Asthma

| Asthma | |

|---|---|

chest tightness, shortness of breath[4] | |

| Complications | Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), sinusitis, obstructive sleep apnea |

| Usual onset | Childhood |

| Duration | Long term[5] |

| Causes | Genetic and environmental factors[4] |

| Risk factors | Air pollution, allergens[5] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, response to therapy, spirometry[6] |

| Treatment | Avoiding triggers, inhaled corticosteroids, salbutamol[7][8] |

| Frequency | approx. 262 million (2019)[9] |

| Deaths | approx. 461,000 (2019)[9] |

Asthma is a

Asthma is thought to be caused by a combination of

There is no known cure for asthma, but it can be controlled.

In 2019 asthma affected approximately 262 million people and caused approximately 461,000 deaths.

Signs and symptoms

Asthma is characterized by recurrent episodes of

Associated conditions

A number of other health conditions occur more frequently in people with asthma, including

Cavities occur more often in people with asthma.[36] This may be related to the effect of beta2-adrenergic agonists decreasing saliva.[37] These medications may also increase the risk of dental erosions.[37]

Causes

Asthma is caused by a combination of complex and incompletely understood environmental and genetic interactions.

Environmental

Many environmental factors have been associated with asthma's development and exacerbation, including allergens, air pollution, and other environmental chemicals.

Exposure to indoor

The majority of the evidence does not support a causal role between paracetamol (acetaminophen) or antibiotic use and asthma.[57][58] A 2014 systematic review found that the association between paracetamol use and asthma disappeared when respiratory infections were taken into account.[59] Maternal psychological stress during pregnancy is a risk factor for the child to develop asthma.[60]

Asthma is associated with exposure to indoor allergens.

Hygiene hypothesis

The

Use of antibiotics in early life has been linked to the development of asthma.[72] Also, delivery via caesarean section is associated with an increased risk (estimated at 20–80%) of asthma – this increased risk is attributed to the lack of healthy bacterial colonization that the newborn would have acquired from passage through the birth canal.[73][74] There is a link between asthma and the degree of affluence which may be related to the hygiene hypothesis as less affluent individuals often have more exposure to bacteria and viruses.[75]

Genetic

| Endotoxin levels | CC genotype | TT genotype |

|---|---|---|

| High exposure | Low risk | High risk |

| Low exposure | High risk | Low risk |

Family history is a risk factor for asthma, with many different genes being implicated.

Some genetic variants may only cause asthma when they are combined with specific environmental exposures.

Medical conditions

A triad of

There is a correlation between obesity and the risk of asthma with both having increased in recent years.[83][84] Several factors may be at play including decreased respiratory function due to a buildup of fat and the fact that adipose tissue leads to a pro-inflammatory state.[85]

Exacerbation

Some individuals will have stable asthma for weeks or months and then suddenly develop an episode of acute asthma. Different individuals react to various factors in different ways.[91] Most individuals can develop severe exacerbation from a number of triggering agents.[91]

Home factors that can lead to exacerbation of asthma include

Asthma exacerbations in school‐aged children peak in autumn, shortly after children return to school. This might reflect a combination of factors, including poor treatment adherence, increased allergen and viral exposure, and altered immune tolerance. There is limited evidence to guide possible approaches to reducing autumn exacerbations, but while costly, seasonal omalizumab treatment from four to six weeks before school return may reduce autumn asthma exacerbations.[94]

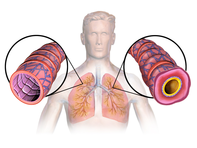

Pathophysiology

Asthma is the result of chronic

Diagnosis

While asthma is a well-recognized condition, there is not one universal agreed upon definition.[21] It is defined by the Global Initiative for Asthma as "a chronic inflammatory disorder of the airways in which many cells and cellular elements play a role. The chronic inflammation is associated with airway hyper-responsiveness that leads to recurrent episodes of wheezing, breathlessness, chest tightness and coughing particularly at night or in the early morning. These episodes are usually associated with widespread but variable airflow obstruction within the lung that is often reversible either spontaneously or with treatment".[22]

There is currently no precise test for the diagnosis, which is typically based on the pattern of symptoms and response to therapy over time.[6][21] Asthma may be suspected if there is a history of recurrent wheezing, coughing or difficulty breathing and these symptoms occur or worsen due to exercise, viral infections, allergens or air pollution.[95] Spirometry is then used to confirm the diagnosis.[95] In children under the age of six the diagnosis is more difficult as they are too young for spirometry.[96]

Spirometry

Others

The

Other supportive evidence includes: a ≥20% difference in

Classification

| Severity | Symptom frequency | Night-time symptoms | %FEV1 of predicted | FEV1 variability | SABA use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intermittent | ≤2/week | ≤2/month | ≥80% | <20% | ≤2 days/week |

| Mild persistent | >2/week | 3–4/month | ≥80% | 20–30% | >2 days/week |

| Moderate persistent | Daily | >1/week | 60–80% | >30% | daily |

| Severe persistent | Continuously | Frequent (7/week) | <60% | >30% | ≥twice/day |

Asthma is clinically classified according to the frequency of symptoms, forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), and

