Astraeus hygrometricus

| Astraeus hygrometricus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Division: | Basidiomycota |

| Class: | Agaricomycetes |

| Order: | Boletales |

| Family: | Diplocystaceae |

| Genus: | Astraeus |

| Species: | A. hygrometricus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Astraeus hygrometricus (

Morgan (1889) | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

|

Lycoperdon stellatus | |

| Astraeus hygrometricus mycorrhizal | |

|---|---|

| Edibility is inedible | |

Astraeus hygrometricus, commonly known as the hygroscopic earthstar, the barometer earthstar, or the false earthstar, is a species of

Despite a similar overall appearance, A. hygrometricus is not related to the true earthstars of genus

Taxonomy, naming, and phylogeny

Because this species resembles the earthstar fungi of Geastrum, it was placed in that genus by early authors, starting with

Astraeus hygrometricus has been given a number of

Studies in the 2000s showed that several species from Asian collection sites labelled under the specific epithet hygrometricus were actually considerably variable in a number of

A form of the species found in Korea and Japan, A. hygrometricus var. koreanus, was named by V.J. Stanĕk in 1958;

Description

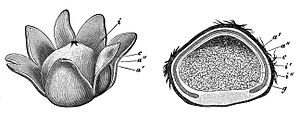

Young specimens of A. hygrometricus have roughly spherical

"This veritable barometer is the most theatrical of all the earthstars. A few minutes immersion in water will open up old, dried-up specimens that seem as tightly closed as clenched fists."

The fruit body is 1–8 cm (0.5–3 in) in diameter from tip to tip when expanded.

The spores are spherical or nearly so, reddish-brown, thick-walled and verrucose (covered with warts and spines). The spores' dimensions are 7–11

Edibility

North American sources list A. hygrometricus as inedible,[29] in some cases because of its toughness.[28][35][36] However, they are regularly consumed in Nepal[37] and South Bengal, where "local people consume them as delicious food".[38] They are collected from the wild and sold in the markets of India.[39][40]

A study of a closely related southeast Asian Astraeus species concluded that the fungus contained an abundance of

Similar species

Although A. hygrometricus bears a superficial resemblance to members of the "true earthstars" Geastrum, it may be readily differentiated from most by the hygroscopic nature of its rays. Hygroscopic earthstars include

Astraeus pteridis is larger, 5 to 15 cm (2 to 6 in) or more when expanded, and often has a more pronounced areolate pattern on the inner surface of the rays.[26] It is found in North America and the Canary Islands.[18] A. asiaticus and A. odoratus are two similar species known from throughout Asia and Southeast Asia, respectively.[18] A. odoratus is distinguished from A. hygrometricus by a smooth outer mycelial layer with few adhering soil particles, 3–9 broad rays, and a fresh odor similar to moist soil. The spore ornamentation of A. odoratus is also distinct from A. hygrometricus, with longer and narrower spines that often joined.[16] A. asiaticus has an outer peridial surface covered with small granules, and a gleba that is purplish-chestnut in color, compared to the smooth peridial surface and brownish gleba of A. hygrometricus. The upper limit of the spore size of A. asiaticus is larger than that of its more common relative, ranging from 8.75 to 15.2 μm.[18] A. koreanus (sometimes named as the variety A. hygrometricus var. koreanus; see Taxonomy) differs from the more common form in its smaller size, paler fruit body, and greater number of rays; microscopically, it has smaller spores (between 6.8 and 9 μm in diameter), and the spines on the spores differ in length and morphology.[16] It is known from Korea and Japan.[19]

Habitat, distribution, and ecology

Astraeus hygrometricus is an

The genus has a

Bioactive compounds

Mushroom

In addition to the previously known

Ethanol extracts of the fruit body are high in

Traditional beliefs

This earthstar has been used in

See also

- Medicinal mushrooms

References

- ^ a b "Astraeus hygrometricus (Pers.) Morgan 1889". MycoBank. International Mycological Association. Retrieved 2011-08-24.

- ^ PMID 24563840.

- ^ Persoon CH. (1801). Synopsis Methodica Fungorum (in Latin). Göttingen, Germany: Apud Henricum Dieterich. p. 135.

- ^ Morgan AP (1889). "North American fungi: the Gasteromycetes". Journal of the Cincinnati Society of Natural History. 12: 8–22.

- ^ ISBN 0-486-23033-3.

- ^ Lloyd CG (1902). The Geastrae. Bulletin of the Lloyd Library of Botany, Pharmacy and Materia Medica: Mycological Series, No. 2. Cincinnati, Ohio: J.U. & C.G. Lloyd. p. 8.

- OCLC 551312340.

