Aten

| Aten | |

|---|---|

Akhetaten, archaeological site known as Tell-el Amarna | |

| Symbol | Sun disk, reaching rays of light |

| Temples | Great Temple of the Aten, Small Aten Temple |

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Egyptian religion |

|---|

|

|

|

Aten also Aton, Atonu, or Itn (

Atenism and the worship of the Aten as the sole god of ancient Egypt state worship did not persist beyond Akhenaten's death. Not long after his death, one of Akhenaten's 18th dynasty successors, Tutankhamun, reopened the state temples to other Egyptian gods and re-positioned Amun as the preeminent solar deity. Aten is depicted as a solar disc emitting rays terminating in human hands.[2]

Etymology

The word Aten appears in the

Origins

The Aten was the disc of the sun and originally an aspect of Ra, the sun god in traditional ancient Egyptian religion. While the Aten was worshiped under the reign of Amenhotep III, it was made the sole deity to receive state and official cult worship under his successor Akhenaten, though archaeological evidence suggests the closing of the state temples of other Egyptian gods likely did not stop household worship of the traditional pantheon.[6] Inscriptions, such as the Great Hymn to the Aten, found in temples and tombs during Akhenaten's reign showcase the Aten as the creator, giver of life, and nurturing spirit of the world.[7] Aten does not have a creation myth or family but is mentioned in the Book of the Dead. The first known reference to Aten the sun-disk as a deity is in

Religion

Aten was extensively worshipped as a solar deity during the reign of Amenhotep III where it was depicted as a falcon-headed god like Ra. While Aten was the preeminent creator deity of a pantheon of ancient Egyptian gods under Amenhotep III, it was not until his successor that Aten would be the only god acknowledged via state worship.

In Atenism, night is a time to fear.[11] Work is done best when the sun, and thus Aten, is present. The Aten created all countries and people, and cares for every creature. According to the inscriptions, the Aten created a Nile river in the sky (rain) for the Syrians.[12] The rays of the sun disk only holds out life to the royal family, and because of this non-royals receives life from Akhenaten and Nefertiti, later Neferneferuaten, in exchange for loyalty to the Aten.[13] In inscriptions, like the Hymn to the Aten and the King, the Aten is depicted as caring for the people through Akhenaten, placing the royal family as intermediaries for the worship of the Aten.[14] There is only one known instance of the Aten talking.[15]

In the Hymn to Aten, a love for humanity and the Earth is depicted in Aten's mannerisms:

"Aten bends low, near the earth, to watch over his creation; he takes his place in the sky for the same purpose; he wearies himself in the service of the creatures; he shines for them all; he gives them sun and sends them rain. The unborn child and the baby chick are cared for; and Akhenaten asks his divine father to 'lift up' the creatures for his sake so that they might aspire to the condition of perfection of his father, Aten."[16]

Akhenaten represented himself as the son of Aten, mirroring many of his predecessors’ claims of divine birth and their positions as the embodiment of Horus. Akhenaten positioned himself as the only intermediary who could speak to Aten, emphasizing the dominance of Aten as the preeminent deity.[17] This has led to discussion of whether Atenism should be considered a monotheistic religion, and thus making it one of the first examples of monotheism.[3]

Aten is both a unique deity and a continuation of the traditional idea of a sun-god in ancient Egyptian religion, deriving a lot of the concepts of power and representation from the earlier solar deities like Ra, but building on top of the power Ra and many of his contemporaries represents. Aten carried absolute power in the universe, representing the life-giving force of light to the world as well as merging with the concept and goddess

Worship

The cult-center of the Aten was at the capital city Akhenaten founded, Akhetaten, In the worship of the Aten, the daily service of purification, anointment and clothing of the divine image that is traditionally found in ancient Egyptian worship was not performed. Instead, incense and food-stuff offerings such as meats, wines, and fruits were placed onto open-air altars.[22] A common scene in carved depictions of Akhenaten giving offering to Aten has him consecrating the sacrificed goods with a royal scepter.[23] Instead of barque-processions, the royal family rode in a chariot on festival days.[6] Elite women were known to worship the Aten in sun-shade temples in Akhetaten.[24]

Aten was considered to have been everywhere and intangible as Aten was the sunlight and energy in the world. Therefore, he did not have physical representations that other traditional ancient Egyptian gods had, instead represented via the sun disc and reaching rays of light tipped with human-like hands.[16] The explanation as to why the Aten could not be fully represented was that the Aten was beyond creation. Thus the inscriptions of scenes of gods carved in stone previously depicted animals and human forms instead showed the Aten as an orb above with life-giving rays stretching toward the royal figure. This power transcended human or animal form.[25]

Later, iconoclasm was enforced, and even sun disc depictions of Aten were prohibited in an edict issued by Akhenaten. In the edict, he stipulated that Aten's name was to be spelt phonetically.[26][27]

Two temples were central to the city of Akhetaten. The larger of the two had an "open, unroofed structure covering an area of about 800 by 300 metres (2,600 ft × 1,000 ft) at the northern end of the city".[28] Doorways had broken lintels and raised thresholds. Temples to the Aten were open-air structures with little-to-no roofing to maximize the amount of sunlight on the interior making them unique compared to other Egyptian temples of the time. Balustrades depict Akhenaten and the royal family embracing the rays of the Aten flanked stairwells, ramps, and altars. These fragments were initially identified as stele but were later reclassified as balustrades based on the presence of scenes on both sides.[29]

Inscriptions in tombs and temples during the Amarna Period often gave Aten a royal titulary enclosed in a double cartouche. Some have interpreted this to mean that Akhenaten was the embodiment of Aten, and the worship of Aten is directly worship of Akhenaten; but others have taken this as an indicator of Aten as the supreme ruler even over the current reigning royalty.[30][31]

There were two forms of the title; the first had the names of other gods, and the second later one was more 'singular' and referred only to the Aten himself. The early form was

Iconography

Architecture

Royal titulary

Question of monotheism

Ra-Horus, more usually referred to as Ra-Horakhty (Ra who is Horus of the two horizons), is a synthesis of two other gods, both of which are attested from very early on in ancient Egyptian religious practice. During the Amarna Period, this synthesis was seen as the invisible source of energy of the sun god, of which the visible manifestation was the Aten, the solar disk.

