BBC

Logo used since 2021 | |

| Company type | Statutory corporation with a royal charter, Public broadcasting[a] |

|---|---|

| Industry | Mass media |

| Predecessor | British Broadcasting Company |

| Founded | 18 October 1922 (as British Broadcasting Company) 1 January 1927 (as British Broadcasting Corporation) |

| Founder | HM Government |

| Headquarters | Broadcasting House, London |

Area served | Worldwide |

Key people |

|

| Products |

|

| Services | |

| Revenue | |

| Total assets | |

Number of employees | |

| Divisions | |

| Website | bbc |

| BBC |

|---|

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved into its current state with its current name on New Year's Day 1927. The oldest and largest local and global broadcaster by stature and by number of employees, the BBC employs over 21,000 staff in total, of whom approximately 17,900 are in public-sector broadcasting.[3][4][5][6][7]

The BBC was established under a

Some of the BBC's revenue comes from its commercial subsidiary

Since its formation in 1922, the BBC has played a prominent role in British life and culture.[16] It is colloquially known as the Beeb or Auntie.[17][18]

History

The birth of British broadcasting, 1920 to 1922

Britain's first live public broadcast was made from the factory of

But by 1922, the GPO had received nearly 100 broadcast licence requests

From private company towards public service corporation, 1923 to 1926

The financial arrangements soon proved inadequate. Set sales were disappointing as amateurs made their own receivers and listeners bought rival unlicensed sets.[19]: 146 By mid-1923, discussions between the GPO and the BBC had become deadlocked and the Postmaster General commissioned a review of broadcasting by the Sykes Committee.[25] The committee recommended a short-term reorganisation of licence fees with improved enforcement in order to address the BBC's immediate financial distress, and an increased share of the licence revenue split between it and the GPO. This was to be followed by a simple 10 shillings licence fee to fund broadcasts.[25] The BBC's broadcasting monopoly was made explicit for the duration of its current broadcast licence, as was the prohibition on advertising. To avoid competition with newspapers, Fleet Street persuaded the government to ban news bulletins before 7 pm and the BBC was required to source all news from external wire services.[25]

Mid-1925 found the future of broadcasting under further consideration, this time by the Crawford committee. By now, the BBC, under Reith's leadership, had forged a consensus favouring a continuation of the unified (monopoly) broadcasting service, but more money was still required to finance rapid expansion. Wireless manufacturers were anxious to exit the loss-making consortium, and Reith was keen that the BBC be seen as a public service rather than a commercial enterprise. The recommendations of the Crawford Committee were published in March the following year and were still under consideration by the GPO when the

The crisis placed the BBC in a delicate position. On the one hand Reith was acutely aware that the government might exercise its right to commandeer the BBC at any time as a mouthpiece of the government if the BBC were to step out of line, but on the other he was anxious to maintain public trust by appearing to be acting independently. The government was divided on how to handle the BBC, but ended up trusting Reith, whose opposition to the strike mirrored the PM's own. Although Winston Churchill in particular wanted to commandeer the BBC to use it "to the best possible advantage", Reith wrote that Stanley Baldwin's government wanted to be able to say "that they did not commandeer [the BBC], but they know that they can trust us not to be really impartial".[26] Thus the BBC was granted sufficient leeway to pursue the government's objectives largely in a manner of its own choosing. The resulting coverage of both striker and government viewpoints impressed millions of listeners who were unaware that the PM had broadcast to the nation from Reith's home, using one of Reith's soundbites inserted at the last moment,[clarification needed] or that the BBC had banned broadcasts from the Labour Party and delayed a peace appeal by the Archbishop of Canterbury. Supporters of the strike nicknamed the BBC the BFC for British Falsehood Company. Reith personally announced the end of the strike which he marked by reciting from Blake's "Jerusalem" signifying that England had been saved.[27]

While the BBC tends to characterise its coverage of the general strike by emphasising the positive impression created by its balanced coverage of the views of government and strikers, Seaton has characterised the episode as the invention of "modern propaganda in its British form".[20]: 117 Reith argued that trust gained by 'authentic impartial news' could then be used. Impartial news was not necessarily an end in itself.[20]: 118

The BBC did well out of the crisis, which cemented a national audience for its broadcasting, and it was followed by the Government's acceptance of the recommendation made by the Crawford Committee (1925–26) that the British Broadcasting Company be replaced by a non-commercial, Crown-chartered organisation: the British Broadcasting Corporation.

1927 to 1939

The British Broadcasting Corporation came into existence on 1 January 1927, and Reith – newly knighted – was appointed its first Director General. To represent its purpose and (stated) values, the new corporation adopted the coat of arms, including the motto "Nation shall speak peace unto Nation".[30]

British radio audiences had little choice apart from the upscale programming of the BBC. Reith, an intensely moralistic executive, was in full charge. His goal was to broadcast "All that is best in every department of human knowledge, endeavour and achievement.... The preservation of a high moral tone is obviously of paramount importance."[31] Reith succeeded in building a high wall against an American-style free-for-all in radio in which the goal was to attract the largest audiences and thereby secure the greatest advertising revenue. There was no paid advertising on the BBC; all the revenue came from a tax on receiving sets. Highbrow audiences, however, greatly enjoyed it.[32] At a time when American, Australian and Canadian stations were drawing huge audiences cheering for their local teams with the broadcast of baseball, rugby and hockey, the BBC emphasised service for a national rather than a regional audience. Boat races were well covered along with tennis and horse racing, but the BBC was reluctant to spend its severely limited air time on long football or cricket games, regardless of their popularity.[33]

John Reith and the BBC, with support from

Throughout the 1930s, political broadcasts had been closely monitored by the BBC.

Experimental television broadcasts were started in 1929, using an electromechanical 30-line system developed by

BBC versus other media

The success of broadcasting provoked animosities between the BBC and well-established media such as theatres, concert halls and the recording industry. By 1929, the BBC complained that the agents of many comedians refused to sign contracts for broadcasting, because they feared it harmed the artist "by making his material stale" and that it "reduces the value of the artist as a visible music-hall performer". On the other hand, the BBC was "keenly interested" in a cooperation with the recording companies who "in recent years ... have not been slow to make records of singers, orchestras, dance bands, etc. who have already proved their power to achieve popularity by wireless." Radio plays were so popular that the BBC had received 6,000 manuscripts by 1929, most of them written for stage and of little value for broadcasting: "Day in and day out, manuscripts come in, and nearly all go out again through the post, with a note saying 'We regret, etc.'"[44] In the 1930s music broadcasts also enjoyed great popularity, for example the friendly and wide-ranging BBC Theatre Organ broadcasts at St George's Hall, London by Reginald Foort, who held the official role of BBC Staff Theatre Organist from 1936 to 1938.[45]

Second World War

Television broadcasting was suspended from 1 September 1939 to 7 June 1946, during the

During his role as prime minister during the war, Winston Churchill delivered 33 major wartime speeches by radio, all of which were carried by the BBC within the UK.[47] On 18 June 1940, French general Charles de Gaulle, in exile in London as the leader of the Free French, made a speech, broadcast by the BBC, urging the French people not to capitulate to the Nazis.[48] In October 1940, Princesses Elizabeth and Margaret made their first radio broadcast for the BBC's Children's Hour, addressing other children who had been evacuated from cities.[49]

In 1938, John Reith and the

Later 20th century

There was a widely reported urban myth that, upon resumption of the BBC television service after the war, announcer Leslie Mitchell started by saying, "As I was saying before we were so rudely interrupted ..." In fact, the first person to appear when transmission resumed was Jasmine Bligh and the words said were "Good afternoon, everybody. How are you? Do you remember me, Jasmine Bligh ... ?"[59] The European Broadcasting Union was formed on 12 February 1950, in Torquay with the BBC among the 23 founding broadcasting organisations.[60]

Competition to the BBC was introduced in 1955, with the commercial and independently operated television network of

Starting in 1964, a series of

In 1974, the BBC's

The

2000 to 2011

In 2002, several television and radio channels were reorganised. BBC Knowledge was replaced by

The following few years resulted in repositioning of some channels to conform to a larger brand: in 2003, BBC Choice was replaced by

During this decade, the corporation began to sell off a number of its operational divisions to private owners; BBC Broadcast was spun off as a separate company in 2002,

