Atypical antipsychotic

| Atypical antipsychotic | |

|---|---|

| Drug class | |

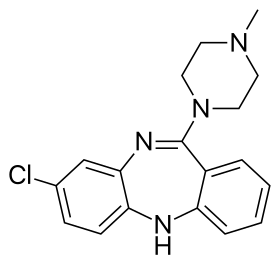

Skeletal formula of clozapine, the first atypical antipsychotic (1972) | |

| Synonyms | Second generation antipsychotic, serotonin–dopamine antagonist |

| Legal status | |

| In Wikidata | |

The atypical antipsychotics (AAP), also known as second generation antipsychotics (SGAs) and

Both generations of medication tend to block receptors in the brain's

As experience with these agents has grown, several studies have questioned the utility of broadly characterizing antipsychotic drugs as "atypical/second generation" as opposed to "first generation", noting that each agent has its own efficacy and side-effect profile. It has been argued that a more nuanced view in which the needs of individual patients are matched to the properties of individual drugs is more appropriate.

Medical uses

Atypical antipsychotics are typically used to treat

Schizophrenia

The first-line psychiatric treatment for schizophrenia is antipsychotic medication,

There is very little evidence on which to base a risk and benefit assessment of using antipsychotics for long-term treatment.[14]

The choice of which antipsychotic to use for a specific patient is based on benefits, risks, and costs.

Efficacy in the treatment of schizophrenia

The utility of broadly grouping the antipsychotics into first generation and atypical categories has been challenged. It has been argued that a more nuanced view, matching the properties of individual drugs to the needs of specific patients is preferable.

It has been suggested that there is no validity to the term "second-generation antipsychotic drugs" and that the drugs that currently occupy this category are not identical to each other in mechanism, efficacy, and side-effect profiles.[30]

Each drug has its own mechanism, as Dr. Rif S. El-Mallakh, explained regarding the binding site and occupancy with a focus on the dopamine D2 receptor:

In general, when an antagonist of a neurotransmitter receptor is used, it must occupy a minimum of 65% to 70% of the target receptor to be effective. This is clearly the case when the target is a postsynaptic receptor, such as the dopamine D2 receptor. Similarly, despite significant variability in antidepressant response, blockade of 65% to 80% of presynaptic transport proteins—such as the serotonin reuptake pumps when considering serotoninergic antidepressants, or the norepinephrine reuptake pumps when considering noradrenergic agents such as nortriptyline—is necessary for these medications to be effective.... Depending on the level of intrinsic activity of a partial agonist and clinical goal, the clinician may aim for a different level of receptor occupancy. For example, aripiprazole will act as a dopamine agonist at lower concentrations, but blocks the receptor at higher concentrations. Unlike antagonist antipsychotics, which require only 65% to 70% D2 receptor occupancy to be effective, aripiprazole receptor binding at effective antipsychotic doses is 90% to 95%. Since aripiprazole has an intrinsic activity of approximately 30% (i.e., when it binds, it stimulates the D2 receptor to about 30% of the effect of dopamine binding to the receptor), binding to 90% of the receptors, and displacing endogenous dopamine, allows aripiprazole to replace the background or tonic tone of dopamine, which has been measured at 19% in people with schizophrenia and 9% in controls. Clinically, this still appears as the minimal effective dose achieving maximal response without significant parkinsonism despite >90% receptor occupancy.[31]

Bipolar disorder

In bipolar disorder, SGAs are most commonly used to rapidly control

Major depressive disorder

In non-psychotic major depressive disorder (MDD), some SGAs have demonstrated significant efficacy as adjunctive agents; and, such agents include:[35][36][37][38]

whereas only quetiapine has demonstrated efficacy as a monotherapy in non-psychotic MDD.[40] Olanzapine/fluoxetine is an efficacious treatment in both psychotic and non-psychotic MDD.[41][42]

Autism

Both risperidone and aripiprazole have received FDA approval for irritability in autism.[41]

Dementia and Alzheimer's disease

Between May 2007 and April 2008, Dementia and Alzheimer's together accounted for 28% of atypical antipsychotic use in patients aged 65 or older.[46] The U.S. Food and Drug Administration requires that all atypical antipsychotics carry a black box warning that the medication has been associated with an increased risk of mortality in elderly patients.[46] In 2005, the FDA issued an advisory warning of an increased risk of death when atypical antipsychotics are used in dementia.[47] In the subsequent 5 years, the use of atypical antipsychotics to treat dementia decreased by nearly 50%.[47] As of now, the only FDA-approved atypical antipsychotic for alzheimer-related dementia is brexpiprazole.

Comparison table of efficacy

| Relative efficacy of SGAs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generic Drug Name[35][36][48][4][49] | Schizophrenia | Mania | Bipolar Maintenance | Bipolar Depression | Adjunct in Major Depressive Disorder |

| Amisulpride | +++ | ? | ? | ? | ? (+++ as a dysthymia monotherapy, however) |

| Aripiprazole | ++ | ++ | ++/+ | -[50] | +++ |

| Asenapine | +++ | ++ | ++ | ? (some evidence has suggested efficacy in treating depressive symptoms in mixed/manic episodes[51]) | ? |

| Blonanserin | ++ | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Cariprazine | +++ | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Clozapine | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ? |

| Iloperidone | + | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Lurasidone | + | ? | ? | +++[50] | ? |

| Melperone | +++/++ | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Olanzapine | +++ | +++ | ++ | +++/++ (+++ when combined with fluoxetine)[50] | ++ |

| Paliperidone | ++ | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Perospirone[52] | + | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Quetiapine | ++ | ++ | +++ | ++[50] | ++ |

| Risperidone | +++ | +++ | ++ | -[50] | + |

| Sertindole | ++ | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Ziprasidone | ++/+ | ++/+ | ? | -[50] | ? |

| Zotepine | ++ | ? | ? | ? | ? |

|

Legend:

| |||||

Adverse effects

The side effects reportedly associated with the various atypical antipsychotics vary and are medication-specific. Generally speaking, atypical antipsychotics are widely believed to have a lower likelihood for the development of tardive dyskinesia than the typical antipsychotics. However, tardive dyskinesia typically develops after long-term (possibly decades) use of antipsychotics. It is not clear if atypical antipsychotics, having been in use for a relatively short time, produce a lower incidence of tardive dyskinesia.[32][53]

