Aztec codex

Aztec codices (

.History

Before the start of the Spanish colonization of the Americas, the Mexica and their neighbors in and around the Valley of Mexico relied on painted books and records to document many aspects of their lives. Painted manuscripts contained information about their history, science, land tenure, tribute, and sacred rituals.[1] According to the testimony of Bernal Díaz del Castillo, Moctezuma had a library full of such books, known as amatl, or amoxtli, kept by a calpixqui or nobleman in his palace, some of them dealing with tribute.[2] After the conquest of Tenochtitlan, indigenous nations continued to produce painted manuscripts, and the Spaniards came to accept and rely on them as valid and potentially important records. The native tradition of pictorial documentation and expression continued strongly in the Valley of Mexico several generations after the arrival of Europeans. The latest examples of this tradition reach into the early seventeenth century.[1]

Formats

Since the 19th century, the word

Writing and pictography

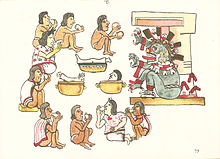

Aztec codices differ from European books in that most of their content is pictorial in nature. In regards to whether parts of these books can be considered as writing, current academics are divided in two schools: those endorsing grammatological perspectives, which consider these documents as a mixture of iconography and writing proper,[6] and those with semasiographical perspectives, which consider them a system of graphic communication which admits the presence of glyphs denoting sounds (glottography).[7] In any case, both schools coincide in the fact that most of the information in these manuscripts was transmitted by images, rather than by writing, which was restricted to names.[8]

Style and regional schools

According to Donald Robertson, the first scholar to attempt a systematic classification of Aztec pictorial manuscripts, the pre-Conquest style of Mesoamerican pictorials in Central Mexico can be defined as being similar to that of the Mixtec. This has historical reasons, for according to Codex Xolotl and historians like Ixtlilxochitl, the art of tlacuilolli or manuscript painting was introduced to the Tolteca-Chichimeca ancestors of the Tetzcocans by the Tlaoilolaques and Chimalpanecas, two Toltec tribes from the lands of the Mixtecs.[9] The Mixtec style would be defined by the usage of the native "frame line", which has the primary purpose of enclosing areas of color. as well as to qualify symbolically areas thus enclosed. Colour is usually applied within such linear boundaries, without any modeling or shading. Human forms can be divided into separable, component parts, while architectural forms are not realistic, but bound by conventions. Tridimensionality and perspective is absent. In contrast, post-Conquest codices present the use of European contour lines varying in width, and illusions of tridimensionality and perspective.[3] Later on, Elizabeth Hill-Boone gave a more precise definition of the Aztec pictorial style, suggesting the existence of a particular Aztec style as a variant of the Mixteca-Puebla style, characterized by more naturalism[10] and the use of particular calendrical glyphs that are slightly different from those of the Mixtec codices.

Regarding local schools within the Aztec pictorial style, Robertson was the first to distinguish three of them:

- School of Mexico Tenochtitlan: Based at the imperial capital of Tenochtitlan, it comprises two stages, an early one which would include the Matrícula de Tributos, Plano en Papel de Maguey, Codex Boturini and the Codex Borgia; and a later one, which would comprise Codex Mendoza, Codex Telleriano-Remensis, Codex Osuna, Codex Mexicanus and the Magliabechiano Group.

- School of Texcoco: Based at the Texcoco polity (altepetl), this school comprises documents related to the court of Nezahualcoyotl. Its foremost representativese are the Mapa Quinatzin, Mapa Tlotzin, Codex Xolotl, Codex en Cruz, the Boban Calendar Wheel, and the Relaciones Geográficas de Texcoco.

- School of Tlatelolco: Based at the sister-city of Tenochtitlan, Mapa de Santa Cruz, the Codex of Tlatelolco and the Florentine Codex.