The 2004 Hutton Inquiry and the subsequent report raised questions about the BBC's journalistic standards and its impartiality. This led to resignations of senior management members at the time including the then Director General, Greg Dyke. In January 2007, the BBC released minutes of the board meeting which led to Greg Dyke's resignation.[80]

Unlike the other departments of the BBC, the BBC World Service was funded by the

A strike in 2005 by more than 11,000 BBC workers, over a proposal to cut 4,000 jobs, and to privatise parts of the BBC, disrupted much of the BBC's regular programming.[81][82]

In 2006,

On 18 October 2007, BBC Director General Mark Thompson announced a controversial plan to make major cuts and reduce the size of the BBC as an organisation. The plans included a reduction in posts of 2,500; including 1,800 redundancies, consolidating news operations, reducing programming output by 10% and selling off the flagship

On 20 October 2010, the Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne announced that the television licence fee would be frozen at its current level until the end of the current charter in 2016. The same announcement revealed that the BBC would take on the full cost of running the BBC World Service and the BBC Monitoring service from the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, and partially finance the Welsh broadcaster S4C.[84]

2011 to present

Further cuts were announced on 6 October 2011, so the BBC could reach a total reduction in their budget of 20%, following the licence fee freeze in October 2010, which included cutting staff by 2,000 and sending a further 1,000 to the

Under the new royal charter instituted in 2017, the corporation must publish an annual report to Ofcom, outlining its plans and public service obligations for the next year. In its 2017–18 report, released July 2017, the BBC announced plans to "re-invent" its output to better compete against commercial streaming services such as

In 2016, the BBC Director General Tony Hall announced a savings target of £800 million per year by 2021, which is about 23% of annual licence fee revenue. Having to take on the £700 million cost for free TV licences for the over-75 pensioners, and rapid inflation in drama and sport coverage costs, was given as the reason. Duplication of management and content spending would be reduced, and there would be a review of BBC News.[94][95]

In September 2019, the BBC launched the Trusted News Initiative to work with news and social media companies to combat disinformation about national elections.[96][97]

In 2020, the BBC announced a BBC News savings target of £80 million per year by 2022, involving about 520 staff reductions. The BBC's director of news and current affairs Fran Unsworth said there would be further moves toward digital broadcasting, in part to attract back a youth audience, and more pooling of reporters to stop separate teams covering the same news.[98][99] In 2020, the BBC reported a £119 million deficit because of delays to cost reduction plans, and the forthcoming ending of the remaining £253 million funding towards pensioner licence fees would increase financial pressures.[100]

In January 2021, it was reported that former banker

In March 2023, the BBC was at the centre of a political row with football pundit Gary Lineker, after he criticised the British government's asylum policy on social media. Lineker was suspended from his position on Match of the Day before being re-instated after receiving overwhelming support from his colleagues. The scandal was made worse due to the connections between BBC's chairman, Richard Sharp, and the Conservative Party.[102]

In April 2023, Richard Sharp resigned as chairman after a report found he did not disclose potential perceived conflicts of interest in his role in the facilitation of a loan to Prime Minister Boris Johnson.[103][104] Dame Elan Closs Stephens was appointed as acting chairwoman on 27 June 2023, and she would lead the BBC board for a year or until a new permanent chair has been appointed.[105] Samir Shah was subsequently appointed with effect from 4 March 2024.[106]

Governance

The BBC is a statutory corporation, independent from direct government intervention, with its activities being overseen from April 2017 by the BBC Board and regulated by Ofcom.[107][108] The chairman is Samir Shah.[106]

Charter and Agreement

The BBC is a state owned public broadcasting company and operates under a royal charter. The charter is the constitutional basis for the BBC, and sets out the BBC's Object, Mission and Public Purposes.[109] It emphasises public service, (limited)[b] editorial independence, prohibits advertising on domestic services and proclaims the BBC is to "seek to avoid adverse impacts on competition which are not necessary for the effective fulfilment of the Mission and the promotion of the Public Purposes".[111]

The charter also sets out that the BBC is subject to an additional 'Agreement' between it and the Culture Secretary, and that its operating licence is to be set by Ofcom, an external regulatory body. It used to be that the Home Secretary be departmental to both Agreement as well as Licence, and regulatory duties fall to the BBC Trust, but the 2017 charter changed those 2007 arrangements.[112]

The charter, too, outlines the Corporation's governance and regulatory arrangements as a statutory corporation, including the role and composition of the BBC Board. The current Charter began on 1 January 2017 and ends on 31 December 2027; the Agreement being coterminous.[109]

BBC Board

The BBC Board was formed in April 2017. It replaced the previous governing body, the BBC Trust, which itself had replaced the board of governors in 2007. The board sets the strategy for the corporation, assesses the performance of the BBC's executive board in delivering the BBC's services, and appoints the director-general. Ofcom is responsible for the regulation of the BBC. The board consists of the following members:[113][114]

| Name | Position | Term of office | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dame Elan Closs Stephens, DBE | Acting Chairwoman

|

27 June 2023 | 27 June 2024[note 1] |

| Member for Wales | 20 July 2017 | 19 July 2020 | |

| 20 January 2021 | 20 July 2023 | ||

| Tim Davie, CBE | Director-General | 1 September 2020 | — |

| Nicholas Serota, CH | Senior Independent Director | 3 April 2017 | 2 April 2024 |

| Shumeet Banerji | Non-executive Director | 1 January 2022 | 31 December 2025 |

| Sir Damon Buffini | Non-executive Director and Deputy Chair[note 2] | 1 January 2022 | 31 December 2025 |

| Shirley Garrood | Non-executive Director | 3 July 2019 | 2 July 2023 |

| Ian Hargreaves, CBE | Non-executive Director | 2 April 2020 | 2 April 2023 |

| Sir Robbie Gibb | Member for England | 7 May 2021 | 6 May 2024 |

| Muriel Gray | Member for Scotland | 3 January 2022 | 2 January 2026 |

| To be appointed by the Northern Ireland Executive | Member for Northern Ireland | — | — |

| Charlotte Moore | Chief Content Officer | 1 September 2020 | 1 September 2022 |

| 1 September 2022 | 31 August 2024 | ||

| Leigh Tavaziva | Chief Operating Officer | 1 February 2021 | 31 January 2025 |

| Deborah Turness | CEO, BBC News and Current Affairs | 5 September 2022 | 4 September 2024 |

- ^ Appointed for a year or until a new permanent chair has been appointed.[115]

- ^ The title of deputy chair is an honorary one held ex-officio by the chair of the BBC's Commercial Board[116]

Executive committee

The executive committee is responsible for the day-to-day operations of the broadcaster. Consisting of senior managers of the BBC, the committee meets once per month and is responsible for operational management and delivery of services within a framework set by the board, and is chaired by the director-general, currently Tim Davie, who is chief executive and (from 1994) editor-in-chief.[117]

| Name | Position |

|---|---|

| Tim Davie | Director-general (chair) |

| Kerris Bright | Chief Customer Officer |

| Alan Dickson | Chief Financial Officer |

| Tom Fussell | CEO, BBC Studios |

| Leigh Tavaziva | Chief Operating Officer |

| Charlotte Moore | Chief Content Officer |

| Uzair Qadeer | Chief People Officer |

| Alice Macandrew | Group Corporate Affairs Director |

| Rhodri Talfan Davies | Director, Nations |

| Gautam Rangarajan | Group Director of Strategy and Performance |

| Deborah Turness | CEO, BBC News and Current Affairs |

Operational divisions

The corporation has the following in-house divisions covering the BBC's output and operations:[118][119]

- Content, headed by Charlotte Moore is in charge of the corporation's television channels including the commissioning of programming.

- Nations and Regions, headed by Rhodri Talfan Davies is responsible for the corporation's divisions in Scotland, Northern Ireland, Wales, and the English Regions.

Commercial divisions

The BBC also operates a number of wholly owned commercial divisions:

- BBC Studios is the former in-house television production; Entertainment, Music & Events, Factual and Scripted (drama and comedy). Following a merger with BBC Worldwide in April 2018, it also operates international channels and sells programmes and merchandise in the UK and abroad to gain additional income that is returned to BBC programmes. It is kept separate from the corporation due to its commercial nature.

- BBC World Newsdepartment is in charge of the production and distribution of its commercial global television channel. It works closely with the BBC News group, but is not governed by it, and shares the corporation's facilities and staff. It also works with BBC Studios, the channel's distributor.