Among the other side effects that have been suggested is that atypical antipsychotics increase the risk of cardiovascular disease.[54] Kabinoff and colleagues (2003) found that the increase in cardiovascular disease is seen regardless of the treatment received, and that it is instead caused by many different factors such as lifestyle or diet.[54]

Sexual side effects have also been reported when taking atypical antipsychotics.[55] In males antipsychotics reduce sexual interest, impair sexual performance with the main difficulties being failure to ejaculate.[56] In females there may be abnormal menstrual cycles and infertility.[56] In both males and females the breasts may become enlarged and a fluid will sometimes ooze from the nipples.[56] Sexual adverse effects caused by some antipsychotics are a result of an increase of prolactin. Sulpiride and Amisulpiride, as well as Risperdone and paliperidone (to a lesser extent), cause a high increase of prolactin.

In April 2005, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued an advisory and subsequent black box warning regarding the risks of atypical antipsychotic use among elderly patients with dementia. The FDA advisory was associated with decreases in the use of atypical antipsychotics, especially among elderly patients with dementia.[57] Subsequent research reports confirmed the mortality risks associated with the use of both conventional and atypical antipsychotics to treat patients with dementia. Consequently, in 2008 the FDA issued although a black box warning for classical neuroleptics. Data on treatment efficacies are strongest for atypical antipsychotics. Adverse effects in patients with dementia include an increased risk of mortality and cerebrovascular events, as well as metabolic effects, extrapyramidal symptoms, falls, cognitive worsening, cardiac arrhythmia, and pneumonia.[58] Conventional antipsychotics may pose an even greater safety risk. No clear efficacy evidence exists to support the use of alternative psychotropic classes (e.g. antidepressants, anticonvulsants).[59]

Drug-induced OCD

Many different types of medication can induce in patients that have never had symptoms before. A new chapter about OCD in the DSM-5 (2013) now specifically includes drug-induced OCD.

There are reports that some atypical antipsychotics could cause drug-induced OCD in already schizophrenic patients.[60][61][62][63]

Tardive dyskinesia

All of the atypical antipsychotics warn about the possibility of tardive dyskinesia in their package inserts and in the PDR. It is not possible to truly know the risks of tardive dyskinesia when taking atypicals, because tardive dyskinesia can take many decades to develop and the atypical antipsychotics are not old enough to have been tested over a long enough period of time to determine all of the long-term risks. One hypothesis as to why atypicals have a lower risk of tardive dyskinesia is because they are much less fat-soluble than the typical antipsychotics and because they are readily released from D2 receptor and brain tissue.[64] The typical antipsychotics remain attached to the D2 receptors and accumulate in the brain tissue which may lead to TD.[64]

Both typical and atypical antipsychotics can cause tardive dyskinesia.[65] According to one study, rates are lower with the atypicals at 3.9% per year as opposed to the typicals at 5.5% per year.[65]

Metabolism

Recently, metabolic concerns have been of grave concern to clinicians, patients and the FDA. In 2003, the

Recent evidence suggests a role of the α1 adrenoceptor and 5-HT2A receptor in the metabolic effects of atypical antipsychotics. The 5-HT2A receptor, however, is also believed to play a crucial role in the therapeutic advantages of atypical antipsychotics over their predecessors, the typical antipsychotics.[68]

The two atypical antipsychotics with trials showing that had a low incidence of weight gain in large meta-analysis were lurasidone and aripiprazole.[69] In a meta-analysis of 18 antipsychotics, olanzapine and clozapine exhibited the worst metabolic parameters and aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, cariprazine, lurasidone, and ziprasidone the most benign parameters.[70] Aripiprazole, asenapine, ziprazidone and lurasidone have low propensity to cause weight gain.[71] Lumateperone was found to cause minimal weight gain in a long-term 12 month follow-up study.[72]

A study by Sernyak and colleagues found that the prevalence of diabetes in atypical antipsychotic treatments was statistically significantly higher than that of conventional treatment.[54] The authors of this study suggest that it is a causal relationship the Kabinoff et al. suggest the findings only suggest a temporal association.[54] Kabinoff et al. suggest that there is insufficient data from large studies to demonstrate a consistent or significant difference in the risk of insulin resistance during treatment with various atypical antipsychotics.[54] Prescribing topiramate, zonisamide, metformin, GLP-1 receptor agonists, or nizatidine alongside an antipsychotic significantly reduces weight gain.[73]

Despite increasing some risk factors, SGAs are not associated with excess cardiovascular mortality when used to treat serious psychiatric disorders.[74]

Comparison table of adverse effects

| Comparison of side effects for atypical antipsychotics | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generic Name | Weight gain | Metabolic Effects | EPS | High prolactin |