Although asthma is a chronic

Asthma exacerbation

| Near-fatal | High PaCO2 , or requiring mechanical ventilation, or both

| |

|---|---|---|

| Life-threatening (any one of) | ||

| Clinical signs | Measurements | |

| Altered level of consciousness

|

Peak flow < 33%

| |

| Exhaustion | Oxygen saturation < 92% | |

Arrhythmia

|

PaO2 < 8 kPa

| |

| Low blood pressure | "Normal" PaCO2 | |

| Cyanosis | ||

| Silent chest | ||

| Poor respiratory effort | ||

| Acute severe (any one of) | ||

| Peak flow 33–50% | ||

| Respiratory rate ≥ 25 breaths per minute | ||

| Heart rate ≥ 110 beats per minute | ||

| Unable to complete sentences in one breath | ||

| Moderate | Worsening symptoms | |

| Peak flow 50–80% best or predicted | ||

| No features of acute severe asthma | ||

An acute asthma exacerbation is commonly referred to as an asthma attack. The classic symptoms are

Signs occurring during an asthma attack include the use of accessory

In a mild exacerbation the

Acute severe asthma, previously known as status asthmaticus, is an acute exacerbation of asthma that does not respond to standard treatments of bronchodilators and corticosteroids.[116] Half of cases are due to infections with others caused by allergen, air pollution, or insufficient or inappropriate medication use.[116]

Brittle asthma is a kind of asthma distinguishable by recurrent, severe attacks.[109] Type 1 brittle asthma is a disease with wide peak flow variability, despite intense medication. Type 2 brittle asthma is background well-controlled asthma with sudden severe exacerbations.[109]

Exercise-induced

Exercise can trigger bronchoconstriction both in people with or without asthma.[117] It occurs in most people with asthma and up to 20% of people without asthma.[117] Exercise-induced bronchoconstriction is common in professional athletes. The highest rates are among cyclists (up to 45%), swimmers, and cross-country skiers.[118] While it may occur with any weather conditions, it is more common when it is dry and cold.[119] Inhaled beta2 agonists do not appear to improve athletic performance among those without asthma;[120] however, oral doses may improve endurance and strength.[121][122]

Occupational

Asthma as a result of (or worsened by) workplace exposures is a commonly reported

Aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease

Alcohol-induced asthma

Alcohol may worsen asthmatic symptoms in up to a third of people.[129] This may be even more common in some ethnic groups such as the Japanese and those with aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease.[129] Other studies have found improvement in asthmatic symptoms from alcohol.[129]

Non-atopic asthma

Non-atopic asthma, also known as intrinsic or non-allergic, makes up between 10 and 33% of cases. There is negative skin test to common inhalant allergens. Often it starts later in life, and women are more commonly affected than men. Usual treatments may not work as well.[130] The concept that "non-atopic" is synonymous with "non-allergic" is called into question by epidemiological data that the prevalence of asthma is closely related to the serum IgE level standardized for age and sex (P<0.0001), indicating that asthma is almost always associated with some sort of IgE-related reaction and therefore has an allergic basis, although not all the allergic stimuli that cause asthma appear to have been included in the battery of aeroallergens studied (the "missing antigen(s)" hypothesis).[131] For example, an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of population-attributable risk (PAR) of Chlamydia pneumoniae biomarkers in chronic asthma found that the PAR for C. pneumoniae-specific IgE was 47%.[132]

Infectious asthma

Infectious asthma is an easily identified clinical presentation.[133] When queried, asthma patients may report that their first asthma symptoms began after an acute lower respiratory tract illness. This type of history has been labelled the "infectious asthma" (IA) syndrome,[134] or as "asthma associated with infection" (AAWI)[135] to distinguish infection-associated asthma initiation from the well known association of respiratory infections with asthma exacerbations. Reported clinical prevalences of IA for adults range from around 40% in a primary care practice[134] to 70% in a specialty practice treating mainly severe asthma patients.[136] Additional information on the clinical prevalence of IA in adult-onset asthma is unavailable because clinicians are not trained to elicit this type of history routinely, and recollection in child-onset asthma is challenging. A population-based incident case-control study in a geographically defined area of Finland reported that 35.8% of new-onset asthma cases had experienced acute bronchitis or pneumonia in the year preceding asthma onset, representing a significantly higher risk compared to randomly selected controls (Odds ratio 7.2, 95% confidence interval 5.2-10).[137]

Phenotyping and endotyping

Asthma phenotyping and endotyping has emerged as a novel approach to asthma classification inspired by precision medicine which separates the clinical presentations of asthma, or asthma phenotypes, from their underlying causes, or asthma endotypes. The best-supported endotypic distinction is the type 2-high/type 2-low distinction. Classification based on type 2 inflammation is useful in predicting which patients will benefit from targeted biologic therapy.[138][139]

Differential diagnosis

Many other conditions can cause symptoms similar to those of asthma. In children, symptoms may be due to other upper airway diseases such as

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease can coexist with asthma and can occur as a complication of chronic asthma. After the age of 65, most people with obstructive airway disease will have asthma and COPD. In this setting, COPD can be differentiated by increased airway neutrophils, abnormally increased wall thickness, and increased smooth muscle in the bronchi. However, this level of investigation is not performed due to COPD and asthma sharing similar principles of management: corticosteroids, long-acting beta-agonists, and smoking cessation.[143] It closely resembles asthma in symptoms, is correlated with more exposure to cigarette smoke, an older age, less symptom reversibility after bronchodilator administration, and decreased likelihood of family history of atopy.[144][145]

Prevention

The evidence for the effectiveness of measures to prevent the development of asthma is weak.