- BBC Studioworks is also separate and officially owns and operates some of the BBC's studio facilities, such as the BBC Elstree Centre, leasing them out to productions from within and outside of the corporation.[120]

MI5 vetting policy

From as early as the 1930s until the 1990s, MI5, the British domestic intelligence service, engaged in the vetting of applicants for BBC jobs, a policy designed to keep out persons deemed subversive.[121][122] In 1933, BBC executive Colonel Alan Dawnay began to meet the head of MI5, Sir Vernon Kell, to informally trade information; from 1935, a formal arrangement was made whereby job applicants would be secretly vetted by MI5 for their political views (without their knowledge).[121] The BBC took up a policy of denying any suggestion by the press of such a relationship (the very existence of MI5 itself was not officially acknowledged until the Security Service Act 1989).[121]

This relationship garnered wider public attention after an article by

In October 1985, the BBC announced that it would stop the vetting process, except for a few people in top roles, as well as those in charge of

Finances

The BBC has the second largest budget of any UK-based broadcaster with an operating expenditure of £4.722 billion in 2013/14

Revenue

The principal means of funding the BBC is through the television licence, costing £169.50 per year per household since April 2024.[127] Such a licence is required to legally receive broadcast television across the UK, the Channel Islands and the Isle of Man. No licence is required to own a television used for other means, or for sound only radio sets (though a separate licence for these was also required for non-TV households until 1971). The cost of a television licence is set by the government and enforced by the criminal law. A discount is available for households with only black-and-white television sets. A 50% discount is also offered to people who are registered blind or severely visually impaired,[128] and the licence is completely free for any household containing anyone aged 75 or over. However, from August 2020, the licence fee will only be waived if over 75 and receiving pension credit.[129]

The BBC pursues its licence fee collection and enforcement under the trading name "TV Licensing". The revenue is collected privately by Capita, an outside agency, and is paid into the central government Consolidated Fund, a process defined in the Communications Act 2003. Funds are then allocated by the Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) and the Treasury and approved by Parliament via legislation. Additional revenues are paid by the Department for Work and Pensions to compensate for subsidised licences for eligible over-75-year-olds.

The licence fee is classified as a tax,[130] and its evasion is a criminal offence. Since 1991, collection and enforcement of the licence fee has been the responsibility of the BBC in its role as TV Licensing Authority.[131] The BBC carries out surveillance (mostly using subcontractors) on properties (under the auspices of the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act 2000) and may conduct searches of a property using a search warrant.[132] According to TV Licensing, 216,900 people in the UK were caught watching TV without a licence in 2018/19.[133] Licence fee evasion makes up around one-tenth of all cases prosecuted in magistrates' courts, representing 0.3% of court time.[134]

Income from commercial enterprises and from overseas sales of its catalogue of programmes has substantially increased over recent years,[135] with BBC Worldwide contributing some £243 million to the BBC's core public service business.[136]

According to the BBC's 2018/19 Annual Report, its total income was £4.889 billion a decrease from £5.062 billion in 2017/18 – partly owing to a 3.7% phased reduction in government funding for free over-75s TV licences,[136] which can be broken down as follows:

- £3.690 billion in licence fees collected from householders;

- £1.199 billion from the BBC's commercial businesses and government grants some of which will cease in 2020

The licence fee has, however, attracted criticism. It has been argued that in an age of multi-stream, multi-channel availability, an obligation to pay a licence fee is no longer appropriate. The BBC's use of private sector company

The BBC uses advertising campaigns to inform customers of the requirement to pay the licence fee. Past campaigns have been criticised by Conservative MP Boris Johnson and former MP Ann Widdecombe for having a threatening nature and language used to scare evaders into paying.[138][139] Audio clips and television broadcasts are used to inform listeners of the BBC's comprehensive database.[140] There are a number of pressure groups campaigning on the issue of the licence fee.[141]

The majority of the BBC's commercial output comes from its commercial arm BBC Worldwide which sell programmes abroad and exploit key brands for merchandise. Of their 2012/13 sales, 27% were centred on the five key "superbrands" of Doctor Who, Top Gear, Strictly Come Dancing (known as Dancing with the Stars internationally), the BBC's archive of natural history programming (collected under the umbrella of BBC Earth) and the (now sold) travel guide brand Lonely Planet.[142]

Assets

Broadcasting House in Portland Place, central London, is the official headquarters of the BBC. It is home to six of the ten BBC national radio networks, BBC Radio 1, BBC Radio 1xtra, BBC Asian Network, BBC Radio 3, BBC Radio 4, and BBC Radio 4 Extra. It is also the home of BBC News, which relocated to the building from BBC Television Centre in 2013. On the front of the building are statues of Prospero and Ariel, characters from William Shakespeare's play The Tempest, sculpted by Eric Gill. Renovation of Broadcasting House began in 2002, and was completed in 2012.[143]

Until it closed at the end of March 2013,

As part of a major reorganisation of BBC property, the entire BBC News operation relocated from the News Centre at BBC Television Centre to the refurbished Broadcasting House to create what is being described as "one of the world's largest live broadcast centres".

In addition to the scheme above, the BBC is in the process of making and producing more programmes outside London, involving production centres such as

As well as the two main sites in London (Broadcasting House and White City), there are seven other important BBC production centres in the UK, mainly specialising in different productions.

Previously, the largest hub of BBC programming from the

The BBC also operates several news gathering centres in various locations around the world, which provide news coverage of that region to the national and international news operations.

Information technology service management

In 2004, the BBC contracted out its former BBC Technology division to the German engineering and electronics company

Services

Television

The BBC operates several television channels nationally and internationally. BBC One and BBC Two are the flagship television channels. Others include the youth channel BBC Three ,[c][158] cultural and documentary channel BBC Four, the British and international variations of the BBC News channel, parliamentary channel BBC Parliament, and two children's channels, CBBC and CBeebies. Digital television is now entrenched in the UK, with analogue transmission completely phased out as of December 2012[update].[159]

BBC One is a regionalised TV service which provides opt-outs throughout the day for local news and other local programming. These variations are more pronounced in the BBC "Nations", i.e.

A new Scottish Gaelic television channel, BBC Alba, was launched in September 2008. It is also the first multi-genre channel to come entirely from Scotland with almost all of its programmes made in Scotland. The service was initially only available via satellite but since June 2011 has been available to viewers in Scotland on Freeview and cable television.[161]

The BBC currently operates

In the Republic of Ireland, Belgium, the Netherlands and Switzerland, the BBC channels are available in a number of ways. In these countries digital and cable operators carry a range of BBC channels. These include BBC One, BBC Two, BBC Four and BBC World News, although viewers in the Republic of Ireland may receive BBC services via overspill from transmitters in Northern Ireland or Wales, or via "deflectors"—transmitters in the Republic which rebroadcast broadcasts from the UK,[164] received off-air, or from digital satellite.

Since 1975, the BBC has also provided its TV programmes to the

Since 2008, all the BBC channels are available to watch online through the BBC iPlayer service. This online streaming ability came about following experiments with live streaming, involving streaming certain channels in the UK.[165] In February 2014, Director-General Tony Hall announced that the corporation needed to save £100 million. In March 2014, the BBC confirmed plans for BBC Three to become an internet-only channel.[166]

BBC Genome Project

In December 2012, the BBC completed a digitisation exercise, scanning the listings of all BBC programmes from an entire run of about 4,500 copies of the Radio Times magazine from the first, 1923, issue to 2009 (later listings already being held electronically), the "BBC Genome project", with a view to creating an online database of its programme output.[167] An earlier ten months of listings are to be obtained from other sources.[167] They identified around five million programmes, involving 8.5 million actors, presenters, writers and technical staff.[167] The Genome project was opened to public access on 15 October 2014, with corrections to OCR errors and changes to advertised schedules being crowdsourced.[168]

Radio

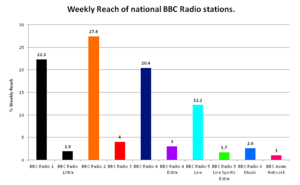

The BBC has ten radio stations serving the whole of the UK, a further seven stations in the "national regions" (Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland), and 39 other local stations serving defined areas of England. Of the ten national stations, five are major stations and are available on FM or AM as well as on DAB and online. These are BBC Radio 1, offering new music and popular styles and being notable for its chart show; BBC Radio 2, playing Adult contemporary, country and soul music amongst many other genres; BBC Radio 3, presenting classical and jazz music together with some spoken-word programming of a cultural nature in the evenings; BBC Radio 4, focusing on current affairs, factual and other speech-based programming, including drama and comedy; and BBC Radio 5 Live, broadcasting 24-hour news, sport and talk programmes.