Sedation | Hypotension / Orthostasis | QTc prolongation | Anti-ACh effects | Other adverse effects | |||||

| Amisulpride | + | + | + | ++ | - | - | +++ | - | Seizures, suicidal ideation

| |||||

| Aripiprazole | 0–10%[75] | 0–10%[75] | 10–20%[75] | -[75] | 10–20%[75] | 0–10%[75] | - | - | Seizures (0.1–0.3%), anxiety, rhabdomyolysis, pancreatitis (<0.1%), agranulocytosis (<1%), leukopenia, neutropenia, suicidal ideation, angioedema (0.1–1%) | |||||

| Asenapine | 0–10%[75] | 20%[75] | 0–10%[75] | 0–10%[75] | 10–20%[75] | 0–10%[75] | + | - | Immune hypersensitivity reaction , angioedema, suicidal ideation

| |||||

| Blonanserin | +/- | - | ++ | + | +/- | - | + | +/- | ||||||

| Clozapine | 20–30%[75] | 0–15%[75] | -[75] | -[75] | >30%[75] | 20–30%[75] | + | +++ | Seizures (3–5%), agranulocytosis (1.3%), leukopenia, angle-closure glaucoma, eosinophilia (1%), thrombocytopenia, Stevens–Johnson syndrome, myocarditis, erythema multiforme and abnormal peristalsis

| |||||

| Iloperidone | 0–10%[75] | 0–10%[75] | 0–10%[75] | -[75] | 10–20%[75] | 0–10%[75] | ++ | - | Suicidal ideation (0.4–1.1%), syncope (0.4%) | |||||

| Lurasidone | -[75] | -[75] | >30%[75] | -[75] | 20–30%[75] | -[75] | + | + | Agranulocytosis, seizures (<1%), elevated serum creatinine (2–4%) | |||||

| Melperone | + | + | +/- | - | +/++ | +/++ | ++ | - | Agranulocytosis, neutropenia and leukopenia | |||||

| Olanzapine | 20–30%[75] | 0–15%[75] | 20-30%[75] | 20–30%[75] | >30%[75] | 0–10%[75] | + | + | Acute haemorrhagic pancreatitis, immune hypersensitivity reaction, seizures (0.9%), status epilepticus, suicidal ideation (0.1–1%) | |||||

| Paliperidone | 0–10%[75] | -[75] | 10–20%[75] | >30%[75] | 20–30%[75] | 0–10%[75] | +/- (7%) | - | Agranulocytosis, leukopenia, priapism, dysphagia, hyperprolactinaemia, sexual dysfunction[76] | |||||

| Perospirone | ? | ? | >30%[77] | + | + | + | ? | - | Insomnia in up to 23%, | |||||

| Quetiapine | 20–30%[75] | 0–15%[75] | 10–20%[75] | -[75] | >30%[75] | 0–10%[75] | ++ | + | Agranulocytosis, leukopenia, neutropenia (0.3%), anaphylaxis, seizures (0.05–0.5%), priapism, tardive dyskinesia (0.1–5%), suicidal ideation, pancreatitis, syncope (0.3–1%) | |||||

| Remoxipride[78] | +/- | - | - | -[64] | - | +/- | ? | - | There is a risk of aplastic anaemia risk which is what led to its removal from the market.

| |||||

| Risperidone | 10–20%[75] | 0–10%[75] | 20–30%[75] | >30%[75] | >30%[75] | 0–10%[75] | + | - | Syncope (1%), pancreatitis, hypothermia, agranulocytosis, leukopenia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, cerebrovascular incident (<5%), tardive dyskinesia (<5%), priapism, neuroleptic malignant syndrome (<1%), gynecomastia, galactorrhea[79]

| |||||

| Sertindole | ++ | +/- | - | ++ | - | +++ | +++ | - | - | |||||

| Sulpiride | + | + | + | +++ | - | +++ | + | - | Jaundice | |||||

| Ziprasidone | 0–10%[75] | 0–10%[75] | 0–10%[75] | -[75] | 20–30%[75] | 0–10%[75] | ++ | - | Syncope (0.6%), dysphagia (0.1–2%), bone marrow suppression, seizure (0.4%), priapism | |||||

Discontinuation

The British National Formulary recommends a gradual withdrawal when discontinuing antipsychotics to avoid acute withdrawal syndrome or rapid relapse.[80] Symptoms of withdrawal commonly include nausea, vomiting, and loss of appetite.[81] Other symptoms may include restlessness, increased sweating, and trouble sleeping.[81] Less commonly there may be a feeling of the world spinning, numbness, or muscle pains.[81] Symptoms generally resolve after a short period of time.[81]

There is tentative evidence that discontinuation of antipsychotics can result in psychosis.[82] It may also result in reoccurrence of the condition that is being treated.[83] Rarely tardive dyskinesia can occur when the medication is stopped.[81]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

The atypical antipsychotics integrate with the serotonin (5-HT), norepinephrine (α, β), and dopamine (DA) receptors in order to effectively treat schizophrenia.[84]

Brexpiprazole, approved by the US FDA in 2015, has a similar binding profile to aripiprazole as a partial D2 agonist with moderate histamine binding, but with brexipiprazole has a higher affinity for serotonin receptor 5-HT2A

Some effects of

Whether the anhedonic, loss of pleasure and motivation effect resulting from dopamine insufficiency or blockade at D2 receptors in the mesolimbic pathway, which is mediated in some part by antipsychotics (and despite dopamine release in the mesocortical pathway from 5-HT2A antagonism, which is seen in atypical antipsychotics), or the positive mood, mood stabilization, and cognitive improvement effect resulting from atypical antipsychotic serotonergic activity is greater for the overall quality of life effect of an atypical antipsychotic is a question that is variable between individual experience and the atypical antipsychotic(s) being used.[85]

Terms

Inhibition. Disinhibition: The opposite process of inhibition, the turning on of a biological function. Release: Causes the appropriate neurotransmitters to be discharged in vesicles into the synapse where they attempt to bind to and activate a receptor. Downregulation and Upregulation.[citation needed]