Early pet exposure may be useful.[149] Results from exposure to pets at other times are inconclusive[150] and it is only recommended that pets be removed from the home if a person has allergic symptoms to said pet.[151]

Dietary restrictions during pregnancy or when breastfeeding have not been found to be effective at preventing asthma in children and are not recommended.[151] Omega-3 consumption, mediterranean diet and anti-oxidants have been suggested by some studies that might help preventing crisis but the evidence is still inconclusive.[152]

Reducing or eliminating compounds known to sensitive people from the work place may be effective.

Management

While there is no cure for asthma, symptoms can typically be improved.

People with asthma have higher rates of anxiety, psychological stress, and depression.[167][168] This is associated with poorer asthma control.[167] Cognitive behavioral therapy may improve quality of life, asthma control, and anxiety levels in people with asthma.[167]

Improving people's knowledge about asthma and using a written action plan has been identified as an important component of managing asthma.[169] Providing educational sessions that include information specific to a person's culture is likely effective.[170] More research is necessary to determine if increasing preparedness and knowledge of asthma among school staff and families using home-based and school interventions results in long term improvements in safety for children with asthma.[171][172][173] School-based asthma self-management interventions, which attempt to improve knowledge of asthma, its triggers and the importance of regular practitioner review, may reduce hospital admissions and emergency department visits. These interventions may also reduce the number of days children experience asthma symptoms and may lead to small improvements in asthma-related quality of life.[174] More research is necessary to determine if shared-decision-making is helpful for managing adults with asthma[175] or if a personalized asthma action plan is effective and necessary.[176] Some people with asthma use pulse oximeters to monitor their own blood oxygen levels during an asthma attack. However, there is no evidence regarding the use in these instances.[177]

Lifestyle modification

Avoidance of triggers is a key component of improving control and preventing attacks. The most common triggers include

Overall, exercise is beneficial in people with stable asthma.[182] Yoga could provide small improvements in quality of life and symptoms in people with asthma.[183] More research is necessary to determine how effective weight loss is on improving quality of life, the usage of health care services, and adverse effects for people of all ages with asthma.[184][185]

Medications

Medications used to treat asthma are divided into two general classes: quick-relief medications used to treat acute symptoms; and long-term control medications used to prevent further exacerbation.[157] Antibiotics are generally not needed for sudden worsening of symptoms or for treating asthma at any time.[186][187]

Medications for asthma exacerbations

- Short-acting beta2-adrenoceptor agonists (SABA), such as salbutamol (albuterol USAN) are the first line treatment for asthma symptoms.[8] They are recommended before exercise in those with exercise induced symptoms.[188]

- ipratropium, provide additional benefit when used in combination with SABA in those with moderate or severe symptoms and may prevent hospitalizations.[8][189][190] Anticholinergic bronchodilators can also be used if a person cannot tolerate a SABA.[105] If a child requires admission to hospital additional ipratropium does not appear to help over a SABA.[191] For children over 2 years old with acute asthma symptoms, inhaled anticholinergic medications taken alone is safe but is not as effective as inhaled SABA or SABA combined with inhaled anticholinergic medication.[192][189] Adults who receive combined inhaled medications that includes short-acting anticholinergics and SABA may be at risk for increased adverse effects such as experiencing a tremor, agitation, and heart beat palpitations compared to people who are treated with SABA by itself.[190]

- Older, less selective adrenergic agonists, such as inhaled epinephrine, have similar efficacy to SABAs.[193] They are however not recommended due to concerns regarding excessive cardiac stimulation.[194]

- Corticosteroids can also help with the acute phase of an exacerbation because of their antiinflamatory properties. The benefit of systemic and oral corticosteroids is well established. Inhaled or nebulized corticosteroids can also be used.[152] For adults and children who are in the hospital due to acute asthma, systemic (IV) corticosteroids improve symptoms.[195][196] A short course of corticosteroids after an acute asthma exacerbation may help prevent relapses and reduce hospitalizations.[197]

- Other remedies, less established, are intravenous or nebulized magnesium sulfate and helium mixed with oxygen. Aminophylline could be used with caution as well.[152]

- Mechanical ventilation is the last resort in case of severe hypoxemia.[152]

- Intravenous administration of the drug aminophylline does not provide an improvement in bronchodilation when compared to standard inhaled beta-2 agonist treatment.[198] Aminophylline treatment is associated with more adverse effects compared to inhaled beta-2 agonist treatment.[198]

Long–term control

- Corticosteroids are generally considered the most effective treatment available for long-term control.[157] Inhaled forms are usually used except in the case of severe persistent disease, in which oral corticosteroids may be needed.[157] Dosage depends on the severity of symptoms.[199] High dosage and long term use might lead to the appearance of common adverse effects which are growth delay, adrenal suppression, and osteoporosis.[152] Continuous (daily) use of an inhaled corticosteroid, rather than its intermitted use, seems to provide better results in controlling asthma exacerbations.[152] Commonly used corticosteroids are budesonide, fluticasone, mometasone and ciclesonide.[152]