In addition to these five stations, the BBC runs a further five stations that broadcast on DAB and online only. These stations supplement and expand on the big five stations, and were launched in 2002. BBC Radio 1Xtra sisters Radio 1, and broadcasts new black music and urban tracks. BBC Radio 5 Sports Extra sisters 5 Live and offers extra sport analysis, including broadcasting sports that previously were not covered. BBC Radio 6 Music offers alternative music genres and is notable as a platform for new artists.

As well as the national stations, the BBC also provides 40

The BBC's UK national channels are also broadcast in the Channel Islands and the Isle of Man (although these

For a worldwide audience, the

Historically, the BBC was the only legal radio broadcaster based in the UK mainland until 1967, when

BBC programming is also available to other services and in other countries. Since 1943, the BBC has provided radio programming to the

The BBC is a patron of The Radio Academy.[176]

News

BBC News is the largest broadcast news gathering operation in the world,

Ratings figures suggest that during major incidents such as the 7 July 2005 London bombings or royal events, the UK audience overwhelmingly turns to the BBC's coverage as opposed to its commercial rivals.[178] On 7 July 2005, the day that there were a series of coordinated bomb blasts on London's public transport system, the BBC Online website recorded an all time

Internet

The BBC's online presence includes a comprehensive

The centre of the website is the Homepage, which features a modular layout. Users can choose which modules, and which information, is displayed on their homepage, allowing the user to customise it. This system was first launched in December 2007, becoming permanent in February 2008, and has undergone a few aesthetical changes since then.

Another large part of the site also allows users to watch and listen to most Television and Radio output live and for seven days after broadcast using the

The BBC has often included learning as part of its online service, running services such as BBC Jam, Learning Zone Class Clips and also runs services such as BBC WebWise and First Click which are designed to teach people how to use the internet. BBC Jam was a free online service, delivered through broadband and narrowband connections, providing high-quality interactive resources designed to stimulate learning at home and at school. Initial content was made available in January 2006; however, BBC Jam was suspended on 20 March 2007 due to allegations made to the European Commission that it was damaging the interests of the commercial sector of the industry.[185]

In recent years, some major on-line companies and politicians have complained that BBC Online receives too much funding from the television licence, meaning that other websites are unable to compete with the vast amount of advertising-free on-line content available on BBC Online.[186] Some have proposed that the amount of licence fee money spent on BBC Online should be reduced—either being replaced with funding from advertisements or subscriptions, or a reduction in the amount of content available on the site.[187] In response to this the BBC carried out an investigation, and has now set in motion a plan to change the way it provides its online services. BBC Online will now attempt to fill in gaps in the market, and will guide users to other websites for currently existing market provision. (For example, instead of providing local events information and timetables, users will be guided to outside websites already providing that information.) Part of this plan included the BBC closing some of its websites, and rediverting money to redevelop other parts.[188][189]

On 26 February 2010,

Interactive television

BBC Red Button is the brand name for the BBC's

Music

The BBC employs 5 staff orchestras, a professional choir, and supports two amateur choruses, based in BBC venues across the UK;

The

Many famous musicians of every genre have played at the BBC, such as

Other

The BBC operates other ventures in addition to their broadcasting arm. In addition to broadcasting output on television and radio, some programmes are also displayed on the

In 1951, in conjunction with Oxford University Press the BBC published The BBC Hymn Book which was intended to be used by radio listeners to follow hymns being broadcast. The book was published both with and without music, the music edition being entitled The BBC Hymn Book with Music.[198] The book contained 542 popular hymns.

Ceefax

The BBC provided the world's first teletext service called Ceefax (near-homophonous with "See Facts") from 23 September 1974 until 23 October 2012 on the BBC1 analogue channel, then later on BBC2. It showed informational pages, such as News, Sport, and the Weather. From New Year's Eve, 1974, ITV's

BritBox

In 2016 the BBC, in partnership with fellow UK broadcasters ITV and Channel 4 (who later withdrew from the project), set up 'project kangaroo' to develop an international online streaming service to rival services such as Netflix and Hulu.[200][201] During the development stages 'Britflix' was touted as a potential name. However, the service eventually launched as BritBox in March 2017. The online platform shows a catalogue of classic BBC and ITV shows, as well as making a number of programmes available shortly after their UK broadcast. As of 2021[update], BritBox is available in the UK, the US, Canada, Australia, and, more recently, South Africa, with the potential availability for new markets in the future.[200][202][203][204][205]

Commercial activities

BBC Studios (formerly BBC Worldwide) is the wholly owned commercial subsidiary of the BBC, responsible for the commercial exploitation of BBC programmes and other properties, including a number of television stations throughout the world. It was formed following the restructuring of its predecessor, BBC Enterprises, in 1995. Prior to this, the selling of BBC television programmes was at first handled in 1958 with the establishment of a business manager post.[206] This gradually expanded until the establishment of the Television Promotions (later renamed Television Enterprises) department in 1960 under a general manager.[206]

The company owns and administers a number of commercial stations around the world operating in a number of territories and on a number of different platforms. The channel

BBC Studios also distributes the 24-hour international news channel

In addition to these channels, many BBC programmes are sold via BBC Studios to foreign television stations with comedy, documentaries, crime dramas (such as

In addition to programming, BBC Studios produces material to accompany programmes. The company maintained the publishing arm of the BBC,

BBC Studios also publishes books, to accompany programmes such as

Cultural significance

Until the development, popularisation, and domination of television, radio was the broadcast medium upon which people in the United Kingdom relied. It "reached into every home in the land, and simultaneously united the nation, an important factor during the Second World War".

Despite the advent of commercial television and radio, with competition from ITV, Channel 4 and

The British Academy Film Awards (BAFTAs) was first broadcast on the BBC in 1956, with Vivien Leigh as the host.[224] The television equivalent, the British Academy Television Awards, has been screened exclusively on the BBC since a 2007 awards ceremony that included wins for Jim Broadbent (Best actor) and Ricky Gervais (Best comedy performance).[225]

The term "BBC English" was used as an alternative name for

Colloquial terms

Older domestic UK audiences often refer to the BBC as "the Beeb", a nickname originally coined by Peter Sellers on The Goon Show in the 1950s, when he referred to the "Beeb Beeb Ceeb". It was then borrowed, shortened and popularised by radio DJ Kenny Everett.[229] David Bowie's recording sessions at the BBC were released as Bowie at the Beeb, while Queen's recording sessions with the BBC were released as At the Beeb.[230] Another nickname, now less commonly used, is "Auntie", said to originate from the old-fashioned "Auntie knows best" attitude, or the idea of aunties and uncles who are present in the background of one's life (but possibly a reference to the "aunties" and "uncles" who presented children's programmes in the early days)[231] in the days when John Reith, the BBC's first director general, was in charge. The term "Auntie" for the BBC is often credited to radio disc-jockey Jack Jackson.[17] To celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of the BBC the song "Auntie" was released in 1972.[232] The two nicknames have also been used together as "Auntie Beeb".[233]

Logo and symbols

Logos

-

BBC's first three-box logo used from 1958 until 1963[234]

-

BBC's second three-box logo used from 1963 until 1971[235]

-

BBC's third three-box logo used from 1971 until 1988[235]

-

BBC's fourth three-box logo used from 1988 until 1998[236]

-

BBC's sixth and current three-box logo used since 2021[237]

Coat of arms

|

|

Controversies

Throughout its existence, the BBC has faced numerous accusations regarding many topics: the

The BBC has long faced accusations of

Conversely, writing for

Paul Mason, a former Economics Editor of the BBC's Newsnight programme, criticised the BBC as "unionist" in relation to its coverage of the Scottish independence referendum campaign and said its senior employees tended to be of a "neo-liberal" point of view.[252] The BBC has also been characterised as a pro-monarchist institution.[253] The BBC was accused of propaganda by conservative journalist and author Toby Young due to what he believed to be an anti-Brexit approach, which included a day of live programming on migration.[254]