Survival and preservation

A large number of prehispanic and colonial indigenous texts have been destroyed or lost over time. For example, when Hernan Cortés and his six hundred conquistadores landed on the Aztec land in 1519, they found that the Aztecs kept books both in temples and in libraries associated to palaces such as that of Moctezuma. For example, besides the testimony of Bernal Díaz quoted above, the conquistador Juan Cano describes some of the books to be found at the library of Moctezuma, dealing with religion, genealogies, government, and geography, lamenting their destruction at the hands of the Spaniards, for such books were essential for the government and policy of indigenous nations.[11] Further loss was caused by Catholic priests, who destroyed many of the surviving manuscripts during the early colonial period, burning them because they considered them idolatrous.[12]

The large extant body of manuscripts that did survive can now be found in museums, archives, and private collections. There has been considerable scholarly work on individual codices as well as the daunting task of classification and description. A major publication project by scholars of Mesoamerican ethnohistory was brought to fruition in the 1970s: volume 14 of the

Three Aztec codices have been considered as being possibly pre-Hispanic: Codex Borbonicus, the Matrícula de Tributos and the Codex Boturini. According to Robertson, no pre-Conquest examples of Aztec codices survived, for he considered the Codex Borbonicus and the Codex Boturini as displaying limited elements of European influence, such as the space apparently left to add Spanish glosses for calendric names in the Codex Borbonicus and some stylistic elements of trees in Codex Boturini.[3] Similarly, the Matrícula de Tributos seems to imitate European paper proportions, rather than native ones. However, Robertson's views, which equated Mixtec and Aztec style, have been contested by Elizabeth-Hill Boone, who considered a more naturalistic quality of the Aztec pictorial school. Thus, the chronological situation of these manuscripts is still disputed, with some scholars being in favour of them being prehispanic, and some against.[13]

Classification

The types of information in manuscripts fall into several categories: calendrical, historical, genealogical, cartographic, economic/tribute, economic/census and cadastral, and economic/property plans.

Another mixed alphabetic and pictorial source for Mesoamerican ethnohistory is the late sixteenth-century Relaciones geográficas, with information on individual indigenous settlements in colonial Mexico, created on the orders of the Spanish crown. Each relación was ideally to include a pictorial of the town, usually done by an indigenous resident connected with town government. Although these manuscripts were created for Spanish administrative purposes, they contain important information about the history and geography of indigenous polities.[19][20][21][22]

Important codices

Particularly important colonial-era codices that are published with scholarly English translations are Codex Mendoza, the Florentine Codex, and the works by Diego Durán. Codex Mendoza is a mixed pictorial, alphabetic Spanish manuscript.[23] Of supreme importance is the Florentine Codex, a project directed by Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún, who drew on indigenous informants' knowledge of Aztec religion, social structure, natural history, and includes a history of the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire from the Mexica viewpoint.[24] The project resulted in twelve books, bound into three volumes, of bilingual Nahuatl/Spanish alphabetic text, with illustrations by native artists; the Nahuatl has been translated into English.[25] Also important are the works of Dominican Diego Durán, who drew on indigenous pictorials and living informants to create illustrated texts on history and religion.[26]

The colonial-era codices often contain Aztec pictograms or other pictorial elements. Some are written in alphabetic text in

Some prose manuscripts in the indigenous tradition sometimes have pictorial content, such as the Florentine Codex, Codex Mendoza, and the works of Durán, but others are entirely alphabetic in Spanish or Nahuatl. Charles Gibson has written an overview of such manuscripts, and with John B. Glass compiled a census. They list 130 manuscripts for Central Mexico.[27][28] A large section at the end has reproductions of pictorials, many from central Mexico.

List of Aztec codices

- Spanish conquest.

- Francesco Barberini, who had possession of the manuscript in the early 17th century.[29]

- Chavero Codex of Huexotzingo

- Codex Osuna

- Codex Azcatitlan, a pictorial history of the Aztec empire, including images of the conquest

- Bibliothèque Nationale de France. A copy of the original is held at the Princeton University library in the Robert Garrett Collection. The Aubin Codex is not to be confused with the similarly named Aubin Tonalamatl.[30]

- Spanish conquest of Mexico. Like all pre-Columbian Aztec codices, it was originally pictorial in nature, although some Spanish descriptions were later added. It can be divided into three sections: An intricate tonalamatl, or divinatory calendar; documentation of the Mesoamerican 52-year cycle, showing in order the dates of the first days of each of these 52 solar years; and a section of rituals and ceremonies, particularly those that end the 52-year cycle, when the "new fire" must be lit. Codex Bornobicus is held at the Library of the National Assembly of France.

- Codex Borgia – pre-Hispanic ritual codex, after which the group Borgia Group is named. The codex is itself named after Cardinal Stefano Borgia, who owned it before it was acquired by the Vatican Library.

