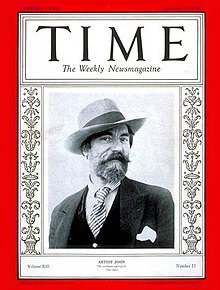

Augustus John

Augustus John RA | |

|---|---|

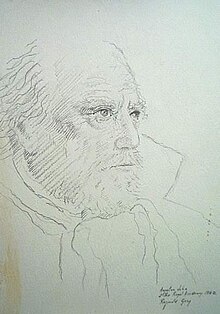

John in 1902 by George Charles Beresford | |

| Born | Augustus Edwin John 4 January 1878 Tenby, Pembrokeshire, Wales |

| Died | 31 October 1961 (aged 83) Fordingbridge, Hampshire, England |

| Known for | painter |

| Movement | Post-Impressionism |

| Spouse | |

| Partner | Royal Academician |

Augustus Edwin John

Early life

Born in

In 1897, John hit submerged rocks diving into the sea at Tenby, suffering a serious head injury; the lengthy convalescence that followed seems to have stimulated his adventurous spirit and accelerated his artistic growth.[2][8] In 1898, he won the Slade Prize with Moses and the Brazen Serpent. John afterward studied independently in Paris where he seems to have been influenced by Pierre Puvis de Chavannes.[9]

The need to support Ida Nettleship (1877–1907), whom he married in 1901, led him to accept a post teaching art at the University of Liverpool.[10]

North Wales

Over a period of two years from around 1910 Augustus John and his friend James Dickson Innes painted in the Arenig valley, in particular one of Innes's favourite subjects, the mountain Arenig Fawr. In 2011 this period was made the subject of a BBC documentary titled The Mountain That Had to Be Painted.[11]

Alderney Manor

Alderney Manor, Dorset, was sited on the Poole to Ringwood road between Knighton Bottom and Howe Corner from the early 19th century.[12] John established an artists' colony there in 1911. Faye Hammill relates how he lived there with "his five legitimate children, his mistress Dorelia McNeill, and his two children by her; and they remained there until 1927, in the company of numerous long-term guests".[13] One frequent visitor was fellow artist Henry Lamb. Aspects of John's life during this period were used as background by Margaret Kennedy in her novel The Constant Nymph (1924).[14] A housing estate now occupies the site.

Provence

In February 1910, John visited and fell in love with the town of Martigues, in Provence, located halfway between Arles and Marseilles, and first seen from a train en route to Italy.[15] John wrote that Provence "had been for years the goal of my dreams" and Martigues was the town for which he felt the greatest affection. "With a feeling that I was going to find what I was seeking, an anchorage at last, I returned from Marseilles, and, changing at Pas des Lanciers, took the little railway which leads to Martigues. On arriving my premonition proved correct: there was no need to seek further."[16] The connection with Provence continued until 1928, by which time John felt the town had lost its simple charm, and he sold his home there.[17]

John was, throughout his life, particularly interested in the Romani people (whom he referred to as "Gypsies"), and sought them out on his frequent travels around the United Kingdom and Europe, learning to speak various versions of their language. For a time, shortly after his marriage, he and his family, which included his wife Ida, mistress Dorothy (Dorelia) McNeill, and John's children by both women, travelled in a caravan, in gypsy fashion.[18] Later on he became the President of the Gypsy Lore Society, a position he held from 1937 until his death in 1961.[19]

By 1913, John was successful enough to commission a new home and studio at Mallord Street, Chelsea, from architect Robert van 't Hoff.[7]

War

In December 1917 John was attached to the Canadian forces as a war artist and made a number of memorable portraits of Canadian infantrymen. The result was to have been a huge mural for

Portraits

Although known early in the century for his drawings and

By the 1920s John was Britain's leading portrait painter. John painted many distinguished contemporaries, including

It was said that after the war his powers diminished as his bravura technique became sketchier.

Of his method for painting portraits John explained:[31]

Make a puddle of paint on your palette consisting of the predominant colour of your model's face and ranging from dark to light. Having sketched the features, being most careful of the proportions, apply a skin of paint from your preparation, only varying the mixture with enough red for the lips and cheeks and grey for the eyeballs. The latter will need touches of white and probably some blue, black, brown, or green. If you stick to your puddle (assuming that it was correctly prepared), your portrait should be finished in an hour or so, and be ready for obliteration before the paint dries, when you start afresh.

Family

On 24 January 1901 John married

By

In a 1977 interview, Caitlin Thomas was asked about her family's friendship with Augustus John and the rumors surrounding his promiscuity. When asked if John "pounced on" her, she replied, "Oh yes, constantly, and on his daughters."[36]

Later life

In later life, John wrote two volumes of autobiography, Chiaroscuro (1952) and Finishing Touches (1964).

He joined the

He is said to have been the model for the bohemian painter depicted in Joyce Cary's novel The Horse's Mouth, which was later made into a 1958 film of the same name with Alec Guinness in the lead role.

Honours and reputation

Early in his career John became a leading figure in the

Collections

His work is held in the permanent collections of many museums worldwide, including the

Bibliography

- Augustus John, Chiaroscuro - Fragments of Autobiography, Readers Union / Jonathan Cape, London, 1954.

- Augustus John, Finishing Touches, edited and introduced by Daniel George, Readers Union / Jonathan Cape, London 1966.

- Michael Holroyd, Augustus John: A Biography, London: Heinemann, 1974-1975 (2 vols.); New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1975 (1 vol.).

- Michael Holroyd, Augustus John: The New Biography, London, UK: Chatto & Windus, 1996; New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1996.