In 2008, the BBC was criticised by some for referring to the men who carried out the

A BBC World Service newsreader who presented a daily show produced for

In February 2021, following Ofcom's decision to cancel the licence of China Global Television Network (CGTN) and the BBC's coverage of the persecution of ethnic minority Uighurs in China, the Chinese authorities banned BBC World News from broadcasting in the country. According to a statement from China's National Radio and Television Administration (NRTA), BBC World News reports on China "infringed the principles of truthfulness and impartiality in journalism" and also "harmed China's national interests".[270] Radio Television Hong Kong (RTHK) suspended BBC World News the day after the ban took effect on the mainland.[271]

In 2023, the BBC's offices in New Delhi were searched by officials from the Income Tax Department. The move came after the BBC released a documentary on Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi. The documentary investigated Modi's role in the 2002 Gujarat riots, which resulted in more than 1,000 deaths. The Indian Government banned viewing of the documentary in India and restricted clips of the documentary on social media.[272] While the BBC accused the Modi government of press intimidation by referring to reports of various organisations such as Amnesty International and Reporters Without Border, in June 2023, the BBC acknowledged that they had underpaid tax liabilities in India.[273][274][275]

See also

- Gaelic broadcasting in Scotland

- The Green Book (BBC)

- List of BBC television channels and radio stations

- List of companies based in London

- List of television programmes broadcast by the BBC

- List of BBC podcasts

- Prewar television stations

- Public service broadcasting in the United Kingdom

- Quango

- Television in the United Kingdom

- All pages with titles beginning with BBC

Notes

- ^ As of 2023, the State Media Monitor, considers the BBC as "Independent Public" broadcaster,[1] the highest level of independence given among a ranking of state media.[2]

- ^ The BBC itself wrote on the matter (in about 2005) that it can not "express its own editorial opinion about current affairs or matters of public policy", and that that "is not to say, of course, that controversial programmes are never broadcast, but great care is taken to ensure that arguments are well balanced."[110]

- ^ BBC Three originally ceased broadcasting as a linear television channel in February 2016 and returned to television in February 2022

References

- ^ "British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) – State Media Monitor". State Media Monitor – The world's state and public media database. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

- ^ "Typology – State Media Monitor". State Media Monitor – The world's state and public media database. Retrieved 6 April 2024.: The State Media Monitor differentiates between 7 different degrees of state media outlets: 1. Independent Public Media; 2.Independent State Managed/Owned Media; 3. Independent State Funded Media; 4. Independent State Funded and State Managed/Owned Media; 5. Captured Private Media; 6. Captured Public or State Managed/Owned Media; 7. State Controlled Media

- ^ a b c d e f "BBC Group Annual Report and Accounts 2021/22" (PDF). BBC. 6 July 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 July 2021. Retrieved 5 September 2022.

- ^ "BBC History – The BBC takes to the Airwaves". BBC News. Archived from the original on 6 March 2007. Retrieved 19 July 2007.

- ^ "BBC: World's largest broadcaster & Most trusted media brand". Media Newsline. 13 August 2009. Archived from the original on 5 October 2010. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- ^ Lloyd, John (4 July 2009). "Digital licence". Prospect. Archived from the original on 7 November 2011. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- ^ "About the BBC – What is the BBC". BBC. Archived from the original on 16 January 2010. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- ISBN 978-0-7619-4393-8.

- ^ "BBC – Governance – Annual Report 2013/14". BBC. Archived from the original on 5 July 2019. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- ^ "BBC Annual Report & Accounts 2008/9: Financial Performance". BBC. Archived from the original on 10 February 2010. Retrieved 12 February 2010.

- ^ "Legislation and policy". TV Licensing. Archived from the original on 29 January 2010. Retrieved 12 February 2010.

- ^ "TV Licence Fee: facts & figures" (Press release). BBC Press Office. April 2010. Archived from the original on 7 September 2010. Retrieved 12 February 2010.

- ^ Williams, Christopher (20 December 2016). "BBC Studios wins go-ahead for commercial production push". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022.

- ^ "BBC Global News Ltd to Be Everywhere" (Press release). BBC Media Centre. June 2015. Archived from the original on 19 October 2023. Retrieved 18 October 2023.

- ^ Shearman, Sarah (21 April 2009). "BBC Worldwide wins Queen's Enterprise award". MediaWeek. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 27 June 2019.

- ^ Potter, Simon J. (2022). This Is the BBC Entertaining the Nation, Speaking for Britain, 1922–2022. Oxford University Press.

the significant impact that the BBC has had on the social and cultural history of Britain

- ^ a b "Jack Jackson: Rhythm And Radio Fun Remembered" (Press release). BBC Media Centre. February 2017. Archived from the original on 26 June 2019. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- ^ "Top of the Pops 2 – Top 5". BBC. Archived from the original on 26 June 2019. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- ^ a b c d Briggs 1985.

- ^ a b c d e Curran & Seaton 2018.

- ^ "BBC 100: 1920s". BBC. Archived from the original on 18 October 2022. Retrieved 18 October 2022.

- ISBN 9780521661171. Archivedfrom the original on 11 August 2014. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ISBN 978-0-333-19720-2.

- ^ "No need to change BBC's mission to 'inform, educate and entertain'". UK Parliament. 24 February 2016. Archived from the original on 31 October 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- ^ a b c "BBC history, profile and history". CompaniesHistory.com. Archived from the original on 18 May 2022. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ Higgins, Charlotte (18 August 2014). "BBC's long struggle to present the facts without fear or favour". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 18 December 2022. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ Crook, Tim (2002). "International Radio Journalism". Routledge.

- ^ "The Man with the Flower in his Mouth". BBC. 9 October 2017. Archived from the original on 21 October 2018. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- ^ "BBC's first television outside broadcast" (PDF). Prospero. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2017. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ISBN 9780199208951. Retrieved 11 February 2010.

- Charles Mowat, Britain between the Wars 1918–1940 (1955) p 242.

- ^ David Hendy, "Painting with Sound: The Kaleidoscopic World of Lance Sieveking, a British Radio Modernist," Twentieth Century British History (2013) 24#2 pp 169–200.

- ^ Mike Huggins, "BBC Radio and Sport 1922–39," Contemporary British History (2007) 21#4 pp 491–515.

- ISBN 9780719079443.

- ^ ISBN 9780754655176.

- from the original on 22 December 2020. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- ISBN 978-0521661171.

- ^ ISBN 978-0631175438.

- ^ ISBN 978-0715621820.

- ^ ISBN 9780199568963.

- ^ "1920s". bbc.com. Archived from the original on 16 May 2020. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- ^ "Sir Isaac Shoenberg, British inventor". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 22 July 2021.

principal inventor of the first high-definition television system

- ISBN 978-0-563-20102-1.

- ^ BBC Hand Book (1929), pp. 164, 182, 186

- ^ "National Programme Daventry, 31 October 1938 20.10: Farewell to Reginald Foort". Radio Times. 61 (787). BBC. 28 October 1938. Archived from the original on 4 October 2021. Retrieved 11 September 2021.

- ^ "Orwell statue unveiled". About the BBC. 7 November 2017. Archived from the original on 19 November 2017. Retrieved 2 December 2017.

- ^ Christopher H. Sterling (2004). "Encyclopedia of Radio 3-Volume Set". p. 524. Routledge

- ^ "How de Gaulle speech changed fate of France". BBC. 4 January 2018. Archived from the original on 31 August 2017. Retrieved 4 January 2018.

- ^ "Children's Hour: Princess Elizabeth", BBC Archive, 13 October 1940, archived from the original on 27 November 2019, retrieved 17 September 2022

- ^ ISBN 978-0719046087.

- ^ ISBN 978-0195111507.

- ^ ISBN 9780773414877.

- .

- S2CID 192078695.

- ISBN 9781474413596.

- ^ Leigh, David; Lashmar, Paul (18 August 1985). "The Blacklist in Room 105. Revealed: How MI5 vets BBC staff". The Observer. p. 9. Archived from the original on 13 May 2019. Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- ^ Mark Hollingsworth and Richard Norton-Taylor Blacklist: The Inside Story of Political Vetting, London: Hogarth, 1988, p. 103. The relevant extract from the book is here Archived 4 October 2002 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sargeant, Paul (2010), Looking Back at the BBC, London: BBC, archived from the original on 22 December 2020, retrieved 9 November 2010

- ^ Graham, Russ J. (31 October 2005). "Baird: The edit that rewrote history". Archived from the original on 18 July 2006. Retrieved 11 August 2006.

