930-2

- ^ [4] Daniel M. Master, J. David Schloen, and Lawrence E. Stager, "Ashkelon 3 The Seventh Century B.C.", Eisenbrauns, 2011 ISBN 978-1-57506-939-5

- ^ [5] Michael D. Press, "Ashkelon 4 The Iron Age Figurines of Ashkelon and Philistia", Eisenbrauns, 2012 ISBN 978-1-57506-942-5

- ^ Lawrence E. Stager, J. David Schloen, and Ross J. Voss, "Ashkelon 6 The Middle Bronze Age Ramparts and Gates of the North Slope and Later Fortifications", Eisenbrauns, 2018 ISBN 978-1-57506-980-7

- ^ Lawrence E. Stager, Daniel M. Master, and Adam J. Aja, "Ashkelon 7 The Iron Age I", Eisenbrauns, 2020 ISBN 978-1-64602-090-4

- ^ Tracy Hoffman, "Ashkelon 8 The Islamic and Crusader Periods", Eisenbrauns, 2019 ISBN 978-1-57506-735-3

- JSTOR 27926892.

- S2CID 164842977.

- JSTOR 27927139.

- ^ "scallion", at Balashon - Hebrew Language Detective, 5 July 2006. Accessed 28 Feb 2024.

Sources

- Hartmann, R. & OCLC 495469456.

- "Ashkelon Excavations - The Leon Levy Expedition". Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures. The University of Chicago. Retrieved 5 January 2024.

- ISBN 0-88728-224-5.

- Lecker, Michael (1989). "The Estates of 'Amr b. al-'Āṣ in Palestine: Notes on a New Negev Arabic Inscription". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. 52 (1): 24–37. S2CID 163092638.

- Petersen, A. (2017). "Shrine of Husayn's Head". Bones of Contention: Muslim Shrines in Palestine. Heritage Studies in the Muslim World. Springer Singapore. ISBN 978-981-10-6965-9. Retrieved 2023-01-06.