- side-effects,[203] and with corticosteroids they may slightly increase the risk.[204][205] Evidence suggests that for children who have persistent asthma, a treatment regime that includes LABA added to inhaled corticosteroids may improve lung function but does not reduce the amount of serious exacerbations.[206] Children who require LABA as part of their asthma treatment may need to go to the hospital more frequently.[206]

- Leukotriene receptor antagonists (anti-leukotriene agents such as montelukast and zafirlukast) may be used in addition to inhaled corticosteroids, typically also in conjunction with a LABA.[17][207][208][209] For adults or adolescents who have persistent asthma that is not controlled very well, the addition of anti-leukotriene agents along with daily inhaled corticosteriods improves lung function and reduces the risk of moderate and severe asthma exacerbations.[208] Anti-leukotriene agents may be effective alone for adolescents and adults; however, there is no clear research suggesting which people with asthma would benefit from anti-leukotriene receptor alone.[210] In those under five years of age, anti-leukotriene agents were the preferred add-on therapy after inhaled corticosteroids.[152][211] A 2013 Cochrane systematic review concluded that anti-leukotriene agents appear to be of little benefit when added to inhaled steroids for treating children.[212] A similar class of drugs, 5-LOX inhibitors, may be used as an alternative in the chronic treatment of mild to moderate asthma among older children and adults.[17][213] As of 2013[update] there is one medication in this family known as zileuton.[17]

- Oral Theophyllines are sometimes used for controlling chronic asthma, but their used is minimized because of their side effects.[152]

- Omalizumab, a monoclonal Antibody Against IgE, is a novel way to lessen exacerbations by decreasing the levels of circulating IgE that play a significant role at allergic asthma.[152][214]

- Anticholinergic medications such as ipratropium bromide have not been shown to be beneficial for treating chronic asthma in children over 2 years old,[215] but is not suggested for routine treatment of chronic asthma in adults.[216]

- There is no strong evidence to recommend chloroquine medication as a replacement for taking corticosteroids by mouth (for those who are not able to tolerate inhaled steroids).[217] Methotrexate is not suggested as a replacement for taking corticosteriods by mouth ("steroid sparing") due to the adverse effects associated with taking methotrexate and the minimal relief provided for asthma symptoms.[218]

- Macrolide antibiotics, particularly the azalide macrolide azithromycin, are a recently added GINA-recommended treatment option for both eosinophilic and non-eosinophilic severe, refractory asthma based on azithromycin's efficacy in reducing moderate and severe exacerbations combined.[219][220] Azithromycin's mechanism of action is not established, and could involve pathogen- and/or host-directed anti-inflammatory activities.[221] Limited clinical observations suggest that some patients with new-onset asthma and with "difficult-to-treat" asthma (including those with the asthma-COPD overlap syndrome - ACOS) may respond dramatically to azithromycin.[222][223] However, these groups of asthma patients have not been studied in randomized treatment trials and patient selection needs to be carefully individualized.

For children with asthma which is well-controlled on combination therapy of

Delivery methods

Medications are typically provided as

Adverse effects

Long-term use of inhaled corticosteroids at conventional doses carries a minor risk of adverse effects.

Others

Inflammation in the lungs can be estimated by the level of exhaled nitric oxide.[235][236] The use of exhaled nitric oxide levels (FeNO) to guide asthma medication dosing may have small benefits for preventing asthma attacks but the potential benefits are not strong enough for this approach to be universally recommended as a method to guide asthma therapy in adults or children.[235][236]

When asthma is unresponsive to usual medications, other options are available for both emergency management and prevention of flareups. Additional options include:

- Humidified hypoxia if saturations fall below 92%.[152]

- Corticosteroid by mouth are recommended with five days of prednisone being the same 2 days of dexamethasone.[237] One review recommended a seven-day course of steroids.[238]

- Magnesium sulfate intravenous treatment increases bronchodilation when used in addition to other treatment in moderate severe acute asthma attacks.[18][239][240] In adults intravenous treatment results in a reduction of hospital admissions.[241] Low levels of evidence suggest that inhaled (nebulised) magnesium sulfate may have a small benefit for treating acute asthma in adults.[242] Overall, high quality evidence do not indicate a large benefit for combining magnesium sulfate with standard inhaled treatments for adults with asthma.[242]

- Heliox, a mixture of helium and oxygen, may also be considered in severe unresponsive cases.[18]

- Intravenous salbutamol is not supported by available evidence and is thus used only in extreme cases.[243]

- Methylxanthines (such as theophylline) were once widely used, but do not add significantly to the effects of inhaled beta-agonists.[243] Their use in acute exacerbations is controversial.[244]

- The dissociative anesthetic ketamine is theoretically useful if intubation and mechanical ventilation is needed in people who are approaching respiratory arrest; however, there is no evidence from clinical trials to support this.[245] A 2012 Cochrane review found no significant benefit from the use of ketamine in severe acute asthma in children.[246]