- ^ "BBC Annual Report and Handbook". p. 215. BBC 1985

- ^ "Committees of Enquiry: Pilkington Committee" (PDF). 1 June 1962. p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 October 2006. Retrieved 30 September 2006.

- ^ Carter, Imogen (27 September 2007). "The day we woke up to pop music on Radio 1". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 18 October 2007. Retrieved 30 September 2007.

- ^ Partridge, Rob (13 November 1971). "Radio in London". Billboard. Archived from the original on 25 January 2016. Retrieved 2 August 2010.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-215964-9.

- ^ The Guestroom for Mr Cock-up Archived 24 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine Pick of the Continuity Announcers, 6 April 2000

- ^ Ratings for 1978 Archived 27 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine Independent Teleweb

- ^ McDonald, Sarah. "15 October 2004 Sarah McDonald, Curator Page 1 10/15/04 Hulton|Archive – History in Pictures" (PDF). Getty Images. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 May 2013. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- ^ Guider, Elizabeth (22 July 1987). "New BBC Management Team Sees Radio, TV Divisions Joining Forces". Variety. p. 52.

- ^ Holmwood, Leigh (15 August 2007). "BBC Resources sell-off to begin". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- ^ "New children's channels from BBC launch". Digital Spy. 11 February 2002. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ "Inside the BBC: BBC Radio stations". www.bbc.co.uk. BBC. Archived from the original on 10 January 2019. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ a b "BBC to launch new commercial subsidiary following DCMS approval" (Press release). BBC Press Office. 23 January 2002. Archived from the original on 22 October 2023. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- ^ "BBC Broadcast sell-off approved". BBC News. 22 July 2005. Archived from the original on 13 March 2022. Retrieved 11 December 2008.

- ^ a b "BBC announces Siemens Business Services as Single Preferred Bidder" (Press release). BBC Press Office. Archived from the original on 16 December 2021. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- ^ a b "New firm to support BBC IT". Ariel. BBC. 4 July 2011. Archived from the original on 3 July 2013. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- ^ "The Random House Group acquires majority shareholding in BBC Books" (Press release). BBC Press Office. 22 June 2006. Archived from the original on 23 November 2018. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- ^ "BBC announces successful bidder for BBC Outside Broadcasts" (Press release). BBC Press Office. 7 March 2008. Archived from the original on 22 October 2023. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- ^ "New home for BBC costume archive". BBC News. 30 March 2008. Archived from the original on 6 December 2008. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- ^ Sweney, Mark (16 August 2011). "BBC Worldwide agrees £121m magazine sell-off". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- ^ Wells, Matt (11 January 2007). "Dyke departure minutes released". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 4 December 2013. Retrieved 22 March 2010.

- ^ Lyall, Sarah (24 May 2005). "BBC Employees Stage 24-Hour Strike to Protest Planned Job Cuts". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 4 November 2022. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ "BBC strike hits TV, radio output". CNN. 23 May 2005. Archived from the original on 4 November 2022. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ "Radical reform to deliver a more focused BBC" (Press release). BBC Press Office. 18 October 2007. Archived from the original on 20 October 2007. Retrieved 18 October 2007.

- ^ "Television licence fee to be frozen for the next six years". BBC News. 20 October 2010. Archived from the original on 7 October 2011. Retrieved 6 October 2011.

- ^ "BBC set to cut 2000 jobs by 2017". BBC News. 6 October 2011. Archived from the original on 6 October 2011. Retrieved 6 October 2011.

- ^ "BBC cuts at a glance". BBC News. 6 October 2011. Archived from the original on 6 October 2011. Retrieved 6 October 2011.

- ^ "BBC cuts: in detail". The Daily Telegraph. London. 6 October 2011. Archived from the original on 6 October 2011. Retrieved 6 October 2011.

- ^ "BBC1 to go live for coronation anniversary night in 2013". The Guardian. London. 21 September 2010. Archived from the original on 4 December 2017.

- ^ Goodacre, Kate (26 November 2015). "BBC Three will move online in March 2016 as BBC Trust approves plans to axe broadcast TV channel". Digital Spy. Archived from the original on 29 December 2015. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- ^ "BBC Three reveals new logo and switchover date". BBC News. 4 January 2016. Archived from the original on 4 January 2016. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- ^ "BBC making £34m investment in children's services". BBC News. 4 July 2017. Archived from the original on 7 July 2017. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- ^ Ruddick, Graham (4 July 2017). "BBC promises a wider mix than rivals as it seeks to reinvent itself". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 7 July 2017. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- ^ Linford, Paul. "Local Democracy Reporting service 'has become template" says Davie – Journalism News from HoldtheFrontPage". Hold the Front Page. Archived from the original on 11 August 2022. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ Martinson, Jane (8 March 2016). "BBC increases savings target to £800m a year to pay for drama and sport". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 6 January 2021. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- ^ Midgley, Neil (11 May 2016). "£800 Million Of BBC Cuts Already Needed? Not Quite, Tony Hall". Forbes. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- ^ Mar, Leon (7 September 2019). "CBC/Radio-Canada joins global charter to fight disinformation". CBC/Radio-Canada. Archived from the original on 11 August 2023. Retrieved 15 October 2023.

- ^ "New collaboration steps up fight against disinformation". BBC. 7 September 2019. Archived from the original on 15 October 2023. Retrieved 15 October 2023.

- ^ "BBC News to close 450 posts as part of £80m savings drive". BBC News. 29 January 2020. Archived from the original on 15 December 2020. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ Waterson, Jim (15 July 2020). "BBC announces further 70 job cuts in news division". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- ^ Barker, Alex (15 September 2020). "BBC faces era of cuts after reporting 'substantial shortfall'". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 15 January 2021. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- ^ "Former banker Richard Sharp to be next BBC chairman". BBC News. 6 January 2021. Archived from the original on 30 April 2023. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- ^ "Labour vows to 'secure BBC's independence' after Lineker row". The Guardian. 26 March 2023. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- ^ "Richard Sharp resigns as BBC chairman after Boris Johnson £800,000 loan row". Sky News. Archived from the original on 28 April 2023. Retrieved 28 April 2023.

- ^ Wilkinson, Peter (28 April 2023). "BBC chairman resigns after controversy involving loan deal for former PM Boris Johnson | CNN Business". CNN. Archived from the original on 28 April 2023. Retrieved 28 April 2023.

- ^ "Dame Elan Closs Stephens appointed acting BBC chairwoman". BBC News. 2 June 2023. Archived from the original on 19 June 2023. Retrieved 13 August 2023.

- ^ a b "Dr Samir Shah CBE". BBC.com. Retrieved 4 March 2024.

- ^ "BBC regulation". Ofcom. 29 March 2017. Archived from the original on 29 April 2017. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ^ "BBC Board Appointments". BBC Media Centre. 23 March 2017. Archived from the original on 21 August 2019. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- ^ a b "Charter and Agreement".

- ^ "The BBC on funding, and the charter". BBC World Service.

- ^ "ECopy of Royal Charter for the continuance of the British Broadcasting Corporation" (PDF). BBC. December 2016. Retrieved 16 February 2024.

- ^ "BBC World Service – Institutional – How is the World Service funded?". BBC World Service. Archived from the original on 8 October 2012. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

The BBC, including World Service, operates under two constitutional documents – its Royal Charter and the Licence and Agreement. The Charter gives the Corporation legal existence, sets out its objectives and constitution, and also deals with such matters as advisory bodies. Under the Royal Charter, the BBC must obtain a licence from the Home Secretary. The Licence, which is coupled with an Agreement between the Minister and the Corporation, lays down the terms and conditions under which the BBC is allowed to broadcast.

- ^ "Who we are". About the BBC. 1 April 2019. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- ^ "Board Appointment". BBC Media Centre. 23 March 2017. Archived from the original on 21 August 2019. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- ^ "Dame Elan Closs Stephens appointed acting BBC chairwoman". BBC News. 2 June 2023. Archived from the original on 2 June 2023. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ "Meeting of the BBC Board – Minutes – 8 December 2022" (PDF). BBC. p. 6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 April 2023. Retrieved 28 April 2023.