- David Boyd Haycock, Augustus John: Drawn from Life, London, UK: Paul Holberton Publishing, 2018.

- David Boyd Haycock, Brilliant Destiny: The Age of Augustus John: Drawn from Life, London, UK: Lund Humphries, 2023.

See also

- Vernon Watkins

- Marchesa Casati – Augustus John painting of Luisa Casati

References

- ^ Virginia Woolf, Moments of Being: Autobiographical Writings, edited by Jeanne Schulkind, London: Pimlico (2002), p. 56.

- ^ a b c "Wales arts: Augustus John". BBC Wales. 10 January 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- ISBN 9780415265836– via Google Books.

- ^ Easton, Malcolm, and Holroyd, Michael: The Art of Augustus John, page 1. David R. Godine, 1975.

- ^ As witness "The legendary Slade acclamation, 'There was a man sent from God, whose name was John'". Easton and Holroyd, page 2.

- ^ One of "a bevy of talented girls" there at the time. Easton and Holroyd, page 2.

- ^ a b "Settlement and building: Artists and Chelsea Pages 102-106 A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 12, Chelsea". British History Online. Victoria County History, 2004. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ Easton and Holroyd, page 2.

- ^ Easton and Holroyd, page 13.

- ^ Cole, Dani. "The last bohemian, enthralled by Liverpool". www.livpost.co.uk.

- ^ "BBC Four - The Mountain That Had to Be Painted". BBC.

- ^ In Search of Alderney Manor, Poole Museum Society

- ^ Hammill, Faye. Women, Celebrity, and Literary Culture between the Wars (2009), p. 144

- ^ Violet Powell. The Constant Novelist: a study of Margaret Kennedy, 1896-1967 (1983), pp. 57-68

- ^ Easton and Holroyd, page 64.

- ^ "'The Little Railway, Martigues', Augustus John OM, 1928". Tate.

- ^ Easton and Holroyd, page 184.

- ^ Easton and Holroyd, pages 12–13.

- ^ "The University of Liverpool ~ SC&A; ~ Home". Archived from the original on 29 January 2010. Retrieved 28 July 2010.

- ISBN 9780374102555.

- ^ Ltd, Not Panicking (18 September 2001). "h2g2 - 'Woman Smiling' - the Painting by Augustus John - Edited Entry". h2g2.com.

- ^ Easton and Holroyd, pages 26, 162.

- ^ "Duke and Duchess of Cambridge will unveil the Canadians Opposite Lens, the latest Canadian War Museum acquisition Archived 7 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine", press release via Canada NewsWire, 2 July 2011.

- ^ James Joyce complained that John's drawings of him "failed to represent accurately the lower part of his face", and commenting on Lady Ottoline Morrell's determination to hang her portrait in her drawing-room, John observed "Whatever she may have lacked, it wasn't courage." Easton and Holroyd, pages 186, 82.

- ^ "Cailtin Thomas". BBC. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ "Acquisitions of the month: August-September 2018". Apollo Magazine. 3 October 2018.

- ^ Easton and Holroyd, page 24.

- ^ The Two Jamaican Girls, by Augustus John (1878–1961)

- ^ Easton and Holroyd, page 194.

- ^ Montgomery, Bernard Law (1958). The Memoirs of Field-Marshal Montgomery. London: The Companion Book Club (Oldhams Press Ltd). pp. 216–217.

- ^ Easton and Holroyd, page 156.

- ^ Hill, Rosemary (28 June 2017). "Rosemary Hill · One's Self-Washed Drawers: Ida John · LRB 28 June 2017". London Review of Books. 39 (13).

- ^ "Obituary: Vivien John". The Independent. 27 May 1994.

- ^ Gwyneth Johnstone obituary (The Guardian, 6 January 2011).

- ^ Devine, Darren (9 March 2012). "Last illegitimate son of Augustus John on life with 'King of Bohemia'". walesonline.

- ^ https://vimeo.com/465553412.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Easton and Holroyd, pages 41–2.

- ISBN 9780900480898.

- ^ "Gwen John and Augustus John – Exhibition at Tate Britain". Tate. Retrieved 4 August 2021.

- ^ "Augustus John Artist Receives Freedom Borough His Editorial Stock Photo - Stock Image | Shutterstock". Shutterstock Editorial.

- ^ Haycock (2018), p. 11.

- ^ "Loading... | Collections Online - Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa". collections.tepapa.govt.nz. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ "Augustus JOHN - Artists - eMuseum". collections.sbma.net. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ "drawing | British Museum". The British Museum. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ "Augustus John. Alice Rothenstein. (n.d.) | MoMA". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ "Exchange: William Butler Yeats". exchange.umma.umich.edu. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ "Brooklyn Museum". www.brooklynmuseum.org. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ "Art Collections Online". Amgueddfa Cymru – Museum Wales. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ "The Mumpers". www.dia.org. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ "Philadelphia Museum of Art - Collections Object : Hope Scott". www.philamuseum.org. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

External links

- 288 artworks by or after Augustus John at the Art UK site

- Augustus John collection at the Tate Gallery Archived 17 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- Augustus John collection at the National Portrait Gallery London Archived 30 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Augustus John collection at Amgueddfa Cymru – Museum Wales

- The Dawn a symbolic war lithograph of 1917

- Augustus John - an appreciation by Colin Ward

- John's prize-winning painting Study for Moses and the Brazen Serpent

- Portraits of Elizabeth Asquith by John and others

- John's sketch of the writer, James Joyce

- John's connection with the anarchist movement from libcom.org

- Augustus John's Collection Archived 18 February 2012 at the The University of Texas at Austin