- Museo Nacional de Antropologíain Mexico City.

- Codex Chimalpahin, a collection of writings attributed to colonial-era historian Chimalpahin concerning the history of various important city-states.[31]

- Codex Chimalpopoca

- Codex Cospi, part of the Borgia Group.

- Codex Cozcatzin, a post-conquest, bound manuscript consisting of 18 sheets (36 pages) of European paper, dated 1572, although it was perhaps created later than this. Largely pictorial, it has short descriptions in Spanish and Nahuatl. The first section of the codex contains a list of land granted by Bibliothèque Nationalein Paris.

- Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris.

- Codex Fejérváry-Mayer – pre-Hispanic calendar codex, part of the Borgia Group.

- Codex Laud, part of the Borgia Group.

- tonalpohualli, the 18 monthly feasts, the 52-year cycle, various deities, indigenous religious rites, costumes, and cosmological beliefs. The Codex Magliabechiano has 92 pages made from Europea paper, with drawings and Spanish language text on both sides of each page. It is named after Antonio Magliabechi, a 17th-century Italian manuscript collector, and is held in the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, Florence, Italy.

- Codex Mendoza is a pictorial document, with Spanish annotations and commentary, composed circa 1541. It is divided into three sections: a history of each Aztec ruler and their conquests; a list of the tribute paid by each tributary province; and a general description of daily Aztec life. It is held in the Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford.[34]

- Codex Mexicanus

- Codex Osuna is a mixed pictorial and Nahuatl alphabetic text detailing complaints of particular indigenous against colonial officials.

- Codex Porfirio Díaz, sometimes considered part of the Borgia Group

- Codex Reese - a map of land claims in Tenotichlan discovered by the famed manuscript dealer William Reese.[35]

- Codex Santa Maria Asunción - Aztec census, similar to Codex Vergara; published in facsimile in 1997.[36]

- Codex Telleriano-Remensis - calendar, divinatory almanac and history of the Aztec people, published in facsimile.[37]

- Codex Ríos - an Italian translation and augmentation of the Codex Telleriano-Remensis.

- Codex of Tlatelolco is a pictorial codex, produced around 1560.

- Codex Vaticanus B, part of the Borgia Group

- Codex Vergara - records the border lengths of Mesoamerican farms and calculates their areas.[38]

- Texcoco in particular, from Xolotl's arrival in the Valley to the defeat of Azcapotzalco in 1428.[39]

- Hernando Alvarado Tezozomoc, prose manuscript in the native tradition.

- Arthur J.O. Andersonpublished English translations of the Nahuatl text of the twelve books in separate volumes, with redrawn illustrations. A full color, facsimile copy of the complete codex was published in three bound volumes in 1979.

- Nahua pictorials that are part of a 1531 lawsuit by Hernán Cortés against Nuño de Guzmánthat the Huexotzincans joined.

- Mapa de Cuauhtinchan No. 2 - a post-conquest indigenous map, legitimizing the land rights of the Cuauhtinchantlacas.

- Texcoco. It has valuable information on the Texcocan legal system, depicting particular crimes and the specified punishments, including adultery and theft. One striking fact is that a judge was executed for hearing a case that concerned his own house. It has name glyphs for Nezahualcoyotal and his successor Nezahualpilli.[40]

- Matrícula de Huexotzinco. Nahua pictorial census and alphabetic text, published in 1974.[41]

- Texcoco ca. 1540 relative to the estate of Don Carlos Chichimecatecatlof Texcoco.

- Codex Ramírez - a history by Juan de Tovar.

- Romances de los señores de Nueva España - a collection of Nahuatl songs transcribed in the mid-16th century

- Santa Cruz Map. Mid-sixteenth-century pictorial of the area around the central lake system.[42]

- Codices of San Andrés Tetepilco

- Map of the Founding of Tetepilco, found in 2024, "about the foundation of San Andrés Tetepilco and includes lists of toponyms within the region"[43]

- Inventory of the Church of San Andrés Tetepilco, found in 2024, "a pictographic inventory of the church and its assets"[43]

- Tira of San Andrés Tetepilco, history of Tenochtitlan from foundation to 17th century[43]

Legacy

Continued scholarship of the codices has been influential in contemporary Mexican society, particularly for contemporary Nahuas who are now reading these texts to gain insight into their own histories.[44][45] Research on these codices has also been influential in Los Angeles, where there is a growing interest in Nahua language and culture in the 21st century.[46][47]

See also

- Mixtec codices. Codex Zouche-Nuttall is in the British Museum.