- For those with severe persistent asthma not controlled by inhaled corticosteroids and LABAs, bronchial thermoplasty may be an option.[247] It involves the delivery of controlled thermal energy to the airway wall during a series of bronchoscopies.[247][248] While it may increase exacerbation frequency in the first few months it appears to decrease the subsequent rate. Effects beyond one year are unknown.[249]

- Monoclonal antibody injections such as mepolizumab,[250] dupilumab,[251] or omalizumab may be useful in those with poorly controlled atopic asthma.[252] However, as of 2019[update] these medications are expensive and their use is therefore reserved for those with severe symptoms to achieve cost-effectiveness.[253] Monoclonal antibodies targeting interleukin-5 (IL-5) or its receptor (IL-5R), including mepolizumab, reslizumab or benralizumab, in addition to standard care in severe asthma is effective in reducing the rate of asthma exacerbations. There is limited evidence for improved health-related quality of life and lung function.[254]

- Evidence suggests that sublingual immunotherapy in those with both allergic rhinitis and asthma improve outcomes.[255]

- It is unclear if non-invasive positive pressure ventilation in children is of use as it has not been sufficiently studied.[256]

Adherence to asthma treatments

Staying with a treatment approach for preventing asthma exacerbations can be challenging, especially if the person is required to take medicine or treatments daily.[257] Reasons for low adherence range from a conscious decision to not follow the suggested medical treatment regime for various reasons including avoiding potential side effects, misinformation, or other beliefs about the medication.[257] Problems accessing the treatment and problems administering the treatment effectively can also result in lower adherence. Various approaches have been undertaken to try and improve adherence to treatments to help people prevent serious asthma exacerbations including digital interventions.[257]

Alternative medicine

Many people with asthma, like those with other chronic disorders, use alternative treatments; surveys show that roughly 50% use some form of unconventional therapy.[258][259] There is little data to support the effectiveness of most of these therapies.

Evidence is insufficient to support the usage of vitamin C or vitamin E for controlling asthma.[260][261] There is tentative support for use of vitamin C in exercise induced bronchospasm.[262] Fish oil dietary supplements (marine n-3 fatty acids)[263] and reducing dietary sodium[264] do not appear to help improve asthma control. In people with mild to moderate asthma, treatment with vitamin D supplementation or its hydroxylated metabolites does not reduce acute exacerbations or improve control.[265] There is no strong evidence to suggest that vitamin D supplements improve day-to-day asthma symptoms or a person's lung function.[265] There is no strong evidence to suggest that adults with asthma should avoid foods that contain monosodium glutamate (MSG).[266] There have not been enough high-quality studies performed to determine if children with asthma should avoid eating food that contains MSG.[266]

Prognosis

The prognosis for asthma is generally good, especially for children with mild disease.[273] Mortality has decreased over the last few decades due to better recognition and improvement in care.[274] In 2010 the death rate was 170 per million for males and 90 per million for females.[275] Rates vary between countries by 100-fold.[275]

Globally it causes moderate or severe disability in 19.4 million people as of 2004[update] (16 million of which are in low and middle income countries).[276] Of asthma diagnosed during childhood, half of cases will no longer carry the diagnosis after a decade.[77] Airway remodeling is observed, but it is unknown whether these represent harmful or beneficial changes.[277] More recent data find that severe asthma can result in airway remodeling and the "asthma with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease syndrome (ACOS)" that has a poor prognosis.[278] Early treatment with corticosteroids seems to prevent or ameliorates a decline in lung function.[279] Asthma in children also has negative effects on quality of life of their parents.[280]

-

Asthma deaths per million persons in 20120–1011–1314–1718–2324–3233–4344–5051–6667–9596–251

-

Disability-adjusted life year for asthma per 100,000 inhabitants in 2004[281]no data0-100100–150150–200200–250250–300300–350350–400400–450450–500500–550550–600>600

Epidemiology

In 2019, approximately 262 million people worldwide were affected by asthma and approximately 461,000 people died from the disease.

While asthma is twice as common in boys as girls,[22] severe asthma occurs at equal rates.[284] In contrast adult women have a higher rate of asthma than men[22] and it is more common in the young than the old.[21] In 2010, children with asthma experienced over 900,000 emergency department visits, making it the most common reason for admission to the hospital following an emergency department visit in the US in 2011.[285][286]

Global rates of asthma have increased significantly between the 1960s and 2008[19][287] with it being recognized as a major public health problem since the 1970s.[21] Rates of asthma have plateaued in the developed world since the mid-1990s with recent increases primarily in the developing world.[288] Asthma affects approximately 7% of the population of the United States[203] and 5% of people in the United Kingdom.[289] Canada, Australia and New Zealand have rates of about 14–15%.[290]

The average death rate from 2011 to 2015 from asthma in the UK was about 50% higher than the average for the European Union and had increased by about 5% in that time.[291] Children are more likely see a physician due to asthma symptoms after school starts in September.[292]

Population-based epidemiological studies describe temporal associations between acute respiratory illnesses, asthma, and development of severe asthma with irreversible airflow limitation (known as the asthma-chronic obstructive pulmonary disease "overlap" syndrome, or ACOS).[293][294][295] Additional prospective population-based data indicate that ACOS seems to represent a form of severe asthma, characterised by more frequent hospitalisations, and to be the result of early-onset asthma that has progressed to fixed airflow obstruction.[296]