Binding profile

Note: Unless otherwise specified, the drugs below serve as antagonists/inverse agonists at the receptors listed.

| Generic Name[112] | D1 | D2 | D3 | D4 | 5-HT1A | 5-HT1B | 5-HT2A | 5-HT2C | 5-HT6 | 5-HT7 | α1A | α1 | α2 | M1 | M3 | H1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amisulpride | - | ++++ | ++++ | - | - | - | - | - | - | ++/+ | - | +/- | - | - | - | |

| Aripiprazole | + | ++++ (PA) | +++ (PA) | + (PA) | +++ (PA) | + | +++ | ++ (PA) | + | +++ (PA) | ++/+ | + | - | - | ++/+ | |

| Asenapine | +++ | +++ | ++++ | +++ | +++ (PA) | +++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | +++ | +++ | - | - | +++ | |

| Blonanserin | - | ++++ | ++++ | + | - | ? | +++ | + | + | +/- | + (RC) | + (RC) | + | ? | - | |

| Brexpiprazole | ++ | +++++ (PA) | ++++ (PA) | ++++ | +++++ (PA) | +++ | +++++ | +++ (PA) | +++ | ++++ | ++ | - | +++ | |||

| Cariprazine | ++++ (PA) | +++++ (PA) | ++++ (PA) | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | - | - | +++ | ||||||

| Clozapine | ++ | ++ | ++ | +++ | ++ (PA) | ++/+ | ++++ | ++++ | +++ | +++ | ++++ | +++ | ++++ | +++ | ++++ | |

| Iloperidone | + | +++ | +++ | ++ | + (PA) | + | +++ | + | ++ | + | ++++ | +++/++ | - | - | +++ | |

| Lurasidone | + | ++++ | ++ | ++ | +++ (PA) | ? | ++++ | +/- | ? | ++++ | - | +++/++ | - | - | - | |

| Melperone | ? | ++ | ++++ | ++ | + (PA) | ? | ++ | + | - | ++ | ++ | ++ | - | - | ++ | |

| Olanzapine | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | + (PA) | ++ | ++++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | |

| Paliperidone | ++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | + (PA) | +++/++ | ++++ | + | - | ++++/+++ | +++ | +++ | - | - | +++/++ | |

| Quetiapine | + | ++/+ | ++/+ | + | ++/+ (PA) | + | + | + | ++ | +++/++ | ++++ | +++/++ | ++ | +++ | ++++ | |

| Risperidone | ++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | + (PA) | ++ | ++++ | ++ | - | +++/++ | ++ | +++/++ | ++ | - | - | ++ |

| Sertindole | ? | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++/+ (PA) | ++ | ++++ | ++++ | +++ | ++ | ++++/+++ | + | - | - | ++/+ | |

| Sulpiride | ? | ++++ | ++++ | +++ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Ziprasidone | +++/++ | +++ | +++ | +++/++ | +++ (PA) | +++ (PA) | ++++ | +++(PA) | ++ | +++ | +++/++ | ++ | - | - | ++ | |

| Zotepine | +++/++ | +++ | ++++/+++ | +++ | ++ (PA) | +++ | ++++ | ++++ (RC) | ++++ | ++++/+++ | +++ | +++/++ | ++ (RC) | ++ (RC) | ++++ |

Legend:

| No Affinity or No Data | |

| - | Clinically Insignificant |

| + | Low |

| ++ | Moderate |

| +++ | High |

| ++++ | Very High |

| +++++ | Exceptionally High |

| PA | Partial Agonist |

| RC | Cloned Rat Receptor |

Pharmacokinetics

Atypical antipsychotics are most commonly administered orally.[56] Antipsychotics can also be injected, but this method is not as common.[56] They are lipid-soluble, are readily absorbed from the digestive tract, and can easily pass the blood–brain barrier and placental barriers.[56] Once in the brain, the antipsychotics work at the synapse by binding to the receptor.[113] Antipsychotics are completely metabolized in the body and the metabolites are excreted in urine.[56] These drugs have relatively long half-lives.[56] Each drug has a different half-life, but the occupancy of the D2 receptor falls off within 24 hours with atypical antipsychotics, while lasting over 24 hours for the typical antipsychotics.[64] This may explain why relapse into psychosis happens quicker with atypical antipsychotics than with typical antipsychotics, as the drug is excreted faster and is no longer working in the brain.[64] Physical dependence with these drugs is very rare.[56] However, if the drug is abruptly discontinued, psychotic symptoms, movement disorders, and sleep difficulty may be observed.[56] It is possible that withdrawal is rarely seen because the AAP are stored in body fat tissues and slowly released.[56]

| Pharmacokinetic parameters of available atypical antipsychotics[114][115][116] | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug | Route(s) of Administration[Note 1] | Half-life (t1/2 in hours) | Volume of distribution (Vd in L/kg) | Protein binding | Excretion | Enzymes involved in metabolism | Bioavailability | Peak plasma time (h) | Cmax (ng/mL) |

| Amisulpride | Oral | 12 | 5.8 | 16% | Urine (50%), faeces (20%; 70% of this is as unchanged drug)[Note 2] | ? | 48% | Two peaks: 1 hr & 3-4 hrs post-oral dosing | 39±3 (1 hr), 54±4 (3-4 hrs) |

| Aripiprazole | Oral, intramuscular (including depot) | 75 (94 for active metabolite) | 4.9 | 99% | Faeces (55%), urine (25%) | CYP2D6 & CYP3A4 | 87% (Oral), 100% ( IM ) |