- Crónica X

- Historia de Mexico with the Tovar calendar, ca. 1830–1862. From the Jay I Kislak Collection at the Library of Congress

- Maya codices

- Mesoamerican literature

- Colonial Mesoamerican native-language texts

References

- ^ ISBN 9780195188431

- OCLC 1145170261.

- ^ OCLC 30436784.

- ^ Article in Mexicolore

- OCLC 1101345811.

- ISSN 2448-5179.

- )

- OCLC 768827325.

- OCLC 18797818.

- OCLC 3843930.

- OCLC 122937827.

- ISBN 9781628733228.

- )

- ^ Glass, John B. "A Survey of Native Middle American Pictorial Manuscripts", article 22, Guide to Ethnohistorical Sources Part 3; Handbook of Middle American Indians. University of Texas Press 1975, pp. 3-80.

- ^ Glass, John B. in collaboration with Donald Robertson. "A Census of Native Middle American Pictorial Manuscripts". article 23, Guide to Ethnohistorical Sources Part 3; Handbook of Middle American Indians. University of Texas Press 1975, pp. 81-252.

- ^ Robertson, Donald. "Techialoyan Manuscripts and Paintings with a Catalog." article 24, Guide to Ethnohistorical Sources Part 3; Handbook of Middle American Indians. University of Texas Press 1975, pp. 253-281.

- ^ Glass, John B. "A Census of Middle American Testerian Manuscripts." article 25, Guide to Ethnohistorical Sources Part 3; Handbook of Middle American Indians. University of Texas Press 1975, pp. 281-296.

- ^ Glass, John B. "A Catalog of Falsified Middle American Pictorial Manuscripts." article 26, Guide to Ethnohistorical Sources Part 3; Handbook of Middle American Indians. University of Texas Press 1975, pp. 297-309.

- ISBN 0-292-70152-7

- ^ Robertson, Donald, "The Pinturas (Maps) of the Relaciones Geográficas, with a Catalog", article 6.Guide to Ethnohistorical Sources Part 1; Handbook of Middle American Indians. University of Texas Press 1972, pp. 243-278.

- ^ Cline, Howard F. "A Census of the Relaciones Geográficas of New Spain, 1579-1612," article 8. Guide to Ethnohistorical Sources Part 1; Handbook of Middle American Indians. University of Texas Press 1972, pp. 324-369.

- ^ Mundy, Barbara E. The Mapping of New Spain: Indigenous Cartography and the Maps of the Relaciones Geográficas. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996.

- ^ Berdan, Frances, and Patricia Rieff Anawalt. The Codex Mendoza. 4 vols. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992.

- ^ Sahagún, Bernardino de. El Códice Florentino: Manuscrito 218-20 de la Colección Palatina de la Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana. Fascimile ed., 3 vols. Florence: Giunti Barbera and México: Secretaría de Gobernación, 1979.

- ^ Sahagún, Bernardino de. General History of the Things of New Spain: Florentine Codex. Translated by Arthur J. O Anderson and Charles E Dibble. 13 vols. Monographs of the School of American Research 14. Santa Fe: School of American Research; Salt Lake City: University of Utah, 1950-82.

- ^ Durán, Diego. The History of the Indies of New Spain. Translated by Doris Heyden. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1994. Durán, Diego. Book of the Gods and Rites and the Ancient Calendar. Translated by Fernando Horcasitas and Doris Heyden. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1971.

- ^ Gibson, Charles. "Prose sources in the Native Historical Tradition", article 27B. "A Census of Middle American Prose Manuscripts in the Native Historical Tradition". Guide to Ethnohistorical Sources Part 4; Handbook of Middle American Indians. University of Texas Press 1975, 326-378.

- ^ Gibson, Charles and John B. Glass. "Prose sources in the Native Historical Tradition", article 27A. "A Survey of Middle American Prose Manuscripts in the Native Historical Tradition". Guide to Ethnohistorical Sources Part 4; Handbook of Middle American Indians. University of Texas Press 1975, 311-321.