- ^ "Executive committee". About the BBC. Archived from the original on 22 December 2020. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- ^ "Charlotte Moore appointed to BBC Board". BBC Media Centre. 3 September 2020. Archived from the original on 9 April 2021. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- ^ "BBC Radio and Education moves to new division". Radio Today. Archived from the original on 25 June 2022. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ bbc.co.uk About The BBC section Archived 15 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 9 July 2011

- ^ a b c d e f g h "The vetting files: How the BBC kept out 'subversives'". BBC News. 22 April 2018. Archived from the original on 22 April 2018. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

- ^ Hastings, Chris (2 July 2006). "Revealed: how the BBC used MI5 to vet thousands of staff". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 26 April 2018. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

- ^ "The Blacklist in Room 105". The Observer. London. 18 August 1985. Archived from the original on 13 May 2019. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

- ^ "BBC Full Financial Statements 2013/14" (PDF). BBC Annual Report and Accounts 2013/14. BBC. July 2014. p. 20. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 November 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- ^ "Annual Report 2014" (PDF). British Sky Broadcasting. July 2014. p. 86. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 March 2015. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- ^ "ITV plc Annual Report and Accounts for the year ended 31 December 2013" (PDF). ITV. 2014. p. 109. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 June 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- ^ "How much does a TV Licence cost? – TV Licensing ™". www.tvlicensing.co.uk. Archived from the original on 17 July 2019. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- ^ "Blind/severely sight impaired". TV Licensing. 1 April 2000. Archived from the original on 22 November 2011. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

- ^ "Important information about over 75 TV Licences". TV Licensing. Archived from the original on 23 September 2020. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ "Further Issues for BBC Charter Review" (PDF). House of Lords Session Report. The Stationery Office Limited. 3 March 2006. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 March 2009. Retrieved 15 August 2008.

- ^ "Key Facts, The TV Licence Fee". BBC Web Site. BBC Press Office. April 2008. Archived from the original on 8 July 2007. Retrieved 31 July 2008.

- ^ "BBC response to Freedom of Information request – RFI 2006000476" (PDF). bbc.co.uk/foi. 25 August 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 April 2008.

- ^ "TV Licensing Annual Review 2018/19". Tvlicensing.co.uk. Archived from the original on 30 July 2019. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ "BBC: TV licence fee decriminalisation being considered". BBC News. 15 December 2019. Archived from the original on 21 December 2020. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ BBC. "Annual Report and Accounts 2004–2005" (PDF). p. 94. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

- ^ a b "BBC Annual Report 2018/19" (PDF). BBC. July 2019. p. 133; 91. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 July 2019. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ Heffer, Simon (22 September 2006). "Why am I being hounded like this?". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 17 November 2007. Retrieved 6 February 2008.

- ^ Johnson, Boris (26 May 2005). "I won't pay to be abused by the BBC". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 15 August 2007. Retrieved 6 February 2008.

- ^ "BBC bullies' shame in licence fee chaos". Daily Express. London. 7 November 2007. Archived from the original on 24 July 2012. Retrieved 6 February 2008.

- TV Licensing. 2 June 2008. Archivedfrom the original on 7 February 2008. Retrieved 6 February 2008.

- ^ "Example of Licence Fee pressure group". Campaign to Abolish the Licence Fee. 2 June 2008. Archived from the original on 20 February 2008. Retrieved 6 February 2008.

- ^ "Annual Review 2012/13" (PDF). BBC Worldwide. p. 34. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 August 2013. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ "BBC Broadcasting House extension – review". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 11 May 2019. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- ^ "BBC Television Centre closes its doors for the last time". The Evening Standard. 31 March 2013. Archived from the original on 25 January 2016. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- ^ BBC. "New Broadcasting House – The future". Archived from the original on 21 May 2006. Retrieved 6 July 2006.

- ^ BBC. "BBC News' television output moves to new studios at Broadcasting House". Archived from the original on 5 May 2019. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- ^ BBC. "New Broadcasting House". Archived from the original on 5 October 2009. Retrieved 16 September 2009.

- ^ "BBC Television Centre up for sale". BBC News. 13 June 2011. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 11 July 2011.

- ^ BBC News Online (31 May 2007). "BBC Salford move gets green light". Archived from the original on 31 August 2007. Retrieved 31 May 2007.

- ^ "BBC North". BBC. Archived from the original on 20 June 2011. Retrieved 11 July 2011.

- ^ "Roath Lock studios". Roathlock.com. Archived from the original on 1 April 2012. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ "Atos Origin acquires Siemens division for €850m". Computer Weekly. 15 December 2010. Archived from the original on 12 May 2013. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- ^ "Atos signs new contract with BBC for technology services". Atos. 11 May 2017. Archived from the original on 19 September 2020. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- ^ "BBC Effiicency Programme". House of Commons Public Accounts Committee. UK Parliament. 21 November 2011. Archived from the original on 5 February 2013. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- ^ Mari, Angelica (26 January 2012). "CIO interview: John Linwood, chief technology officer, BBC". Computer Weekly. Archived from the original on 28 May 2013. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- ^ "BBC publishes Annual Report for 2011/12". BBC Trust. 16 July 2012. Archived from the original on 21 December 2012. Retrieved 21 September 2012.

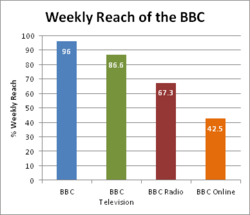

- ^ a b c "Part 2 – The BBC Executive's Review and Assessment" (PDF). Annual Report 2011–12. London, United Kingdom: BBC. 16 July 2012. pp. 4–9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 October 2012. Retrieved 21 September 2012.

- ^ "BBC Three returns to TV with RuPaul special and regional focus". 1 February 2022. Archived from the original on 19 March 2022. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- ^ "BBC News Report". 15 March 2007. Archived from the original on 17 March 2007. Retrieved 15 March 2007.

- ^ "BBC Annual Report 2011-12 reach pages". Archived from the original on 21 December 2012. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- ^ "BBC Alba Freeview date unveiled". BBC News. 23 May 2011. Archived from the original on 26 May 2011. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- ^ "BBC Press Release: BBC to trial High Definition broadcasts in 2006". 8 November 2005. Archived from the original on 18 May 2006. Retrieved 7 July 2006.

- ^ "BBC Scotland – BBC Scotland – Welcome to your brand new television channel: BBC Scotland". BBC. Archived from the original on 7 November 2020. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ Aerial warfare Archived 9 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine, John Waters, The Independent, 21 April 1997

- ^ "BBC One and BBC Two to be simulcast from 27 November". BBC. 19 November 2008. Archived from the original on 25 August 2011. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

- ^ "BBC Three to be axed as on-air channel". BBC News. 5 March 2014. Archived from the original on 5 March 2014. Retrieved 5 March 2014.

- ^ a b c Kelion, Leo (7 December 2012). "BBC finishes Radio Times archive digitisation effort". BBC Online. Archived from the original on 9 February 2013. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- ^ BBC Archive Development (15 October 2014). "Genome – Radio Times archive now live". BBC Online. Archived from the original on 29 December 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- ^ "TV licence fee not value for money – inquiry hears". IOM Today. Douglas. 8 February 2011. Archived from the original on 21 December 2012. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- ^ "192 Million BBC World Service Listeners". BBC World Service. 25 October 2015. Archived from the original on 1 August 2013. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- ^ "BBC World Service Annual Review 2009–2010" (PDF). Annual Review. BBC World Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- ^ "How BBC World Service is run". BBC. Archived from the original on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- ^ Harkey, Clare (13 March 2006). "BBC Thai service ends broadcasts". BBC News. Archived from the original on 18 December 2008. Retrieved 8 November 2008.

- Middle East Times. Sydney. 15 March 2006. Archived from the originalon 30 October 2006. Retrieved 6 July 2006.

- ^ Corke, Stuart (25 October 2012). "MediaTel information for all BBC and commercial radio stations". Mediatel.co.uk. Archived from the original on 21 December 2012. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- ^ The Radio Academy "Patrons" Archived 7 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "This is BBC News". About BBC News. BBC. 13 September 2006. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- ^ Cozens, Claire (8 July 2005). "BBC news ratings double". The Guardian. UK. Archived from the original on 10 July 2012. Retrieved 25 December 2006.

- ^ BBC. "Statistics on BBC Webservers 7 July 2005". Archived from the original on 12 October 2006. Retrieved 13 November 2006.