End of Atenism

As pharaoh, Akhenaten was considered the 'high priest' or even a prophet of the Aten, and during his reign was one of the main propagators of Atenism in Egypt. After the death of Akhenaten, Tutankhamun reinstated the cult of Amun, and the ban on the state worship of non-Atenism deities was lifted in favor of a return to the traditional ancient Egyptian pantheon.[2] The point of this transition can be seen in the name-change of Tutankhaten into Tutankhamun indicating the loss of favor in the worship of the Aten.[16] While there was no purge of the cult after Akhenaten's death, the Aten persisted in Egypt for another ten years or so until it seemed to fade. When Tutankhamun came into power, his religious reign was one of tolerance, with the major difference being that the Aten was no longer the only god worshiped within official, state capacity.[3] Tutankhamun made efforts to rebuild the state temples that were destroyed during Akhenaten's reign and reinstate the traditional pantheon of gods. This seemed to be "a move based publicly on the doctrine that Egypt's woes stemmed directly from its ignoring the gods, and in turn the gods' abandonment of Egypt".[3]

Names derived from Aten

- Akhenaten: "Effective spirit of the Aten".

- Akhetaten: "Horizon of the Aten", Akhenaten's capital. The archaeological site is known as Amarna.

- Ankhesenpaaten: "Her life is of the Aten".

- Beketaten: "Handmaid of the Aten".

- Meritaten: "She who is beloved of the Aten".

- Meketaten: "Behold the Aten" or "Protected by Aten".

- Neferneferuaten: "Beautiful are the beauties of Aten".

- Paatenemheb: "The Aten on jubilee".[clarification needed]

- Tutankhaten: "Living image of the Aten". Early name of Tutankhamun.

Gallery

-

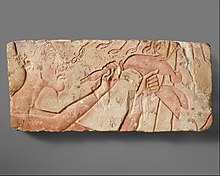

Relief fragment showing a royal head, probably Akhenaten, early form Aten cartouches, and Aten extending Ankh to the figure. Amarna, Egypt. New Kingdom, late 18th Dynasty. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London

-

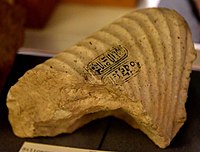

Limestone column fragment depicting reeds and an early form Aten cartouche. Reign of Akhenaten. Amarna, Egypt. New Kingdom, late 18th Dynasty. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London

-

Headless bust of Akhenaten or Nefertiti with four pairs of early form Aten cartouches, once part of a composite red quartzite statue with indications of Intentional damage. Amarna, Egypt. New Kingdom, late 18th Dynasty. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London

-

Inscribed limestone fragment showing early form Aten cartouches, "the Living Ra Horakhty". Amarna, Egypt. New Kingdom, late 18th Dynasty. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London

-

Fragment of a stele with three late form cartouches for Aten, one depicting a rare intermediate form of the god's name. Amarna, Egypt. New Kingdom, late 18th Dynasty. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London

-

Siliceous limestone fragment of a statue with late form Aten cartouches on the draped right shoulder. Amarna, Egypt. New Kingdom, late 18th Dynasty. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London

-

Wall relief with early form cartouches for Aten. Amarna, Egypt. New Kingdom, late 18th Dynasty. Neues Museum, Berlin, Germany.

-

Bronze plate with a cartouche of the throne name of Akhenaten (left) and two late form cartouches for Aten (middle, right). Amarna, Egypt. New Kingdom, late 18th Dynasty. Neues Museum, Berlin, Germany.

See also

- Ancient Egyptian Religion

- List of solar deities

- Amun

- Ra

- Akhenaten

- Nefertiti

- Ankhesenamun

- Meritaten

- The Egyptian

References

- ^ OCLC 522429289.

- ^ OCLC 48417401.

- ^ OCLC 10099207.

- )

- )

- ^ ISBN 9781607324690, retrieved March 3, 2023

- ^ OCLC 778434495.

- ^ OCLC 51668000.

- ^ Lichtheim, Miriam (1980). Ancient Egyptian Literature. Vol. 1. p. 223.

- OCLC 778435126.

- OCLC 48417401.

- OCLC 58393683.

- )

- OCLC 778435126.

- JSTOR 41431576– via JSTOR.

- ^ )

- ^ OCLC 778434495.

- ^ "Excavating Amarna - Archaeology Magazine Archive". archive.archaeology.org. Retrieved March 10, 2023.

- OCLC 778435126.

- ^ "Aten, God of Egypt". Retrieved February 24, 2023.

- ^ Alchin, Linda. "Aten". Retrieved February 24, 2023.

- ^ Steves, Anna. "Akhenaten, Nefertiti & Aten: From Many Gods to One". ARCE. Retrieved March 2, 2023.

- ISSN 0065-9991.

- S2CID 194880030.

- OCLC 15661054.

- ^ OCLC 64313016.

- OCLC 1328617320.

- )

- JSTOR 3821854.

- JSTOR 3855637.

- JSTOR 3854036.

- )

- OCLC 1312727419.

- OCLC 42923652.

External links

Media related to Aten at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Aten at Wikimedia Commons Works related to Great Hymn to Aten at Wikisource

Works related to Great Hymn to Aten at Wikisource