Economics

From 2000 to 2010, the average cost per asthma-related hospital stay in the United States for children remained relatively stable at about $3,600, whereas the average cost per asthma-related hospital stay for adults increased from $5,200 to $6,600.[297] In 2010, Medicaid was the most frequent primary payer among children and adults aged 18–44 years in the United States; private insurance was the second most frequent payer.[297] Among both children and adults in the lowest income communities in the United States there is a higher rate of hospital stays for asthma in 2010 than those in the highest income communities.[297]

History

Asthma was recognized in ancient Egypt and was treated by drinking an incense mixture known as kyphi.[20] It was officially named as a specific respiratory problem by Hippocrates circa 450 BC, with the Greek word for "panting" forming the basis of our modern name.[21] In 200 BC it was believed to be at least partly related to the emotions.[29] In the 12th century the Jewish physician-philosopher Maimonides wrote a treatise on asthma in Arabic, based partly on Arabic sources, in which he discussed the symptoms, proposed various dietary and other means of treatment, and emphasized the importance of climate and clean air.[298] Chinese Traditional Medicine also offered medication for asthma, as indicated by a surviving 14th century manuscript curated by the Wellcome Foundation.[299]

In 1873, one of the first papers in modern medicine on the subject tried to explain the pathophysiology of the disease while one in 1872, concluded that asthma can be cured by rubbing the chest with chloroform liniment.[300][301]

In 1886, F. H. Bosworth theorized a connection between asthma and

At the beginning of the 20th century, the focus was the avoidance of allergens as well as selective beta-2 adrenoceptors agonists were used as treatment strategies.[304][305]

Epinephrine was first referred to in the treatment of asthma in 1905.[306]

Oral corticosteroids began to be used for this condition in the 1950.

The use of a pressurized metered-dose inhaler in the mid-1950 has been developed for the administration of adrenaline and isoproterenol and was later used as a β2-adrenergic agonist.

Inhaled corticosteroids and selective short acting beta agonist came into wide use in the 1960s.[307][308]

A well-documented case in the 19th century was that of young Theodore Roosevelt (1858–1919). At that time there was no effective treatment. Roosevelt's youth was in large part shaped by his poor health partly related to his asthma. He experienced recurring nighttime asthma attacks that felt as if he was being smothered to death, terrifying the boy and his parents.[309]

During the 1930s to 1950s, asthma was known as one of the "holy seven"

In January 2021, an appeal court in France overturned a deportation order against a 40-year-old Bangladeshi man, who was a patient of asthma. His lawyers had argued that the dangerous levels of pollution in Bangladesh could possibly lead to worsening of his health condition, or even premature death.[311]

Notes

- ^ GINA 2011, p. 18

- ISBN 978-0-521-15255-6.

- ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-323-55087-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Asthma Fact sheet №307". WHO. November 2013. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- ^ PMID 20176271.

- ^ a b NHLBI Guideline 2007, pp. 169–72

- ^ a b c d e NHLBI Guideline 2007, p. 214

- ^ a b c d "Asthma–Level 3 cause" (PDF). The Lancet. 396: S108–S109. October 2020.

- ^ NHLBI Guideline 2007, pp. 11–12

- ^ GINA 2011, p. 20,51

- ^ (PDF) from the original on March 26, 2009.

- ^ OCLC 643462931.

- ISBN 978-0-7817-3390-8.

- ^ GINA 2011, p. 71

- ^ GINA 2011, p. 33

- ^ PMID 23822826.

- ^ a b c NHLBI Guideline 2007, pp. 373–75

- ^ S2CID 19525219.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8014-3720-5.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4160-4710-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i GINA 2011, pp. 2–5

- ISBN 978-93-5025-073-0. Archivedfrom the original on April 24, 2016.

- ISBN 978-0-7817-5273-2. Archivedfrom the original on May 5, 2016.

- ^ British Guideline 2009, p. 14

- ^ GINA 2011, pp. 8–9

- PMID 19336592.

- PMID 21702660.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-387-78285-0. Retrieved April 6, 2021.

- PMID 21674122.

- PMID 33446724.

- PMID 15249443.

- S2CID 2169875.

- S2CID 38550372.

- ISBN 978-3-642-36724-3.

- S2CID 49694304.

- ^ PMID 20604752.

- ^ PMID 17197483.

- PMID 18187692.

- PMID 17607004.

- PMID 21575714.

- S2CID 23213216.

- S2CID 37717160.

- ^ "Occupational Asthmagens - New York State Department of Health".

- ^ "Occupational Asthmagens - HSE".

- ^ GINA 2011, p. 6

- ^ GINA 2011, p. 61

- ^ S2CID 42988748.

- PMID 11427385.

- .

- PMID 20064771.

- PMID 18629304.

- PMID 20059582.

- PMID 26028642.

- PMID 26324808.

- PMID 36612391.

- PMID 23292157.

- PMID 23347656.

- S2CID 13520462.

- PMID 26541526.