- ^ "BBC keeps web adverts on agenda". BBC News. 22 February 2007. Archived from the original on 15 January 2009. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

- ^ "bbc.co.uk Commissioning". Archived from the original on 6 July 2006. Retrieved 6 July 2006.

- ^ "bbc.co.uk Key Facts". Archived from the original on 24 May 2006. Retrieved 6 July 2006.

- ^ Titus, Richard (13 December 2007). "A lick of paint for the BBC homepage". BBC Internet Blog. Archived from the original on 5 February 2008. Retrieved 5 February 2008.

- ^ "BBC News opens its archives for the first time" (Press release). BBC Press Office. 3 January 2006. Archived from the original on 22 October 2023. Retrieved 3 October 2006.

- ^ "BBC Trust suspends BBC Jam" (Press release). BBC Trust. 14 March 2007. Archived from the original on 26 January 2008. Retrieved 5 February 2008.

- ^ Graf, Philip. "Department of Culture, Media and Sport: Independent Review of BBC Online, pp41-58" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 July 2006. Retrieved 6 July 2006.

- ^ British Internet Publishers Alliance (31 May 2005). "BIPA Response to Review of the BBC's Royal Charter". Archived from the original on 27 August 2006. Retrieved 6 July 2006.

- ^ "Public value key to BBC websites". BBC News. 8 November 2004. Archived from the original on 16 June 2006. Retrieved 6 July 2006.

- ^ Burrell, Ian (14 August 2006). "99 per cent of the BBC archives is on the shelves. We ought to liberate it". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 6 July 2008. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- ^ Foster, Patrick (26 February 2010). "BBC signals an end to era of expansion". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 23 April 2010. Retrieved 26 February 2010.

- ^ "BBC Proposes Deep Cuts in Web Site". The New York Times. 3 March 2010. Archived from the original on 23 April 2017. Retrieved 2 March 2010.

- ^ "BBC 6 Music and Asian Network face axe in shake-up". BBC News. 2 March 2010. Archived from the original on 3 March 2010. Retrieved 2 March 2010.

- ^ "Press Office – First look at new animated Doctor Who". BBC. Archived from the original on 20 November 2021. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- ^ "BBC Orchestras and Choirs". BBC Music Events. Archived from the original on 14 October 2019. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- ^ "BBC Radio 3 – BBC Proms – History of the Proms". BBC. Archived from the original on 14 April 2019. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- ^ "BBC – BBC orchestras and choirs – Media Centre". www.bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 23 December 2020. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- ^ "BBC One Celebrates 60 Years of the Eurovision Song Contest with special anniversary event". BBC. Archived from the original on 1 January 2022. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ British Broadcasting Corporation (1969) The BBC Hymn Book with Music London: Oxford University Press

- ^ Griffin, Andrew (30 September 2020). "BBC red button: Corporation U-turns on plans to cut services". Independent. Archived from the original on 16 October 2020. Retrieved 21 October 2022.

- ^ a b "Britbox, a streaming service for British TV from the BBC and ITV, launches in the US". The Verge. 7 March 2017. Archived from the original on 28 December 2017. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ^ "BBC set to launch Britflix rival to Netflix after John Whittingdale approves subscription streaming". www.msn.com. Archived from the original on 9 June 2016. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- ^ "'Britflix' and chill – doesn't have the quite same ring to it". The Guardian. London. 16 May 2016. Archived from the original on 21 May 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- ^ "BBC and ITV set to launch Netflix rival". BBC News. 27 February 2019. Archived from the original on 26 July 2019. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- ^ "Britbox launches in Australia". Broadband TV News. 23 November 2020. Archived from the original on 23 November 2020. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- ^ "BritBox launched in South Africa at R100/month". TechCentral. 27 July 2021. Archived from the original on 27 July 2021. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ^ ISBN 0-563-36750-4.

- ^ "BBC's biggest bureau outside the UK is in Africa – Nairobi, Kenya". African News. Archived from the original on 24 May 2023. Retrieved 24 May 2023.

- ^ a b Henery, Michelle. "Why Do We See What We See: A comparison of CNN International, BBC World News and Al Jazeera English, analysing the respective drivers influencing editorial content" (PDF). reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, University of Oxford, 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 September 2016. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- ^ "Strictly Come Dancing: the worldwide phenomenon". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 25 August 2022.

- ^ "Dancing with the Stars advertising opportunities". Advertising.bbcworldwide.com. Archived from the original on 15 September 2012. Retrieved 20 September 2012.

- ISBN 978-1903053096.

- ^ "The Radio Times". BBC. Archived from the original on 9 August 2022. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- ISBN 978-1-85793-441-0.

- ^ a b Perry (1999) p16

- ^ "URY History". Archived from the original on 6 October 2008. Retrieved 21 November 2008.

- ^ "Directory of Production Companies". The International Association of Wildlife Filmmakers. Archived from the original on 29 August 2010. Retrieved 6 July 2007.

- ^ Muir, Hugh (8 October 2008). "Public service broadcasting is 'lynchpin' of British culture, says Joan Bakewell". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 25 June 2010.

- Press Association. 12 May 2016. Archivedfrom the original on 31 October 2016. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- ^ "The BFI TV 100: 1–100". British Film Institute. 2000. Archived from the original on 23 February 2007. Retrieved 23 February 2007.

- ^ "BBC says fond farewell to Top of the Pops" (Press release). BBC Press Office. 20 June 2006. Archived from the original on 24 September 2020. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

- ^ "BBC's Match of the Day marks 50 years as an institution of English football". The Guardian. London. 16 August 2014. Archived from the original on 12 November 2021. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ Nikkhah, Roya (9 September 2012). "Great British Bake Off sees sales of baking goods soar". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 22 July 2019. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- ^ "Panorama returns to peak time on BBC ONE". BBC. Archived from the original on 29 June 2022. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- ^ "Switched On: Television joins the fold". BAFTA.org. Archived from the original on 6 January 2022. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- ^ "Bafta TV Awards 2007: The winners". BBC. Archived from the original on 23 January 2009. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- ^ Roach, Peter (2011). English Pronouncing Dictionary, 18th edition. Cambridge University Press. p. vi. Archived from the original on 20 January 2013. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ^ "Speaking out for regional accents". BBC News. 3 March 1999. Archived from the original on 30 September 2009. Retrieved 26 January 2009.

- ^ "Diversity Policy". BBC. Archived from the original on 7 February 2009. Retrieved 26 January 2009.

- ^ Davies, Alan. "Radio Rewind: Kenny Everett". Radio Rewind. Archived from the original on 1 May 2007. Retrieved 10 May 2007.

- ^ "Queen: Album Guide". Rolling Stone. New York. n.d. Archived from the original on 27 April 2012. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- ^ "Mark Thompson celebrates the official opening of a new state-of-the art BBC building in Hull" (Press release). BBC Press Office. 21 October 2004. Archived from the original on 28 June 2006. Retrieved 6 July 2006.

- ISSN 0006-2510.

- ^ "Auntie Beeb suffers a relapse". The Times. London. 7 December 2004. Archived from the original on 14 August 2011. Retrieved 12 February 2007.

- ^ "BBC logo design evolution, dating back to the 1950s". Logo Design Love. 26 August 2008. Archived from the original on 26 June 2019. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- ^ a b Walker, Hayden. "BBC Corporate Logo". TV ARK. Archived from the original on 4 March 2012. Retrieved 20 November 2010.

- ^ a b "The BBC logo story". BBC. Archived from the original on 14 October 2013. Retrieved 27 September 2013.

- ^ a b Bright, Kerris (19 October 2021). "Modernising audience experience across the BBC". BBC Media Centre (Press release). Archived from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 19 October 2021.

- ^ ISBN 9780900455216.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link - ^ "BBC complaints framework" (PDF). downloads.bbc.co.uk. BBC Trust. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 January 2015. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- ^ "House of Commons – Future of the BBC – Culture, Media and Sport". Publications.parliament.uk. Archived from the original on 22 August 2017. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ^ Deech, Baroness (3 July 2015). "Out of the frying pan into the fire: the BBC to OFCOM". lordsoftheblog.net. Lords of the Blog. Archived from the original on 6 July 2015. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- ^ Halliday, Josh (10 October 2012). "BBC reporting scrutinised after accusations of liberal bias". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 August 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.