- ^ Scopoli JA (1772). Flora Carniolica (in Latin). Vol. 2 (2nd ed.). Vienna, Austria: impensis Ioannis Pauli Krauss, bibliopolae vindobonensis. p. 489.

- ^ von Schweinitz LD (1822). "Synopsis fungorum Carolinae superioris". Schriften der Naturforschenden Gesellschaft in Leipzig (in Latin). 1: 59.

- ^ Engler A, Prantl K (1900). Die natürlichen Pflanzenfamilien nebst ihren Gattungen und wichtigeren Arten insbesondere den Nutzpflanzen: I. Tl., 1. Abt.: Fungi (Eumycetes) (in German). Vol. Teil 1, Abt.1**. Leipzig, Germany: W. Engelmann. p. 341.

- ^ ISBN 0-8131-9039-8.

- ^ ISBN 0-395-91090-0.

- ISBN 0-471-52229-5.

- ^ Rea C (1922). British Basidiomycetae: A Handbook to the Larger British Fungi. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 51.

- ^ "2005: Astraeus hygrometricus (Pers.) Morgan, Wetterstern" (in German). Deutsche Gesellschaft Für Mycologie (German Mycological Society). Retrieved 2011-08-25.

- ^ a b c d e f Phosri C, Watling R, Martín MP, Whalley AJ (2004). "The genus Astraeus in Thailand". Mycotaxon. 89 (2): 453–63.

- ^ .

- ^ PMID 17360168.

- ^ S2CID 85088635.

- ^ Stanĕk VJ (1958). "Rod Astraeus Morg.–Hvĕzdák". In Pilát A (ed.). Flora ČSR B-1: Gasteromycetes, Houby-Břichatky (Gasteromycetes-Puffballs) (in Czech). Prague: Nakladatelstvi Československé Akademie Ved. pp. 632, 819.

- .

- ^ ISBN 0-674-44555-4.

- ^ Gäumann EA, Dodge CW (1928). Comparative Morphology of Fungi. New York, New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company. p. 475.

- ISBN 0-316-70613-2.

- ^ Volk T. (2003). "Astraeus hygrometricus, an earth star. Tom Volk's Fungus of the Month for December 2003". University of Wisconsin-La Crosse, Department of Biology. Retrieved 2011-08-24.

- ^ ISBN 0-89815-169-4.

- ^ ISBN 0-520-03656-5.

- ^ ISBN 0-316-70613-2.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7627-3109-1.

- ISBN 0-7112-2378-5.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-58729-627-7.

- ^ ISBN 0-412-36970-2.

- ^ ISBN 0-947643-81-8.

- .

- ^ Wood M, Stevens F. "Astraeus hygrometricus". MykoWeb. California Fungi. Retrieved 2011-08-29.

- ISBN 0-472-85599-9.

- S2CID 6985365.

- ^ PMID 18206864.

- ^ PMID 21783909.

- ^ Harsh NS, Tiwari CK, Rai BK (1996). "Forest fungi in the aid of tribal women of Madhya Pradesh". Sustainable Forestry. 1 (1): 10–5.

- S2CID 44724095.

- ISBN 0-292-75125-7.

- ISBN 0-12-652840-3.

- ISBN 978-81-7141-980-7.

- ^ Balfour-Browne FL (1955). "Some Himalayan fungi". Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History). 1 (7): 187–218 (see p. 201).

- JSTOR 3760813.

- .

- PMID 17466905.

- PMID 20472019.

- PMID 20521989.

- ^ Pramanik A, Sirajul Islam S (1997). "Structural studies of a polysaccharide isolated from an edible mushroom, Astraeus hygrometricus". Trends in Carbohydrate Chemistry. 3: 57–64.

- ^ Pramanik A, Sirajul Islam S (2000). "Structural studies of a polysaccharide isolated from an edible mushroom, Astraeus hygrometricus". Indian Journal of Chemistry, Section B. 39B (7): 525–9.

- PMID 15337453.

- .

- S2CID 36705550.

- .

- ISBN 0-412-27060-9.

- ISSN 0412-1961.

- ^ Biswas G, Sarkar S, Acharya K (2010). "Free radical scavenging and anti-inflammatory activities of the extracts of Astraeus hygrometricus (Pers.) Morg". Latin American Journal of Pharmacy. 29 (4): 549–53.

- ^ Biswas G, Sarkar S, Acharya K (2011). "Hepatoprotective activity of the ethanolic extract of Astraeus hygrometricus (Pers.) Morg" (PDF). Digest Journal of Nanomaterials and Biostructures. 6 (2): 637–41. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-31.

- ISBN 1-884360-01-7.

- .

- ^ Burk W (1983). "Puffball usages among North American Indians" (PDF). Journal of Ethnobiology. 3 (1): 55–62.

External links