3-5 | ? |

| Asenapine | Sublingual | 24 | 20-25 | 95% | Urine (50%), faeces (40%) | CYP1A2 & UGT1A4 | 35% (sublingual), <2% (Oral) | 0.5-1.5 | 4 |

| Blonanserin[117] | Oral | 10.7 (single 4 mg dose), 12 (single 8 mg dose), 16.2 (single 12 mg dose), 67.9 (repeated bid dosing) | ? | >99.7% | Urine (59%), faeces (30%) | CYP3A4 | 84% (Oral) | <2 | 0.14 (single 4 mg dose), 0.45 (single 8 mg dose), 0.76 (single 12 mg dose), 0.57 (bid dosing) |

| Clozapine | Oral | 8 hours (single dosing), 12 (twice daily dosing) | 4.67 | 97% | Urine (50%), faeces (30%) | CYP1A2, CYP3A4, CYP2D6 | 50-60% | 1.5-2.5 | 102-771 |

| Iloperidone | Oral | ? | 1340-2800 | 95% | Urine (45-58%), faeces (20-22%) | CYP2D6 & CYP3A4 | 96% | 2-4 | ? |

| Lurasidone | Oral | 18 | 6173 | 99% | Faeces (80%), urine (9%) | CYP3A4 | 9-19% | 1-3 | ? |

| Melperone[118][119] | Oral, intramuscular | 3–4 (oral), 6 (IM) | 7–9.9 | 50% | Urine (70% as metabolites; 5–10.4% unchanged drug) | ? | 65% (tablet), 87% (IM), 54% (oral syrup) | 0.5–3 | 75–324 (repeated dosing) |

| Olanzapine | Oral, intramuscular (including depot) | 30 | 1000 | 93% | Urine (57%), faeces (30%) | CYP1A2, CYP2D6 | >60% | 6 (Oral) | ? |

| Paliperidone | Oral, intramuscular (including depot) | 23 (Oral) | 390-487 | 74% | Urine (80%), faeces (11%) | CYP2D6, CYP3A4 | 28% | 24 (Oral) | ? |

| Perospirone[77] | Oral | ? | ? | 92% | Urine (0.4% as unchanged drug) | ? | ? | 1.5 | 1.9-5.7 |

| Quetiapine | Oral | 6 (IR), 7 (XR) | 6-14 | 83% | Urine (73%), faeces (20%) | CYP3A4 | 100% | 1.5 (IR), 6 (XR) | ? |

| Risperidone | Oral, intramuscular (including depot) | 3 (EM) (oral), 20 (PM) (oral) | 1-2 | 90%, 77% (metabolite) | Urine (70%), faeces (14%) | CYP2D6 | 70% | 3 (EM), 17 (PM) | ? |

| Sertindole | Oral | 72 (55-90) | 20 | 99.5% | Urine (4%), faeces (46-56%) | CYP2D6 | 74% | 10 | ? |

| Ziprasidone | Oral, intramuscular | 7 (oral) | 1.5 | 99% | Faeces (66%), urine (20%) | CYP3A4 & CYP1A2 | 60% (Oral), 100% (IM) | 6-8 | ? |

| Zotepine[120][121] | Oral | 13.7-15.9 | 10-109 | 97% | Urine (17%) | ? | 7-13% | ? | ? |

|

Acronyms used: | |||||||||

| Medication | Brand name | Class | Vehicle | Dosage | Tmax | t1/2 single | t1/2 multiple | logPc | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aripiprazole lauroxil | Aristada | Atypical | Watera | 441–1064 mg/4–8 weeks | 24–35 days | ? | 54–57 days | 7.9–10.0 | |

Aripiprazole monohydrate |

Abilify Maintena | Atypical | Watera | 300–400 mg/4 weeks | 7 days | ? | 30–47 days | 4.9–5.2 | |

| Bromperidol decanoate | Impromen Decanoas | Typical | Sesame oil | 40–300 mg/4 weeks | 3–9 days | ? | 21–25 days | 7.9 | [122] |

Clopentixol decanoate |

Sordinol Depot | Typical | Viscoleob | 50–600 mg/1–4 weeks | 4–7 days | ? | 19 days | 9.0 | [123] |

Flupentixol decanoate |

Depixol | Typical | Viscoleob | 10–200 mg/2–4 weeks | 4–10 days | 8 days | 17 days | 7.2–9.2 | [123][124] |

Fluphenazine decanoate |

Prolixin Decanoate | Typical | Sesame oil | 12.5–100 mg/2–5 weeks | 1–2 days | 1–10 days | 14–100 days | 7.2–9.0 | [125][126][127] |

Fluphenazine enanthate |

Prolixin Enanthate | Typical | Sesame oil | 12.5–100 mg/1–4 weeks | 2–3 days | 4 days | ? | 6.4–7.4 | [126] |

| Fluspirilene | Imap, Redeptin | Typical | Watera | 2–12 mg/1 week | 1–8 days | 7 days | ? | 5.2–5.8 | [128] |

| Haloperidol decanoate | Haldol Decanoate | Typical | Sesame oil | 20–400 mg/2–4 weeks | 3–9 days | 18–21 days | 7.2–7.9 | [129][130] | |

Olanzapine pamoate |

Zyprexa Relprevv | Atypical | Watera | 150–405 mg/2–4 weeks | 7 days | ? | 30 days | – | |

| Oxyprothepin decanoate | Meclopin | Typical | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | 8.5–8.7 | |

Paliperidone palmitate |

Invega Sustenna | Atypical | Watera | 39–819 mg/4–12 weeks | 13–33 days | 25–139 days | ? | 8.1–10.1 | |