- S2CID 35075329.

- S2CID 30418306.

- PMID 23101182.

- ^ PMID 18425868.

- PMID 25457152.

- PMID 25715323.

- ^ a b NHLBI Guideline 2007, p. 11

- S2CID 44556390.

- PMID 15878454.

- ^ S2CID 23664343.

- PMID 21710109.

- S2CID 26098640.

- ^ British Guideline 2009, p. 72

- PMID 21645799.

- S2CID 34049674.

- ^ PMID 17607003.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-84076-513-7. Archivedfrom the original on May 17, 2016.

- ^ S2CID 1887559.

- S2CID 36471997.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4160-2999-1.

- ^ GINA 2011, p. 4

- PMID 23045170.

- S2CID 34157182.

- PMID 19926826.

- PMID 19375453.

- PMID 17998992.

- PMID 12519582.

- PMID 24202435.

- PMID 15579370.

- PMID 29326337.

- ^ PMID 20568555.

- PMID 25159468.

- PMID 17493786.

- PMID 29518252.

- ^ a b NHLBI Guideline 2007, p. 42

- ^ GINA 2011, p. 20

- ^ American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology. "Five things physicians and patients should question" (PDF). Choosing Wisely. ABIM Foundation. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 3, 2012. Retrieved August 14, 2012.

- ^ Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (US). 2007. 07-4051 – via NCBI.

- PMID 20091514.

- ^ NHLBI Guideline 2007, p. 58

- PMID 17446617.

- ^ NHLBI Guideline 2007, p. 59

- ^ PMID 20516492.

- ISBN 978-1-264-26850-4.

- ^ OCLC 230848069.

- PMID 15301800.

- ^ Schiffman G (December 18, 2009). "Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease". MedicineNet. Archived from the original on August 28, 2010. Retrieved September 2, 2010.

- S2CID 38550372.

- ^ a b c d British Guideline 2009, p. 54

- ISBN 978-1-4613-1095-2. Archivedfrom the original on September 8, 2017.

- ISBN 978-0-07-146633-2.

- ISBN 978-1-4160-5350-7.

- from the original on April 29, 2015.

- PMID 11399724.

- ^ PMID 16473100.

- ^ PMID 22794687.

- ^ PMID 22370526.

- PMID 24379703.

- ^ GINA 2011, p. 17

- PMID 18394123.

- S2CID 20993439.

- S2CID 189906919.

- ^ PMID 22654084.

- ISBN 978-0-470-01184-3.

- ISBN 978-0-323-07081-2.

- PMID 22525387.

- ^ "Aspirin Exacerbated Respiratory Disease (AERD)". www.aaaai.org. American Academy of Allergy Asthma & Immunology. August 3, 2018. Archived from the original on September 18, 2018. Retrieved August 2, 2018.

- PMID 28124651.

- ^ PMID 24267355.

- PMID 25439352.

- PMID 2911321.

- PMID 33872336.

- PMID 36164333.

- ^ PMID 7636455.

- PMID 10719781.

- PMID 34163182.

- PMID 22205932.

- PMID 30206782.

- PMID 31917651.

- ^ a b NHLBI Guideline 2007, p. 46

- ISBN 978-0-323-22733-9. Archivedfrom the original on September 8, 2017.

- PMID 23282943.

- S2CID 12275555.

- PMID 16880365.

- ^ Diaz PK (2009). "23. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease". Applied therapeutics: the clinical use of drugs (9th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- ^ a b NHLBI Guideline 2007, pp. 184–85

- ^ "Asthma". World Health Organization. April 2017. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved May 30, 2017.

- S2CID 20728967.

- PMID 22235226.

- PMID 20053584.

- ^ S2CID 8172491.

- ^ S2CID 210985844.

- PMID 23450529.

- PMID 19630186.

- ^ S2CID 8532979.

- ISBN 978-1-4398-2759-8. Archivedfrom the original on May 6, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e NHLBI Guideline 2007, p. 213

- ^ a b "British Guideline on the Management of Asthma" (PDF). Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 19, 2008. Retrieved August 4, 2008.

- PMID 15241342.

- S2CID 13408225.

- PMID 16896426.

- PMID 15672843.

- PMID 17105779.

- PMID 17204725.

- S2CID 3183714.

- S2CID 36916271.

- ^ PMID 27649894.

- PMID 24842151.

- PMID 16856090.

- PMID 28828760.

- PMID 28402017.

- PMID 21975783.

- PMID 15846599.

- PMID 30687940.

- PMID 28972652.

- PMID 28394084.

- PMID 26410043.

- ^ NHLBI Guideline 2007, p. 69

- S2CID 25065026.

- PMID 21551404.

- PMID 23760885.

- PMID 24085631.

- PMID 27115477.

- PMID 22786526.

- PMID 16034941.

- ^ "QRG 153 • British guideline on the management of asthma" (PDF). SIGN. September 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2016. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- PMID 29938789.

- PMID 23634861.

- ^ PMID 23966133.

- ^ PMID 28076656.

- PMID 25080126.

- PMID 22513916.

- PMID 16490653.

- ^ NHLBI Guideline 2007, p. 351

- PMID 12804441.

- PMID 11279756.