- ISBN 978-0486-41130-9

- ^ Aubin Tonalamatl, Trafficking Culture Encyclopedia

- ^ Codex Chimalpahin: Society and Politics in Mexico-Tenochtitlan, Tlatelolco, Texcoco, Culhuacan, and other Nahua Altepetl in Central Mexico. Domingo de San Antón Muñon Chimalpahin Cuauhtlehuantzin, Edited and translated by Arthur J.O. Anderson, et al. 2 vols. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press 1997.

- ^ Jacqueline de Durand-Forest, ed. Codex Ixtlilxochitl: Bibliothèque nationale, Paris (Ms. Mex. 55-710). Fontes rerum Mexicanarum 8. Graz, Austria: Akademische Druck- und Verlagsanstalt 1976.

- ^ "FAMSI - Akademische Druck - u. Verlagsanstalt - Graz - Codex Ixtlilxochitl".

- ISBN 978-0520-20454-6

- ^ Raymond, Lindsey (2010-09-24). "One man, 65,000 manuscripts". Yale Daily News. Retrieved 2022-04-24.

- ISBN 0-87480-522-8

- ISBN 978-0-292-76901-4.

- ^ M. Jorge et al. (2011). Mathematical accuracy of Aztec land surveys assessed from records in the Codex Vergara. PNAS: University of Michigan.

- S2CID 161510221.

- ISBN 978-0521-23475-7

- ISBN 978-3201-00870-9

- ^ Sigvald Linné, El valle y la ciudad de México en 1550. Relación histórica fundada sobre un mapa geográfico, que se conserva en la biblioteca de la Universidad de Uppsala, Suecia. Stockholm: 1948.

- ^ a b c "Archaeologists recover 16th-century Aztec codices of San Andrés Tetepilco". 22 March 2024.

- ^ Tenorio, Rich (2021-10-07). "Scholar says 'underestimated' Mexica writing system deserves respect". Mexico News Daily. Retrieved 2023-01-21.

- ^ "Aztec renaissance: New research sheds fresh light on intellectual achievements of long-vanished empire". The Independent. 2021-04-08. Retrieved 2023-01-21.

- ^ "UCLA historian brings language of the Aztecs from ancient to contemporary times". UCLA. Retrieved 2023-01-21.

- ^ Mattei, Shanti Escalante-De (2022-02-18). "LACMA Exhibits Subvert the Totalizing Myths of Colonial Conquest". ARTnews.com. Retrieved 2023-01-21.

Further reading

- Batalla Rosado, Juan José. "The Historical Sources: Codices and Chronicles" in The Oxford Handbook of the Aztecs. Oxford University Press 2017, pp. 29–40. ISBN 978-0-19-934196-2

- ISBN 0-292-70152-7

- ISBN 0-292-70152-7

- ISBN 0-292-70154-3

- ISBN 0-292-70154-3

- ISBN 0-292-70153-5

- Glass, John B. "A Survey of Native Middle American Pictorial Manuscripts", article 22, Guide to Ethnohistorical Sources Part 3; ISBN 0-292-70154-3

- Glass, John B. "A Census of Middle American Testerian Manuscripts." article 25, Guide to Ethnohistorical Sources Part 3; ISBN 0-292-70154-3

- Glass, John B. "A Catalog of Falsified Middle American Pictorial Manuscripts." article 26, Guide to Ethnohistorical Sources Part 3; ISBN 0-292-70154-3

- Glass, John B. in collaboration with Donald Robertson. "A Census of Native Middle American Pictorial Manuscripts". article 23, Guide to Ethnohistorical Sources Part 3; ISBN 0-292-70154-3

- Nicholson, H. B. “Pre-Hispanic Central Mexican Historiography.” In Investigaciones contemporáneos sobre historia de México. Memorias de la tercera reunión de historiadores mexicanos y norteamericanos, Oaxtepec, Morelos, 4–7 de noviembre de 1969, pp. 38–81. Mexico City, 1971.

- Robertson, Donald, "The Pinturas (Maps) of the Relaciones Geográficas, with a Catalog", article 6.Guide to Ethnohistorical Sources Part 1; ISBN 0-292-70152-7

- Robertson, Donald. "Techialoyan Manuscripts and Paintings with a Catalog." article 24, Guide to Ethnohistorical Sources Part 3; ISBN 0-292-70154-3