Perphenazine decanoate |

Trilafon Dekanoat | Typical | Sesame oil | 50–200 mg/2–4 weeks | ? | ? | 27 days | 8.9 | |

| Perphenazine enanthate | Trilafon Enanthate | Typical | Sesame oil | 25–200 mg/2 weeks | 2–3 days | ? | 4–7 days | 6.4–7.2 | [131] |

Pipotiazine palmitate |

Piportil Longum | Typical | Viscoleob | 25–400 mg/4 weeks | 9–10 days | ? | 14–21 days | 8.5–11.6 | [124] |

Pipotiazine undecylenate |

Piportil Medium | Typical | Sesame oil | 100–200 mg/2 weeks | ? | ? | ? | 8.4 | |

| Risperidone | Risperdal Consta | Atypical | Microspheres |

12.5–75 mg/2 weeks | 21 days | ? | 3–6 days | – | |

Zuclopentixol acetate |

Clopixol Acuphase | Typical | Viscoleob | 50–200 mg/1–3 days | 1–2 days | 1–2 days | 4.7–4.9 | ||

Zuclopentixol decanoate |

Clopixol Depot | Typical | Viscoleob | 50–800 mg/2–4 weeks | 4–9 days | ? | 11–21 days | 7.5–9.0 | |

| Note: All by . Sources: Main: See template. | |||||||||

History

The first major tranquilizer or antipsychotic medication, chlorpromazine (Thorazine), a typical antipsychotic, was discovered in 1951 and introduced into clinical practice shortly thereafter. Clozapine (Clozaril), an atypical antipsychotic, fell out of favor due to concerns over drug-induced agranulocytosis. Following research indicating its effectiveness in treatment-resistant schizophrenia and the development of an adverse event monitoring system, clozapine re-emerged as a viable antipsychotic. According to Barker (2003), the three most-accepted atypical drugs are clozapine, risperidone, and olanzapine. However, he goes on to explain that clozapine is usually the last resort when other drugs fail. Clozapine can cause agranulocytosis (a decreased number of white blood cells), requiring blood monitoring for the patient. Despite the effectiveness of clozapine for treatment-resistant schizophrenia, agents with a more favorable side-effect profile were sought for widespread use. During the 1990s, olanzapine, risperidone, and quetiapine were introduced, with ziprasidone and aripiprazole following in the early 2000s. The atypical antipsychotic paliperidone was approved by the FDA in late 2006.[citation needed]

The atypical antipsychotics have found favor among clinicians and are now considered to be

The terminology can still be imprecise. The definition of "atypicality" was based upon the absence of extrapyramidal side effects, but there is now a clear understanding that atypical antipsychotics can still induce these effects (though to a lesser degree than typical antipsychotics).[133] Recent literature focuses more upon specific pharmacological actions and less upon categorization of an agent as "typical" or "atypical". There is no clear dividing line between the typical and atypical antipsychotics therefore categorization based on the action is difficult.[64]

More recent research is questioning the notion that second-generation antipsychotics are superior to first generation typical antipsychotics. Using a number of parameters to assess quality of life, Manchester University researchers found that typical antipsychotics were no worse than atypical antipsychotics. The research was funded by the National Health Service (NHS) of the UK.[134] Because each medication (whether first or second generation) has its own profile of desirable and adverse effects, a neuropsychopharmacologist may recommend one of the older ("typical" or first generation) or newer ("atypical" or second generation) antipsychotics alone or in combination with other medications, based on the symptom profile, response pattern, and adverse effects history of the individual patient.

Society and culture

Between May 2007 and April 2008, 5.5 million Americans filled at least one prescription for an atypical antipsychotic.[46] In patients under the age of 65, 71% of patients were prescribed an atypical antipsychotic to treat Schizophrenia or Bipolar Disorder where this dropped to 38% in patients aged 65 or above.[46]

Despite the name "antipsychotics", the drugs are commonly used for a variety of conditions that do not involve psychosis. Some healthcare professionals reported avoiding the name "atypical antipsychotic" when prescribing the drug to patients who had bipolar disorder.[135]

Regulatory status

| Regulatory status of second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) as of July 2013[update] | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generic name | United States FDA approved |

Canada HPFB approved[136] |

Australia TGA approved[137] |

Europe EMA approved[138] |

Japan PMDA approved[139] |

United Kingdom MHRA approved[140][141][138] | ||||||||

| Amisulpride | No | No | Yes | (some members) | No | Yes | ||||||||

| Aripiprazole | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||||

| Asenapine | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||||

| Blonanserin | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | ||||||||

| Carpipramine | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | ||||||||

| Clocapramine | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | ||||||||

| Clozapine | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||||

| Iloperidone | Yes | No | No | Refused | No | No | ||||||||

| Lurasidone | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | ||||||||

| Melperone | No | No | No | No | No | No | ||||||||

| Mosapramine | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | ||||||||

| Olanzapine | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||||

| Paliperidone | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||||

| Perospirone | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | ||||||||

| Pimavanserin | Yes | No | No | Investigational | No | (No) | ||||||||

| Quetiapine | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||||

| Remoxipride | No | No | No | Withdrawn | No | No | ||||||||

| Risperidone | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||||

| Sertindole | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | ||||||||

| Sulpiride | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||||

| Ziprasidone | Yes | Yes | Yes | (some members) | No | Yes | ||||||||

| Zotepine | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | ||||||||

Notes

- ^ The route of administration in this category refers to the standard means of administration when the drug is being used in its capacity as an atypical antipsychotic, not for other purposes. For example, amisulpride can be administered intravenously as an antiemetic drug but this is not its standard route of administration when being used as an antipsychotic

- ^ Note these values are from a study in of which amisulpride was intravenously administered

Stahl: AP Explained 1

See also

References

- PMID 23006237.