- S2CID 11992578.

- ^ PMID 23235591.

- ^ NHLBI Guideline 2007, p. 218

- ^ PMID 20464739.

- ^ PMID 19821344.

- PMID 20393943.

- ^ PMID 19264689.

- PMID 22513944.

- PMID 18646149.

- ^ PMID 26594816.

- PMID 24459050.

- ^ PMID 28301050.

- PMID 22592708.

- PMID 26390230.

- ^ British Guideline 2009, p. 43

- PMID 24089325.

- ^ "Zyflo (Zileuton tablets)" (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. Cornerstone Therapeutics Inc. June 2012. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 13, 2014. Retrieved December 12, 2014.

- S2CID 41311909.

- PMID 12917970.

- PMID 15266477.

- PMID 14583965.

- PMID 10796540.

- S2CID 202567597.

- ^ GINA. "Difficult-to-Treat and Severe Asthma in Adolescent and Adult Patients: Diagnosis and Management". Global Initiative for Asthma. Retrieved August 1, 2021.

- PMID 22778497.

- PMID 31860697.

- PMID 34163182.

- PMID 25997166.

- ^ PMID 26089258.

- ^ NHLBI Guideline 2007, p. 250

- PMID 24037768.

- PMID 23235685.

- PMID 18425921.

- ^ S2CID 22386752.

- PMID 16412623.

- PMID 20604752.

- ISBN 978-1-4511-9215-5.

- PMID 27979015.

- ^ PMID 27580628.

- ^ PMID 27825189.

- PMID 24515516.

- S2CID 30182169.

- PMID 12171805.

- PMID 27126744.

- PMID 24865567.

- ^ PMID 29182799.

- ^ PMID 15006973.

- ^ GINA 2011, p. 37

- ^ NHLBI Guideline 2007, p. 399

- PMID 23152273.

- ^ PMID 20435668.

- PMID 22679610.

- ^ GINA 2011, p. 70

- FDA. July 25, 2018. Retrieved May 9, 2019.

- PMID 29939132.

- S2CID 44767865.

- S2CID 13681118.

- PMID 35838542.

- PMID 23532243.

- PMID 27687114.

- ^ PMID 35691614.

- PMID 11713120.

- S2CID 22129160.

- PMID 24154977.

- PMID 24936673.

- PMID 23794586.

- PMID 12137622.

- PMID 21412865.

- ^ PMID 36744416.

- ^ PMID 22696342.

- ^ a b NHLBI Guideline 2007, p. 240

- PMID 14973944.

- PMID 22972060.

- PMID 15846609.

- PMID 35993916.

- PMID 27070225.

- ISBN 978-0-7817-8943-1.

- ^ NHLBI Guideline 2007, p. 1

- ^ a b "The Global Asthma Report 2014". Archived from the original on April 27, 2016. Retrieved May 10, 2016.

- ISBN 978-92-4-156371-0.

- PMID 11818486.

- PMID 36335452.

- PMID 12554904.

- S2CID 8768325.

- ^ "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization. 2009. Archived from the original on November 11, 2009. Retrieved November 11, 2009.

- ^ "Asthma prevalence". Our World in Data. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- ^ World Health Organization. "WHO: Asthma". Archived from the original on December 15, 2007. Retrieved December 29, 2007.

- PMID 20008882.

- from the original on August 3, 2014.

- PMID 27931533.

- PMID 10452783.

- PMID 16175830.

- PMID 17189533.

- ^ Masoli M (2004). Global Burden of Asthma (PDF). p. 9. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 2, 2013.

- ^ "Asthma-related death rate in UK among highest in Europe, charity analysis finds". Pharmaceutical Journal. May 3, 2018. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved August 13, 2018.

- ^ "Asthma attacks triple when children return to school in September". NHS UK. July 3, 2019. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved August 23, 2019.

- PMID 22205932.

- PMID 26586037.

- PMID 15249443.

- S2CID 2169875.

- ^ from the original on March 28, 2014.

- ^ Rosner F (2002). "The Life of Moses Maimonides, a Prominent Medieval Physician" (PDF). Einstein Quart J Biol Med. 19 (3): 125–28. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 5, 2009.

- ^ C14 Chinese medication chart; Asthma etc. Wellcome L0039608

- PMID 20747287.

- PMID 20746575.

- PMID 20749546.

- PMID 21407325.

- PMID 29348936.

- PMID 36406816.

- PMID 18733372.

- S2CID 5143546.

- PMID 17092772.

- ISBN 978-0-7432-1830-6. Archivedfrom the original on April 7, 2015.

- ^ PMID 16185365.

- ^ "Bangladeshi man with asthma wins France deportation fight". The Guardian. January 12, 2021. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

References

- National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (2007). "Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma". National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. EPR-3.

- "British Guideline on the Management of Asthma" (PDF). British Thoracic Society. 2012 [2008]. SIGN 101. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 19, 2008. Retrieved August 4, 2008.

- British Guideline on the Management of Asthma. ISBN 978-1-909103-70-2. SIGN 158.

- "Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention" (PDF). Global Initiative for Asthma. 2011. Archived Reports.

External links

- WHO fact sheet on asthma

- Asthma at Curlie