- OCLC 881019573.

- ^ S2CID 1071537.

- ^ S2CID 32085212.

- PMID 18185824.

- S2CID 19951248.

- ^ "Respiridone". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved April 3, 2011.

- PMID 21954480.

- ISBN 978-0-19-920631-5.

- PMID 22376048.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link - ^ "Schizophrenia: Full national clinical guideline on core interventions in primary and secondary care" (PDF). Gaskell and the British Psychological Society. National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. March 25, 2009. Retrieved November 25, 2009.

- S2CID 4907333.

- PMID 25528757.

- PMID 27802977.

- S2CID 208792724.

- PMID 20954430.

- PMID 17619525.

- PMID 20704164.

- PMID 27388573.

- PMID 26338693.

- PMID 31974576.

- PMID 21254289.

- PMID 11099280.

- PMID 16172203.

- PMID 16585435.

- S2CID 34935.

- PMID 22936056.

- .

- S2CID 2669203.

- ISBN 978-0307452412.

- ^ "Receptor occupancy and drug response: Understanding the relationship". www.mdedge.com. Retrieved October 14, 2022.

- ^ a b c Taylor D, Paton C, Kapur S (2012). The Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines (12th ed.). Informa Healthcare. pp. 12–152, 173–196, 222–235.

- ^ Soreff S, McInnes LA, Ahmed I, Talavera F (August 5, 2013). "Bipolar Affective Disorder Treatment & Management". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved October 10, 2013.

- ^ Post RM, Keck P (July 30, 2013). "Bipolar Disorder in adults: Maintenance treatment". UpToDate. Wolters Kluwer Health. Retrieved October 10, 2013.

- ^ PMID 21154393.

- ^ PMID 23554581.

- PMID 19687129.

- ^ Research Cf. "Drug Approvals and Databases - Drug Trials Snapshots: REXULTI for the treatment of major depressive disorder". www.fda.gov. Retrieved October 18, 2018.

- PMID 26085041.

- PMID 23017200.

- ^ a b Truven Health Analytics, Inc. DRUGDEX System (Internet) [cited 2013 Oct 10]. Greenwood Village, CO: Thomsen Healthcare; 2013.

- S2CID 36295165.

- ^ S2CID 24264818.

- ^ "U.S. FDA Approves Otsuka and Lundbeck's REXULTI (Brexpiprazole) as Adjunctive Treatment for Adults with Major Depressive Disorder and as a Treatment for Adults with Schizophrenia | Discover Otsuka". Otsuka in the U.S. Retrieved October 18, 2018.

- ^ "DailyMed - CAPLYTA- lumateperone capsule". dailymed.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved January 11, 2023.

- ^ PMID 19727265.

- ^ PMID 21191528.

- S2CID 25512763.

- PMID 19851515.

- ^ S2CID 23324764.

- PMID 21689438.

- S2CID 11543666.

- ^ Stroup TS, Marder S, Stein MB (October 23, 2013). "Pharmacotherapy for schizophrenia: Acute and maintenance phase treatment". UpToDate. Wolters Kluwer. Retrieved October 10, 2013.

- ^ PMID 15156241.

- PMID 18458771.

- ^ OCLC 1301978997.

- PMID 20065205.

- PMID 23929443.

- PMID 22952071.

- PMID 15231024.

- PMID 23112432.

- S2CID 276209.

- PMID 22942882.

- ^ PMID 11873706.

- ^ S2CID 37288246.

- ^ PMID 14747245.

- ^ Brunton L, Chabner B, Knollman B (2010). Goodman and Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (12th ed.). McGraw Hill Professional. pp. 417–455.

- S2CID 43719333.

- S2CID 13769615.

- S2CID 209434994.

- ^ Dayabandara M, Hanwella R, Ratnatunga S, Seneviratne S, Suraweera C, de Silva VA. Antipsychotic-associated weight gain: management strategies and impact on treatment adherence. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2017 Aug 22;13:2231-2241. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S113099. PMID: 28883731; PMCID: PMC5574691.

- ^ Satlin A, Durgam S, Vanover KE, Davis RE, Huo J, Mates S, Correll C. M205. LONG-TERM SAFETY OF LUMATEPERONE (ITI-007): METABOLIC EFFECTS IN A 1-YEAR STUDY. Schizophr Bull. 2020 May;46(Suppl 1):S214. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbaa030.517. Epub 2020 May 18. PMCID: PMC7234755.

- S2CID 236451973.

- PMID 32356562.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh "Comparison of Common Side Effects of Second Generation Atypical Antipsychotics". Facts & Comparisons. Wolters Kluwer Health. Retrieved March 31, 2012.

- ^ PMID 23596605.

- ^ S2CID 262520276.

- S2CID 43855244.

- ^ "Risperdal, gynecomastia and galactorrhea in adolescent males". Allnurses.com. August 2, 2004. Retrieved September 30, 2016.

- ISBN 978-0-85369-845-6.

Withdrawal of antipsychotic drugs after long-term therapy should always be gradual and closely monitored to avoid the risk of acute withdrawal syndromes or rapid relapse.

- ^ ISBN 9780198527480.

- S2CID 6267180.

- ISBN 9788847026797.

- ISBN 978-0-521-88664-2.

- ^ a b c d e f Stahl S. Antipsychotics Explained 1 (PDF). University Psychiatry. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 7, 2017.

- ISBN 9780521886642. Retrieved September 30, 2016.

- S2CID 11800154.

- PMID 16310183.

- ^ "norepinephrine". Cardiosmart.org. December 15, 2010. Retrieved September 30, 2016.

- ISBN 9781597453110. Retrieved September 30, 2016.

- ^ "Epinephrine and Norepinephrine". Boundless.com. Archived from the original on October 13, 2016. Retrieved September 30, 2016.

- ^ "Cariprazine - Side Effects, Uses, Dosage, Overdose, Pregnancy, Alcohol". RxWiki.com. September 17, 2015. Retrieved September 30, 2016.

- ^ "INVEGA Side Effects - Schizophrenia Treatment – INVEGA (paliperidone)". Invega.com. May 17, 2016. Archived from the original on August 17, 2016. Retrieved September 30, 2016.

- ^ "Diabetes Update: Hunger is a Symptom". Diabetesupdate.blogspot.se. August 8, 2007. Retrieved September 30, 2016.

- ^ "High & Low Blood Sugar". Healthvermont.gov. Retrieved September 30, 2016.

- ^ "REXULTI (brexpiprazole) | Important Safety Information". Rexulti.com. Retrieved September 30, 2016.

- ISBN 9780521886642. Retrieved September 30, 2016.

- PMID 19086256.

- S2CID 206489515.

- ^ a b "Pharmcology Reviews : 200603" (PDF). Accessdata.fda.gov. Retrieved September 30, 2016.

- S2CID 12893717.

- ^ National Institute of Mental Health. PDSD Ki Database (Internet) [cited 2013 Aug 10]. ChapelHill (NC): University of North Carolina. 1998-2013. Available from: "PDSP Database - UNC". Archived from the original on November 8, 2013. Retrieved May 16, 2016.

- ISBN 978-1437716795. Retrieved September 30, 2016.

- ISBN 9781455728886. Retrieved September 30, 2016.

- ISBN 978-1-118-84547-9.

- ^ "FDA : Psychopharmacological Drugs Advisory Committee : Briefing Document for ZELDOX CAPSULES (Ziprasidone HCl)" (PDF). Fda.gov. July 19, 2000. Retrieved September 30, 2016.

- PMID 2842163.

- S2CID 20878941.

- PMID 19823183.

- S2CID 24251712.

- PMID 24157985.

- ^ Roth BL, Driscol J. "PDSP Ki Database". Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). University of North Carolina. Archived from the original on November 8, 2013. Retrieved October 10, 2013.

- ^ Culpepper, 2007[full citation needed]

- ^ "Medscape Multispecialty – Home page". WebMD. Retrieved November 27, 2013.[full citation needed]

- Department of Health (Australia). Retrieved November 27, 2013.[full citation needed]

- ^ "Daily Med – Home page". U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved November 27, 2013.[full citation needed]

- S2CID 23464075.

- ^ Product Information: Eunerpan(R), Melperonhydrochlorid. Knoll Deutschland GmbH, Ludwigshafen, 1995.

- S2CID 36697288.

- ^ Product Information: Nipolept(R), zotepine. Klinge Pharma GmbH, Munich, 1996.

- PMID 9485566.

- ^ Parent M, Toussaint C, Gilson H (1983). "Long-term treatment of chronic psychotics with bromperidol decanoate: clinical and pharmacokinetic evaluation". Current Therapeutic Research. 34 (1): 1–6.

- ^ PMID 6931472.

- ^ a b Reynolds JE (1993). "Anxiolytic sedatives, hypnotics and neuroleptics.". Martindale: The Extra Pharmacopoeia (30th ed.). London: Pharmaceutical Press. pp. 364–623.

- PMID 6143748.

- ^ PMID 444352.

- ^ Young D, Ereshefsky L, Saklad SR, Jann MW, Garcia N (1984). Explaining the pharmacokinetics of fluphenazine through computer simulations. (Abstract.). 19th Annual Midyear Clinical Meeting of the American Society of Hospital Pharmacists. Dallas, Texas.

- PMID 4992598.

- PMID 3545764.

- PMID 7185768.

- ^ Larsson M, Axelsson R, Forsman A (1984). "On the pharmacokinetics of perphenazine: a clinical study of perphenazine enanthate and decanoate". Current Therapeutic Research. 36 (6): 1071–88.

- PMID 16498489.

- S2CID 46319827.

- PMID 17015810.

- PMID 36821764.

- ^ "Drug Product Database Online Query". Government of Canada, Health Canada, Public Affairs, Consultation and Regions Branch. April 25, 2012. Retrieved February 1, 2018.

- ^ "Search the TGA website". Australian Government Department of Health, Therapeutic Goods Administration. Archived from the original on July 16, 2017. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- ^ a b "European Medicines Agency: Search". European Medicines Agency. Archived from the original on May 26, 2012. Retrieved February 2, 2018. Search

- ^ "Search". Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Archived from the original on November 16, 2018. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- ^ "Medicines Information: SPC & PILs". Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- ^ "Guidance: Antipsychotic medicines". Medicines & Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. August 25, 2005. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

Further reading

- Elmorsy E, Smith PA (May 2015). "Bioenergetic disruption of human micro-vascular endothelial cells by antipsychotics" (PDF). Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 460 (3): 857–62. PMID 25824037. Archived from the original(PDF) on July 22, 2018. Retrieved December 14, 2019.

- Simpson GM (September 2005). "Atypical antipsychotics and the burden of disease". The American Journal of Managed Care. 11 (8 Suppl): S235-41. PMID 16180961.

- New antipsychotic drugs carry risks for children (USA Today 2006)

- "NIMH Study to Guide Treatment Choices for Schizophrenia" (Press release). National Institute of Mental Health. September 19, 2005. Archived from the original on September 2, 2013. Retrieved August 18, 2013.

External links

Media related to Atypical antipsychotics at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Atypical antipsychotics at Wikimedia Commons